Abstract

Changes in technologies have affected all industries. The oil and gas industry has also experienced the effects of technologies through the introduction of ERP platforms. ERP systems promised to revolutionise the industry through the handling of core business processes and operations. The study aimed to show that adaptation of firms to imposed conformity of ERP platforms was a major challenge in the Nigeria oil and gas industry.

Past studies have revealed that major challenges resulted from poor re-engineering and implementation processes. In most cases, the oil and industry environment was dynamic, with complex operations across different geographical areas. ERP platforms presented opportunities for standardising all processes on a single platform. However, many firms did not realise ERP potentials. The study was a mixed-methods approach.

This was necessary for gathering both quantitative and qualitative data about imposed conformity and adaptation of the oil and gas industry in Nigeria to ERP platforms. Results indicated that imposed conformity, as firms strived to standardise their operations to meet ERP rigid requirements, was a major challenge in the Nigeria oil and gas industry. May firms failed during re-engineering and implementation processes. However, multinational firms in the oil and gas industry of Nigeria relied on single platforms from the major ERP system developers to overcome such challenges. They had adequate resources for planning and training end-users of their systems. On the other hand, local firms experienced bureaucratic processes, internal interference, inadequate supports, training, and resources for re-engineering and implementation.

These conditions often led to the failure of ERP modules, which they deployed to manage their core business operations. The study concluded that Nigeria oil and gas firms needed effective training, adequate resources, re-engineering outline, and implementation of the system. This would identify challenges to the effective adaptation to the system after implementation. Oil and gas firms in Nigeria face different challenges from different sources.

Nevertheless, from ERP implementation, re-engineering and managing imposed conformity, further studies are necessary to determine how the Nigeria oil and gas industry can manage challenges posed by ERP systems’ imposed conformity on business processes. Such studies can provide valuable information, which the industry needs in order to prepare it for future challenges and overcome such challenges in order to achieve the industry strategic objectives.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) presented a potential system for integrating the entire business areas of focus in a firm. It aimed at creating a consolidated database for organisational processes on a real-time basis for effective management of business processes and operations. This study explores the challenges of ERP imposed conformity among the oil and gas industry of Nigeria.

What is ERP?

The ERP is a software architecture platform, which enhances the flow of information in an organisation among operations, logistics, finance, and the human resources department (Hicks, 1997). This suggests that ERP is an enterprise-wide application. The ERP depends on a central database based on a computing technology, which has integrated components that interact with various applications in order to consolidate core business operations into a single system.

Users of ERP systems feed data into the system only once (Hicks, 1997). All systems rely on that same data for consistency, completeness, and commonness. For instance, when a sales representative enters an order for a product into the ERP system of the company, the respective departments can get information immediately. The department responsible for verifying the stock can then proceed. At the same time, the accounting department will also generate the customer’s invoice while the shipper prepares for subsequent delivery of the goods. Customers who can gain access to the ERP platform or have links to the platform can also track movements of their orders. Data remain the same in all departments.

The integrated ERP platform allows all departments to have consistency and visible activities. Data must remain consistent in the entire organisation. However, not many organisations have been able to achieve the full potential of ERP platforms. Therefore, any organisation that wants to attain the full potential of ERP applications must re-engineer most processes of their businesses in order to align such operations with processes integrated into ERP applications. This is a complex process, which many organisations fail to achieve. This results in imposed conformity as such firms struggle to adapt to ERP platforms and align them with their processes.

ERP platforms rely on client or server technology. This allows users to conduct applications like inventory management, accounting, and others by utilising data from a core and common database. The ERP platform shows a decentralised system of computing that relies on a single centralised database.

The aim of the research

While ERP systems have changed operations in the oil and gas industry across the world, some firms still face significant challenges during implementation and subsequent adaptation. The study aimed to show that the Nigeria oil and gas industry has experienced challenges from imposed conformity of ERP systems. ERP platforms impose rigid requirements to firms, which are not flexible enough for rapid changes from technologies. While imposed conformity aims at ensuring that oil and gas firms achieve the full potential ERP systems, imposed conformity affects the way in which these firms operate their business. As a result, challenges of effective adaptation of ERP systems hinder the realisation of ERP potentials in the Nigeria oil and gas industry.

The researcher noted that no study had evaluated the impacts of imposed conformity on the operations and processes of firms. Thus, the study results would be useful for informing the oil and gas industry of Nigeria on effective re-engineering strategies in order to meet the rigid requirements of ERP platforms and achieve systems’ full potential.

The objectives of the research

The study objective was to investigate how the Nigeria oil and gas industry has adapted to ERP platforms. The article focused on imposed conformity, and its impacts on the re-engineering of current practices fit within the ERP platforms and their rigid requirements. In addition, it also evaluated how Nigeria oil and gas industry chose the right ERP platforms to match their strategic business goals.

Research Questions

- Has the Nigeria oil and gas industry effectively re-engineered its current practices to fit within the ERP platform requirements?

- Do oil and gas firms of Nigeria choose the right ERP platform to match their strategic goals?

The organisation of the article

The introduction section provides an overview of the ERP system and its usages in the oil and gas industry. The literature review section provides insights into previous studies while methodology shows study design. The findings show study results. The conclusion provides a general remark about the study outcomes.

Literature Review

The study objective focuses on ERP systems, organisational re-engineering, implementation, and adaptation of ERP systems with the current organisational practices. It focuses on the Nigeria oil and gas industry. This section provides available studies in the field.

ERP Strategy

For many oil and gas firms, it could be premature to begin by evaluating the potential impacts of ERP systems without understanding or defining the overall ERP strategy. Oil and gas firms should begin by defining their current business practices and technological environments in which they operate. Nigel Montgomery and Denise Ganl note that firms must also define business goals and ERP operations (Montgomery and Ganl, 2010). This approach provides a clear roadmap for subsequent ERP activities.

In case an organisation cannot define its ERP strategy, then it may get assistance from consulting firms, which specialise in ERP implementation, re-engineering, and adaptation. The aim of the ERP strategy should be to facilitate the following aspects of business processes:

- Defining business and ERP strategic objectives on both short-term and long-term visions

- Assessing the current ERP practices and the available IT infrastructure

- Understanding current strategies and ERP environment against those of the best multinational oil and gas firms in Nigeria

- Assessing cost-benefit of the current systems

- Conducting ROI analysis for the new ERP system in various areas like customer service, supply chain management, accounting, financial, HR issues, and geospatial data management among others

- The understanding weakness of the system

- Developing an ERP evaluation model after implementation, re-engineering, and adaptation

Ultimately, oil and gas firms should aim at minimising ERP platform failure, risks, and increasing costs while developing effective utilisation of the system for the growth of firms.

ERP Platforms in the Oil and Gas Industry

Porter notes that information technology (IT) affects different industries in various ways (Porter, 1985). Therefore, generalisation on how IT affects organisations in a given way would be a mistake. ERP platforms have played significant standardisation roles in the oil and gas industry (Romero, Anderson, Banker and Menon, 2005). ERP platforms in the oil and gas industry have helped firms to consolidate their operations within the global arena, which has created a strategic advantage for such firms (Gulledge and Simon, 2005). In this regard, the adoption of ERP platforms among firms in the oil and gas industry is critical because poor adoption can lead to failure of the system.

Integrated and standardised systems allow firms to have consistent data across various units of the business (Sammon and Adam, 2005). Most oil and gas firms have several dispersed business units across the globe, wells, a complicated supply chain, and there is increased competition within the industry. Thus, ERP has been an effective tool for managing such complex business processes and operations. Patricia Hewlett of Exxon Mobil and other scholars have noted that standardisation in the industry has led to cost reduction, competitive advantage, and business flexibility, which facilitated quick rollout to new locations and workload control among different business departments (Mitchell, 2006; Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005).

Some oil and gas firms may lack current and accurate data on their assets. This situation may result in the delayed replacement of under-performing resources, or the company may replace such assets soon (Ifinedo and Nahar, 2006). On this note, the ERP platform can provide reliable data on conditions of both external and internal assets of the company (Ifinedo and Nahar, 2006). Senior executives can use such information to make informed decisions.

An ERP platform has several ERP applications (Gulledge and Simon, 2005). These applications are efficient software packages for every department of the organisation (logistics, finance, human resource, inventory movement, sales, and marketing, among others). Currently, ERP vendors provide specialised software packages for specific purposes in a given industry (Montgomery and Ganl, 2010). In the oil and gas industry, ERP applications can manage various operations like supply chain management, automated sales and marketing, and financial activities among others.

Implementation

Firms often consider ERP systems implementation to be a complex initiative (Chang, Cheung, Cheung, and Yeung, 2008; Xue, Liang, Boulton and Snyder, 2005). Successful implementation of ERP systems and subsequent adaptation of firms rely on several factors. These factors include system evaluation, the selected vendor, consultant, implementation approach, and execution of important elements for effective implementation (Chang et al., 2008). However, many firms have failed to implement the ERP system effectively, which has affected utilisation of the system and adaptation. This has been a source of concern for ERP developers, oil and gas firms, and academia.

Oil and gas firms should conduct gap analyses before embarking on re-engineering of their processes in order to conform to ERP systems (Gulledge, 2006). Firms must have defined ERP objectives. This facilitates re-engineering, implementation, and adaptation of employees to the system (Light, 2005). It is important to train employees before deployment of the system. In addition, all processes require documentation for later improvement.

This helps an organisation to identify areas, which need extra efforts and adjustments. Every stage of implementation requires testing for defects. The company should test how its identified features will perform once it deploys the system on a regular use (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005).

It is necessary for a firm to concentrate on technical features of the ERP system during re-engineering and implementation (Gulledge, 2006; Light, 2005). They provide guidance on the development of user manuals, change management approaches, and data conversion among other core requirements. Downstream firms lacked high standards of collaboration, which affected implementation and adaptation of ERP platforms.

ERP systems relied on data from various sources, which decision-makers used for undertaking critical decisions in the company (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005). Thus, oil and gas firms in Nigeria should management data effectively in order to ensure efficient adaptation with ERP systems. Data accuracy is critical for all firms with ERP systems. Obviously, many oil and gas firms fail to prepare their employees before implementing ERP systems (Dezdar and Sulaiman, 2009). During adaptation stages, employees must realise that re-engineering may result in job losses, changes in operations, processes, and responsibilities.

Planning ERP Implementation

Many CEOs have recognised that they cannot realise a proper success of ERP platforms without strategic planning of implementation processes (Khanna and Arneja, 2012). In this regard, they noted that strategic planning was critical during the initial stages of ERP implementation. It was important to gather “all requirements and select the best ERP option” (Ifinedo and Nahar, 2006). At this point, senior executives noted that it was fundamental to find out how ERP solutions would change their operations.

In order to avoid implementation failures, oil and gas firms should consider working with experts who understand operations within the oil and gas industry. Experts must understand the selected ERP platform, its implementation requirements and potential challenges for successful implementation (Kamhawi, 2007). This would ensure that oil and gas firm implement their ERP solutions on time and on the allocated budget.

Planning of ERPs implementation involves finding the right experts who would ensure successful implementation of the system (Kamhawi, 2007). This would allow the business to realise its ERP goals. ERP vendors must implement the system in a proper manner. In addition, they must also ensure that the technology would be able to change business processes and reduce complexities within the oil and gas industry (Frick and Schubert, 2009). Experts in ERP implementation would ensure that oil and gas firms leverage on various ERP modules in order to achieve the best ERP practices during usages (Worley and Chatha, 2005).

ERP implementation experts should be able to make organisations to understand ERP implementation parameters, troubleshooting, needs, and vital factors for ERP success (Khanna and Arneja, 2012). In addition, the implementation team must be able to understand how different ERP systems from various developers work to enhance value to oil and gas firms.

Instances of ERP systems failures date back to 1990s. Many firms have noted that ERP systems are the most expensive to implement in terms of resources required. Studies have indicated that a number of ERP systems implementation have experienced considerable challenges (Goldberg, 2000; Krasner, 2000). As a result, there are “high rates of ERP system failures” (Nazir, 2005). However, ERP systems, which survive, experience adaptation challenges. Organisations must re-engineer their usual operational practices in order to match ERP requirements.

ERP systems have experienced adaptation challenges, which lead to high rates of failure (Kamhawi, 2007). The major contributors to failures in ERP platforms are technical challenges and people problems (Botta-Genoulaz and Millet, 2006). There are several challenges, which may affect ERP systems during or after installation. Such challenges are behavioural, cultures of an organisation, and procedures among others (Nazir, 2005).

Successful implementation of an ERP system in any industry is imperative because costs and risks associated with failure cannot match investments put in the system. Thus, the failure of the system can cause financial challenges to any business. Moreover, failure to re-engineer organisational practices to meet ERP requirements can lead to low usages of the system (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005).

According to Markus and colleagues, ERP systems are flexible (Markus et al., 2000). This implies that users can adjust ERP systems in order to meet their processes during implementation. At the same time, end users can also influence the type of ERP they need during decision-making processes and developmental stages. Thus, several challenges, which result from the ERP system implementation, are mainly mismatch between firm’s practices and ERP requirements.

Nazir noted that several ERP platforms did not have specific features for particular issues in the oil and gas industry (Nazir, 2005). As a result, some firms often develop their own in-house systems to capture such features. During implementation of ERP platforms, firms should ensure that they capture the required features (Nazir, 2005). However, if they fail to do so, then the new platforms may fail because they lack core features of ERPs required in business operations.

Still, firms, which fail to conduct a thorough mapping of their ERP systems based on business needs, may experience complete failure of ERP systems (Martin and Cheung, 2005). This happens because such systems cannot capture core business needs. However, firms, which may rely on in-house team to develop specific features for ERP platforms, may need skilled employees, adequate time, and resources. Developing new applications are expensive. Besides, such applications require time for testing. Any poorly designed applications may result into failure of the entire project.

It could be difficult for the oil and gas industry to combine their traditional practices with new approaches based on ERP systems (Frick and Schubert, 2009). Traditional approaches lack ERP capabilities of handling data. Moreover, data conversions from legacy systems to new systems can present considerable difficulties for companies. Mapping during systems re-engineering may also be a challenge to firms, especially when users resist the new model (Aladwani, 2001).

Nazir notes that inability to prepare users adequately for the system change is the major cause of ERP failures in the oil and gas sector (Nazir, 2005). In most cases, many employees in the oil and gas industry lack required skills to use ERP systems (Park and Kusiak, 2005). As a result, many firms fail to derive maximum benefits of ERP systems. Oil and gas firms must recognise that employees and leadership are critical success factors during and after implementation of ERP systems (Ocheni, Atakpa and Nwankwo, 2012). Thus, any organisation that fails to consult its employees may suffer poor implementation and adaptation of ERP systems.

Oil and gas firms must understand realities of ERP platforms (Nazir, 2005). For instance, these systems are complex and require re-engineering of organisational processes (Light, 2005). Moreover, ERP systems define their own logic, which firms must observe during implementation. This leads to the concept of ERPs imposed conformity.

Accountability in ERP Implementation

For effective implementation of any ERP platform, oil and gas firms should insist on accountability during the implementation process (Dezdar and Sulaiman, 2009). In this regard, senior executives must be accountable for implementation of ERP solutions in their organisations. Moreover, end users must also be responsible for ERP training outcomes and application of knowledge gained in real-life situations with ERP platforms (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005).

Senior executives must identify the relevance of ERP platforms in their organisations (Ifinedo and Nahar, 2006). As a result, they would be able to understand the importance of accountability during implementation stages. Expectations between senior executives and end users differ significantly (Ifinedo and Nahar, 2006). While senior executives have shown interests in costs and return on investments (ROIs) of ERP platforms, people who use ERP to conduct their operations expect ERP systems to make their jobs easy.

Imposed Conformity

Davenport notes, “ERP tends to impose its own logic on a company’s strategy, culture, and organisation which may or may not fit within existing organisational arrangements” (Davenport, 1998). Genoulaz and Millet observe that ERP systems have important applications, but the challenge is standardisation of operations (Genoulaz and Millet, 2006). Standardisation is difficult for most organisations. Mische and Bennis found out that organisations, which had implemented and experienced success with ERP, had undertaken massive re-engineering of their processes and operations as ways of changing the entire firm (Mische and Bennis, 1996).

This study suggests that implementation of ERP systems should focus on customisation of ERP applications or modules in order to relate them with the current organisational processes, workflow, reporting systems, formats, and required information. It is imperative to involve ERP users during implementation of the system at earlier stages. Studies have also indicated that such re-engineering strategies require close cross-functional collaboration among various business units. While some firms have several modules of ERP platforms, they do not recognise such modules as components of ERP platforms (Keil and Tiwana, 2006; Choi, Ashokkumar and Sircar, 2007).

Specifically, IT firms have noted that significant potential exists in the oil and gas industry under the ‘upstream’ segmentation (Moore, 2008). Upstream entails “exploration of oil and gas, and drilling and operations of wells” (Moore, 2008). Drilling firms handle many assets and several employees, who may work at various sites. Oil and gas firms must rely on ERP platforms in order to ensure effective deployment of available resources (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005).

Firms can also track and account for their equipment. The ERP system also allows an organisation to monitor training and certification programmes for employees. IT integrators have also found it useful to apply ERP platforms during merger and acquisition in the oil and gas industry in order to consolidate opportunities and enhance upstream processes. This has become a common trend in the oil and gas industry today.

Consolidation of ERP platforms brings complexity in re-engineering (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005). A single firm may have several operations in different countries. Moreover, reporting lines for these operations may be different across different countries. In this regard, implementation of the ERP platform in an oil and gas industry should be sequential to reduce complexity.

Effective implementation and adaptation of ERP platforms can lead to reflective conformity (Aladwani, 2001; Gulledge, 2006). The idea of reflective conformity shows that processes and procedures of a firm, which apply in an ERP platform normally lead to improved discipline and create high standards of work with the ERP platform for effectiveness (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005). Thus, control and empowerment of employees through ERP systems show conformity in business processes.

ERP systems require planned training to help employees with change management and adaptation processes (Aladwani, 2001). However, the study showed that a number of oil and gas firms did not concentrate adequately on the needs of end users. Scholars have noted that all aspects of ERP systems should work together after effective implementation (Chang et al., 2008). Training in software and hardware supports and provisions of information are critical success factors in ERP adaptation.

Training of end users often influences employees’ perceptions of ERP platforms in organisations. A study by Bradley and Lee showed that there was a positive correlation between users’ satisfaction with the ERP system training and ERP system outcomes (Bradley and Lee, 2007). It is necessary for oil and gas firms to dedicate a substantial amount of resources for training ERP users. Training should be an on-going process in the oil and gas industry because of the system complexities and frequent changes. The oil and gas industry must consider training as a critical success factor during and after ERP implementation (Kamhawi, 2007).

Effective adaptation of an ERP system requires effective training of all users. Thus, training is an important part of ERP implementation and adaptation. It reduces effects of imposed conformity on end users of ERP systems. Oil and gas firms must identify core business functions, which require thorough training before going live (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005). Firms that fail to identify such areas may not capture the required data for training.

This situation can lead to the failure of the ERP platform. The major challenge that faces both local and multinational oil and gas firms in Nigeria is the lack of adequate resources for training and expensive consultants (Kamhawi, 2007). In addition, inadequate internal skill is a major factor many firms must handle well.

In this context, supports, shared visions, and effective communication from senior executives were critical for the system success (Chang et al., 2008; Motwani, Subramanian and Gopala, 2005). This review supports a previous study by Laughlin who noted that senior executives’ supports were the first sign of successful ERP systems (Laughlin, 1999). Some studies have also shown that executives must participate in the ERP implementation both psychologically and physically for its successful implementation (Jarvenpaa and Ives, 1991). In fact, the study revealed that oil and gas firms, which had management support also, had effective adaptation of ERP platforms. It also affected how users adapted to the system.

Choosing the right ERP Platforms

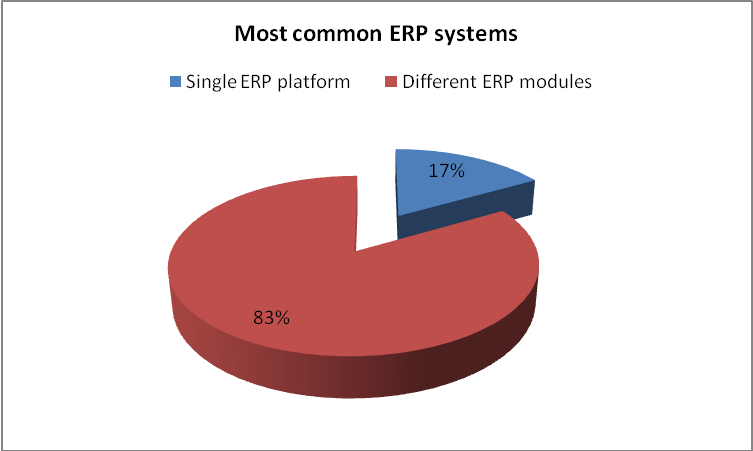

Multinational oil and gas firms tend to have the best ERP systems in the industry. Many of them mainly choose a single ERP platform from top-notch technology firms like Oracle and SAP (Montgomery and Ganl, 2010; Troesch and Schikora, 2010). On the other hand, local oil and gas firms may rely on modules, which serve specific business purposes. Local firms face significant challenges because such modules are expensive, difficult to implement and time-consuming. Moreover, this approach also requires considerable skills for effective implementation and adaptation.

Oil and gas firms require the best ERP systems for their operations (Light, 2005). ERP platforms should be able to show predictable organisational performances as they support actionable and critical decision-making processes in an organisation. Firms search for ERP systems, which can provide exceptional modules for monitoring, forecasting, analysing, and reporting among others within a single ERP platform (Frick, and Schubert, 2009).

This allows key decision-makers to understand important areas of operations and make decisions that drive organisational performance (Ifinedo and Nahar, 2006). Oil and gas firms normally insist on ERP systems with core modules, which are necessary for executing core business operations in an efficient manner. Most ERP systems aim to deliver excellent services by providing the best solutions to users. In these roles, the core objective is to offer the oil and gas industry with the strategic insights, differentiation strategies, enhance productivity, and create flexibility for optimal performance (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005).

ERP developers have recognised that IT has affected different industries in different ways. Therefore, a general observation and conclusion may not be the best approach for understanding ERP systems in an industry. In this respect, many ERP platforms for the oil and gas industry strive to provide standardised or consolidated business operations (Frick and Schubert, 2009). ERP systems aim to create unified business processes for the oil and gas industry across different geographical zones.

ERP systems provide standardisation for several oil and gas firms, which have several wells, geographically dispersed operations, and have complicated supply chain. Thus, the choice for the best ERP platform must aim for a system that can streamline core operations of firms in the oil and gas industry. Re-engineering through standardisation must also aim for cost savings. Firms also derive competitive advantage and flexible processes of managing workflow among various business units.

Oil and gas firms expect changes in terms of workflow and profitability after implementing the ERP system (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005). However, firms, which fail to implement ERP systems to support their operations, do not realise such benefits. Improvement in business processes result from the way in which data flow from the exploration fields, drilling, production, supply, and to specific business needs within organisational units.

The ERP system must aid an organisation to enhance the flow of data from the fields to the whole organisation in the complicated upstream operations. Oil and gas firms also look for secure Web-based ERP platforms, which can help them to manage their operations from anywhere. Such flexibility and freedom are effective ways of deriving competitive advantage from the system. Thus, future ERP systems should provide agility (adapt to changes in the market) to users (Frick and Schubert, 2009).

Past studies have provided valuable information, which oil and gas firms could use to improve their business operations, decision-making processes, forecasting, analysing, and reporting, as well as HR, finance, and other core areas of organisational practices (Frick and Schubert, 2009). Oil and gas industry must ensure effective re-engineering and implementation in order to derive maximum benefits of ERP platforms. Thus, organisations can rely on facts and data for decision-making and not the industry speculations. Managers must show that ERP platforms can have positive contributions to the sector if adapted and implemented well because they have robust modules for core business operations (Ifinedo and Nahar, 2006).

Past studies have identified challenges with the ERP re-engineering and implementation, which Nigeria oil and gas industry could adapt in order to enhance business operations, decision-making processes, forecasting, analysing, and reporting (Martin and Cheung, 2005). The researcher noted that the ERP platforms could solve challenges in the oil and gas industry of Nigeria, but only through effective re-engineering, implementation, adaptation, end user training and provisions of adequate resources to support their entire process (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005; Light, 2005; Martin and Cheung, 2005).

Re-engineering of organisational processes to match the standards of ERP systems was a challenge for many firms (Martin and Cheung, 2005). This was a common problem for local firms, which relied on several modules for different business processes and operations. Respondents identified key areas of focus during re-engineering and system implementation. They noted that many organisations failed to account for change management, employees’ perceptions about the system, and training needs of end users (Aladwani, 2001).

Moreover, they also lacked adequate resources for planning all the required areas for effective standardisation of their systems (Dezdar and Sulaiman, 2009). These challenges could be persistent in the downstream sector due to bureaucratic processes, internal interference, inadequate supports, and resources for re-engineering and implementation (Gulledge and Simon, 2005).

One must recognise that oil and energy companies have some unique characteristics because of diversity in their requirements and complex processes, which may span across several geographical locations. For instance, the industry must focus on fixed asset management, field operation management, customer management, geographical information systems, and management of challenges. These are different needs, which the industry must somehow combine together. The oil and gas industry is aware that not all ERP systems can handle complexities and diverse needs within the industry. Therefore, it is a major challenge for most oil and gas firms to find or choose an ERP platform that can effectively cater for their needs.

Given these challenges, oil and gas firms must evaluate all potential ERP systems for their operations. The overall selection of ERP systems involves consideration of the following aspects for creating business value (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005):

- Enterprise asset management: oil and gas companies have several assets and technical assets. Oil and gas firms can construct new plants or conduct maintenance on their substations. ERP platforms must be able to track all construction, maintenance, costs, and other activities related to the ongoing project and use of assets.

- Support geospatial data: most oil and gas firms rely on geospatial data. There are several aspects of data, which involve assets, inventory, field operations, crew, inventory, and maintenance requirements. Companies must manage these aspects spatially. This approach increases technical issues in data management with ERP platforms. This is a major challenge with the most ERP platforms in the oil and gas industry. It may explain why many firms in the oil and gas industry prefer to use different ERP applications for their core operations.

- Managing field engineering processes: this is critical for efficiency, particularly when constructing or maintaining plants. ERP platforms provide good opportunities for oil and gas firms to leverage operations and manage their engineering processes efficiently. Firms must be able to track their fixed assets, orders, equipment, materials, supplies, and other areas of the supply, which need critical care.

- Outage and challenge management: under some circumstances, oil and gas firms may experience outages. ERP platforms can help them to track areas with problems. In addition, systems can track assets, orders, and different operations in various locations.

- Managing roles and field operations: oil and gas firms need constant management of their field operations and workflows. These are periodic activities, which require logging. Moreover, firms must relate these activities to geospatial, mobile crew, asset management, inventory management, and customer management among others. These processes result in complex management.

- Customer management and billing services: oil and gas firms have several customers with different needs. These consist of both internal and external customers. These firms must deal with basic customer relationships. In addition, they must also handle billing, accounts, and customer service, and oil and gas must integrate such processes with other operations.

The above features can create business value as Jaiswal and Kaisuh noted (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005).

Studies (Frick and Schubert, 2009; Gulledge, 2006; Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005) have that the major challenge among many firms has been finding a single ERP platform that can meet all these diverse needs. This explains why gap analysis is critical for ERP (Gulledge, 2006). Thus, oil and gas firms should define their needs and core differences from other industries. This would allow them to choose the right ERP solutions for their needs.

Oil and gas firms must also acknowledge that a single ERP solution cannot adequately cater for their unique needs, and this requires system integration and optimisation (Worley and Chatha, 2005; Troesch and Schikora, 2010; Montgomery, and Ganl, 2010; Park and Kusiak, 2005; Sammon and Adam, 2005). This implies that firms should consider other applications where ERP solutions may be able to serve their unique needs. Overall, oil and gas firms should consider core areas of their operations when evaluating a suitable ERP platform.

Core areas of ERP implementation planning

- Business re-engineering processes.

- The cost of ERP platform ownership.

- ERP solution for the firm.

- Determining what the ERP system can achieve and what the company needs.

- Customisation of some requirements to meet business practices.

- The project management framework.

- Change management approaches and project time line for meeting various needs like training, stakeholders’ forum, and managing change impacts among others (Aladwani, 2001).

- Aligning ERP systems with legacy systems.

- Data migration planning.

- Cutover methods.

- Resources needed for effective implementation.

- Defining roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders in the implementation process.

ERP implementation requires change management approach. There should be change advocates for the new ERP system in an organisation as Aladwani suggests (Aladwani, 2001). Change advocates are people who are enthusiastic about the ERP system in an organisation. A project champion can be the best change agent for ERP in a firm. Wu and colleagues believe that the process of ERP implementation should be active with involvement of key stakeholders (Wu, Ong and Hsu, 2008).

In most cases, various business units may notice the need for ERP modules in their departments. People who communicate such business needs to decision-makers are likely to play key roles during change management processes. Specific business cases can derive value for a firm if only that firm implement the ERP system successfully. Thus, end users can be able to realise the potential of such a system in their roles.

Communication is also a critical part of ERP implementation planning (Markus, Tanis and Fenema, 2000). The organisation must inform end users how the ERP system will transform their roles, enhance productivity, and reduce cases of errors in reporting. A lack of communication in an organisation can hinder effective adaptation of an ERP system in core business operations. In some instances, employees may continue to rely on simple applications because they do not understand the ultimate goal of deploying the ERP system in the organisation.

Thus, communication to end users about the relevance of an ERP platform in an organisation as a way of overcoming challenges during implementation of the system is an important approach, which firms should embrace. End users who can account for their usages of the deployed ERP system can also provide the needed feedback to support the relevance of the system in the organisation (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005; Kamhawi, 2007). Thus, any head of a department who presents his or her ERP case to senior executives must also be ready to inform end users to adapt to the system in order to ensure that the firm realises its ERP intended objectives and benefits.

Business Process Reengineering

Most oil and gas firms in Nigeria consider ERP implementation, business process re-engineering, and subsequent adaptation as favourable chances for enhancing performance by improving business processes and operational efficiency. Effective business process re-engineering for oil and gas firms can provide various forms of services, which can enhance flexibility for business operation improvement (Light, 2005).

Oil and gas firms should have the expertise to deploy business re-engineering processes at any stage when selecting or implementing the ERP system. For instance, most of the Nigeria oil and gas firms can concentrate on baseline issues with regard to current practices, business processes, implementation, and adaptation challenges. These firms can then improve their business operations by reducing wastage of time and resources, enhancing and optimising main business processes (Moon and Phatak, 2005). In addition, they can also choose to improve efficiency in every unit of the business throughout their entire firms.

The major aim of business process re-engineering with ERP solutions is to help firms to transform their current business practices through rethinking and redesigning business processes (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005). This would allow them to achieve efficiency and flexibility in operations. Firms should develop ERP blueprints to drive the re-engineering initiatives and customisation processes by improving past processes in order to optimise benefits.

Oil and gas firms in Nigeria can re-engineer their business processes and performance management based on the best principles like the Six Sigma. This can ensure that such firms achieve comprehensive and holistic understanding of their current business processes (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005). They must draw detailed recommendations for enhancing efficiency and operational excellence in order to meet strategic objectives based on the aims of deploying an ERP system.

In this regard, oil and gas firms should include different phases in their business re-engineering processes as various studies indicate (Dezdar and Sulaiman, 2009; Martin and Cheung, 2005; Moon and Phatak, 2005; Nazir, 2005; Mische and Bennis, 1996; Manoj, 2013).

Firms that have re-engineered their business processes in phases have been able to identify core requirements in their business processes and procedures. For instance, Light noted that business processes improved after processes customisation, which involved gap analysis and customisation of processes to meet specific business needs (Light, 2005). In this case, the processes involved systematic and phased re-engineering processes (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005). Re-engineering phases included:

- The first stage involves process mapping in which oil and gas firms should identify their current practices and main performance indicators, which they use to determine general performance against the industry best practices.

- The second stage is business process improvement and optimisation. Oil and gas firms of Nigeria should perform the root cause analysis in order to understand their current issues and develop the best approaches for managing future operations through ERP systems.

- The final stage involves continuous improvement of business processes. Oil and gas firms must establish the support and required structures to allow them to enhance their operation efficiency and reduce costs through deployed systems.

Main areas in which oil and gas firms should focus on during re-engineering processes include the following areas as Nazir (2005), Moon and Phatak (2005) and Manoj (2013) have identified in their models:

- Benchmark assessment of core business processes.

- Process mapping for ERP implementation.

- Analysis of current situation for improvement.

- Developing technical blueprint for ERP implementation, re-engineering, and adaptation.

- Evaluating ERP readiness.

- Understanding potential impacts of changes.

- Redesigning structures and processes.

- Assessment of ERP financial implications.

- ERP return on investment and business outcomes.

- Continuous improvement of business processes.

- End user training for effective adaptation with the new ERP system.

- Leadership support.

- Change management strategies.

- Support and other services necessary for the ERP success.

The above core areas can lead to improve performance and process optimisation in organisations (Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005; Kamhawi, 2007).

ERP Staffing

Most firms do not have the required resources or expertise to cater for complex processes and workload involved during the ERP implementation (Kamhawi, 2007). In order to ensure that oil and gas firms operate efficiently with ERP platforms, they must increase the number IT professionals for both short-term and long-term operations. Oil and gas firms should account for their mobile workforce and employees’ training needs in order to use ERP systems effectively. They should be able to adapt the new systems to meet their current needs or re-engineer their staffing practices to match ERP best options (Jarvenpaa and Ives, 1991).

Staffing needs should account for technical expertise in core areas of ERP usages (Kamhawi, 2007). Staffing applications should demonstrate clear focus on enhancing business processes. Moreover, employees should have knowledge and skills for their operations (Umble, Haft and Umble, 2003). This would ensure that they utilise ERP applications for optimal benefits (Romero, Anderson, Banker and Menon, 2005).

During ERP implementation, oil and gas firms should ensure that they have effective leadership and expertise in core business areas, which would guarantee effective implementation of the system (Worley and Chatha, 2005; Ocheni, Atakpa and Nwankwo, 2012). It is important for firms to have ERP implementation teams and managers. From these teams and managers, oil and gas firms can get different expertise to manage various processes, such as change management, data strategy and migration, system trainers, re-engineering and integration experts (Park and Kusiak, 2005). Moreover, firms may also seek for external assistance from qualified or certified ERP experts if internal expertise cannot ensure effective implementation of new ERP systems.

Research Methodology

The main research objective sought to demonstrate how Nigeria oil and gas industry adapted to the imposed conformity of ERP platforms. This implied that such firms must also identify critical success factors for their ERP platforms.

This part of the study provides the method of collecting the required information to respond to research questions. Howe and Eisenhardt observed that methodology must be “judged by how well it informs research purposes, more than how well it matches a set of conventions” (Howe and Eisenhardt, 1990) after data analysis. Therefore, the objective of the methodology is to gather data that answer the research questions, present coherent background assumptions, and to ensure that methods used guarantee the credibility of the study results.

A well-formulated study must show a theoretical frame, scientific design, measurement methods, which show reliability and validity, apply suitable statistical methods of data analysis, and generalize results to allow other researchers to borrow and apply the same approach in other areas (Creswell, 2008). Therefore, theoretical background, defined objectives, research methods, confidence in conclusions, and understandable study implications are “important and determine which research methods would be appropriate for the particular study” (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2012).

There are a number of methods of data collection in research. This study relied on both qualitative and quantitative methods (mixed methods approach) to collect the required data for understanding the imposed conformity and adaptation challenges in the oil and gas industry of Nigeria (Creswell, 2008). Qualitative research accounted for non-numerical data. Thus, this technique allowed the researcher to explain and interpret data for the study. On the other hand, quantitative study focused on “numerical data from quantitative research” (Trochim, 2006).

The study used a mixed method approach in order to get the following advantages. First, the researcher wanted to establish validity through triangulation. Triangulation involves substantiation of study findings (Creswell, 2008). For instance, the researcher used mixed methods approach in order to assess whether imposed conformity could affect adaptation of ERP systems in Nigeria oil and gas industry. Second, the researcher wanted to establish validity and interpretability of the study. Third, mixed methods approach allowed the researcher to use results from both approaches in order to improve and inform the other approaches (Kumar, 2010).

For instance, quantitative research results were useful in the qualitative study in which the research wanted to provide in-depth accounts of the oil and gas industry practices when re-engineering and implementing ERP systems (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2012). Fourth, mixed methods approach was imperative for gathering the necessary data for deep understanding of research questions. The researcher was able to comprehend the application of ERP system insights during the study due to the use of qualitative method, which allowed him to change the study in order to show usages of ERP systems in the oil and gas industry.

It is difficult to plan for emerging insights in the study during research design because they develop during data collection. Finally, mixed methods approach provided an opportunity for the researcher to define the scope of research. For example, the researcher applied qualitative approach as a way of probing decision-making processes among senior executives when considering ERP platforms, and a quantitative approach in order to study their expectations and outcomes (Steinberg, Bringle and Williams, 2010).

This was a descriptive study with a mixed methods approach (Creswell, 2008). The researcher described and explored the oil and gas industry in Nigeria with the aim of understanding processes and procedures during ERP system implementation and organisational re-engineering. The researcher used both closed-ended questions and open-ended questions in order to collect data that could provide adequate responses for the study research questions (Yin, 2008).

Sample

The researcher used random sampling (Creswell, 2008). The sample was adequate to allow the researcher to generalize the results to other oil and gas firms in Nigeria. A suitable sample allowed the researcher to conduct a detailed study of gathered data (Bazeley, 2002). Bazeley observes that such studies are possible because of computer software, which can analyze data from both qualitative and quantitative respondents.

Random sampling allowed the researcher to collect data from representatives of study samples. All samples had equal chances of participating in the survey (Bui, 2009). This approach also allowed the researcher to find respondents without challenges. This study was unbiased because of random selection of the study participants. Therefore, it provided good opportunities for the researcher to draw a generalized conclusion from the study. The aim of the researcher was to be able to draw a conclusion that reflected the study subjects.

Specifically, sampling involved the use a simple random sample (Yin, 2008). The researcher chose senior management team in the oil and gas industry from a large set of respondents. He chose every research participant randomly through chance. This implies that all members of the targeted group had the same chances of being chosen in the sampling process. This ensured that the research process was not biased, but objective (Steinberg, Bringle and Williams, 2010).

This is the fundamental form of research sampling, which ensured that any manager had the same chances of taking part in the study.

The researcher wanted to make sure that he had unbiased sample through random selection of research participants. This approach ensured that the sample represented all oil and gas firms in the industry of Nigeria. However, the researcher could not guarantee that the sample was perfect and free of errors. Rather, it allowed the researcher to draw a valid conclusion about the study sample.

Although this was the simplest form of random sampling method, it needed a complete list of all oil and gas firms with any form of ERP platform or ERP modules in Nigeria. This was difficult to obtain because some firms did not recognise their applications as ERP modules.

This method reduced instances of mistakes in identification of research participants (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2012). The researcher did not need prior knowledge about senior executives and IT managers in the oil and gas industry of Nigeria. Thus, it was a suitable approach to conduct the study because the current list of all local oil and gas firms in Nigeria was not readily available. In addition, data collection was suitable for the study because of random distribution of study participants.

Sample size

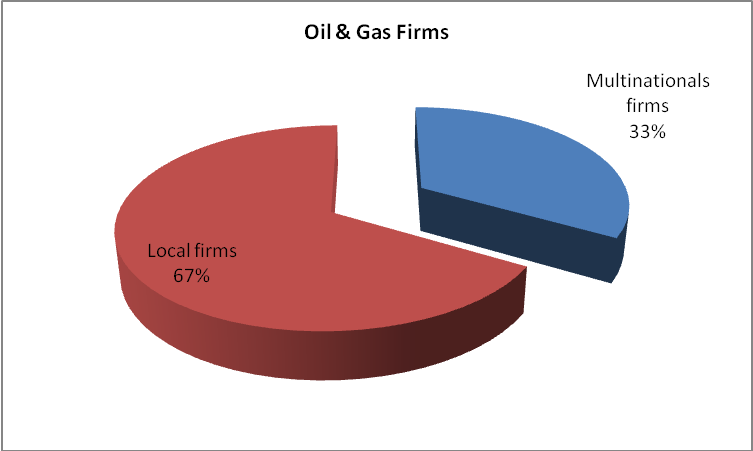

The researcher used four multinational oil and gas firms in Nigeria in the upstream segment and eight local oil and gas companies in the downstream segment. Thus, study participants were 12 respondents.

Study Instruments

The researcher used open-ended questionnaires to collect data from research participants (Patton, 2002). Questionnaires were appropriate for this study because they assisted the researcher to collect data on imposed conformity among oil and gas firms in Nigeria. The researcher had to develop valid and reliable questionnaires for the study.

Procedures

The researcher studied the study objectives and research questions. He identified research participants as IT managers and senior executives. At first, the researcher conducted a review of past studies on imposed conformity, ERP system implementation, re-engineering, and adaptation challenges. This was imperative for developing a methodical understanding of ERP systems in Nigeria oil and gas industry.

The researcher developed questions for the study regarding the appropriate ways of understanding challenges of imposed conformity (Steinberg, Bringle and Williams, 2010). This stage accounted for a thorough understanding of literature review and theoretical concepts of the study. The researcher concluded that ERP imposed conformity was a major challenge in the oil and gas sector of Nigeria. Thus, it was necessary to understand how multinational oil and gas firms in Nigeria adapted their ERP systems in the same location. The researcher also linked the research questions with the study objectives (Kothari, 2004).

Questionnaires informed the order of questions and data analysis techniques for data collected (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2012). The researcher had to establish the relationship between research measurement instruments and the suitable method of data analysis. The researcher had to select an appropriate technique for understanding study questions. Descriptive statistics provided the basic information about the collected information for the study.

Descriptive statistics was good for analyzing collected data (Patton, 2002). The researcher presented simple summaries about key issues in ERP systems. The graphical elements in descriptive statistics presented a basis for analysis of quantitative data in the study. The researcher used descriptive statistics to present results from data analysis (Bui, 2009). This presented data in a manageable form, which many readers could understand. This ensured that the study had some charts.

The researcher applied content analysis in order to understand what managers perceived as advantages and critical success factors for companies when deploying ERP platforms (Patton, 2002). This was the best approach for analyzing qualitative data obtained from the interview. Content analysis involved conventional, directed, and summative methods, which aimed at interpreting results of the study and adhering to naturalistic paradigm of qualitative elements of the research design. The researcher had to maintain trustworthiness of the data during coding of themes. He derived themes directly from the collected data. As a result, the researcher was able to account for research hypothesis and research questions based on data analysis techniques used.

The researcher applied content analysis in all study questions, which had elaborate description of study accounts and analytical responses. These were mainly open-ended questions, which sought to provide in-depth knowledge in ERP systems and their adaptation in Nigeria. Patton referred to content analysis as “any qualitative data reduction and sense-making effort that takes a volume of qualitative material and attempts to identify core consistencies and meanings…often called patterns or themes” (Patton, 2002, p. 453).

The researcher then established the validity of the research instruments.

He then reviewed the instruments with a panel of experts on the field of study and conducted a pretest. The researcher then ensured that the questionnaire was valid, i.e., the questionnaire “measured what it was intended to measure” (Norland, 1990). The instrument also represented the study content, was appropriate for various participants, and comprehensive to collect adequate information for the study.

The researcher also obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and ensured that the study met all ethical standards of study, which involved the use of human participants. He then conducted a test with different participants and made changes to questionnaire based on the test results.

The researcher used pilot test results to determine reliability of the research questionnaires. This aimed at ensuring that the questionnaire was consistent with what it was designed to measure. Overall, the researcher followed “appropriate and systematic procedures in questionnaire development, testing, and evaluation to avoid undermining the quality and utilization of data” (Esposito, 2002).

Design and statistical procedure

Senior managers in the oil and gas firms on Nigeria took part in the study. The researcher interviewed them in order to get in-depth information about imposed conformity and subsequent adaptation of ERP platforms in the oil and gas sector of Nigeria (Creswell, 2008). The aim was to understand the purpose of choice, firms’ strategies, perceptions, benefits, and impacts of implementing ERP platforms in their operations and processes.

The researcher presented both open-ended and closed ended questionnaires for the study. This was to demonstrate how managers interacted with ERP platforms and what other employees perceived as the important functions of ERP systems in their firms. Managers also had to show whether they understood the concept of ERP imposed conformity and organisational re-engineering to match ERP requirements, it advantages, challenges, and any other emerging practices.

The next stage involved the plan for data analysis. The researcher also had to decide on what to do with the collected information after analysis. There were both quantitative and qualitative data collected for the research questions. The researcher used descriptive statistics in order to provide study results for quantitative data. He carefully considered descriptive statistics based on the study instrument developed during the research design. However, this was not common in the data gathered.

The researcher noted that qualitative data were suitable for content analysis by identifying themes, which were common based on responses from respondents (Steinberg, Bringle and Williams, 2010). The researcher used coding method to identify themes. Thus, themes were the important foundation on which the researcher derived ERP system challenges during re-engineering and implementation (Marshall and Rossman, 2010). The researcher summarized and presented results of the study to research supervisor for review and comments.

Findings

The researcher used both multinational (four) and local (eight) oil and gas firms in Nigeria in the study. Imposed conformity was a major challenge among several oil and gas firms in Nigeria. While multinational firms could respond to such challenges quickly, several local firms could not effectively adapt to ERP modules in their systems.

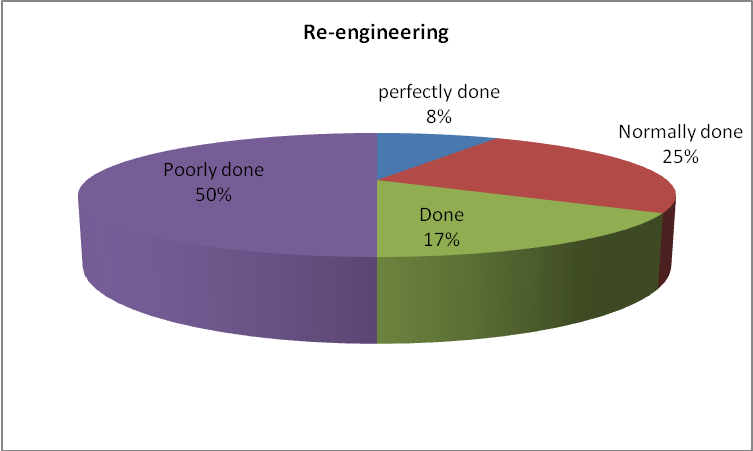

Many firms admitted that they did not perform re-engineering of their business processes and operations to meet ERP system standards. As a result, implementation of ERP platforms did not give the desired results. In addition, these firms often found out that effective adaptation to ERP systems was a challenge. This explained why ERP systems have not achieved the intended outcomes among several Nigeria oil and gas firms.

Oil and gas firms in Nigeria often choose ERP systems, which can standardise their business operations globally. However, seven local firms (87 percent of all local firms that took part in the survey) had different ERP modules for specific core business areas. Generally, they wanted systems, which could monitor, forecast, analyse, and report all business processes and operations. In addition, ERP systems had to focus on core areas like HR, finance, field operations, reporting, and supply chain management.

Table 1: Key modules for Oil & Gas ERP systems.

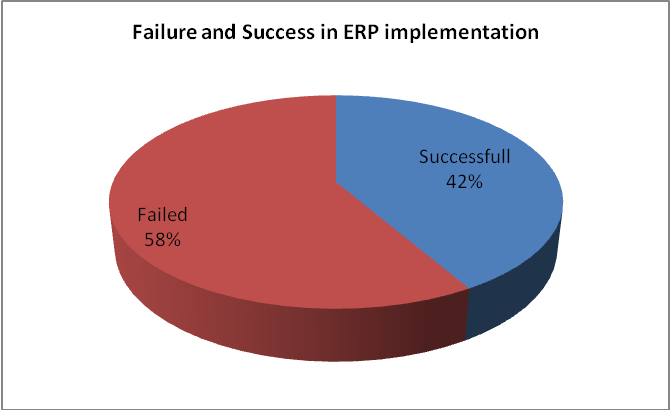

Oil and gas firms expected smooth processes, cost saving, standardised processes and operations, and unique competitive advantage after implementation of ERP platforms. However, post-implementation challenges affected these expectations among several oil and gas firms in Nigeria (fig. 5 shows that 58% of all firms, which implemented ERP solutions failed).

This situation often led to poor adaptation of ERP systems among Nigeria oil and gas firms. As a result, implementation was a challenge, which led to difficulties in understanding of ERP systems among end users because of difficulties in data conversion. Moreover, re-engineering processes failed to address complexities of ERP systems, especially in different modules.

Challenges

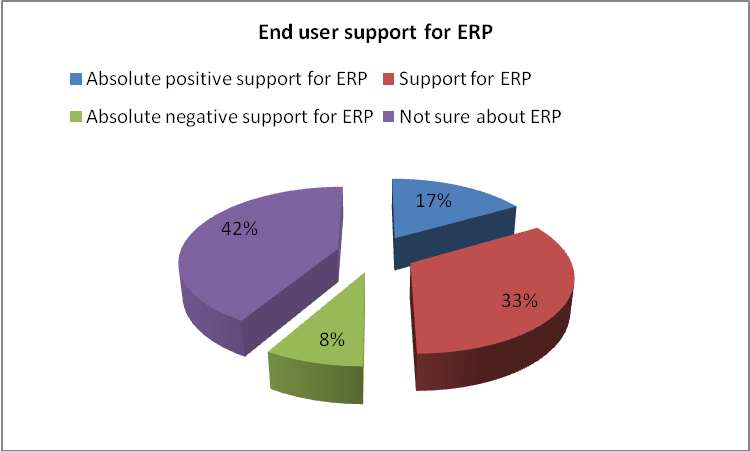

The Nigeria oil and gas firms experience challenges of managing employees’ expectations and fears when implementing ERP platforms. Many employees (33%) do not embrace ERP systems because they believe such systems are complex and eventually would replace them. Most end users also claim that ERP systems force them to abandon their regular practices and follow rigid standards. Majorities (42%) of employees show are not sure about their support for ERP introduction.

From 12 firms that took part in the survey, seven reported failures due to technical processes during implementation (fig. 6). One major aim of an ERP solution is to provide data for quick decision-making. Thus, managers should ensure that end users rely on ERP systems to provide data for decision-making. However, adaptation to the new system among many end users was difficult.

Many companies often ignored some phases during selection and implementation of ERP systems. For instance, a number of companies (out of 12 firms in the survey, seven rarely conducted any meaningful gap analysis as indicated by the failure rate in fig. 6) failed to conduct gap analysis. Gap analysis is an important stage during ERP implementation. It allows firms to know their current ERP positions and where they want new ERP systems to take them.

Gap analysis should help firms to develop a model that identifies needs and existing gap. Failure to conduct a gap analysis led to poor implementation with unrealistic goals because from a gap analysis, firms would realise that no single ERP platform could meet their unique challenges and business processes.

Re-engineering remained a critical phase for conforming or meeting ERP imposed applications. Re-engineering in this process involved redefining employees’ roles and business processes with the aim of managing imposed conformity. In this context, many employees consider re-engineering phase as a downsizing strategy (see table 2). However, re-engineering applied to both technical operations and business processes.

The fundamental focus of re-engineering in the Nigeria oil and gas industry failed to account for the human factor. In most change management strategies, re-engineering approaches have often emphasised human factors, which could have significant influences in an organisation during change management. The argument for re-engineering process is that it accounts for both business processes and human related factors during ERP implementation.

Table 2: Why employees do not favor re-engineering.

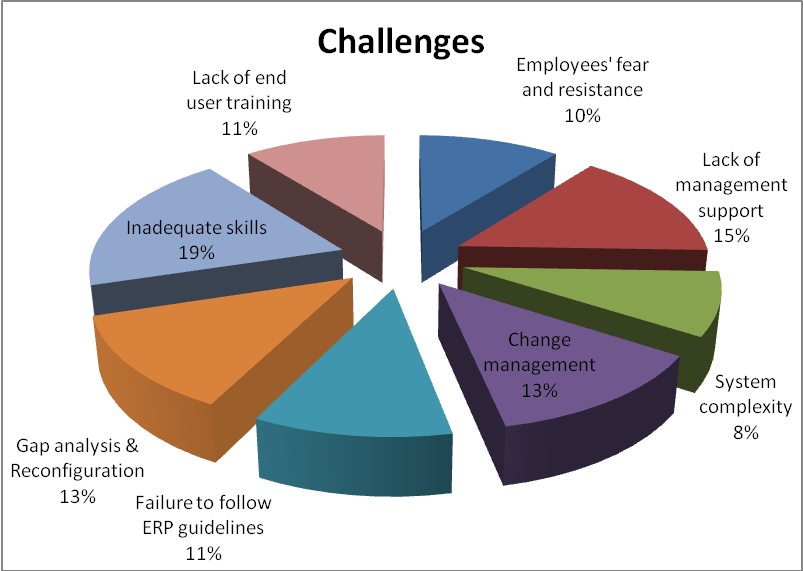

Another challenge was in the configuration of the ERP system (see fig. 8). In most cases, ERP consultants look for potential problems in the system before going live. Tests in this stage should highlight both strengths and weaknesses of the system. However, many firms did spend adequate time to determine how configured systems could not work and their effects on identified gaps. Lack of skilled employees contributed to configuration and adaptation challenges. In addition, configuration focused on various core functions like HR, field operations, and financial among others. This increased the complexity of the system.

Failures to provide adequate resources for training employees impacted negatively on post-implementation activities. For instance, 58% (mainly firms with failed ERP implementation) lacked skilled people to train end users. In addition, firms did not select employees who could get training on ERP systems and train others. Various modules of the system also complicated testing processes because 83% of the firms (ten firms) relied on different ERP modules, whereas only 17% (two firms) had single ERP systems. Companies did not identify possible sources of weakness before deploying the system on a real-time basis.

Some of the technical challenges experienced in different phases did not allow firms to achieve the full potential of ERP systems. Moreover, ERP systems did not receive full support from employees who feared such systems would replace them. Some firms (58% – fig. 6) lacked trained experts to handle emerging challenges after implementation. The right skills, new versions, upgrades, and integrated processes all affected the final outcome of ERP benefits to companies.

One could conclude that inadequate skills, gap analysis, and lack of end user training were the major challenges many oil and gas firms experienced when re-engineering and implementing ERP solutions.

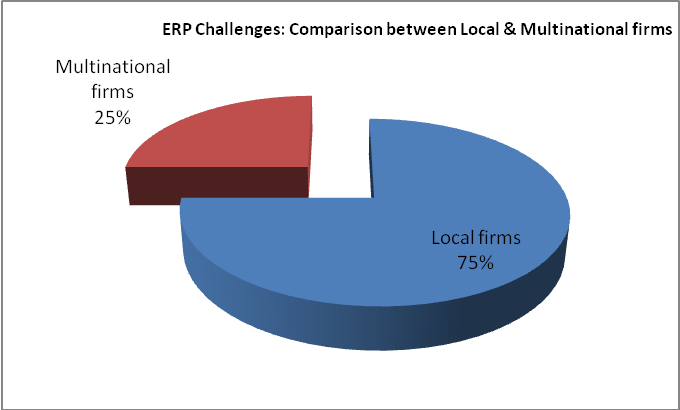

These challenges were manily prominent in local firms as six (75%) showed that they experienced these problems. On the contrary, multinational firms also faced these challenges, but on a low rate (one out of four firms had such challenges).

Discussion

The study shows that multinational oil and gas firms operating in Nigeria have effective ways of managing imposed conformity as they strive to adapt to ERP systems in their operations (see fig. 9). Previously, some multinational oil and gas firms relied on ERP systems based on local processes with a combination of several bespoke modules, which were mainly standalone applications (fig. 7 shows that many firms rely on different ERP modules).

These firms realised that such systems were complex and expensive to run. In addition, they also threatened the efficiency of operations. In response to such challenges, most multinational firms have standardised and integrated important operations onto one ERP system (Montgomery and Ganl, 2010). These companies consider such systems as global solutions for their upstream operations. They focus on processes, workflow management, procurement, logistics, finance, and reporting.

Many local oil and gas firms, mainly in the downstream oil and gas industry, have not responded to ERP technologies adequately (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005). They rely on many modules for various purposes. Still, other local firms do not consider such modules as ERP systems or components.

The study shows that effective implementation of ERP systems could lead to improved adaptation (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005). However, firms that fail to re-engineer their operations to meet ERP standards also experience challenges after implementation of ERP systems. Thus, there were several challenges after implementation of ERP systems in many firms. ERP systems did not meet expectations of the firms. There were challenges with data accuracy, missing controls, elongated transaction periods, and operation difficulties.

It is interesting to note that most oil and gas firms, which noticed challenges with the adaptation of ERP systems often formed committees to review the problems and development action plans for progress. From the study, one can note that most oil and gas firms in Nigeria struggle to meet ERP system standards.

The study revealed that change management and re-engineering strategies (this accounted for 13% of the challenges) during implementation of ERP systems were major challenges in the industry (Aladwani, 2001). Many firms recognised that ERP systems were transformational in nature, particularly where they focused on the entire organisation, and all employees relied on the system to conduct their operations. Firms acknowledged that ERP systems involved significant investments, but there were also critical implementation challenges during the re-engineering phase.

In the study, the researcher noted that many local oil and gas firms did not spend enough resources to plan on re-engineering strategies and effective implementation of the system. Most firms failed to recognise that ERP systems required adequate planning because of its complicated modules and subsequent adaptation with the business practices (Worley and Chatha, 2005). Many oil and gas firms mainly focused on resources spent on ERP platforms.

The researcher noted that employees’ perception of ERP systems, implementation, and adaptation were critical (Kamhawi, 2007). Many employees believed that ERP platforms would make them redundant and take their roles in core areas like finance, HR, and in the supply chain management. Such beliefs affect implementation and adaptation of ERP systems in oil and gas firms in Nigeria. Fears among employees affected implementation and the re-engineering phase of ERP systems implementation. As a result, most of the ERP systems had weak control systems. This implies that the generated data could be questionable and doubtful.

Oil and gas firms, which relied on different modules, noted challenges with data compatibility (Van Everdingen, 2000). Organisations should maintain data in a specific department and share such data across the entire organisation. However, this was a major challenge among downstream oil and gas firms in Nigeria because of state influences and internal issues.

Users did not get adequate training to ensure effective adaptation to ERP systems. Most of the oil and gas firms in Nigeria did not provide adequate training to end users of ERP systems. Umble and colleagues have observed that training was an effective way of ensuring the success of ERP systems (Umble, Haft and Umble, 2003).

The Downstream Sector

The downstream oil and gas sector in Nigeria is under heavy influences of the government. Thus, it experiences additional challenges from bureaucratic processes in procurement systems for improving business operations.

A number of factors may hinder ERP usages in such an environment. For instance, managing the oil and gas sector as a public entity can increase complexity in the process (Gulledge and Simon, 2005). Moreover, the prevailing political environment may hinder some initiatives, which aim at transforming operations for efficiency.

Complexity in operations may also result from different customer characteristics, government objectives, organisational cultures, and state regulations. It even becomes difficult as the demand for public accountability amidst inefficiency increases.

The downstream oil and gas segment should respond to these challenges by adopting efficient and responsive approaches. Firms in this segment must make the government to realise that fiscal discipline and enhance performance of the public sector is critical for success of the segment. Thus, they must adopt technologies, which would streamline operations and enhance efficiency in operations. Oil and gas firms in the downstream segment should have data to back their claims for ERP systems. These data could reflect improved efficiency, cost management, and decision-making processes. ERP can be an effective tool for creating changes in the downstream segment of the oil and gas industry in Nigeria.

The oil and gas firms experience diverse challenges when implementing, re-engineering, and adapting to ERP systems (Gattiker and Goodhue, 2005; Montgomery and Ganl, 2010). Challenges normally arise from different modules of the system and subsequent effects on the firms’ business operations and processes.

The aim of an ERP platform is to “offer a real-time integrated system that can capture all required data on a single platform” (Sammon and Adam, 2005). Earlier planning for ERP implementation can avert some potential challenges, which firms face when centralising their core business operations.

Oil and gas firms have noted that ERP implementation has various challenges, which are mainly about its value addition and economic returns after deployment (Kamhawi, 2007). ERP systems have several potential benefits after implementation. However, challenges remain fundamental in the Nigeria oil and gas industry. Firms should understand potential challenges with ERP systems before deployment and integration with the existing systems. Successful re-engineering, implementation, and adaptation can eliminate possible problems and enhance benefits from the system.

Oil and gas firms in Nigeria identified the following challenges during ERP re-engineering, implementation, and adaptation.

First, firms often experience ERP application integration challenges. There are a number of functional applications in ERP systems. In addition, integration may involve the old legacy or several modules from different developers or vendors. In some cases, the modules may have different versions. In addition, oil and gas firms must also manage technical processes of integrating other platforms like customer relationship management, supply chain, information management, and other systems. Still, the integration of the ERP platform with the existing platform could be cumbersome than integration with other applications. The main challenge is managing data transfer. As a result, firms often seek for a third party interface between the old system and the new ERP platform.

Second, some firms have a common fear about ERP implementation (fig. 5 shows that 12% of the challenges originated from employee fear and resistance). Firms, which have learned about failed ERP projects, expressed their fears about the system. Failure of ERP systems may result from several factors. However, it is imperative for oil and gas firms to select the right ERP platforms and vendors for their initiatives. This would reduce cases of failed projects in the sector.

Third, some firms have raised the issue of a lack of competitive advantage from the system. Firms have noted that ERP implementation does not offer any instant advantages. As a result, many companies have expressed their concerns whether or not ERP platforms can provide effective results and return on investment. Thus, oil and gas companies should conduct a thorough evaluation of the ERP system, IT strategic objectives, and expected results from the new system.

Fourth, ERP platforms are time-consuming and expensive ventures. Firms must spend considerable amounts of resources before they can realise benefits of ERP platforms. Some of the associated costs during implementation phases include analysis of the existing gap, organisational re-engineering, customisation, implementation costs, training expenses, maintenance, and support service costs. Many firms have failed to plan for costs related to system maintenance and support services. As a result, they often reduce such costs.

Fifth, it is often difficult to identify what an ERP system can achieve and what it cannot do to an organisation before deployment. However, oil and gas firms fail to conduct a trial before deployment in order to determine what the new system can achieve. Conducting a trial before deployment can aid in identification of the system limitations and potential challenges when in use.

Sixth, resistance to change is common in all industries and the oil and gas industry of Nigeria in no exception (Aladwani, 2001). Most business units often resist changes from their current platforms to new ERP systems. The major challenge is substituting a regular application with an unknown one, which could also influence decision-making authorities within the organisation. Thus, senior executives and the IT department must explain the role of the ERP system and its potential benefits so that employees can embrace it as a tool for efficiency and business development.

Finally, many oil and gas firms faced a challenge of implementing partial modules of ERP systems. ERP system requirements may differ from one firm to another one. Thus, a single platform, which can meet all requirements, may be difficult to obtain while customisation may not produce the desired results. Adaptation of ERP platforms to the company’s practices may indicate that the ERP system should only perform the selected roles (Light, 2005; Jaiswal and Kaushik, 2005; Markus, Tanis and Fenema, 2000). While ERP systems may be flexible to allow for customisations, they do not easily allow for additional of other functions.

The Nigeria oil and gas industry faces these technical challenges before, during, and after ERP implementation, re-engineering, and adaptation (Dezdar and Sulaiman, 2009; Aladwani, 2001; Light, 2005). Thus, the success of an ERP platform depends on how well an organisation can control these challenges.

Managing ERP imposed conformity during implementation in Nigeria oil and gas industry