Investing Behavior

There are different types of investors. One of the categorization systems has three types of investors: pre-investors, passive investors and active investors. Another way to single out different types is based on determining investing behavior and willingness to tolerate risks, in particular. Which can be defined as the extent of variability in investment returns that an investor is expected to handle in the selected financial planning. Risk tolerance considers the key risks observed in the market of the company’s choice, including stock volatility, swings in the stock market rates, economic or political factors, political and economic concerns, and many more. After considering these, an investor decides whether the currently approved strategy will help to handle the outlined risks.

Remarkably, my investor profile has not changed in any significant way except for a greater awareness of the strategies for mitigating risks. However, the specified alteration can be considered an essential shift in perspective since it implies a noticeable change in investor behaviors, as well as a different approach toward market research and company analysis. With a closer look at the factors and pieces of data that could signal a potential threat, one can avoid the instances of financial fraud. Thus, I believe that the change observe din my behaviors and skills as an investor indicates a more mature and balanced approach toward making investment decisions.

The levels of risk tolerance depend on a variety of personal factors such as age, the level of expertise, and the extent of experience. My Investment Risk Tolerance Score: 29. The levels of tolerance often define the propensity toward taking chances in the target market and develop[ strategies for mitigating negative outcomes. Personally, I would assist a financial advisor by suggesting changes to the corporate policies and insisting on transparency. Coupled with regular audits, the specified measure will help to avoid the cases of fraud and minimize the probability of schemes.

Recognizing Fraud

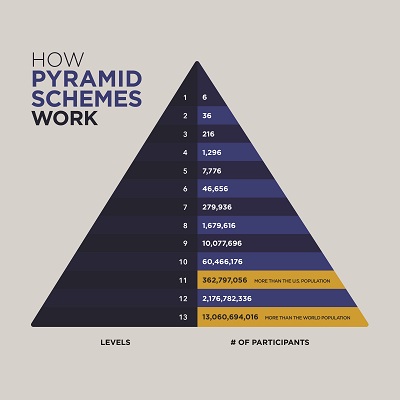

A pyramid scheme is a framework of moneymaking that relies on fraud and illegal strategies for making money. The scheme implies creating a chain of recruits that attract new ones, thus locking the process in a perpetual circle. Due to the exponential increase in the number of investors, the scheme received the title of a pyramid in reference to its expansion form a single top point to the massive base. Personally, I have never participated in a pyramid scheme, and neither have I ever been associated with any of the ventures of such kind. However, I have heard about them quite a lot since they used to be notorious in the business world as tools for tricking people into supplying money to scam artists.

In the classic “pyramid” scheme, participants attempt to make money solely by recruiting new participants. As a rule, all pyramid schemes are based on the same premise containing three main principles. These include luring gullible investors by promising high returns within a short time period, having no actual products to sell, and relying on gaining new participants, whose money will be used to pay to the old ones (Mohammadi & Shafi, 2018).

It is also worth remembering that recognizing a scheme such as a pyramid fraud may turn out to be far more difficult than one might initially believe. The main reasons for pyramid schemes and the relevant fraudulences to be so elusive for justice include their surprisingly good ability to disguise themselves as legitimate projects and business ventures (Bosley, Bellemare, Umwali, & York, 2019). Bosley et al. (2019) explain that the ability of pyramid schemes to mimic the companies using direct selling as their main vehicle for performing transactions with customers defines is the main reason for such frauds to remain uncovered until it is too late.

In addition, complexity of payouts and the related financial processes allows organizations that take fraudulent actions and create financial pyramids to remain undiscovered. Hiding beyond the façade of incomprehensibly complicated compensation plans, organizations that build their framework based on a pyramid scheme benefit from the lack of financial control and the challenges that disentangling the payout framework entail. Therefore, it is crucial to provide control tools to corresponding authorities so that financial audits and similar measures could be carried out more effectively and with greater precision rates.

However, there are some ways of spotting an instance of fraud. For example, if an unreasonably large amount of inventory needs to be purchased regularly, the company may possibly be running a pyramid scheme. In addition, in case the company’s income correlates primarily, or only to the number of people recruited, there are reasons to suspect a pyramid scheme (Rastuti & Pharmacista, 2019). Finally, frequent purchases of largely unnecessary and mostly expensive products supposedly intended for the improvement of performance is also indicative of a pyramid scheme (see Fig. 1) (Rastuti & Pharmacista, 2019). The dependency on the increasing number of investors is the main source of a pyramid scheme’s unsustainability. However, unlike with honest businesses, the victims of pyramid schemes only include their customers and investors. Therefore, it is crucial to build awareness regarding how to spot pyramid schemes accurately.

The Madoff Scheme

Considering some of the most infamous instances of pyramid schemes, one must recall the notorious Madoff affair. The specified fraud involved collecting money from wealthy Jewish entrepreneurs, with his supporters growing increasingly rich with every passing day. However, after a thorough investigation, it was discovered that the specified project was based on a massive Ponzi scheme (Hidajat, 2018). The phenomenon of a Ponzi scheme implies using the money supplied by new investors to pay to the old ones (Obamuyi et al., 2018).

Despite having finally been rightfully labeled as a Ponzi scheme, the Madoff affair required quite a lot of resources to be identified as such (Hidajat, 2018). The fraud was spotted by Harry Markopolos, who worked as a securities industry executive at the time (Hidajat, 2018). Markopolos’s boss asked him to figure out how the Madoff business managed to thrive so copiously, which led to Markopolos locating inconsistencies in the financial framework used in the Madoff business (Obamuyi et al., 2018).

Madoff’s victims mostly included minor investors and SMEs, who trusted in the newly emerging organization as the vehicle for advancing in the market. Unsurprisingly, the strategy that Madoff used to defend himself against the accusations against him were based mostly on his ignorance of the actions carried out in the firm. On the one hand, the specified line of defence appeared to be blatantly false and dishonest; however, on the other hand, it allowed him to shift a significant portion of fault onto the circumstances surrounding the case, thus, reducing the amount of his guilt.

In retrospect, the Madoff affair was far from perfect, yet multiple businesses accepted it without questioning possible flaws in its ethics. Investor biases deserve to be mentioned as the reason for the specified situation to have taken place (Quisenberry, 2017). Namely, the familiarity bias may have played a part in convincing organizations to support the Madoff scheme (Gurun, Stoffman, & Yonker, 2018).

Since the organization was becoming a truly powerful entity, the reasons for assuming that it involved any risks to its stakeholders appeared to be ungrounded. Additionally, the presence of self-attribution biases may have affected investors’ decisions as they assumed that honesty and integrity was an inherent part of any business with which they collaborated (Quisenberry, 2017). Finally, the bias of the need to chase trends could also have been a factor in multiple organizations believing the Madoff affair and investing in the pyramid (Gurun et al., 2018). Although the range of factors that could have been at play in the described situation is quite large, the general trend of misguided trust appears to be the key in the financial decisions made by Madoff’s investors.

However, it would be wrong to attribute all of the factors contributing to the effects of the scheme to gullibility of investors. Additionally, one has to consider the impact that regulatory oversight had on the effects of the fraud. Specifically, the lack of consistent and thorough audits cemented the success of Madoff affair and allowed its creators to continue brainwashing their participants into supplying finances for supporting the fraud. Overall, establishing tighter control over the management of financial processes is highly recommended as the tool for preventing the instances of fraudulence from taking place in the corporate setting.

References

Barner, C. (2012). Social media and communication. Sage.

Bosley, S. A., Bellemare, M. F., Umwali, L., & York, J. (2019). Decision-making and vulnerability in a pyramid scheme fraud. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 80, 1-13. Web.

Brownlie, D. (2012). Andragogy. Web.

Cummings, J. N., Butler, B., & Kraut, R. (2014). The quality of online social relationships. Communications of the ACM, 45(7), 103–108. Web.

Gurun, U. G., Stoffman, N., & Yonker, S. E. (2018). Trust busting: The effect of fraud on investor behavior. The Review of Financial Studies, 31(4), 1341-1376. Web.

Hidajat, T. (2018). Retracted: Financial Literacy, Ponzi and Pyramid Scheme in Indonesia. JDM (Jurnal Dinamika Manajemen), 9(2), 198-205. Web.

Mohammadi, A., & Shafi, K. (2018). Gender differences in the contribution patterns of equity-crowdfunding investors. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 275-287. Web.

Obamuyi, T. M., Iriobe, G. O., Afolabi, T. S., Akinbobola, A. D., Elumaro, A. J., Faloye, B. A.,… & Oni, A. O. (2018). Factors influencing Ponzi scheme participation in Nigeria. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(5), 1-11. Web.

Quisenberry, W. L. (2017). Ponzi of all Ponzis: critical analysis of the Bernie Madoff scheme. International Journal of Econometrics and Financial Management, 5(1), 1-6.

Rastuti, T., & Pharmacista, G. (2019). The application of the principle of utmost good faith in pyramid scheme business practice. Journal Sampurasun: Interdisciplinary Studies for Cultural Heritage, 5(1), 53-61. Web.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (n.d.). Pyramid schemes. Web.