Executive Summary

The credit crisis has negative impacts on the financial market liquidity. Such effects can be studied through analysis and evaluation of the implications of a case of the financial crisis experienced by a nation. This paper deploys the case of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis to discuss the effects of any financial crisis on market liquidity. Since the 1930s, the 2007-2008 global financial crisis encompassed the largest shock to global financial systems. Consequently, while looking forward to mitigating the reoccurrence of the recent global financial crisis, the question of the relationship between credit crisis and liquidity risk remains important. The world financial system encountered an urgent demand from short-term creditors and the existing borrowers among other sources of credit pressures. The repercussion was the falling credit, which hit the banking systems in a hard way. The lending programs for central banks intervened to mitigate the sharp decline in credit lending and reduce the raising liquidity pressures. This paper confirms that it is necessary to regulate the liquidity of banks to strengthen their resilience to credit risks so that credit becomes less vulnerable to various financial shocks.

Introduction

The 2007-2008 global financial crisis marked a defining moment of the US and other developed nations’ economic business cycle. The catastrophe began in 2007 following a housing slump. Later, it grew to affect global economies during late 2007. Nations such as the UK encountered credit crunch repercussions through the financial crisis that resulted in the collapsing of businesses and the erosion of consumer confidence during winter. In Jordan, although the banking sector was not affected, commodity prices rose due to the high dependence on oil in production processes. On the global scale, the damage was done to economies and their prospects were irreversible. The crisis increased the susceptibility of economic systems to credit risks. This form encompasses the investor-perceived risks that accrue from the failure of borrowers to make payments as agreed. Precisely credit risks accrue from the perception of losing or even actual loss of the principal amount when borrowers fail to repay loans extended to them by financial institutions. When such risks occur, creditors fail to meet their contractual obligations with lenders. This paper claims that credit crisis such as the recent global financial calamity has the effect of increasing the vulnerability of global credit financial systems to liquidity shocks, which impair their market liquidity.

Literature Review

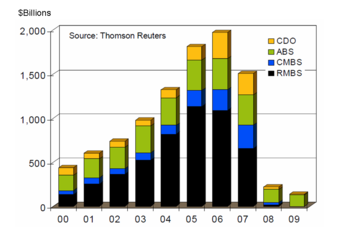

Credit crises lower the financial market liquidity. In fact, credit crisis risks have negative ramifications on the market liquidity. Some structures of a financial organisation may collapse entirely upon the occurrence of a financial crisis. For instance, as depicted in figure 1, the 2007-2008 global financial crisis affected severely the US securitization markets. The term liquidity crisis implies the drying up or sharp shortage of liquidity. According to Stange and Kaserer (2011), the word may imply market liquidity, funding liquidity, or liquidity trades among other related terms. Market liquidity means the ease with which an investor can convert assets into a liquid medium such as cash (Stange & Kaserer, 2011). Funding liquidity implies the degree of easiness to which one can acquire external funding from an outdoor lender such as a bank. Liquidity trade means lenience of selling securities by investors in the quest to obtain urgent cash. These different forms of liquidity reinforce each other during a credit crisis (Stange & Kaserer, 2011).

A credit crisis decreases market liquidity when financial organizations reduce their lending activities to avoid credit risks. Even though the monetary crisis compels financial organizations to reduce lending activities out of the need to minimize the level of risk that is associated with default, financial regulators compel them to reduce their lending activities. The regulators increase the policies on lending requirements. Through their study on the implication of capital constraints and the tightened liquidity on the capacity of various banks to lend, Barajas, Chami, Cosimano, and Hakura (2010) assert that capital constraints provide more effects on the ability of a bank to lend compared to the stiffened liquidity during the 2007-2008 global financial crisis.

Financial organizations offer liquidity to creditors and/or depositors by putting in place programs for giving money on demand. Liquidity risk arises from the outflows in deposits together with the process of lending between banks and the associated financial arrangements (Barajas et al., 2010). Such arrangements include commitments that involve undrawn loans and the requirements to acquire securitized assets.

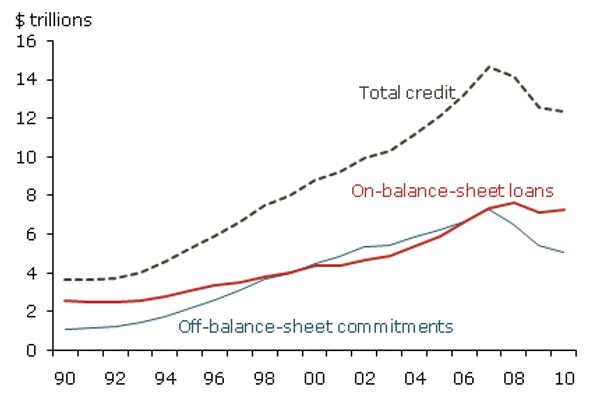

Banks lend money by developing credit lines that people use to borrow funds. When borrowers take advantage of the available credit commitments, banks are exposed to higher financial risks. In fact, the falling liquidity supplies compel borrowers to draw money massively in the form of credit from accessible credit lines (Eken, Selimler, & Kale, 2012). During the 2007 to 2008 financial crisis, the non-financial sector organizations had no access to short-term loans upon the drying up of the commercial paper market. People who utilized commercial paper resorted to prearranged credit lines from the bank to help them finance their paper whenever it was necessary. Since banks had the obligation to fund the loans, funds that were available for lending became incredibly limited. Therefore, the easiness with which people could convert their assets into cash was reduced due to the declining availability of cash on demand.

The drying up of the market liquidity during the credit crisis is a phenomenon that has been documented with supporting evidence by economic scholars. The phenomenon may have partially contributed to the 2007-2008 financial contagion. Guided by this line of thought, Brunnermeier and Pedersen (2009) provide an explanation of liquidity spirals by establishing a relationship between the spirals and market liquidity. The researchers note that a decline in the market has a negative repercussion on asset traders. This situation increases the margin call likelihood. Using various liquidity measures, Liu (2006) demonstrates that the US stock market’s liquidity is affected by credit crises such as the 1972-1974 recession. Yeyati, Schmukler, and Van Horen (2008) contend with this argument by claiming that the credit crisis has a negative effect on market liquidity in emerging markets. Focusing on such markets and deploying 52 stocks drawn from seven different nations as samples, the researchers argue that from 1994 to 2004, the crisis period increased the liquidity costs and trading activities that then reduced over the later stages of the crisis (Yeyati et al., 2008).

Naes, Skjeltorp, and Ödegaard (2011) adopt a general view and interpretation of the effects of economic cycles on market liquidity. In particular, they note that market liquidity sharply declines during economic downturns. They support their arguments using the NYSE shares traded between 1994 and 2008 together with Oslo stock exchange samples of 1980-2008. Naes et al. (2011) suggest that market liquidity varies depending on the economic cycle experienced in a given nation but is worse negatively impacted by credit crisis associated with a decline in markets. Consequently, liquidity costs and market returns have a negative relationship with market downturn cycles. Indeed, Brunnermeier and Pedersen (2009) suggest that a crucial transmission avenue for market liquidity for market downturns involves liquidity commonality together with flight-to-liquidity approaches.

The arguments developed so far imply that a reduction of the lenience of converting assets into liquid forms such as cash (market liquidity) results from the credit crisis. However, a scholarly question of interest concerns whether market liquidity can propel a credit crisis. In fact, although many economic scholars consider the losses in mortgages possible causes of the crisis, different theories have been advanced to explain the root of the 2008 global financial crisis. For instance, Adelson (2013) asserts that losses in mortgages are too minute to provide a sufficient explanation of the credit crisis. The 2013 mortgage losses realized together with those that were not yet realized by then were approximately $750 billion to about $2 trillion. However, depending on measurement methodology, the total losses due to the crisis ranged between $5 trillion and $15 trillion (Adelson, 2013). This finding suggests that losses in mortgages only served as an important trigger of the financial crisis. Hence, market liquidity losses may not sufficiently explain the occurrence of a credit crisis.

Liang (2012) attributes the root of the credit crisis to financial globalization, which creates imbalances in real-exchange adjustments. In this process, the US has the responsibility of managing financial risks and global liquidity. However, it failed to offer crucial banking services (Liang, 2012). This situation heralded the 2008 financial crisis. Adelson (2013) adds that issues such as excessive securitization, the 30-year deregulation trends, the propagation of the culture of taking risks within the American financial industry, and globalization explain the root of the 2008 financial crisis. Therefore, the failure to effectively manage financial risks, including those posed by liquidity, securitization, and deleveraging potentially explains the critical causes of the 2008 global financial crisis. Thus, the failure to manage financial risks led to the crisis, which then reduced the easiness with which investors could convert their assets into cash. Drawing from the discussions of this section, the credit crisis heralds a decline in market liquidity. Using the case of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, the next section analyzes and discusses this assertion.

Discussion and Analysis

The case of the European Union (EU) financial institutions exemplifies how the credit crisis increases liquidity risks. Financial organizations in the European Union get finances from surplus spending units, namely SSUs and then give it to deficits spending units. SSUs place their funds in the banks with the hope of securing a fixed rate of return on their savings. They also anticipate being immune from various investment risks. Eken et al. (2012) assert that DSUs make efforts to borrow money from the banking industry to fix costs that are associated with their borrowings. They also aim at protecting themselves from potential risks that arise from an imminent financial crisis. Such an effort is crucial in helping the DSUs and SSUs to deal with financial uncertainties. During the global financial crisis, SSUs and DSUs push banks to assume unwanted risks in the EU banking system. The available credit for lending dried up such that it became difficult for financial institutions to borrow money from SSUs.

Credit crises such as the 2007-2008 global financial predicament exposed banks to major threats in their effort to mitigate risks and/or increase their profitability and market value. However, it is important to note that the financial crisis influenced different economic systems differently depending on their risk resilience capacities. Sensitivity and volatility constitute the building blocks of financial risks. Threat-prone financial institutions have high levels of sensitivity and low levels of volatility. Hence, during the credit crisis, threat-prone banks are negatively affected seriously in comparison with threat-averse banks.

The global financial crisis resulted in the rising up volatility levels. This situation had the impact of shrinking investors’ preferences (Eken et al., 2012). In such situations, risk-prone investors also make strategic decisions to deploy risk-averse strategies in the effort to minimize the exposure to non-financial and financial risks. Directly congruent with this assertion, De Haas and Van Horen (2011) assert that a financial crisis forces economic-financial systems to raise their efforts to conduct thorough scrutiny of the borrowers to ensure they eliminate the risks of loan default. Ivashina and Scharfstein (2010) support this line of argument by adding that during a credit crisis, banks reduce their lending activities. For instance, during the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, the largest lending decline was witnessed in banks that had low accessibility to financial deposits. A reduction of lending activities implies that investors have low funding and trade liquidity.

Credit crisis increases the non-financial organizations’ liquidity demand. For example, the 2007 to 2008 credit crunch forced many business organizations in the US to draw funds from their prevailing credit lines because they feared potential credit market disturbances (Eken et al., 2012). This concern made the American Electric Power Company withdraw 2 billion US dollars from the credit lines of JP Morgan and Barclays. This strategy was taken to ensure that the utility’s cash position was improved in the fear of credit market disturbances (Ivashina & Scharfstein, 2010) as the crisis progressed. Consistent with the discussion in the literature review, this implies that the credit crisis implies reducing available cash for lending to investors and people wishing to purchase assets. Therefore, the easiness of converting assets into cash (market liquidity) reduces. This scenario is evidenced by the fact that when the electric power company withdrew 2 billion US dollars from the credit lines of JP Morgan and Barclays, it meant that the banks did not have sufficient cash for lending to those who wished to purchase assets.

Financial institutions finance their balance sheets in different ways. The most important ways include equity capital and deposits. Other alternatives include the wholesale of uncovered deposits and the reacquisition of unprotected agreements and instruments. During credit crises such as 2007 to 2008 global financial catastrophe, these interventions become limited. For instance, reports are used in financing risky assets, the classified brand credit-backed securities (Eken et al., 2012). By mid-2007, Gorton and Mentrick (2011) inform that these securities were possible to fund through short-term loans acquired from the repos.

Following the global financial crisis, the above approach changed so that by the end of 2008, only about 55 per cent of all such securities were possible to fund from repos. Consequently, financial organizations that deployed repos in financing them encountered unattractive choices (Eken et al., 2012). Hence, they suffered huge losses since the only available option was to sell securities in a collapsing financial market. The money that could be circulated to people from the sale of repos by financial organizations was reduced such that funds were not enough to purchase assets. Thus, consistent with the discussion in a literature review, a credit crisis has the effect of lowering market liquidity. Figure 1 below depicts the impact of the liquidity risks on the US financial organizations.

From the context of traditional liquidity frameworks, liquidity risks emanated from bank operations where people withdrew in en masse their deposits due to the raising mistrust of such institutions in a situation of amplifying financial hardships. These runs increased the possibility of the banks becoming insolvent. This risk was kept in check by requiring tying deposits to reserve requirements through strategies such as deposit insurance and availing central banks’ liquidity as the last option available to commercial banks. In the more recent economic environment, liquidity risks emanate from interbank arrangements and various lending activities, as opposed to depositing outflows. Ivashina and Scharfstein (2010) identify some of the risks as the commitment of undrawn loans and the obligation of buying securitized assets. For instance, banks and other financial institutions offer credit lines from which borrowers tap when they need cash while making various loan commitments.

The rising number of borrowers who utilize credit commitments increases the banks’ credit risks. Indeed, the falling liquidity compels people to use the available credit lines in large numbers. For instance, during the 2007-2008 global credit crisis, various non-financial organizations lost accessibility to the available short-term cash following the drying up of the commercial paper. Issuers of commercial papers resorted to prearranged backups with banks to re-finance the commercial papers when they became due. Consequently, the banks were to meet their obligations of financing the loans. This situation led to even more deterioration of new lending lines. Hence, market liquidity was even worsened due to the dwindling new lending lines. Therefore, it is apparent that any credit crisis impairs market liquidity by increasing the obligation of financial organizations to meet their prearranged agreements with other financial institutions.

Conclusion

Financial institutions such as banks play a critical role in ensuring market liquidity. They accomplish this role by availing cash when demanded by depositors and creditors. The cash can then be utilized to purchase assets. Therefore, when one intends to convert assets into cash, financial institutions supply cash to the creditors or depositors. In turn, they use it to acquire assets from those who deposit capital or willing to convert the assets into cash. Hence, through lending, banks increase the degree to which people can translate assets into cash. However, during a credit crisis, credit lines from which depositors and creditors can tap dry up so that banks are unable to provide cash on demand through lending. The paper has argued that a credit crisis such as the one experienced in 2007-2008, has a negative impact on market liquidity, especially in developed economies, for instance, the United States. Therefore, during the crisis, people experience a reduced capacity to convert their assets into cash.

Reference List

Adelson, M. (2013). The Deeper Causes of The Financial Crisis: Mortgages Alone Cannot Explain It. Journal of Portfolio Management, 39(3), 16-31.

Barajas, A., Chami, R., Cosimano, T., & Hakura, D. (2010). U.S. Bank Behavior in the Wake of the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis. London: IMF Working Paper.

Brunnermeier, K., & Pedersen, H. (2009). Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Review of Financial Studies, 22(6), 2201–2238.

Cornett, M., McNutt, J., Strahan, P., & Tehranian, H. (2011). Liquidity Risk Management and Credit Supply in the Financial Crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(2), 297–312.

De Haas, R., & Van Horen, N. (2011). Running for the Exit: International Banks’ and Crisis Transmission. London: EBRD Working Paper.

Eken, M., Selimler, H., & Kale, S. (2012). The Effects of Global Financial Crisis on the Behavior of the European Banks: A Risks and Profitability Analysis Approach. ACRN Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives, 1(2), 17-42.

Gorton, G., & Metrick, A. (2011). Securitized Banking and the Run on the Repo. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(3), 425–451.

Ivashina, V., & Scharfstein, D. (2010). Bank Lending During the Financial Crisis of 2008. Journal of Financial Economics, 97(11), 319-338.

Liang, Y. (2012). Global Imbalances and Financial Crisis: Financial Globalization as a Common Cause. Journal of Economic Issues, 16(2), 353-362.

Liu, W. (2006). A liquidity-augmented capital asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 82(3), 631–671.

Naes, R., Skjeltorp, A, & Ödegaard, B. (2011). Stock market liquidity and the business cycle. The Journal of Finance, 66(1), 139–176.

Stange, S., & Kaserer, C. (2011). The impact of liquidity risk: A fresh look. International Review of Finance, 11(3), 269–301.

Yeyati, E., Schmukler, L., & Van Horen, N. (2008). Emerging market liquidity and crises. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(2-3), 668–682.