Introduction

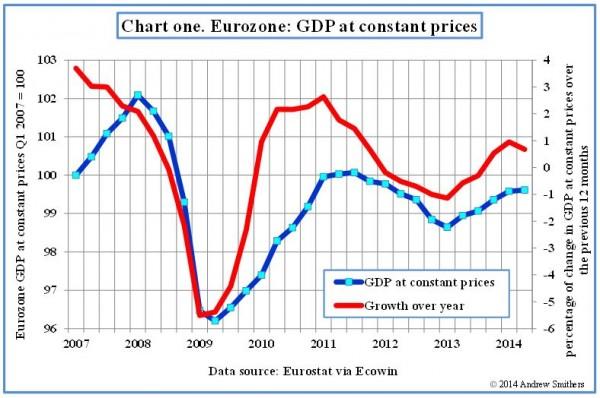

The European Union (EU) is facing ongoing economic challenges occasioned by stagnating economic growth and the euro-zone debt crisis. Since the economic recession of 2007-2008, the EU’s economic growth has been gradual, and it is projected to reach less than one per cent (Smithers n.pag.). Compared to previous years, there is a pattern of stagnation in the euro area’s economic progress since 2009 (refer to figure 1). The same conditions have been reported elsewhere in the world considering that the current World Economic Outlook (WEO) shows that the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in different global economies will change at a sluggish pace. Apart from the deepening economic crisis, the EU is suffering high rates of unemployment and public confidence in a near-future economic recovery is worsening (Lorca-Susino 28).

Based on the foregoing issues, economic experts recommend that the European Central Bank (ECB) and individual governments of the EU should take necessary steps to improve the region’s economic performance (Lorca-Susino 30). More specifically, in a recent Eurobarometer survey of 2011, many respondents from different EU countries observed that the euro had done little to lessen the negative consequences of the economic crisis. On the other hand, the Eurobarometer survey found that many Europeans seem to agree that individual governments in the EU should seek ways of lowering public debt and deficits to improve the performance of their economies (refer to figure 2). Furthermore, many European and non-European experts propose that the ECB should expand its role in lending by purchasing the European sovereign debts to address the ongoing debt crisis. In other terms, the experts suggest that the ECB should implement the quantitative easing (QE) policy in resolving the current economic crisis in the euro-zone (Tempelman 4). This paper explains how the ECB seeks to implement the QE policy by examining its goals and intended impact as well as its economic risks. In addition, the paper recommends appropriate ways through which the ECB can address the ongoing economic crisis.

Quantitative Easing (QE) in the European Union (EU)

Quantitative easing (QE) is a non-conventional macroeconomic policy used by central banks to purchase national debt securities from troubled countries to increase their market liquidity. Moreover, QE involves increasing the supply of money into the market to enable banks to implement lower interest rates and other related monetary policies (Lu 341). Quantitative easing is an unpopular monetary policy in contemporary economics. Nonetheless, the policy has received a lot of attention since the beginning of the economic downpour of 2007-2008. Central bank institutions of different economies such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan have used QE in recent years to reduce the consequences of prolonged economic declines (Tempelman 4).

During an economic recession, it is common for the central bank of a given country to implement different economic policies to stimulate economic recovery and growth. One such policy may involve decreasing the interest rates charged by banks to as low as zero per cent. However, the implementation of lower interest rates and other common interest-rate interventions does not always bring an immediate end to economic recession. Therefore, when an economic recession persists, the only other option is for the central bank to make more money available in the market to prevent subsequent economic declines (Lu 342). Based on the foregoing, it will appear that, QE is a last-minute monetary policy that should be used only when other options have been exhausted.

Different countries in the European Union, just like their international peers, have been struggling with a sluggish economy since the economic recession of 2007-2008. In response to the ongoing economic crisis in the euro-zone, the European Central Bank (ECB) embarked on the process of stimulating economic recovery by increasing the amount of liquidity in the financial markets across different member countries, such as Greece, Italy, and Spain (Lorca-Susino 32). However, the revival of the financial system has not yet cushioned the residents of the EU against the consequences of the ongoing economic crisis. Accordingly, many EU and non-EU economists have for long been calling for the implementation of the QE policy by the ECB to prevent more economic declines. In turn, the ECB plans to inject more money into the EU markets by increasing its balance sheet to almost €1trillion (Munchau n.pag.).

By injecting more money into the market, the ECB has agreed to implement the QE policy. In essence, the ECB’s quantitative easing policy aims to decrease the interest rates charged by individual banks in the euro-zone. Specifically, the ECB will purchase government bonds whose yield will decrease subsequently; and theoretically, the interest rates will also decrease, especially for banknotes. Furthermore, the ECB may decide to follow the “portfolio rebalancing channel” by purchasing bonds from banks, which may in turn finance the purchase of risky securities; hence, injecting more money into the economy. Finally, the ECB might follow the more effective channel of QE, which is to purchase and retire member country’s national debts to ensure that more money is available for economic development (Lorca-Susino 34; Munchau n.pag.).

As stated earlier, different countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan have previously used the QE policy; and the results look promising. However, the implementation of the QE policy in the euro-zone might be unsuccessful due to various shortcomings and economic risks. For instance, the use of the QE policy by the ECB or any other country’s central bank may potentially lead to an increase in inflation in the long-run. Specifically, when a central bank injects more money into the financial markets by purchasing the assets held by banks, it means that the extra money must be drawn from the market when the economy begins to recover and prevent inflation. However, it appears that the ECB lacks the necessary tools to unload the excess reserves in the market when the economy of the EU starts to flourish (Tempelman 4).

This is particularly relevant considering that even in the United States and the United Kingdom whereby the QE policy has been used; many economists are still waiting to see its impact on inflation at the end of the economic recession. Furthermore, the purchase of sovereign debts from countries with high credit risk may mean that the same risk will be transferred to the ECB and eventually to all European taxpayers (Schafer 188). Similarly, the implementation of the QE policy in the euro-zone may undermine the ECB’s function as “a bank of last resort” and turn it into an institution that carries the burden of insolvent banks and governments (Tempelman 4).

Recommendations and Conclusion

Evidently, the foregoing discussions show that the ECB has made several steps towards stimulating economic growth in the EU. However, most of the previous interventions by the ECB have done little to resolve the ongoing economic crisis in the euro-zone. For instance, through the Long Term Refinancing Operation (LTRO) mentioned earlier, the ECB has previously used a policy of lending money to financial systems at an interest rate of as low as one per cent (Lorca-Susino 34). In turn, the banks have been given more money to purchase sovereign debts from EU countries that face major financial problems. This, in principle, is a form of quantitative easing, but it has not been fully executed because Article 123 of the European Union prohibits the ECB from using such monetary policies. This shows that the ECB is operating within a limited space in its efforts towards ensuring that troubled countries are adequately financed to pull out of recession.

Accordingly, it is hereby recommended that the member states that form the ECB should dialogue and seek a middle-ground on the best possible way of using QE to stimulate economic growth in the euro-zone. This is because it appears that the only way that the ECB can stimulate significant economic growth in the euro-zone is by injecting more money into the economy. The abovementioned difficulties withstanding, the bank still has more options to choose from before embarking on quantitative easing as a last resort. On one hand, the member states of the EU should consider introducing Eurobonds, and on the other hand, the ECB should be allowed to purchase an unlimited number of bonds from troubled countries in the EU. Similarly, the EU should consider introducing effective debt restructuring policies in troubled countries to ensure that the ECB finances struggling institutions out of the ongoing economic crisis (Schafer 189-191).

Works Cited

Lorca-Susino, Maria. “The Eurozone and the Economic Crisis: An Innovative SWOT Analysis.” Economics, Management, and Financial Markets 9.2 (2014): 27-40. Print.

Lu, Yingxi. “Quantitative Easing: Reflections on Practice and Theory.” World Review of Political Economy 4.3 (2013): 341-356. Print.

Munchau, Wolfgang. “The ECB, Demigods and Eurozone Quantitative Easing.” The Financial Times. The Financial Times Ltd. 2014. Web.

Schafer, Hans-Bernd. “The Sovereign Debt Crisis in Europe, Save Banks Not States.” The European Journal of Comparative Economics 9.2 (2012): 180-195. Print.

Smithers, Andrew. “The Eurozone and Quantitative Easing.” The Financial Times. The Financial Times Ltd. 2014. Web.

Tempelman, Jerry. “Against Quantitative Easing by the European Central Bank.” Financial Analysts Journal 1.2 (2012): 4-6. Print.