Abstract

Leadership is present everywhere in the organizational structure, starting with the CEO through mid-level management and to the daily organization of operations by low-level workers. Effective leadership provides a change framework, including developing a vision, setting goals, influencing followers to work toward these objectives, and communicating clearly and efficiently. This essay selectively reviews leadership theories that try to conceptualize different types of leadership and the methods by which one can apply them. The paper focuses on transformational theory, which scholars have associated with outstanding results and which I personally prefer. Among other covered theories are authentic and distributed leadership, both of which aim to maximize worker satisfaction and well-being in different ways. Two leaders I have worked under are analyzed using these theories, including vision articulation, communication, follower inclusion and autonomy, and influence on personal identification. Overall, I have settled on three leadership styles I will aim to learn and use in practice, and each requires me to improve in specific aspects of personal conduct and skills. Having understood these requirements, I have committed to improving myself as I practice leadership and adopting them to improve my effectiveness.

Introduction

Recently, leadership research has focused on followers and motivating them to excel and support the organization as a key driver of efficiency and success. Leadership is among the most investigated topics in organization management (Antonakis & House, 2014, p. 149). It is commonly defined as personal influence, which is used to drive followers towards fulfilling organizational goals through a variety of incentives (Schyns & Schilling, 2013, p. 138). The definition implies that employees maximize productivity, including support towards company objectives, under the influence of competent leaders. The role is responsible for driving change and supporting operations to achieve that goal. Leaders play social roles in persuading employees to align their interests to those of the company. With that said, leadership is highly personal and unique, and scholars have been working to categorize successful models into different types. This paper aims to review leadership models to explain how leaders exercise control in organizations and evaluate specific leaders’ behaviors. The findings are used to reflect on the author’s knowledge and learning and identify areas for improvement.

Critical Review on Leadership Theories

Autocratic Leadership

Under the autocratic leadership style, the leader holds exclusive authority over decision-making in the organization. They make choices based on the information available to them and require their followers to comply unconditionally. As possibly the simplest leadership style, this approach had emerged before any theories were developed, likely before the beginning of recorded history. The autocratic leadership style has a number of advantages with regard to aligning the organization and ensuring that it operates smoothly. A leader that follows this theory understands that organization members will often have conflicting interests but will not be paralyzed by trying to satisfy all of them (Meyer & Meijers, 2017). When necessary, they can use their authority to remove inefficiency or resolve indecision, making the organization function smoothly and quickly. A sufficiently capable and charismatic autocratic leader can encourage employees to focus on their tasks and rely on them.

With that said, throughout most of the world, the autocratic leadership style is being phased out as outdated due to its numerous issues. It lacks a focus on the human element in the organization, as it is easier for the sole decisionmaker to conceptualize it as a rigid system (Halaychik, 2016). As a result, it is easier for them to focus on the role than the person occupying it, which leads the followers to feel underappreciated. Moreover, communication is also hindered because workers may not feel encouraged to offer feedback, especially if it is negative. Ultimately, workers are more likely to leave an autocratic leader’s team, even if they personally benefit from the sty (Van Vugt et al., 2004) l e. As such, most organizations have transferred from this leadership approach as work culture developed.

Laissez-Faire Leadership

Laissez-faire leadership is generally considered the opposite of autocratic leadership, both in concept and in execution. In it, the leader lets the followers have absolute autonomy and rarely, if ever, interferes. This style likely also predates contemporary leadership research, as it describes any organization whose leader is absent. In its advantages, it is similar to the distributed leadership style described below, as it drives followers to deliver leadership skills and increases their ownership of the organization’s mission. As a result, workers grow faster and develop new competencies, becoming more creative and accustomed to taking the initiative (Domfeh-Boateng & Imhangbe, 2019). With that said, this growth is driven not by the opportunities given to the workers but rather by necessity. As a result, the laissez-faire approach also has a number of limitations that prevent its widespread usage.

The first and foremost problem is the need for workers to adapt to workloads to which they are not used on short notice. In the absence of a leader, the successful performance or a failure of the organization depend on them. This burden leads to the natural accumulation of stress, which the leader’s non-involvement does not help offload, possibly leading to worker burnout (Diebig & Bormann, 2020). Another issue with the leader’s absence is that, as in the case of autocratic leadership, workers do not offer feedback or other forms of upward communication. Where for authoritarian leaders, they expect to be ignored or overruled, for laissez-faire superiors, the perception is that they will simply refer the problem back to the lower level (Agodu, 2019). As a result, issues that are beyond the employees’ ability to address will develop under this leadership style and possibly cause considerable harm.

Transactional Leadership

Transactional leadership is among the most commonly adopted leadership styles today, owing both to its effectiveness and the simplicity of its application. It consists of the creation of a mutual relationship between the leader and the followers, where the latter deliver results and the former applies rewards or corrective action based on whether the outcomes are satisfactory (Vigoda-Gadot & Drory, 2016). The chief advantage of this leadership style is in its clarity; clear metrics are set, and both sides understand what is expected of them. As such, there is minimal confusion, and ambitious workers can apply themselves to advance. Moreover, transactional leadership incorporates feedback, and followers explicitly negotiate objectives and rewards with the leader until a mutual agreement is reached (Arenas, 2019). These discussions involve analysis of the company’s capabilities and objectives, leaving both sides with a more complete picture of the events that are taking place.

The clarity in the leader-follower relationship, as well as the ability to set reasonable goals and meet them, contribute to the popularity and success of transactional leadership. However, it also has numerous issues, many of which stem from its rigid nature. Under it, followers are incentivized to follow current practices to meet targets instead of taking risks to innovate, which can harm the organization in the long term (Akkaya, 2020). As a result, they will also struggle to develop new skills, as their preset targets do not call for doing so. Employee motivation also suffers, and if they find a shortcut to achieving the objectives on paper with minimal effort, they are likely to take it. Acknowledging these issues but also recognizing the style’s effectiveness, many organizations train their leaders in it as a secondary approach to specific situations (Moone, 2017). It supplies a structure that can be used to achieve goals, while other approaches help manage followers better.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is a relatively new concept, having been introduced in its current form by Bernard M. Bass in 1985. Since then, it has gone on to deliver measurable improvements to organizational performance across different companies and find widespread adoption (Seltzer & Bass, 1990). Unlike many of the earlier leadership styles, it focuses explicitly on the followers, driving them to improve themselves for the sake of contributing to the organization. Under this approach, the leader becomes a focal point that serves as a reference for their followers’ self-improvement under what is known as idealized influence (Malhotra & Axelsen, 2018). As a result, they see and follow the leader’s vision for the organization, recognizing necessary aspects of self-improvement and addressing them with the superior’s aid. The ultimate result is a comprehensive improvement in performance and a more capable team that is committed to the organization’s goals.

Studies show that the transformational leadership approach enables leaders to stand out in terms of organizational performance (Schyns & Schilling, 2013, p. 144). It is a broadly researched topic that has shown consistent performance improvements in most environments where it was applied. Transformational leadership consists of developing visions to direct and motivate followers while effectively engaging others and providing “a sense of meaning” (Schyns & Schilling, 2013, p. 145). The definition highlights engagement as an important feature, encouraging leaders to actively involve followers in their messaging and retain attention. Transformational leaders influence others through role modeling, becoming examples for others to be inspired by and follow. Collaboration is a key competence in leadership that attracts followers to understand and support leaders’ goals and the organizational vision (Ryan et al., 2009, p. 863). Involving followers in work structures creates trust, a vital element towards creating loyalty and inspiring subordinates to follow one (Ernst & Chrobot-Mason, 2011, p. 72). Trust towards leaders following followers’ engagement also increases productivity since group members are willing to listen to the leader whenever disagreements arise, which makes operations smoother. Followers also respond to the leader’s supportive and inclusive behaviors and reciprocate it, which can result in improved support during difficult periods.

Another essential characteristic of transformational leaders is their ability to impart a sense of meaning (Schyns & Schilling, 2013, p. 145). They motivate followers by helping them find the value of their work, which improves their self-esteem and satisfaction with the objectives they accomplish. The understanding of how one contributes to the company and how their work fits into the broader vision provides a different perspective and an incentive to support company goals and leaders to attain the shared goals (Covey, 2004, p. 106). Transformational leaders help followers develop internal motivation to enjoy their work and ensure that it has soft rewards in addition to the monetary compensation, such as a feeling of value in an organization and career development opportunities. Although an employee’s primary goal is income, they also like to see their contribution and to have self-perceived growth in their careers. These experiences influence satisfaction and motivation to support company goals to reap more benefits. Imparting a sense of meaning is a reward motivation since followers enjoy appreciation, inclusion, and career growth in addition to income. Human desires and the need for leadership have changed through biology and evolution towards favoring supportive leaders who can influence bonding, acquisition, and compression (Yammarino, 2013, p. 149). Followers are interested in leaders who can make them develop a strong relationship with their work by imparting meaning, for instance, through appreciation and training in transformational leadership.

With that said, transformational leadership also has noteworthy drawbacks that have prevented it from being adopted at every organization. The most significant one is the difficulty of doing so, as it is nebulous with regard to the specifics. The gaps have to be filled by the specific leader’s charisma, which cannot be mass-produced and would be disastrous if it could (Western, 2019). As such, many people in leadership positions simply cannot become transformational leaders and have to rely on other approaches for success. Additionally, this charisma may come with side effects on the leader’s personality, such as an inability to understand their or the organization’s limits. A somewhat common occurrence is for transformational leaders to set unreasonable deadlines or demand long working hours, leading to follower burnout (Lokendra, 2020). Lastly, the transformation takes some time to happen and does not produce quick results, so it is inappropriate in settings where swift change is required. Overall, transformational leadership is a powerful tool, but it is highly dependent on the specific leader in question and requires controls to be put in place.

Authentic Leadership

Authentic leadership is another approach that has been gaining scholarly attention recently due to its ability to produce desirable results. It has emerged recently as a response to various scandals that involved corporate misconduct due to unethical leadership (Northouse, 2019, p. 308). As a result, over time, the demand for leaders and related qualities have changed following the trends of past leaders through analyses of their biographies (Yammarino, 2013, p. 149). People are developing an increasing need to be able to trust their leaders and know that they are doing honest and productive work. Authentic leadership creates attachment and growth through openness, transparency, and employee development (Northouse, 2019, 308). The theory relates to transformational leadership, where leaders act as role models, but focuses more on behavior, which inspires workers to support the leader. Open and transparent leaders make it easy for employees to follow their actions since every action they take is easy to see and understand in the context of the company’s vision. Authentic leaders provide clear goals by stating objectives and pursuing them, inspiring others to follow them and contribute. They are accountable for their actions, which reinforces follower confidence in supporting these efforts as they can see and highlight any wrongdoing. Employees maximize their productivity and become transparent in supporting leaders that establish a culture of trust and openness.

Scholars in the field suggest that authentic leaders motivate followers through trust, oneness, and accountability. The leaders build authenticity through objective acceptance and approval of attributes and behaviors, leading to an authentic relationship with followers (Besen et al., 2017, 8). Authentic leaders establish and follow a well-defined set of practices and behaviors, which enables followers to guess what they would do and bring the leader’s image in their mind closer to the real person (Northouse, 2019, p. 310). These ethics attract followers who are ready to show accountability in their work and expect others to do the same. Contemporary workers increasingly value leaders who will create bonds and promote career development and growth (Yammarino, 2013, p. 149). The need to experience support from a leader motivates employees to adopt similar ethics, which will improve overall workplace accountability and align everyone toward the same goal. Authentic leaders inspire followers towards organizational goals by creating relationships based on honesty and openness. The recognition of an authentic leader is a reward for being honest and open towards the leader’s visions, and the understanding of that fact leads to enhanced productivity. The self-concepts and self-identities of authentic leaders are strong, clear, stable, and consistent (Yukl, 2012, p. 351). As a result, authentic leadership motivates followers by creating a two-way relationship of honesty, recognition, and respect between them and leaders.

Distributed Leadership

Another effective leadership approach is distributed theory, which scholars have also called collective and shared leadership due to its unique qualities (Feng et al., 2017, p. 2). Under the model, leadership functions, including decision-making and development of structures to achieve organizational objectives, are shared among the group rather than focused on a single person (Feng et al., 2017, p. 2). Distributed leadership creates an influence system based on joint action and interdependence. The model distinguishes leaders from managers and provides a framework for getting others to work on objectives without coercion. Unlike managers, leaders attract people who follow their vision, and the distribution of leadership among employees is a strategy to allow ownership of the process. This shared responsibility in leadership improves productivity and enhances the vision since followers behave like leaders and contribute their unique skills to the company’s cause. Employee inclusion in leadership influences their support towards organizational goals through shared responsibility (Fitzgerald et al., 2013, p. 228). Leaders who share their powers, such as decision-making, with followers, let them feel part of the goals and vision. The shared ideas influence a burden of accountability to the achievement of company objectives and team support. Distributing leadership shifts the position from being a follower to a leader, letting employees feel more involved in the company’s operations and contribute more actively.

The logical conclusion of distributed leadership is to question the importance of formal leaders, arguing that all workers would be supervisors (Günzel-Jensen et al., 2018, p. 111). As leaders progressively share their responsibilities with workers, they become less and less distinct from their followers. Followers in shared leadership become agencies to express their thoughts to shape experiences (Günzel-Jensen et al., 2018, p. 111). Decisions are made collectively through consultation, letting each worker contribute their knowledge and opinion. As a result, followers are exposed to the information they need to make the decisions and feel involved in the company’s vision and mission. Leaders using the framework are coordinators to combine ideas that lead to shared decisions. Distributed leadership leads to interrelationships between leaders and followers that influences outcomes positively (Fitzgerald et al., 2013, p. 228). The scholar demonstrates that leaders who share their powers with followers generate group interaction and responsibility-sharing. Similar to transformational leadership, the distributed model motivates employees through a sense of meaning where they own the process of structuring the workplace. The framework provides autonomy to employees and increases loyalty towards organizational goals and the leader’s vision (Unterrainer et al., 2017). Overall, distributed leadership can be a challenging model to follow, but it also enhances the decision-making process considerably if implemented correctly. It also guarantees worker commitment to the company and its goals, ensuring that their goals are aligned with the organization’s by design.

Evaluation of Leader Behaviors

Leader A

I have learned about leader A’s behaviors and leadership approach over more than ten years of working with company Y, of which he is the president. I had known company Y for several years before he became president, and it has maintained its status as a client since his taking the position. He previously worked for a U.S military organization, which is still identifiable in his mannerisms and overall behavior. My experience with leader A, including sharing and studying his performance record, enabled me to learn about his behaviors when he worked for the U.S military organization.

Among leader A’s traits I admire is his sharp ability to share and explain his vision to employees. When leader A was joining company Y, employees were scattered in their goals, pursuing personal benefits and promotions at each other’s expense and constantly undercutting each other, leading to group project failures. When he joined, he explained to workers that this attitude would no longer be tolerated and team failures will be counted as each individual member’s responsibility. His leadership has made employees focused, fostering a team approach towards a shared goal of success. The company’s performance has improved noticeably as a result, giving it the ability to win large-scale government awards. The ability to articulate a vision is among the distinguishing features between leaders and managers and allows idealized influence instead of coercion (Buchanan and Huczynski, 2019, 598). Leaders provide direction that brings all employees’ strengths and efforts together to achieve a common goal (Warren and Nanus, 2004, 65). This attitude is emphasized in leader A’s conduct, as he prefers having team rather than staff meetings where matters pertinent to current missions are discussed, and each member is encouraged to give their opinion. This focus is vital since it makes followers align their interest with that of a group as leader A did, leading to financial success.

Overall, I believe that leader A adheres well to the model of transactional leadership, though he does not exclusively follow it. Prior to his involvement, the employees were disorganized, pursuing personal benefits to the exception of the team goals or others’ success. He resolved that issue by realigning the reward system and tying it to team performance rather than individual achievement. In doing so, he exhibited the contingent reward aspect of transactional leadership, establishing clear expectations for followers and setting rewards that they would get for achieving those goals. His excellent communication skills are consistent with the description of leaders who align strongly with the practice (Poser, 2016). The improved company performance also aligns with findings that transactional leadership improves employee performance (Karaca & Demirtas, 2020). With that said, his ability to explain the company’s vision and motivate individual teams suggests that his leadership approach is not limited solely to this theory.

Leader A’s early behavior is consistent with autocratic leadership, as he came in and immediately started making sweeping changes at the company. He identified issues and started working to fix them, expecting his subordinates to keep up with his actions. Some of this tendency may be explained by his military background, where autocratic leadership is the norm due to the command structure. However, part of the reason for the choice may have been that transactional leadership is not necessarily applicable in situations that demand change, being better suited for stability (Poser, 2016). As such, leader A demonstrated flexibility and the capability to accomplish objectives swiftly when necessary, which are beneficial traits for a leader. Moreover, he was able to transition away from the autocratic style and win the employees’ trust, listening to their feedback and engaging in discussions.

The behavior of articulating vision with followers aligns with the transformational leadership approach to idealized influence, revealing A as an outstanding leader. Transformational leaders inspire followers to admire, trust and respect them based on their behavior and conduct, leading to shared goals and support (Northouse, 2019, 264). The interaction also relates with the transactional leadership model, where supervisors exchange behaviors with followers on the promise of future benefits through the proper articulation of vision (Hussain et al., 2017, 2). Similarly, sharing an idea with employees inspires followers to identify with the leader due to a clear direction that imparts responsibility and attachment to the organization. As a result, leader A’s behavior in developing and explaining vision and goals to employees is a decisive influencing factor towards employee support of organizational goals.

To effectively share his vision and explain to workers what he requires while also listening to their feedback, leader A has refined his communication skills. The leader’s success in the company comes in large part from his ability to establish proper communication structures to his followers, which minimize fear, lack of direction, and failed contribution of ideas from employees. Communication is a significant behavior in leadership since it supports influence through the exchange of information. Communication is an inspiration element in transformational leadership (Antonakis and House, 2014, p. 764). Transformational leaders inspire employees towards supporting a shared goal by communicating vision and other motivational complements. Communication provides shared meaning to the vision, consolidating employees’ interests, and highlights the path towards achieving goals, letting workers focus on the smaller details. Communication is also a vital element in authentic leadership. Authentic leaders show honesty and openness through clear communication of their feelings and motives. The leaders also motivate loyalty, respect, and support from followers through balanced processing, which results from the proper articulation of ideas after listening to different viewpoints (Northouse, 2019, 316). Leader A is a good listener to his followers while asking follow-up questions to have a clear glimpse of the different ideas presented before him. As a result, employees are less worried that their concerns are unaccounted for, which reduces fear and improves trust. Overall, A possesses good communication behavior that influences confidence, inspiration, and motivation towards the leader’s vision and organizational goals.

Lastly, it should be noted that leader A is neither laissez-faire nor a distributed leader. He has been actively involved with company Y’s operations ever since his appointment to the role of the president, and this commitment has never changed. While he does not micromanage operations at the low level, he keeps himself apprised of the state of different projects through the team meetings and offers feedback when he believes it is necessary. By the same token, while his employees have some degree of autonomy, they are still subject to oversight in a manner consistent with the description of passive management-by-exception, a component of transactional leadership (Poser, 2016). Leader A also does not exhibit distributed leadership, having explicitly created a hierarchy and assigned roles within the business. As a result, whenever there is a responsibility, there is also a specific person that can be contacted regarding it, which is antithetical to distributed leadership’s sharing thereof (Feng et al., 2017). Leader A’s refusal to adopt either of these styles may be explained through his military background, which, as mentioned above, rejects them both. Regardless, he is a highly effective leader who is capable of using multiple leadership styles successfully.

Leader B

The second leader is my current employer at company Z, with whom I have worked for over two years. I had known leader B for eight months before agreeing to sell my company to him in order to gain the ability to scale competitively. My work under leader B’s supervision has enabled me to learn about his leadership behaviors and develop a mostly negative opinion of them.

Leader B’s approach to leadership is charismatic, though he does not give employees a chance to articulate their issues and ideas or seek clarification about visions. Leader B considers himself to be a highly experienced and capable leader who is capable of making the right decision in any situation. In my first serious leader-follower discussion with leader B, he was talkative to the extent that I could not raise all my concerns and ask questions. Such an approach is inappropriate since it overemphasizes management and undervalues leadership. Ernst and Chrobot-Mason (2011, p. 72) describe leadership as a process of “forging a common ground” to influence followers through shared goals. Unlike managers, leaders control through information once they understand followers’ views to help them develop a shared vision and produce inspiration. Refusing to consider followers’ ideas is contrary to authentic leadership since such leaders do not honestly address and support followers leading to a lack of trust (Besen et al., 2017, 8). I have experienced low confidence towards leader B following his failure to empower his mid-level managers, express to employees that they are valued, and articulate his companies’ long-term goal other than generating revenue through whatever avenues are available. Authentic leaders create a positive involvement by being socially responsible. Leader B is not sensitive to his employees, a behavior that weakens his influence through subordinate mistrust.

Another of leader B’s behaviors is the provision of minimal autonomy among followers, leading to low empowerment and motivation. He insists on micromanaging matters and being involved at all levels of decision-making, often devoting inappropriate amounts of criticism to inconsequential matters. The leader lacks ethics such as post-conventional morality that requires an individual to decide based on a social contract on what is appropriate in society (Northouse, 2019, 490). Autonomy is essential in making employees feel like a part of the organization and motivation towards shared goals. Leader B’s behavior of limiting decision-making autonomy reduces his influence since employees now have to maneuver around his inevitable involvement instead of working for the company’s benefit. According to the leader-member exchange model, the dyadic relationship is the main focus of the leadership process (Naktiyok and Emirhan Kula, 2018, p. 122). Leaders negotiate roles, making followers members of an in-group to influence responsibility and accountability. However, the lack of autonomy in decision-making in leader B’s leadership approach implies the absence of negotiation where followers work on defined roles. The lack of freedom has made employees at company Z lose interest in developing a relationship with leader B because they do not expect anything positive to come from it, while keeping their distance may let them act autonomously on occasion. As a result, leader B is closer to a manager, directing employees through purely organizational means rather than communication.

Despite the negative behaviors, leader B is skilled at articulating an organizational vision that influences personal identification. My first encounter with leader B made me identify with his agenda, charisma, and motivation to take the company to greater heights. Leader B takes a considerable amount of time to show his followers that the company will grow significantly in the foreseeable future. Although he does not demonstrate how this will benefit followers, his description of company performance and development attracts workers to his ideas. Personal identification influences emotional bonds with a leader and results from the leader articulating their competency in delivering success (Zhang et al., 2016; Yukl, 2013, p. 312). Leader B’s behavior in influencing personal identification relates to ethical leadership, which attracts employees towards a shared vision and goals by demonstrating a positive future (Northouse, 2019, p. 495). Ethical leaders have values, vision, virtues, and a voice that allows follower inclusion. With that said, as outlined above, while leader B has one particular component of ethical leadership, he lacks the rest. As such, none of the theories discussed so far in this section describe him adequately.

Leader B demonstrates the classic traits of autocratic leadership, both positive and negative. Thereby, he rejects laissez-faire and distributed leadership by definition, and discussion of these two is not warranted. He makes decisions unilaterally and believes himself to be the best available expert on most, if not all, company-related matters. Over time, this approach has led the company to some success, enabling it to purchase my own. However, I believe that it is approaching its limits as the company grows and it is becoming increasingly challenging for him to micromanage every aspect of operations. As discussed above, he lacks interest in his employees, preferring to talk to them in a one-sided manner without listening to feedback. This behavior is indicative of a typical failing of autocratic leaders, as taking subordinates into consideration beyond the most basic level is mentally taxing and often not done (Halaychik, 2016). With that said, if he had solely relied on autocratic leadership, his business would have likely run into difficulties sooner.

Leader B cannot be said to be adept at transactional leadership, adopting small parts of it but not using the whole structure. Corrective action, usually in the form of a lecture and a personal intervention to “fix” the perceived problems, is applied to those who underperform. At the same time, those who achieve their objectives and more are not recognized, as leader B takes credit for their success and believes that they have merely followed his instructions correctly. As a result, negative reinforcement is present while the positive aspect is not, taking the worst aspects of transactional leadership with few of the benefits (Akkaya, 2020). These traits also disqualify leader B from being considered an authentic leader, as he does not have a specific and transparent set of principles. Lastly, due to his charisma, he may have the prerequisites for becoming a transformational leader (Western, 2019). However, his personality is likely not conducive for that, and he lacks the inclination to study how to become such a leader.

Summary of Lessons to Practice and Develop in Leadership

One of the lessons I have learned is that leaders should exhibit strong communication skills while manifesting empowerment-related traits. Unlike management, communication, both speaking and listening, is vital in leadership for the development of a motivated team with a shared vision. Collins (2001, p. 68) states that a leader should be a contributing team member and, therefore, needs skills and knowledge to effectively and successfully work with other people. Leadership theories also demonstrate that leaders’ critical role is to influence their teams towards common goals through clear communication of how and why they should pursue these targets (Javidan et al., 2010, p. 109). For instance, leaders use communication to inspire followers by communicating ideas, including painting a future picture in transformational leadership (Antonakis and House, 2014, p. 764). I will improve on my communication skills and practice them to become an effective and influential leader.

I will improve my communication skills through improvement in self-awareness. Goleman (2013, p. 51), writing for Harvard Business Review, states that focus on the self is a crucial fixture in emotional intelligence, which guides listening and speaking. A self-aware person understands their moods, emotions, and thinking patterns, which allows them to account for the effects of their state on their thinking and make rational decisions in most situations. I will develop my self-awareness, analyze my positive and negative responses to other people, reflect on how I respond to problems, understand issues that make me happy, and identify triggers that cause negative emotions.

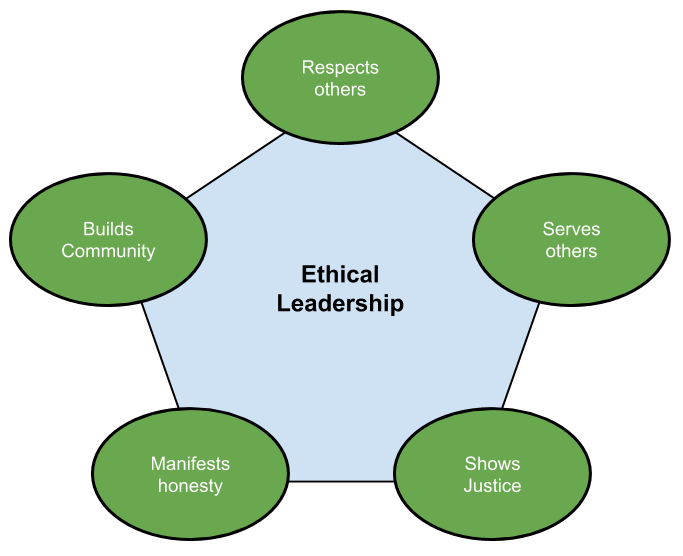

Another lesson from the review on leadership theories and behaviors is the value of ethics in influencing and motivating followers. The authentic leadership model demonstrates that trust is a significant feature in enabling one to effectively persuade and direct followers (Northouse, 2019, p. 308). Trust also applies in transformational and distributed leadership since workers would disagree with a disingenuous leader who tells lies about the future or emphasizes his self-interest above that of others or the organization. Ethics in leadership extend to providing followers autonomy and including them in decision-making, as the model of leadership ethics in the appendix shows. I have learned that ethical leadership influences and motivates followers to support the shared goals since they believe in their leader and feel supported.

By reviewing the two leaders in greater detail and applying different theories to explain their behaviors, I have been able to obtain some insights into myself. I do not believe that I have leader A’s commanding presence and ability to make changes quickly and decisively. Neither do I possess leader B’s charisma, and I believe that it will be challenging for me to develop either of these two skills. As such, I believe that it would be unproductive for me to pursue autocratic or transformational leadership effectively. With that said, I think that all of the other leadership styles mentioned in this paper are achievable for me. I do not consider the laissez-faire style useful and, therefore, have no plans for adopting it. As such, I am currently considering the transactional, authentic, and distributed leadership styles for adoption and usage whenever one or the other is more appropriate.

For transactional leadership, I will need to improve my communication skills and willingness to receive feedback. I will need to regularly negotiate with subordinates and determine reasonable expectations and rewards, which requires me to convey my ideas and listen to others (Arenas, 2019). A better understanding of company operations will also be necessary, but I expect that it will come as I engage in my managerial role and have subordinates address my misconceptions. Additionally, while I do not plan to pursue transformational leadership, I will still try to adopt aspects of it, such as the ability to communicate my and the company’s vision to the workers. It will help me motivate workers and explain to them why what they are doing is necessary.

As an authentic leader, I will need to become more transparent than I am currently and commit more strongly to my principles. Currently, I often act in my self-interest and take actions about which I am not proud in retrospect. In the moment, I justify them by necessity, but such conduct is unacceptable for an authentic leader because it may lead to misconduct and eventual scandals that undermine follower trust in their leaders (Northouse, 2019). I will need to align my words and my actions more closely, both in public when working with others and in private. In doing so, I will be able to become a person others can trust and an effective authentic leader.

For me to become effective in applying distributed leadership, I will need to understand the transition process and become more skilled at managing it. In its complete form, a distributed leadership model is self-sustaining, as each worker acts as a supervisor (Fitzgerald et al., 2013). However, they need to learn the necessary skills first, preferably in a safe environment where they can experiment and fail sometimes. As such, I will need to exhibit excellent leadership and take care of different responsibilities even as I slowly offload them to others. As such, the adoption of this style will need to wait until I am more competent in the other approaches and understand the particulars of leadership better. In the meantime, I will need to become better at delegation and less prone to micromanagement of the tasks I give others.

Reference List

Agodu, I., 2019. Leadership styles and companies’ success in innovation and job satisfaction: a correlational study. Bloomington: iUniverse.

Akkaya, B., 2020. Agile business leadership methods for Industry 4.0. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

Antonakis, J. & House, R., 2014. Instrumental leadership: measurement and extension of transformational-transactional leadership theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(4), pp. 746-771.

Arenas, F. J., 2019. A casebook of transformational and transactional leadership. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Besen, F., Tecchio, E. & Fialho, F., 2017. Authentic leadership and knowledge management. Gestao and Producao, pp. 2-15.

Buchanan, D. & Huczynski, A., 2019. Organizational behavior. Pearson Education.

Collins, J., 2001. Level 5 leadership-the triumph of humanity and fierce resolve. Harvard Business Review, January, pp. 67-76.

Covey, S., 2004. The 7 habits of highly effective people: powerful lessons in personal change. s.l.:Simon and Schuster.

Diebig, M. & Bormann, K. C., 2020. The dynamic relationship between laissez-faire leadership and day-level stress: a role theory perspective. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(3), pp. 324-344.

Domfeh-Boateng, J. & Imhangbe, O. S., 2019. The essentials of leadership. Christian Faith Publishing.

Ernst, C. & Chrobot-Mason, D., 2011. Boundary spanning leadership: six practices for solving problems, driving innovation and transforming organizations. McGraw Hill.

Feng, Y., Hao, B., Iles, P. & Brown, N., 2017. Rethinking distributed leadership: dimensions, antecendents and team effectiveness. Leadership and Organizational Development, July, 38(2), pp. 1-31.

Fitzgerald, L., Ferlie, E., McGivern, G. & Buchanan, D., 2013. Distributed leadership patterns and service improvement: evidence and argument from English healthcare. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), pp. 227-239.

Goleman, D., 2013. The focused leader. Harvard Business Review, pp. 50-60.

Gunzel-Jensen, F., Jain, A. & Kjeldsen, A., 2018. Distributed leadership in heathcare: role of formal leadership styles and organizational efficacy. Leadership, 14(1), pp. 110-133.

Halaychik, C. S., 2016. Lessons in library leadership: a primer for library managers and unit leaders. Cambridge: Elsevier.

Hussain, S., Abbas, J., Lei, S. & Haider, M., 2017. Transactional leadership and organizational creativity: examining the mediating role of knowledge sharing behavior. Cogent Business and Management, 4(1), pp. 1-9.

Javidan, M., Teagarden, M. & Bowen, D., 2010. Managing yourself: making it overseas. Harvard Business Review, Issue 4, pp. 109-113.

Karaca, M. & Demirtas, O., 2020. A handbook of leadership styles. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lokendra, P. S., 2020. A thought on entrepreneurship and leadership. BFC Publications.

Malhotra, A. & Axelsen, M., 2018. Transformational leadership and not for profits and social enterprises. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Meyer, R. & Meijers, R., 2017. Leadership agility: developing your repertoire of leadership styles. New York: Routledge.

Moone, C. E., 2017. Before and after the project starts: enabling organizational goals while preventing disaster. New York: Page Publishing.

Naktiyok, A. & Emirhan, K., 2018. Exploring the effect of leader member exchange (LMX) level on employees’ psychological contract perceptions. International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 7(2), pp. 120-128.

Northouse, P., 2019. Leadership: theory and practice. 8th ed. Sage.

Poser, N., 2016. Distance leadership in international corporations: why organizations struggle when distances grow. Berlin: Springer.

Ryan, G., Emmerling, R. & Spencer, L., 2009. Distinguishing high-performing European executives: the role of emotional, social and cognitive competencies. Journal of Management Development, 28(9), pp. 859-875.

Schyns, B. & Schilling, J., 2013. How bad are the effects of bad leaders. The Leadership Quaterly, 24(1), pp. 138-158.

Seltzer, J. & Bass, B. M., 1990. Transformational leadership: beyond initiation and consideration. Journal of Management, 16(4), pp. 693-703.

Unterrainer, C., Jeppesen, H. & Jonsson, T., 2017. Distributed leadership agency and its relationship to individual autonomy occupational self-efficacy. Humanistic Management Journal, 2(1), pp. 57-81.

Van Vugt, M., Jepson, S. F., Hart, C. M. & De Cremer, D., 2004. Autocratic leadership in social dilemmas: a threat to group stability. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(1), pp. 1-13.

Vigoda-Gadot, E. & Drory, A., 2016. Handbook of organizational politics: looking back and to the future. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Warren, B. & Nanus, B., 2004. Leaders: strategies for taking charge. s.l.:Business Press.

Western, S., 2019. Leadership: a critical text. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

Yammarino, F., 2013. Leadership: past, present and future. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 20(2), pp. 149-155.

Yukl, G., 2013. Leadership In organizations. 8th ed. Pearson Education.

Zhang, F., Liao, J. & Yuan, J., 2016. Ethical leadership and whistleblowing: collective moral potency and personal identification as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality International Journal, 44(7), pp. 1223-1231.

Appendix: Model of Leadership Ethics