Executive Summary

Low-cost carriers/airlines (LCCs) traces its roots back during the post-deregulation era. The airlines use a different business model: point-to-point route structure. In the recent past, LCCs market has continuously been expanding to include a few international slots. Currently, it is regarded as one of the most profitable airlines due to its ability to offer short haul flights. While there are many LCCs both in the United States and around the globe, Southwest Airlines remain to be the largest carriers. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to explore the concept of service quality and customer satisfaction in relation to LCCs doing short haul flights. The main objective was to identify and evaluate the service dimensions that influence customer satisfaction in order to highlight the key areas that require improvements.

Assessment

Customer’s airline experience occurs in two phases: pre-flight and in-flight. Each phase contains several customer-oriented activities that contribute to total customer experience. The pre-flight activities include booking and security while the in-flight process incorporates interior appearance such as comfort seats. It is important to note that the in-flight phase is the most essential customer-oriented service quality perspective compared to pre-flight activities. Some of the major theoretical concepts in the field of quality management and customer experience that are central to this topic include Juran theory, SERVQUAL model and total quality control by Armand Feigenbaum. SERVQUAL model proposed five quality model dimensions that are critical to the airlines. They include: reliability, tangibles, assurance, responsiveness and empathy.

Reflection

In this section, the focus was on how the industry could improve quality management and customer experience. Some of the opportunities for improvement identified include focusing on the tangibles and assurance dimensions. For instance, with assurance, passengers feel satisfied and safe during short haul flights. Most importantly, the discussion proposed the creation of working environment that motivates flight crew members to give quality responses to customer needs.

Introduction

Global airline industry is one of the most diverse marketplaces which comprise of different market segments, among them full-service carriers (FSCs) and low-cost carriers/ airlines (LCCs). However, the discussion in this paper will revolve around the LCCs that emerged during the post-deregulation era. This new breed of airlines adopted a different business model; point-to-point route structure. Initially, the airlines were doing short haul flights in intrastate routes within the United States. As Belobaba et al. (2015) observed, the LCC market has continuously been expanding to include some international slots. Today, they are considered one of the most profitable airlines with large shares of the market. Their growth is as a result of technological advancements that have facilitated online ticketing and communications.

Southwest Airlines is considered one of the largest low-cost carriers. The firm, currently based in Texas, started its operations in 1969 (Asahi, & Murakami, 2017). It was not until the passage of the deregulation act of 1978 did the airlines expand its services to other states. The main advantages of the Southwest Airlines include reduction of flight delays and low costs due to small fees charged at the smaller airport. They also managed to standardize all of their equipment that saw them operate only one aircraft, Boeing 737. This business model of following point-to-point routing and operating from small airports revolutionized the LCCs.

Therefore, this paper seeks to explore the concept of service quality and customer satisfaction with reference to low-cost airlines doing short-haul flights. The two major phases of airline travel that will be discussed are pre-flight and in-flight activities. These phases contain different customer-focused services and activities that contribute to the total customer experience. Overall, the objective of this paper is to identify and evaluate the service dimensions from a theoretical point of view that influence customer satisfaction, in order to identify areas for improvement.

Assessment

From the customer’s point of view, airline experience occurs through two major phases: the pre-flight and the in-flight. At each phase, the passenger has different needs and requirements which must be met with minimum challenges. However, the in-flight process remains to be the most important customer-focused service perspective compared to pre-flight activities (Etemad-Sajadi et al., 2016). It is important to note that the customer experience starts and ends at the airport. The modern LCC environmental conditions of the pre-flight phase can be divided into three sections: ticketing, security and retailing. These sections come with distinct requirements for the passenger and the management. In most cases, ticketing is managed exclusively by the airline while security is controlled by the national governance. Retailing, on the other hand, is run by third party retailers. Puccinelli et al. (2009) advised retailers to focus more on understanding customer behavior. Therefore, it is imperative to evaluate each section in the pre-flight independently.

LCC has, in the recent past, shifted its focus to offering online e-ticketing and boarding passes. Most of them, including the Southwest Airlines and Ryanair which offers short haul flights, understand that long ticket lines affect efficiency and profitability margins. This explains why many LCCs “charge their customers for printing a boarding pass at the counter” (Malighetti et al., 2009, p. 95). In essence, e-ticketing and online boarding have helped ensure passengers’ airport experience is less stressful besides speeding up the transition to security section. The findings from Sindhav et al. (2006) showed that there is a direct link between increased security measures and passengers satisfaction with air travel experience. However, additional research is needed to determine the impact of airport screening on passengers’ airport experience. Correia et al. (2008) explicated that passenger screening procedures remains to be a major method of evaluating the quality of experience. In other words, security process impact how the passenger behaves as they move to the in-flight phase.

Following the experience at the pre-flight, the passenger enters the next phase of the air travel journey, the in-flight phase. At this stage, the customer experience is “generated through a longer process of company—customer interaction across multiple channels, generated through both functional and emotional clues” (Klaus et al., 2013, p. 315). The air experience at in-flight has changed significantly following the adoption of market liberalization. In early years, the air travel was only limited to a small number of demanding customers. The travelers enjoyed large seats coupled with in-flight meals and gifts such as playing cards. However, the entry of LCCs saw the airlines start offering a variety of ancillary products which range from in-flight entertainment, meals, drinks and lottery cards. By transforming the services into ancillary revenue streams, the LCCs have ensured customers are able to manage the cost associated with air travel by selecting the services they wish to purchase (Meyer, & Schwager, 2007). In fact, some LCCs use their cabins to sell their products like the case of Ryanair.

Almost all LCCs, especially those doing short haul flights, support the idea of selling passenger consumer goods while in-flight. This leads to the creation of a happy environment inside the aircraft. The servicescape and retailing environment of these airlines are directly linked (Fodness and Murray, 2007). These two elements are a major source of revenue stream—once on-board the customer cannot leave to buy food elsewhere. If they become hungry, their only option is to buy food from the airline because they are traveling for short distances. Therefore, these two elements must complement each other for optimum customer experience. In addition to this, there must be a direct relationship between service quality and in-flight sales.

Service Dimensions from a Theoretical Point of View

The concept of quality has been a subject of much discussion in the recent past with a focus now shifting exclusively on perceived quality—“the consumer’s judgment about an entity’s overall excellence or superiority (Parasurana et al., 1988, p. 123). The SERVQUAL model, an instrument designed to capture perceptions of a service, was later developed. The model also aimed at reducing the interaction between consumer and provider based on five service gaps. These gaps include: failure to understand customer expectations, poor service standards, the service/performance gap, service delivery and communications and customer’s expectations vs. perceptions of service. However, much focus was on the Gap 5 which prompted the development of SERVQUAL (Chou et al., 2011). It strived to close the gaps between perceptions and expectations along five dimensions.

First, the Reliability dimension which refers to the ability to perform a given service accurately within the specified timeframe. From an in-flight customer perspective, reliability refers to timely departure, accurate service delivery, doing everything right at first attempt and consistent inspections. According to Chen and Chang (2005), on-time departure, inspections and punctual announcements are more important compared to food and beverages. Secondly, the assurance dimension concerned with the ability of the employees to convey trust and confidence. This dimension is linked to features such as trust among flight crew, knowledge, ability to answer questions accurately, and the level of courteousness among flight crew members (Ghorabaee et al., 2017). The most important feature in this dimension is courteousness because it can damage the trust among customers if not performed well.

The third quality dimension is Tangibles which looks at the appearance of physical facilities, equipment and personnel. In the in-flight phase, customers’ experience is determined by variables such as seat comfort and appearance of flight crew members, entertainment facilities and aircraft interior. Fourthly, empathy dimension is concerned mainly with the following elements: individualized service/personal attention and understanding the needs of the airline passenger including trust needs. However, airline companies find it difficult when it comes to managing empathy due to the heterogeneity among members. The last dimension for consideration is responsiveness concerned mainly with factors associated with efficiency such as comfort seating and safety instructions. Similarly, the ability to handle complaints, requests and inquiries are also critical to this dimension.

Garvin further proposed eight important dimensions of quality that can act as a framework for strategic analysis. These dimensions include reliability, serviceability, perceived quality, performance, durability, aesthetics, features and conformance (Garvin, 1988). Some of these dimensions are naturally reinforcing whiles others have some limitations—changes in one may be done at the expense of others. However, by understanding the trade-offs fronted by customers from these dimensions, airline companies will be able to build a competitive advantage.

Juran and Armand Feigenbaum

Joseph Juran theory is cited as one of the main contributors of “Quality Trilogy” which consists of elements such as quality planning, improvement and control. For instance, airline companies must put into consideration all quality enhancement actions in order to succeed in their quality projects (Androniceanu, 2017). Juran proposed ten steps that served as the guiding principles of quality improvements (Klefsjo et al., 2006). These steps are: clear understanding of opportunities and reasons for enhancement, setting of measurable objectives for improvement, a well-function organization to accomplish the objectives, mandatory training must be given, initialization of projects, observing the progress, monitoring and appreciation of the performance, reporting on outcomes and tracing of changes.

Armand Feigenbaum build on the views advanced by Juran and later proposed total quality control (TQC) which is a continual process of streamlining supply chain management. In airline companies, TQC encourages different teams from marketing, engineering and purchasing to pursue quality as a single entity (Feigenbaum, 1991). It is imperative for these teams to ensure they share responsibilities for all the phases of design and would only disband when the customers arrive at their designation fully satisfied.

The current customer strategy

The LCC provides its customers with unique experience compared to traditional airlines. One of the customer strategies advanced by the airlines is the unbundling of inclusive service. The purchase of LCC ticket allows the passenger to board a specific aircraft at a scheduled time. The passenger has the option of purchasing additional amenities such as in-flight food and entertainment. Here, the aim is to ensure the customer is able to tie the airline experience to their needs and budget. More specifically, in-flight retailing allows the airline to function both as a service provider and retailer (Puccinelli et al., 2009). The most likely quality problem that might arise at this point revolves around the effect of Service Quality on customer’s purchases intentions. The airline with superior service quality may lead to a high competitive advantage. Therefore, the method with which the customers evaluate service in the low-cost airline industry is considered extremely important.

While this strategy seems viable, there are a few loopholes that should not be ignored. For instance, the law of Diminishing Return argues that a point exists at which continued reduction of costs becomes unprofitable (Mahmoudi, & Feylizadeh, 2018). Since fixed costs are common in different airlines operating in the same market, it is reasonable for them to adopt similar break-even points. This will ensure the minimum price per ticket is the same. The same is necessary because excess-cost cutting affects service quality thus forcing the customers to seek flight services elsewhere. It therefore follows that LCCs cannot compete favorably on prices alone. This explains why in future, the airlines should adopt different competitive strategies that would ensure they provide high quality services even if they operate for short routes.

In line with the above, LCCs also have a different customer strategy than traditional airlines; it has a universal focus on reducing ticket prices. To achieve low ticket prices, many airlines are embracing the idea of reducing fixed costs. This, in return, results in LCCs being one of the most profitable airlines in the U.S and around the world. According to Belobaba et al. (2010), high fixed costs “are a characteristic of the airline industry as a whole” and if well-managed they can guarantee industry survival.

Reflection

As evidenced from the above discussion, many LCCs with the exceptions of Southwest Airlines and Ryanair, do not offer high quality services—they focus more on reducing their operational costs and offering low fares. In essence, most of these airlines are not utilizing service quality for competitive advantage. Airline managers should determine whether perceived quality is one of the critical factors for customer satisfaction and loyalty. They also need to understand the factors that affect passengers’ selection of airlines in order to create a service quality culture (Srinivasan and Kurey, 2014). Srinivasan and Kurey further maintained that when customers are unhappy with the service offered, they tend to use social media to share their displeasure.

As competition in both travel and service sectors continue to increase, the concept of service quality has become largely attractive. By providing high quality services, LCCs can retain more customers while at the same time ensuring its survival and growth in the market place. The good news is that there are several opportunities for improvement based on research. The first opportunity is to focus more on tangibles dimension. Tangibles are critical to LCCs—they influence their perceived service quality. They need to differentiate their tangible facilities including in-flight seats and interiors in order to attain competitive advantage. This will complement their inability to offer comfortable seats because their model centers on simplicity and low price.

Another area of improvement is the assurance dimension which has a positive impact on service quality on LCCs. The focus is to ensure customers are satisfied with the services offered based on their quality of experience (Van Moorsel, 2001). With assurance, passengers feel satisfied and safe during short haul flights. As evidenced in literature, LCC passengers hardly feel safe during flights. Therefore, they need to be assured of their flight safety and crew should be knowledgeable and willing to answer all inquiries raised by the passengers.

Overall, this paper proposes the creation of a working environment that motivates flight crew to give quality responses to the customer needs. This is critical when it comes to pulling service-profit chain of the airlines. Zeithaml et al. (1988) observed in their study the need for companies to invest more in communication and control processes in the delivery of service quality. Naseem et al. (2011, p. 23) further noted that “Satisfied employees generate customer satisfaction by excellence in performance that leads to organizational success thus resulting in improved financial success”. This paper encourages airline companies to focus more understanding what flight crew feel, think and desire as well as determine how they can increase workforce devotion and commitment.

Conclusion

This paper aimed at exploring the concepts of service quality and customer satisfaction with a focus on low cost airlines doing short-haul flights. The discussion also analyzed whether or not the low cost airlines are providing the best experience to their customers and the quality issues involved. As evidenced above, most LCC airlines are not utilizing service quality for competitive advantage. They are more focused on transforming their services into ancillary revenue streams, which ensures their customers are able to manage the cost associated with air travel. In other words, the airlines’ main strategy is to offer flight services at a lower cost. Therefore, there is a need for LCCs to provide high quality services in order to retain more customers while at the same time ensure its survival and growth in the market place. There are several opportunities for improvement such as assurance and tangibles dimensions, which if explored will have a positive impact on quality. For instance, tangibles as a quality dimension looks at the appearance of physical facilities, equipment and personnel.

Annexes

References

Androniceanu, A. (2017). The three-dimensional approach of Total Quality Management, an essential strategic option for business excellence. Amfiteatru Economic, 19(44), 61-78.

Asahi, R., & Murakami, H. (2017). Effects of Southwest Airlines’ entry and airport dominance. Journal of Air Transport Management, 64, 86-90. Web.

Belobaba, P., Odoni, A., & Barnhart, C. (Eds.). (2015). The global airline industry. John Wiley & Sons.

Chen, F. Y., & Chang, Y. H. (2005). Examining airline service quality from a process perspective. Journal of Air Transport Management, 11(2), 79-87. Web.

Chou, C. C., Liu, L. J., Huang, S. F., Yih, J. M., & Han, T. C. (2011). An evaluation of airline service quality using the fuzzy weighted SERVQUAL method. Applied Soft Computing, 11(2), 2117-2128. Web.

Correia, A. R., Wirasinghe, S. C., & de Barros, A. G. (2008). A global index for level of service evaluation at airport passenger terminals. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 44(4), 607-620. Web.

Etemad-Sajadi, R., Way, S. A., & Bohrer, L. (2016). Airline passenger loyalty: The distinct effects of airline passenger perceived pre-flight and in-flight service quality. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 57(2), 219-225. Web.

Feigenbaum, A. V. (1991). Total quality control. New York.

Fodness, D., & Murray, B. (2007). Passengers’ expectations of airport service quality. Journal of Service Marketing

Garvin, D. A. (1988). Managing quality: The strategic and competitive edge. Simon and Schuster.

Ghorabaee, M. K., Amiri, M., Zavadskas, E. K., Turskis, Z., & Antucheviciene, J. (2017). A new hybrid simulation-based assignment approach for evaluating airlines with multiple service quality criteria. Journal of Air Transport Management, 63, 45-60. Web.

Klaus, P. P., & Maklan, S. (2013). Towards a better measure of customer experience. International Journal of Market Research, 55(2), 227-246. Web.

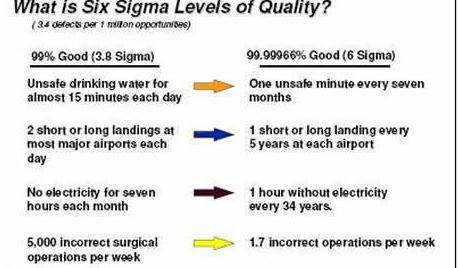

Klefsjo, B., Bergquist, B., & Edgeman, R. L. (2006). Six Sigma and Total Quality Management: different day, same soup?. International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage, 2(2), 162-178. Web.

Mahmoudi, A., & Feylizadeh, M. R. (2018). A grey mathematical model for crashing of projects by considering time, cost, quality, risk and law of diminishing returns. Grey Systems: Theory and Application. Web.

Malighetti, P., Paleari, S., & Redondi, R. (2009). Pricing strategies of low-cost airlines: The Ryanair case study. Journal of Air Transport Management, 15(4), 195-203. Web.

Meyer, C., & Schwager, A. (2007). Understanding customer experience. Harvard business review, 85(2), 116.

Naseem, A., Sheikh, S. E., & Malik, K. P. (2011). Impact of employee satisfaction on success of organization: Relation between customer experience and employee satisfaction. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Sciences and Engineering, 2(5), 41-46.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. 1988, 64(1), 12-40.

Puccinelli, N. M., Goodstein, R. C., Grewal, D., Price, R., Raghubir, P., & Stewart, D. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: understanding the buying process. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 15-30. Web.

Sindhav, B., Holland, J., Rodie, A. R., Adidam, P. T., & Pol, L. G. (2006). The impact of perceived fairness on satisfaction: are airport security measures fair? Does it matter?. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 14(4), 323-335. Web.

Srinivasan, A., & Kurey, B. (2014). Creating a culture of quality. Harvard business review, 92(4), 23-25.

Van Moorsel, A. (2001, September). Metrics for the internet age: Quality of experience and quality of business. In Fifth International Workshop on Performability Modeling of Computer and Communication Systems (Vol. 34, No. 13, pp. 26-31). Arbeitsberichte des Instituts ftir Informatik, University~ it Erlangen-Niirnberg, Germany.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1988). Communication and control processes in the delivery of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 52(2), 35-48. Web.