Reflective portfolios

Reflective portfolios have numerous advantages that enable them to create significant growth in students when applied appropriately. It helps focus one’s thinking, translate theory into practice, and document progress as time passes and their competencies improve (Kadry and El Hami, 2019). Portfolios are also flexible, which is particularly relevant in distance learning, where it is challenging to regulate every student’s schedule (Sivan, 2017). Lastly, reflective portfolios are highly useful aspects of work-integrated education, which is present in many business schools, as they enable the students to reconcile the theory they learn with real-world situations (White, 2019). Overall, they appear to be an excellent tool that is highly suitable for the author’s learning environment, being highly potent and broadly adaptable.

With that said, there are issues with reflective portfolios that complicate their widespread adoption in education. Lam (2018) claims that the adoption of skills that is part of the reflective process is convoluted and can be challenging for students, particularly those with low confidence that are uncomfortable with disclosing their weaknesses. The many stages of self-reflection require active student engagement and consideration, which can be exhausting and lead them to make mistakes. Moreover, if the person is concerned about the disclosure of information about their weaknesses to the instructor, their mistakes will not be apparent, and their effort may be misguided. This possibility is particularly problematic because of the complexity of evaluating reflective portfolios, which compounds the difficulties in determining how appropriate the student’s considerations are.

The difficulty stems from the free-form nature of reflective portfolios and the diversity of situations that can be used for their writing. Neal (2016) discusses how various students’ accounts will typically be broadly inconsistent, both about each other and compared to the other elements of the portfolio. There are several reasons for this tendency, such as student attitude and the limited guidance available. People may underestimate the complexity of writing a reflective account or consider it a less important part of the portfolio, not putting in enough effort as a result. Moreover, the limited number of interactions between students and educators reduces the number of opportunities that exist for these mistakes to be corrected. These considerations make it challenging to implement reflective portfolios broadly due to the student and instructor engagement required.

With that said, provided these elements are present, reflective portfolios can be excellent educational tools. As such, it is essential to guarantee the commitment of both parties to the practice before engaging in it fully. Once it is secured, the reflection will be able to achieve excellent results and improve educational achievements, creating desirable outcomes. The distance learning aspect is particularly relevant because of the current situation, which has forced many schools to switch to a distance learning model. Grant, Murphy, and McKimm (2017) recommend starting with simple tasks, explaining tasks clearly, elaborating on potential concerns and conducting debriefings. All of these practices can contribute to a successful reflective portfolio program that produces the desired results.

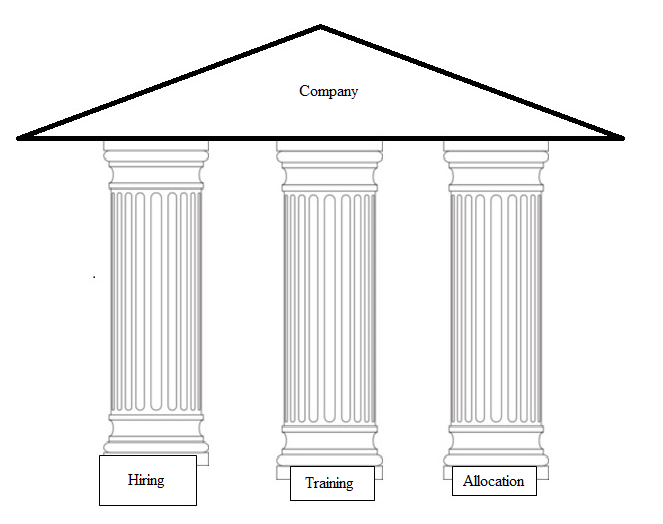

Visual Metaphor

The metaphor represents the role of HR in the organization as well as that which the author intends to fill as a result of their development. They are particularly proficient in hiring as well as talent allocation and development and, as such, they want to capitalize on these skills in their personal growth and professional work. The guidance provided by Williams (n.d.), Cassel, Cunliffe and Grandy (2017), the Information Resources Management Association (2018) and Steen (2018) were helpful for their understanding of the method.

Critical Reflection

Throughout the year, the author has been working on the development of their critical analysis skills, using Nonaka’s framework as well as the justified true belief model. There were no moments that they would describe as significant changes, though their perception has evolved throughout the period. Rather than having any instantaneous revelations that changed their perceptions of critical analysis, the author was able to refine their current understanding of the topic through the models introduced. With that said, peer-assisted learning has been highly beneficial in their education. As is its purpose per Marrone and Draganov (2016), it has helped the author overcome the challenging tasks in the course. As such, they had to devote less effort to these efforts and could focus on self-development.

During the time that they spent working, the author has been exposed to cross-cultural teams a considerable fraction of the time. Compared to intra-cultural situations, the interactions were different, with sometimes increased tension, which is consistent with Steers and Osland (2019). However, the teams were ultimately able to overcome their challenges and find new solutions that were based on the experiences of the different members, which is one of the benefits of diversity (Nguyen-Phuong-Mai, 2019). As such, the author has grown to appreciate cross-cultural teams, though they are also aware that there can be considerable difficulties that are associated with the concept.

Listening to external speakers and MBA talks was particularly interesting for the author because of the formats of their presentations. They discussed unusual practical situations and their solutions, which provided an insight into the thought processes of industry professionals. These experiences helped the author integrate theory into their actual work by analyzing the scenarios and comparing the speaker’s response with that recommended by their learning. With that said, the author was unable to attend the CIPD labor law renewal, employee health and wellbeing, and HR influence workshops because of time constraints. They would have liked to have participated in these events because they could have also provided them with practical experience. Overall, they felt that there was not enough practical learning in their curriculum throughout the year.

Before entering the program, the author had not worked in human resource management, taking on the position of an HRBP assistant in the second semester. They have become familiar with the team, learning how to better interact with them in part through the usage of critical reflection and the portfolio to recognize and address their faults. Of the factors listed in the CIPD HR profession map as depicted by Taylor and Woodhams (2016), they were most interested in resources and talent planning. The idea, formerly reduced in value, has been gaining prominence recently (Taylor, 2018) and attracted the author’s interest, hence its inclusion in the metaphor. Other aspects, such as employee relations and engagement, were more challenging, and the author will try to master them.

Reference List

- Cassel, C., Cunliffe, A. L. and Grandy, G. (eds.) (2017). The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods. London: SAGE Publications.

- Grant, A., Murphy, F. and McKimm, J. (2017) Developing reflective practice: a guide for medical students, doctors and teachers. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Information Resources Management Association (2018) Applications of neuroscience: breakthroughs in research and practice. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Kadry, S. and El Hami, A. (eds.) (2019) E-systems for the 21st century: concept, developments, and applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Lam, R. (2018) Portfolio assessment for the teaching and learning of writing. Cham: Springer.

- Marrone, M. and Draganov, L. (2016) ‘Peer assisted learning: strategies to increase student attendance and student success in accounting’, in Wood, L. N. and Breyer, Y. A. (eds.) Success in higher education: transitions to, within and from university. Cham: Springer, pp. 149-166.

- Neal, M. (2016) ‘The perils of standing alone: reflective writing in relationship to other texts’, in Yancey, K. B. (ed.) A rhetoric of reflection. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, pp. 64-83.

- Nguyen-Phuong-Mai, M. (2019) Cross-cultural management: with insights from brain science. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis.

- Sivan, A. (2017) ‘The use of E-portfolio for outside classroom learning’, in Chaudhury, T. and Cabau, B. (eds.) E-portfolios in higher education: a multidisciplinary approach. Cham: Springer, pp. 117-130.

- Steen, G. J. (ed.) (2018) Visual metaphor: structure and process. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Steers, R. M. and Osland, J. S. (2019) Management across cultures: challenges, strategies, and skills. 4th edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, S. (2018) Resourcing and talent management. London: Kogan Page.

- Taylor, S. and Woodhams, C. (eds.) (2016) Studying human resource management. 2nd edn. London: Kogan Page.

- White, A. (2019) ‘ePortfolios: integrating learning, creating connections and authentic assessments’, in Allan, C. N., Campbell, C. and Crough, J. (eds.) Blended learning designs in STEM higher education: putting learning first. Cham: Springer, pp. 167-188.

- Williams, V. S. (n.d.) Creating effective visual metaphors. Web.