Abstract

- Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic had a tremendous impact on all aspects of companies’ operations worldwide, including corporate culture. Culture needs to go through a planned change to adhere to the new external environment. However, in order to succeed in change management, it is crucial to address possible resistance to change. Examining the variables that influence resistance to cultural change in multinational corporations operating in Qatar’s oil and gas industry is the aim of the current study. The research will be guided by four research questions, which will be discussed in light of Lewin’s force field model, Kotter’s eight-step change theory, and Hofstede’s model of cultural dimensions.

- Literature Review: The preliminary literature review provided significant insights into the topic of interest. In particular, five theoretical frameworks concerning change management were assessed, peculiarities of culture change were discussed, factors that contribute to resistance to change were listed, and practices that help to address resistance to change were provided. Finally, a discussion of the relevance of the concept of “resistance to change” was included.

- Methods: The proposed research is expected to employ a mixed-method approach to answer the research questions. The qualitative part will test eight hypotheses by collecting data from the top and middle managers and analyzing it using multiple regression analysis and descriptive statistics. The quantitative part will assess the degree of resistance in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas industry in Qatar and assess factors that affect resistance to culture change. The qualitative part will collect data from interviews with top managers and designated change managers and analyze it using thematic analysis. The qualitative part of the research is expected to describe the peculiarities of change management in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas industry in Qatar and provide a list of possible strategies to address resistance to change.

Introduction

Background Information

Change Management

The modern reality of business is highly susceptible to change due to the quickly changing internal and external environments (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). Most international companies understand that without continuous change, the companies will become non-competitive quickly. Beer and Nohria (2000) state, “Not since the Industrial Revolution have the stakes of dealing with change been so high. Most traditional organizations have accepted, in theory at least, that they must either change or die” (p. 133). Thus, change management has become one of the central factors of success for companies of all sizes (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). Organizational change management is the key to companies’ growth, as it allows to adopt new technology, methods, and attitudes effectively and use it to improve organizational performance (Stobierski, 2020). Without a functional process of organizational change, companies’ transition can be slow and expensive, which can make them lose the competitive edge (Stobierski, 2020). Therefore, many companies often hire outside firms or individual consults to evaluate the current change management process and help to adopt more efficient change management processes.

Change management has grown into an industry of its own. The change management industries include politicians, business schools, prominent corporate leaders, the media, and the business press in addition to consulting businesses and individual gurus (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). Additionally, change management has received increased attention from scholars. For instance, a recent article by Rosenbaum, More, and Steane (2018) aimed at evaluating various change management frameworks, such as Lewin’s three-step theory. Mobtahej (2020) explored the psychology of change management in the software engineering industry. Kho, Gillespie, and Martin-Khan (2020) discussed change management practices in light of introducing telemedicine in hospitals of different sizes. Thus, change management in different industries is a topic of increased attention from scholars. Of the most complicated change management tasks is to modify the existing organizational culture.

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is usually understood as a collection of values, practices, expectations, and norms within an organization (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). Schein and Schein (2016) describe 12 components that are usually included in the concept of organizational culture:

- Observed behavioral regularities in the interaction of member of one organization. This aspect includes conversation patterns, typical responses to praise or criticism, interaction customs, and traditions.

- Climate. This component is associated with the feelings conveyed through the interaction between members.

- Formal rituals and celebrations. This aspect includes celebrations of key events in an organization. The list of all the events that are celebrated is also crucial for the organizations culture.

- Espoused values. Such values are formally announced or written in the organization’s documents. These values are also usually included in the corporate website and recruiting documents.

- Formal philosophy. Such philosophy is a clearly stated in the regulatory documents and includes key guiding principles of the attitude towards shareholders, customers, and employees.

- Group norms. Unlike espoused values, group norms include implicit standards and values that emerge in the process of the communication between group members.

- Rules of the game. This aspect of organizational culture includes unwritten rules of getting alone in an organization that a newcomer must learn to be accepted by the rest of the team members.

- Identity and image of self. This constituency of organizational culture is associated with the statement of how organization understands its purpose and mission.

- Embedded skills. These are abilities passed on from one member of an organization to another, which are not included in any written documentation.

- Mental models. These models are explained as shared cognitive frameworks that influence perception, thoughts, and language of the group members.

- Shared meanings. Words may have different meanings from one organization to another, and the set of meaning associated with different words is one of the key components of the organization structure.

- Integrating symbols. These symbols are characteristics the organization uses towards itself.

Organizational culture also has four crucial characteristics described by Schein and Schein (2016), including structural stability, depth, breadth, and pattering. Different cultures differ on the bases of these four aspects.

Culture Change

Research about organizational culture change is scarce, as organizational culture is difficult to define, understand, and describe (Muscalu, 2014). In general, culture change can be described as a crucial organizational change that involves changing one or several aspects of organizational culture (Schein and Schein, 2016). The importance of culture change is difficult to overstate, as organizational culture can be a facilitator or a barrier to other organizational changes (Muscalu, 2014). Culture change is a difficult undertaking, as it presupposes a change of deeply rooted aspects of organizational behavior, which may not be evident (Denning, 2011). Culture change is a planned change that is usually sustained using one of the organization’s change frameworks or theories (Willis et al., 2016). Culture change is a significant undertaking that can be implemented only by a skilled leader. The success of the change is highly dependent on the ability of the change agent to use all the available organizational tools (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). According to Denning (2011), the organization tools for changing culture include leadership tools (vision, storytelling, persuasion, communication, role modeling), management tools (negotiating, strategic planning, decision-making, learning, role definition, control systems, incentives, rituals), and power tools (hiring, firing, threats, coercion). While culture change is an understudied topic in general, even less research is available for the oil and gas sectors in Qatar.

Qatar’s Oil and Gas Sector

Qatar has a vastly developed energy sector that has been developing steadily for the past half a century. The sector includes a diversified array of both state-owned and private companies that participate in nearly all major energy-related projects (Oxford Business Group, 2016). The major players in the industry include Doha Petroleum Construction Co Ltd, Dolphin Energy, Petrofac Qatar, Petrotec Group, Qatar Petroleum (QP), Qatargas, and Supreme Supply Service. The state giant and the dominant company in the sector, QP, controls almost all aspects of the gas industry in Qatar, including exploration, production, transportation, storage, marketing, and sales (Oxford Business Group, 2016). The company was established in 1974, and since then, it has been responsible for all oil and gas industries in the country. The major onshore locations include Doha, Dukhan, and Ras Laffan, while offshore locations include Halul Island and the North Field (Energy Year, 2021). The North Filed is known to be the largest non-associated natural gas field (Energy Year, 2021).

At present, Qatar has one of the largest reserves of oil and gas in the world. Its current gas reserves are 24.9 trillion cubic meters, while its annual production is 175.7 billion cubic meters (Energy Year, 2021). The oil reserves of the country are estimated at 25.2 billion barrels, while its annual production is 1.92 million barrels (Energy Year, 2021). The country invested in the liquefaction of natural gas at the beginning of the 21st century, which allowed it to become a world leader in liquid natural gas (LNG) production (Oxford Business Group, 2016). According to Energy Year (2021), “more than 90% of Qatar’s LNG production is committed through supply purchase agreements between 2014 and 2021” (para. 3). Even though the majority of exports have been shipped on the basis of long-term contracts, the percentage of short-term contracts is increasing due to the growth of the LNG market and the tendency to supplier diversification of the main consumers (Energy Year, 2021).

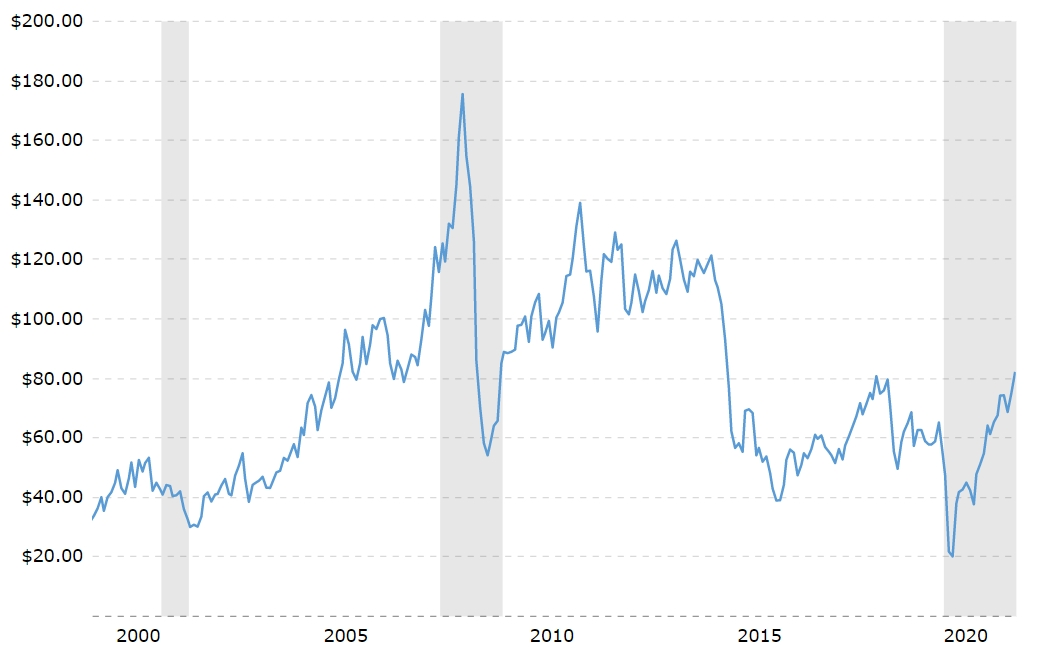

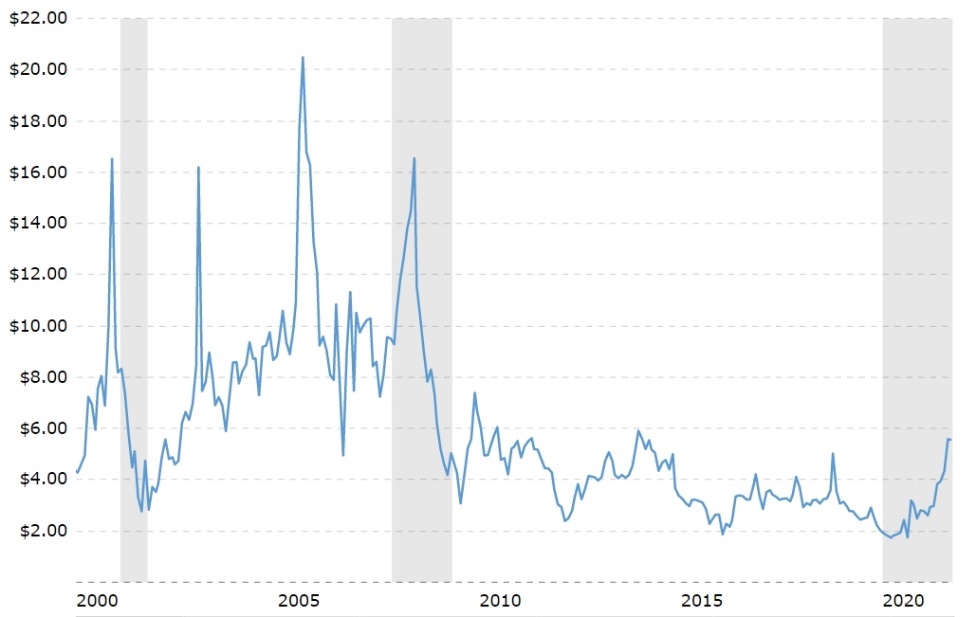

The COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on the world oil and gas market, which affected Qatar’s major players. In 2020, the demand for oil and gas decreased by 25% in comparison with the pre-COVID period (Deloitte, 2021). Even though the industry rebounded at the end of 2020, the overall industry growth was negative at 8% in comparison with 2019 (Deloitte, 2021). In 2021, the oil and gas industry is expected to grow at the level of 4-7% below the pre-VOCID period (Deloitte, 2021). Even though the industry experienced numerous economic recessions, the current situation is unlike any other, as the overall decline in consumption was unprecedented, and its combination with the long-term trend of petroleum and fossil fuel demand may make numerous players in the industry fight for survival (Deloitte, 2021). The tendency in the industry is reflected in the oil and gas price fluctuations provided in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

One of the central attempts to address the growing problem of low demand for gas and oil, QP put increased emphasis on LNG production. Today, Qatari LNG is considered the cheapest in the world, as the break-even price of LNG is only $4 per million British thermal units (mmBtu), while Russia and Mozambique’s break-even price is between $5 and $8 per mmBtu (Jaganathan, 2021). Moreover, QP announced that it will increase the LNG output by 40% between 2021 and 2026, which will allow the company to cover the demand from both South Korea and Japan, the world’s largest LNG consumers (Jaganathan, 2021). Such dedication to LNG is expected to decrease the pressure on Qatar’s oil and gas industry associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theoretical Context

Lewin’s Force Filed Model

Lewin’s force field analysis is a valuable tool that helps to facilitate the decision-making process in all spheres. It was originally created by Kurt Lewin as a part of social psychology in the 1940s (Lewin, 2013). Today, the model is used for managing organizations and making business decisions based on the analysis of drivers and barriers to change. For instance, Makand Chang (2019) examined the driving and restraining forces that affect the adoption of environmental strategies in the hotel industry. One of the conclusions of the study was that using the force field model was associated with significant benefits for analyzing organizational change. Sharma, Singh, and Matai (2018) analyzed the barriers and the driving forces for adopting strategic sourcing risk management in the automotive industry. Utilization of the model led to valuable insights through analysis of literature. Mahmud, Mohd Nasri, and Syed-Abdullah (2019) studied factors affecting the implementation of the whole-university approach towards sustainability using Lewin’s framework. The results revealed that the force field model is also applicable to decision-making in the education sector. Thus, the use of Lewin’s model appears suitable for analyzing the factors that contribute to the resistance to change in the multi-national corporations in the oil and gas industry in Qatar.

The decision-making model promoted by Lewin (2013) can be broken down into five stages described below:

- Describing the proposal to change. This step includes stating the purpose of change and outlining all the steps that will lead to the desired goal. Describing the desired change can be helpful for understanding all the stakeholders and processes involved in the decision-making process, which will help to determine the drivers and barriers change.

- Identifying forces for change. This stage is associated with describing drivers for change that can be both internal and external. The internal factors may be rapidly decreasing team morale, reduced operations efficiency, and declining profit margins. External factors may include disruptive technology, industry uncertainty, and changing demographic trends.

- Identifying forces against change. This phase includes determining internal and external factors that can prevent the success of the change. Internal factors may include fear of uncertainty and dysfunctional organizational structure, while external factors may include government legislations and obligations to customers or creditors.

- Assigning scores. This step includes a thorough assessment of the strength of all the factors to understand how impactful they are for achieving the purpose.

- Analyzing and decision-making. This step is associated with making the final decision whether to implement the promoted strategy. If a high degree of uncertainty is still present, the change agent may consider which forces against change can be reduced and which forces for change can be strengthened. The strategies for manipulation with these forces should be described and implemented, which will allow the re-evaluation of the decision.

Kotter’s Theory of Change

John Kotter is considered a leadership and change management guru. A professor at the Harvard Business School and a world-renowned change expert, he has created an eight-step process for change management (Harvard Business School, no date). He is known to be “the premier voice on how the best organizations achieve successful transformations” (Harvard Business School, no date: para. 1). In 1996, Kotter published a framework of the eight-step model of change, which was recognized by scholars around the globe. These eight steps include the following (Kotter, 2012):

- Creating a sense of urgency. The first step is associated with using appropriate techniques to give all the stakeholders an understanding that a change is urgently needed to avoid disastrous consequences or grab a unique opportunity.

- Forming a powerful guiding coalition. This stage is associated with building a team that can lead the change in the organization.

- Developing a strategy and vision for the change. During the third step, the team clearly describes the future that can be achieved by implementing the desired change.

- Communicating change vision. This stage promotes the developed vision to all the stakeholders, which can lead to increasing the number of people in the coalition.

- Empowering employees of broad-based action. During this phase, the barriers are to be removed, and drivers for change are to be promoted to enable action from all the employees.

- Creating short-term wins. This step is associated with recognizing short-term results to motivate further improvement.

- Consolidating gains and producing more change. The consolidation of all the micro wins is expected to increase the credibility of the change agent and increase the support to the change plan, which will lead to further change.

- Anchoring the culture change in the organization. The final stage includes articulation of all the changes in behavior and connections between them to ensure that the change is sustained in the future.

Kotter’s change framework is an easy-to-implement, step-by-step model that provides clear descriptions of all that is required to guide the process of change successfully. This model emphasizes encouraging the involvement of all members and increasing the level of acceptability of the employees so that the overall process of change management is successful (Kotter, 2012). The described framework is expected to help in the analysis of the results achieved by the present research.

Hofstede’s Model for Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede presented a novel framework for characterizing and comprehending a nation’s culture in 1980 (Dellner, 2014). There are five dimensions in this model that can be used to evaluate national culture. The five national culture dimensions proposed by Hofstede are as follows (Dellner, 2014):

- Power distance. This dimension describes the degree to which the nation’s weaker citizens tolerate the unequal allocation of power. The higher the power distance index, the more tolerant the people are to strict hierarchy and the absence of power.

- Uncertainty avoidance. The degree to which members of a culture are at ease in unclear circumstances is referred to as this dimension. The higher the index, the more people tend to avoid situations associated with high degrees of uncertainty.

- Individualism vs. collectivism. The degree to which members of that culture prefer working alone rather than as a team is referred to as this dimension. The higher the index is, the more people value individual success and expect everyone to be independent.

- Masculinity vs. femininity. This dimension describes how much people value humility, tenderness, and the quality of life (feminine values) versus competition, achievement, and success (masculine values). The higher the index, the more a country supports masculine values.

- Long-term vs. short-term orientation. This dimension describes how people think about the future. Cultures that are long-term oriented are generally characterized by the values of greater adaptability, persistence, and perseverance. On the other hand, national cultures with a short-term orientation invest less in building relationships and more in obtaining immediate results. The higher the index, the more people tend to be long-term oriented.

The utilization of Hofstede’s model is expected to help in explaining how cultural dimensions associated with Qatari people can help to explain the resistance to change.

Problem, Purpose, Research Questions, and Hypotheses

Problem Statement

The COVID-19 pandemic had a tremendous impact on all aspects of companies’ operations worldwide, including corporate culture. The large-scale social and economic shock has already had a huge impact on organizational cultures worldwide (Spicer, 2020). The cooler talks were replaced with chat room conversations, suits were replaced by face masks and gloves, and round table conversations were replaced by Zoom conferences. Cultures of many companies shifted from being creative and explorative to being defensive and preserving (Spicer, 2020). The problem with such culture change is that it may lead to a disaster if the transition is not controlled (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). However, even controlled change may be associated with multiple barriers. In particular, according to Elliot and Smith (2006), organization members may find the transformation of corporate culture deeply troubling, which may lead to resistance to change. For instance, the corporate culture of Nokia failed to acknowledge the shifted cellphone market in 2007 and resisted to change, which led to an unprecedented fall of the company (Vuori and Huy, 2016). Thus, it is crucial to address the problem of resistance to culture change to avoid problems with the competitiveness of the companies.

As it has been mentioned previously, culture change is an under-discussed topic in the current scholarly and professional literature (Denning, 2011). Even less literature is available on resistance to change in Qatar’s oil and gas sector. However, according to Del Val and Fuentes (2003), resistance to change may be one of the key issues that negatively affect the success of functional culture change. As the overview of the oil and gas sector demonstrated, culture change is crucial in Qatari multi-national corporations operating in the oil and gas market, as the recession in the market is expected to lead to a significant change in the trends of the market (Deloitte, 2021). Thus, it is crucial to determine the sources of resistance to culture change and the unique characteristics of resistance to culture change in Qatar’s oil and gas sector.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of the present research is to examine the factors that affect resistance to culture change in multi-national organizations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. It is anticipated that the identification of these characteristics through the use of diverse research approaches and the testing of various hypotheses will assist managers of multinational firms in carrying out planned organizational culture reform. Furthermore, this study intends to investigate the particular traits of resistance to cultural change in Qatar’s oil and gas business and offer suggestions for overcoming such opposition. Given how little is known about culture change in Qatar, the study is also anticipated to fill a major information vacuum. Additionally, the study will add to the body of knowledge regarding cultural shifts during the COVID-19 pandemic and offer insightful information for further research.

Research Questions

The present study will focus on the following research questions:

- RQ1. What are the unique characteristics of organizational cultures in multi-national corporations in Qatar’s oil and gas sector that affect culture change?

Hofstede’s theory of culture dimensions claims that all countries have unique cultural characteristics that affect organizational cultures. Qatar scored high (93 out of 100) in power distance, which demonstrates that Qatari employees accept a highly hierarchical order, where everyone has its place (Hofstede Insights, no date). At the same time, the country scored low (25) in individualism, which is associated with increased emphasis on group values rather than personal success (Hofstede Insights, no date). It is also crucial no note that Qatar’s uncertainty avoidance index is very high (83), which demonstrates that Qatari people prefer low degrees of unpredictability and tend to have rigid codes and models of behavior (Hofstede Insights, no date). However, multi-national corporations include representatives from many cultures, which implies that these companies will have unique organizational cultures.

- RQ2. What is the degree of resistance to cultural change multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar experience?

The degree of change may vary from country to country depending on the history and values of the nation (McCarthy et al., 2008). Thus, it is crucial to understand how much resistance to change do change managers face in the Qatari oil and gas sector.

- RQ3. What are the factors contributing to resistance to culture change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar?

Resistance to change is associated with multiple factors that contribute (Elliott and Smith, 2006). Every country and industry is expected to have a unique combination of such factors, which need to be assessed to address them and decrease their effect on the success of culture change.

- RQ4. How can resistance to culture change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar be reduced?

Since it has been more than a year since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is expected that many change managers have come up with effective strategies that help to address resistance to culture change. Accumulating all the knowledge is crucial so that other managers can use this information in the future.

Hypotheses

The research will utilize a mixed-method approach to answer the research questions provided above. RQ2 and RQ3 will be answered using quantitative methods, which implies that hypotheses will be tested. The hypotheses identified in the present section concern the factors that affect resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. The hypotheses were formulated after reviewing the literature provided in Section 2.4 of the present paper.

- Hypothesis 1. A quickly changing external environment is positively correlated with resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

Del Val and Fuentes (2003) supported the idea that a quickly changing external environment negatively affects the change process. The COVID-19 pandemic is a source of quick change in the outside environment, which may be a source of resistance in the population under analysis.

- Hypothesis 2. The level of participation in the change management process is negatively correlated with resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

This notion is supported by studies in other industries conducted by Gaylor (2001) and Ghanavatinejad et al. (2018), as well as the theoretical framework by Lewin (1947).

- Hypothesis 3. Manager-employee relationships negatively affect resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

The hypothesis was supported by Gaylor (2001), Del Val and Fuentes (2003), and Amarantou et al. (2016) that conducted research in different industries.

- Hypothesis 4. Communication practices have a negative impact on resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

Gaylor (2001) stated that both quality of information and free communication practices have a significant impact on resistance to change. Del Val and Fuentes (2003) also supported this idea.

- Hypothesis 5. Perceived benefits from change have a negative impact on resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

Amarantou et al. (2016) stated that both personal benefits, such as salary and career, and perceived benefits for the organization are closely correlated with the success of the change process.

- Hypothesis 6. Differences in national cultures have a significant positive correlation with the resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

Amarantou et al. (2016) concluded that personality traits have a significant impact on resistance to change. Additionally, Del Val and Fuentes (2003) concluded that inconsistency in values among individual employees might lead to a significant increase in the resistance to change. Since both personality traits and personal values are the categories of national culture to some extent, it is reasonable to suppose that the fact that companies under analysis have employees from various cultures can affect resistance to change. This assumption is also coherent with Hofstede’s theory of cultural dimensions.

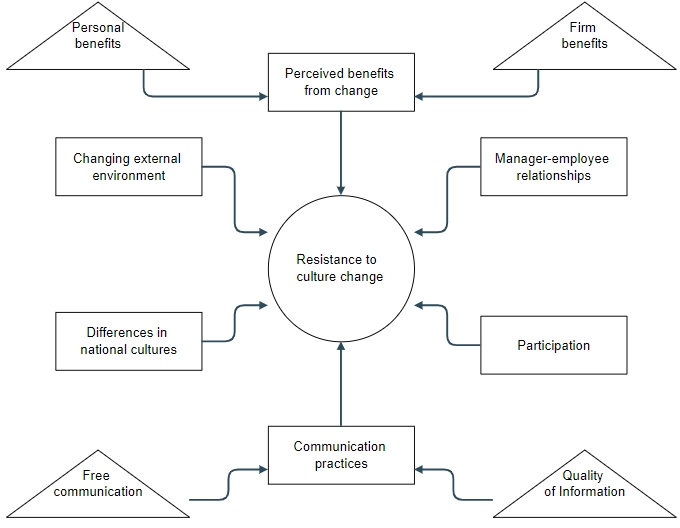

In summary, it hypothesized that resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar is affected by six factors. These factors include perceived benefits from the change, quickly changing external environment, manager-employee relationships, differences in national cultures, participation, and communication practices. The perceived benefits from change consist of two parts, including personal benefits and firm benefits. The concept map for the quantitative part of the present research is provided in Figure 3 below.

Implications of Research

The primary focus of the present research is identifying the factors that influence people to resist culture changes in the organizations and how they can be managed and minimized to proceed with the change successfully. It provides a practical solution to the issues related to culture change management faced by organizations the oil and gas sector in Qatar. First, the present research is expected to summarize all the current knowledge about resistance to culture change, which can be helpful for future research. Second, the study will provide a list of factors that affect resistance to culture change in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. Third, the paper will describe strategies for addressing resistance in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. Thus, the research is expected to provide a list of recommendations that can guide culture change in organizations. This research can also be replicated to improve the generalizability and reliability of findings by exploring other industries and countries.

Acknowledgement of Limitations

It is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of the present research to understand the area of applicability of findings. First, the study is limited by the scope. The purpose of the present research is to explore resistance to culture change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas industry in Qatar. The results will be applicable only to the population under analysis, and applying the results to another country, industry, or type of organization is associated with significant limitations to reliability. In other words, the results of this study can be used to manage change in other organizations with caution.

Second, the research results will be limited by the provided data. Field research results are limited by the credibility, accessibility, and volume of the provided information. During the field research, such problems as wrong, incomplete, or outdated information can be faced along with corporations’ confidentiality rules and their reluctance to provide access to the data. While the researcher will use all the means to increase the validity and reliability of research, data collection bias is expected to be an issue.

Third, the research results are applicable only to the period of the pandemic, as all the data will be gathered during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The current period is associated with a significant degree of uncertainty due to the unpredictable development of the situation with the pandemic. Thus, participants may react differently to culture change during the period under analysis in comparison with their possible reactions during other periods. Thus, the research results may be applicable only to the period of the pandemic. Applying the results of the present research to any other period may be associated with significant bias, which implies that they should be used with caution in such a case.

Preliminary Literature Review

Overview

The purpose of the present section is to provide a brief literature review concerning resistance to culture change and associate topics. First, the review will focus on change management models, including Lewin’s three-step model, Kotter’s eight-step framework, nudge theory, ADKAR framework, and McKinsey 7-S model. Second, the literature review will focus on the peculiarities of change management when the process concerns culture change. Third, the section provides a short overview of possible factors that may affect resistance to change. Fourth, the section focuses on the idea that resistance to change may be an inadequate concept. Finally, a resume of all the findings is provided at the end of this section. A review of factors that affect culture change is not provided as the literature on the subject is scarce.

Change Management Models

Change management is a topic of increased attention from scholars and managers, as constant change is crucial for modern companies to stay competitive in the quickly changing external environment (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). “The process of continuously renewing an organization’s direction, structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers” is how Moran and Brightman (2001) define change management (p. 111). All the companies experience constant change regardless of whether change management practices are employed or not (Burnes, 2004a). To guarantee that change has the intended effects, change management is essential (Burnes, 2004b). Therefore, change management is very closely correlated with strategic management, as change needs to be pointed at improving to reach strategic goals (By, 2004). There are numerous change theories designed to guide change managers in their endeavors (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). However, many of the theories contradict each other, which may cause confusion (By, 2004).

One of the most frequently used change management theories is Kurt Lewin’s three-step approach (Shirey, 2013). The three stages of change are unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. During the first step, change managers need to analyze how things currently work to identify weaknesses and disseminate knowledge about these weaknesses to arouse dissatisfaction among stakeholders about current practices. During the first stage, change is also planned and prepared. The second step is the implementation of the plans created during the first step. The final stage is associated with sustaining the change by transforming the policies and processes to ensure the long-lasting effect of change. There are several drawbacks to the theory mentioned by Burnes (2004b), including the assumption of the fact that a company operates in a stable state, applicability only to small-scale changes, and ignoring organizational powers and politics. However, even though Lewin’s three-step approach is more than 50 years old, it is still applicable in the current circumstances with acknowledgment of limitations (Burnes, 2004b).

Kotter’s eight-step theory may be seen as an extension of Lewin’s theory. Kotter’s (2012) steps include creating a sense of urgency, forming a powerful guiding coalition, developing a strategy and vision for the change, communicating change vision, empowering employees of broad-based action, creating short-term wins, consolidating gains and producing more change, and anchoring the culture change in the organization. The primary benefit of Kotter’s approach is its attention to detail in comparison with Lewin’s change model (Banerjee, Tuffnell, and Alkhadragy, 2019). However, there are also significant drawbacks, including failure to prepare the recipients of change, applicability only to command and control leadership style, lack of measures of success of change, and failure to address resistance to change (Banerjee, Tuffnell, and Alkhadragy, 2019).

While Kotter’s and Lewin’s approaches suggest changing directly by clearly defining goals and implementing relevant policies, the nudge theory suggests a more subtle approach (Kosters and Van der Heijden, 2015). The theory is based on the premise that “nudging” is more effective than forcing change (Hansen and Jespersen, 2013). In the case of nudging, employees are assumed to feel that the idea to change is coming from themselves, which makes the change easier to sustain, as employees themselves become drivers of change (Kosters and Van der Heijden, 2015). There are several steps that need to be accomplished before a change can be implemented, including defining change, considering employees’ viewpoints, gathering evidence for the best option, presenting change as a choice, gathering feedback, limiting options, and using short-term wins to sustain change (Hansen and Jespersen, 2013). While the approach is frequently cited in research, it has not been confirmed by enough evidence, and further research is required to ensure its effectiveness.

ADKAR change management model is another popular approach to change management. The model was introduced by Jeffrey M. Hiatt (2006) and included five drivers of success in change management. ADKAR is an acronym for awareness of the need for change, desire to support change, knowledge about how to change, ability to implement the change, and reinforcement to sustain the change (Hiatt, 2006). Hiatt (2006) claims that these are the basic five steps that cannot be reordered or changed without having a considerable effect on the effectiveness of the change process and resistance to change. The major drawback of the model is its lack of acknowledgment of the complexity of change, which implies that it can be used only for small-scale organizational changes or personal changes (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015).

Another useful framework utilized for change management is the McKinsey 7-S model. The was described by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman in 1982 in their book In the Search for Excellence (Salvarli and Kayiskan, 2018). The model suggests that the company should look at seven factors that ensure best strategy execution practices. These factors include the following (Kaplan, 2005):

- Strategy. The position and actions taken by the company in response to anticipated change.

- Structure. The method the people and objectives are grouped, and the authority is distributed.

- System. All formal and informal procedures utilized within the organization.

- Staff. The people, their skills, experiences, knowledge, and background.

- Skills. The special competencies of the organization that ensure competitive advantage.

- Style. Leadership style and the decision-making culture in the organization.

- Shared values. Explicit and implicit core values that are shared by all the employees in the organization.

The method is appropriate for analyzing the organizational structure to define flaws that can be addressed using change (Ravanfar, 2015). However, the framework does not provide the exact steps that should be taken to drive change effectively and efficiently.

Organizational Culture Change

Organizational culture is often seen as one of the major sustained competitive advantages in the world of quickly changing outside environments (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015). Thus, companies often have an urge to change organizational culture to fit the current situation; however, managers face significant resistance to culture change, which makes the process difficult to plan and implement (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015). Organizational culture consists of three central components, including beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes accepted by the company in a certain situation for a certain person (Muscalu, 2014). These components should all be functional and adherent to top-quality practices (Schein, 1990). This requires a full understanding of the organizational culture and a clear definition of what is expected from organizational culture change (Schein, 1990). The final destination of change should also be coherent with the company’s long-term strategy (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015). Additionally, the change should be achievable in the period of time given. Alvesson and Sveningsson (2015) stated that organizational culture is a very complicated set of explicit and implicit features that may take a long time to change.

One of the most successful culture changes happened in World Bank in the 1970s (Denning, 2014). World Bank had a very complicated culture due to the presence of numerous stakeholders from different countries. The organization had a very obscure culture that varied among different departments and subgroups, which is somewhat common for international organizations (Denning, 2014). Another crucial challenge was that the organization had no clear vision or mission that is crucial for having a functional culture (Schein, 1990). Robert McNamara was able to implement a culture change in the company without formal restructuring or hiring new people; the change was designed and implemented through careful assessment of the current culture, defining the desired state of culture, and close communication with managers to achieve the defined goal (Denning, 2014).

Communication is the key component of successful culture change in any organization. Alvesson and Sveningsson (2015) stated that successful implementation of culture change requires the participation of the entire company, which is impossible without adequate communication practices. Communication may take different forms starting from traditional meetings, online communication, and story-telling through sharing written information among employees (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015; Denning, 2014; Briody, Pester, and Trotter, 2012). Communication is required for creating a positive attitude to culture change and forming a strong alliance among managers and employees (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015). However, communication alone is not enough for successful culture change.

A successful culture change needs to be guided by a clearly defined framework to ensure success (Gibson and Barsade, 2003). The framework can be taken from either theoretical works or from the best practices described in the literature (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015; Ogbonna, E. and Wilkinson, 2003). However, all change needs to be driven by a shift in strategic values and goals (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015; Denning, 2014; Gibson and Barsade, 2003; Willis et al., 2016). The strategic goals and objectives are often dictated by the internal and external environment that affect organizational values both directly and indirectly (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015). Sources of culture change outlined by Muscalu (2014) include:

- Reduced performance of the company in whole or some of its departments;

- Change in the focus of managers;

- Newly adopted organizational vision or mission;

- Response to a crisis or an incidence;

- Newly adopted roles of managers;

- Acknowledgement of differences between the desired and the actual practices and values within the organization;

- Changes in the recruitment or reward practices;

- Low ability of the company to adapt to the changed outside environment;

- Resistance or hostility to the new practices within the company due to inconsistency with culture;

- Change in the company’s rituals.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created an urge for culture change in all types of organizations around the globe. Rituals and practices have changed automatically due to lock-down, social distancing, and remote work (Spicer, 2020). The culture of many companies has changed from that striving for innovation to that seeking resilience and safety (Spicer, 2020). One of the primary concerns of many organizational cultures became the reduction of risks of infection spread and associated morbidity (Singh et al., 2020). Instead of seeking new employment opportunities and career advancement, many employees started to value stability and the ability to work distantly as the primary reasons for selecting a workplace, which changed corporate culture drastically (Guan, Deng, and Zhou, 2020). Without effective practices of planned change, the culture of the companies may change uncontrollably, which may lead to disastrous consequences, among which inconsistency between the implicit and explicit values is the central problem (Muscalu, 2014). However, many researchers argue if planned culture is achievable.

Some researchers claim that managing culture change is impossible, as any culture is deeply rooted in the long evolutionary and revolutionary process (Gibson and Barsade, 2003). Therefore, while addressing some issues in organizational culture may be effective, the entire process of culture change cannot be controlled due to the increased complexity of the matter (Gibson and Barsade, 2003). The problem with managing culture change is the failure of managers to evaluate the deeply-seated values, beliefs, and assumptions that affect the performance of the companies and their internal practices (Fitzgerald, 1998). Thus, many managers fail to manage culture change effectively despite the urge to manage culture change directly (Fitzgerald, 1998). The possibility to manage culture change has been confirmed by empirical research (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2015; Denning, 2014; Gibson and Barsade, 2003; Willis et al., 2016). However, it is a complicated process that should be addressed with care and patience (Fitzgerald, 1998).

Factors Affecting Resistance to Change

There are numerous factors that may affect resistance to change. These factors were formulated from the analysis of different theories and empirical studies. After conducting a thorough literature review, Gaylor (2001) focused on five basic factors that affect resistance to change. First, the level of participation in change management plays a crucial part in how smoothly change is adopted. According to Lewin (1947), one of the best ways to decrease resistance to change is to increase the level of participation of the employees in the change process. In this case, employees co-create the change and acquire a sense of ownership, which makes them a supporter of change (Gaylor, 2001). Second, communication practices within the firm have a significant impact on resistance to change (McCallum, 1997). The rationale behind the idea is that the more open communication is between the managers and other employees, the more likely the employees will be able to communicate their concern or acceptance to change (Gaylor, 2001). Additionally, if the communication is open in the firms, managers can clearly explain the benefits of change to the employees.

The third factor mentioned by Gaylor (2001) is trust in management. The higher the trust in management, the more likely the employees support the opinion of managers in all matters. Therefore, if the managers support change, the majority of employees are likely to support this change also. The fourth factor described by Gaylor (2001) is the quality of provided information to the employees. Even if the communication between managers and employees is free, it is crucial that the managers provide only relevant information about the change to the extent the employees can understand the purpose of the stages of change (Moore and Wegner, 1996). Finally, Gaylor (2001) states that the education level of leaders is crucial for addressing the resistance to change, as more educated leaders can utilize more adequate measures to address the resistance of employees.

A systematic review conducted by Del Val and Fuentes (2003) identified a larger number of possible sources of resistance to change. The factors were divided into two categories, including factors that affect resistance during the formulation stage and factors that affect resistance during the implementation stage. The first category included managerial myopia, denial of unwanted information, the perpetuation of ideas, implicit assumptions, communication barriers, and organizational silence. Additionally, cost of change, history of change failures, inconsistent interests between employees and managers, fast and complex environmental changes, reactive mindset, and inadequate strategic vision are included in this category. The second category includes differences in the company and change values, resistance from departments that will suffer from change, strong disagreement about the nature of the problem, emotional loyalty, and forgetfulness of the social dimensions of change. Moreover, leadership in action, embedded routines, collective action problems, lack of necessary capabilities to promote change, and cynicism are also the key sources of resistance to change.

Amarantou et al. (2016) conducted an empirical study that assessed six factors that may affect resistance to change in healthcare organizations. The researchers revealed that personality traits, perceptions of the benefits from the business process reengineering, job satisfaction, management-employee relationships, disposition towards change, and anticipated impact of change. The results revealed these factors were correlated with the level of resistance towards change. Similarly, Ghanavatinejad et al. (2018) provided evidence that perceived benefits from change and involvement in change have a significant impact on resistance to change. Additionally, Ghanavatinejad et al. (2018) supported the idea that cognitive rigidity, short-term focus, emotional attachment, and routine-seeking affect resistance to change.

Overcoming Resistance to Change

Resistance to change can be managed by addressing the factors that affect it. Lines et al. (2015) identified that one of the central problems with managing change is inadequate expectations from the change itself and the change management process. Therefore, it was found crucial to understand what is the adequate scope of change, the size and duration of change, organizational expectations of change implementation speed, the establishment of formal change agents, and involvement of the change agent in the implementation process (Lines et al., 2015). Change is an increasingly complicated process that requires the participation of a wide variety of stakeholders (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2015). Therefore, the expectations from change and the timeframe should be realistic to ensure the success of the endeavor (Lines et al., 2015). Additionally, the presence and active participation of the internal change agent can improve the effectiveness of the change process by up to 75% (Lines et al., 2015).

Participation in the change management process is another key to reducing the resistance to change. Lewin (1947) claimed that through participation, the employees receive a sense of ownership and become to see the change management process as their own idea. Alas (2007) concluded that motivation is the key to success in the change management process. Alas (2007) note that one of the best ways to increase motivation is to develop a sense of belonging to the process, which can be achieved through participation. Additionally, participation allows meeting the employee needs during the change process (Alas, 2007). Employees may feel that the change affects their status, which automatically causes resistance (Gaylor, 2001). Participation in the change management process can help to address this feeling, as the employees develop a new status in accordance to their needs during the change process (Gaylor, 2001).

Having adequate change management skills is another crucial factor that can help to address resistance to change. According to Bruckman (2008), managers need to be able to understand the change process entirely and navigate the company and its employees in proactive measures to change according to the trends in the outside environment. Managers need to formulate a clear vision and mission of change to understand the expected result and align interventions with the goals and objectives designed to achieve the desired change (Bruckman, 2008). Managers need to understand that resistance to change is another good nor bad, and it should be addressed through full understanding of the process of change rather than through instincts (Bruckman, 2008). While lack of necessary capabilities may increase resistance to change, having a clear understanding of the change process can reduce the barriers towards the aim of planned change (Del Val and Fuentes, 2003).

Leadership style is another factor that may decrease resistance to change. High empowering leadership style is associated with powering sharing and promotion of participation in the decision-making process (Arnold, al., 2000). As a result, employees experience increased participation in the process of change, which is a crucial success factor of change management (Alas, 2007; Gaylor, 2001; Lewin, 1947). Additionally, empowering leadership improves employee-manager relationships and increases trust in managers (Hon, Bloom, and Crant, 2014). According to Del Val and Fuentes (2003), both leader-employee relationships and trust in leaders have a significant impact on resistance to change, which implies that addressing these factors through empowering leadership style can lead to a significant decrease in resistance to change.

The climate within the organization also can help to address resistance to change among employees and managers. Hon, Bloom, and Crant (2014) stated that supporting atmosphere within an organization helps to address the resistance to change. Provision of the required resources, general friendliness, and help can help to overcome anxiety and nervousness at work (Chiaburu and Harrison, 2008). Since the change process is associated with a significant degree of uncertainty, which is usually associated with anxiety, a supportive environment within organizations can lead to decreased resistance from employees (Hon, Bloom, and Crant, 2014). Del Val and Fuentes (2003) also mentioned that implementation climate has a significant impact on resistance to change, which implies that changing the internal climate by providing more support to employees can decrease the resistance to change.

In their article titled Decoding Resistance to Change, Ford and Ford (2009) suggested several strategies that can help to address the change. These strategies are described below:

- Boosting awareness. One of the primary problems that change managers face is the lack of knowledge among first-line personnel about the coming change and associated benefits. Therefore, increasing awareness about these matters can reduce resistance to change.

- Returning to purpose. The employees need to understand that why a change needs to be implemented to form their opinion about it. The employees are more likely to support change when they see the personal reasons for change as well as the benefits for the organization the change may bring.

- Changing the change. Change managers need to understand that employees often care about the company and what it to change; however, they disagree with the planned change due to the potential flaws they see. Therefore, change mangers need to adapt the change to include all the feedback from stakeholders.

- Building engagement. Considering all the ideas in shaping up the change causes the feeling of engagement in the process. The stakeholders start to see the change as their own idea and begin supporting it.

- Competing with the past. The majority of employees remember the results of the previous attempts to change, which may affect their attitude to the new change. Therefore, managers need to demonstrate how the new change is expected to be different from the past failures to ensure employees’ support.

Challenging “Resistance to Change” as a Concept

While resistance to change is a common concept used by scholars and managers, some scholars challenge that resistance to change exists. The idea that employees are a source of resistance is largely based on Lewin’s force field model (Dent and Goldberg, 1999). The idea of the model is that managers need to identify the sources of resistance to change and address them to ensure smooth transition to the desired state (Lewin, 2013). The model essentially puts managers as the change agents against the employees as the source of resistance, which may lead to undesirable consequences. Kotter (1995) observed more than 100 companies and concluded that when a major change was needed, the employees understood the new vision and objectives and wanted change to happen. However, there were some obstacles to change that needed to be overcome to move to the desired state of the organization (Kotter, 1995). Therefore, it can be concluded that employees do not resist the change; instead, they protect their status, comfort, and salaries, which may be affected by change (Dent and Goldberg, 1999). Viewing the employees as an opposing force of change may lead to problems with participation in change management, which is a crucial success factor in change management (Gaylor, 2001; Del Val and Fuentes, 2003). Thus, it may be beneficial abandoning the idea of resistance to change, which may lead to emergence of new approaches to change management.

Summary

The present section revealed that even though change management is a topic of increased interest among scholars and leaders, resistance to culture change remains an underexplored subject. The review of five change models, including Lewin’s three-step model, Kotter’s eight-step framework, nudge theory, ADKAR framework, and McKinsey 7-S model, revealed that all of the steps have their benefits and limitations. Therefore, when managing change, it is crucial to select the most appropriate approach according to the needs of the company and the abilities of the manager. Examination of a literature review concerning culture change revealed that culture is a complicated concept that includes many implicit and explicit components, which makes culture change challenging to manage. However, there is enough evidence to conclude that managing culture change is possible if the leaders have the required skills. The review of factors affecting resistance to change revealed that communication practices, employee participation, manager-employee relationships, changing external environment, and perceived benefits from change are the key factors that lead to resistance to change. The strategies for reducing resistance to change are based on addressing the factors that contribute to it. Finally, the literature review suggests that the idea that there is always resistance to change may limit the understanding of the change management process.

Methodology

Research Design

Design Selection

The nature of the present research is mixed in nature, as it seeks to achieve both depth and breadth of knowledge concerning resistance to culture change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. On the one hand, the research aims at testing the degree to which the factors identified during the literature review affect resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. On the other hand, this research aims at explaining why these factors affect resistance to change and identifying the unique characteristics of change management in Qatar’s multi-national companies in the oil and gas sector due to resistance to change. Therefore, it was identified that a mixed-method approach would be most appropriate for achieving the purpose of the present study.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, and it is used to test hypotheses that emerge from the exploration of a theory or from a literature review (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2019). The quantitative approach requires a clearly formulated hypothesis and rigorous methodology aimed at testing the identified hypotheses (Creswell, 1994). Quantitative methods allow researchers to achieve high breadth, as large numbers of participants can be involved (Hair, 2015). Additionally, quantitative methods are praised for high objectivity and increased accuracy of results, as highly reliable statistical methods are used for data analysis instead of the possibly biased judgment of the researcher (Cooper and Schindler, 2014). Modern technology allows automation of the data collection process through an online survey platform, which makes the data collection process efficient and cost-effective. However, there are several drawbacks of quantitative research that should be considered. In particular, the results are limited by the pre-set answers to survey questions, and less detail can be achieved (Creswell, 2007). Additionally, quantitative research is usually conducted in artificial environment, which may lead to significant bias in the results (Hair, 2015).

Utilization of a quantitative approach is crucial for the present study, as it allows testing the hypotheses identified in Section 1.3.4. However, using only a quantitative approach does not allow identifying unique characteristics of resistance to culture change in Qatar’s multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector. The second part of the research is explorative in nature, and the qualitative approach is inappropriate for exploring a phenomenon to achieve the desired depth of knowledge.

Exploratory studies are conducted to gain a better understanding of a problem that has not been clearly defined (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2019). While the results of such research are important, they are often unpredictable, as the researcher should be willing to change the planned course of study (Creswell, 2012). The purpose of exploratory studies is to identify problems in the general area of interest for future research to focus on specific issues (Cooper and Schindler, 2014). Qualitative research is appropriate for exploratory research because qualitative research seeks to understand phenomena by analyzing behaviors, experiences, and observations made locally (Basias and Pollalis, 2018).

Unlike quantitative research, qualitative studies use open-ended questions and allow participants enough time to think about the questions and answer them in detail. Using qualitative research is associated with significant benefits, including generation of data specific to the industry, decreased number of participants, flexibility, possibility to understand attitudes and behaviors, and provision of much detail (Creswell, 2007). However, qualitative research is also associated with significant disadvantages, such as reliability and validity problems, increased possibility of bias, and low time efficiency (Creswell, 2007).

Utilization of the mixed-method approach for the present study allows benefiting from all the strengths of the approaches and mitigating some of the weaknesses of the approaches. In particular, the lack of depth from the quantitative approach will be complemented by the analysis of qualitative data. Low validity and reliability of the qualitative methods will be addressed by using rigorous methods for quantitative analysis. However, some drawbacks, like low time-efficiency and bias of qualitative data analysis, will remain a significant issue.

Data Sources and Justification of the Choice

All research methods are divided into primary and secondary research methods. Primary research methods include surveys, interviews, focus groups, and observations, while secondary research methods include online research using publicly available data, literature reviews, and case studies (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2019). Since the information on the topic of interest was scarce, secondary research methods were not considered for the present research. Surveys are used to gather information from a defined population group (Creswell, 2007). The survey results are relatively simple to quantify; therefore, surveys are used primarily in quantitative research (Cooper and Schindler, 2014).

Interviews are helpful for receiving meaningful insights from experts in the sphere of interest (Creswell, 2007). Even though interviews may be difficult to analyze, they are a vital source of information for qualitative research (Hair, 2015). Focus groups are another source of data for researchers using the qualitative approach, as participants in the focus groups have a common background and can express their feelings and share their experiences freely (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2019). Observations can be used for both qualitative and quantitative research, as they can provide crucial information from the natural environment without interacting with the participant directly (Creswell, 2012).

In order to achieve the purpose of the present study, surveys, interviews, focus groups, and observations were considered. Since surveys are the primary method of data collection in quantitative research, surveys will be used for identifying the factors that affect resistance to culture change in the multi-national corporation in the oil and gas industry in Qatar. For the qualitative part of the research, semi-structured in-depth interviews were selected as the primary data collection technique. In-depth interviews provide more detailed information in comparison with surveys (Showkat & Parveen, 2017).

While focus groups can be used for a similar purpose, a major drawback of focus groups is the dynamic group effect, which results in the collection of inaccurate information (Creswell, 2007). With one-on-one in-depth interviews, respondents have more time and must come up with words, phrases, and sentences to express their opinion and experience; and their opinions are not affected by other participants (Creswell, 1994). This improves the quality of the information collected. Additionally, confidentiality may be a significant factor in focus groups, as participants may be afraid to reveal sensitive information that may lead to ethical issues (Bougie and Sekaran, 2016).

As for observations, this data collection method is used to learn behavior and values through reading, listening, watching, and touching objects, beings, or phenomena (Creswell, 1994). Observations are crucial when the researcher needs to collect information without disrupting the natural environment (Hair, 2015). Additionally, the method may be crucial for understanding non-verbal behavior, which is a significant part of organizational culture. However, the drawbacks, such as the inability to learn about the past and lack of control, make the data collection method difficult to use for achieving the purpose of the present research. In summary, the primary data collection methods for the present research are surveys and in-depth interviews.

Sampling

Quantitative Portion

The purpose of the quantitative part of the analysis is to identify the factors that affect resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. Since, change is managed on all levels, population under analysis is the top- and middle- managers of multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

Probability sampling method will be used for recruiting participants for the quantitative portion of the present study. Probability sampling methods allow every member of the target population to have an equal chance of being involved in the research (Etikan and Bala, 2017). Simple random sampling, systematic random sampling, stratified sampling, and cluster sampling are the four well recognized kinds of probability sampling techniques (Acharya et al., 2013). To determine the elements influencing resistance to change, probability sampling is essential because selection bias is a major concern in quantitative research. Because it minimizes bias in data collecting, simple random sampling will be utilized. Additionally, because there was little chance of error during the sample procedure, simple random sampling was employed.

The sampling process will be performed by acquiring a list of managers with contacts from the HR department of the corporations and under analysis and associating every possible participant with an identification number. After that, random number generator will be used to select the predefined number of participants. The selected representatives of the population will be emailed invitation to participate in the research. If the required sample size is not achieved after the first recruitment attempt, additional attempts will be conducted using similar procedures.

The required sample size was calculated using the Cochran’s (1977) formula provided below: n= t²*s² /d²

Where:

- t = t-value for the selected alpha level;

- s = estimated standard deviation in the population;

- d = acceptable margin of error for mean being estimated;

It was considered, that the significance (alpha) level for the present research will be 0.05, which is correspondent to the t-value of 1.96. Since a seven-point scale will be used, the standard deviation will be 1.167. It was calculated by dividing the inclusive range of scale (7) by the number of standard deviations that include almost the entire population (6). The acceptable error was identified as 3%, which implies that d is 0.21. It can be calculated by multiplying the points on primary scale (7) by the margin of acceptable error (0.03). After substituting the formula with the calculated values, the preferred sample size was estimated to be 119. The calculations are provided below: n= t²*s² /d²= 1.96² * 1.167² / (7 * 0.03)² = 119

Qualitative Portion

The purpose of the qualitative portion of the study is to identify the unique features of change management and resistance to change in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar. Since change management is a narrow area of management, it was considered that only specialized change managers and top managers can provide with enough detail about the peculiarities of change management in the organizations under analysis. Therefore, the population under analysis is top-managers and designated change managers in multi-national corporations in the oil and gas sector in Qatar.

Non-probability sampling methods will be used for the qualitative part of research, as it is expected to help in achieving adequate representation. Non-probability sampling methods are based a specific selection criteria and different members of the population have different chances of being included in the sample. While non-probability sampling methods may have their advantages, they are associated with significant sampling bias, as it is highly dependent on judgement and skill of the researcher (Elliott and Valliant, 2017). Non-probability sampling methods include convenience, purposive, snowball, and quota sampling. When sample bias is unlikely and identifying the target audience is straightforward, non-probability sampling techniques are employed (Cooper and Schindler, 2014).

A combination of purposive and convenience sampling methods will be used for the present research. According to Showkat and Parveen (2017), purposive sampling is selection of the participants by the researcher, keeping in mind the purpose of the study. In other words, researchers prefer using purposive sampling methods for all the participants to fit an identified profile. Consequently, researchers need to think through the selection criteria in great detail to minimize the sampling bias. While this approach to selection was considered appropriate for the present research, underrepresentation was a significant concern to the researcher. Therefore, convenience sampling was also used to increase the number of participants and ensure reliability of findings.

Convenience sampling refers to selecting participants that are readily available to the researcher due to close geographical proximity or personal acquaintance (Showkat and Parveen, 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic and busy schedules of the representatives of the population under analysis were considered as the major barriers to achieving the desired sample size through purposive sampling only. Thus, convenience sampling was selected to be a supplementary sampling approach.

Qualitative research generally does not intend to generalize to a large population, but a rich and meaningful understanding of an issue. This implies much smaller sample sizes are required in qualitative research than quantitative research. Boddy (2016) concluded that sample sizes are dependent on the research framework utilized for the study. Any sample sizes, even as low as one can be justified, if the research provides meaningful insights (Boddy, 2016). While there are numerous recommendations for the sample size, it is generally considered that a sample of 20 carefully selected participants is appropriate (Sim et al., 2018). Thus, it was decided to conduct 20 interviews for the qualitative part of the research.

Data Collection Procedures

Quantitative Procedures

The data collection process for the qualitative part of the research will be conducted automatically. First, participants will be sent e-mails with an invitation to participate in research. According to Heerman et al. (2017), technology-based recruitment methods are effective for securing the required sample. However, there are two major concerns with the technology-based recruitment process. On the one hand, technology-based recruitment is associated with comparatively low response rates (Moraes et al., 2021). On the other hand, emails may lead to a decreased diversification in the sample in terms of age and race (Heerman et al., 2017). Thus, the emails will be supplemented by an announcement from HR managers in the companies under analysis.

Second, after receiving the initial reply, the participants will be sent a link to the survey on the Survey Monkey web-site. Survey Monkey, along with Qualtrics and Amazon Mechanical Turk, are frequently used online platforms for conducting research that provide the users with the ability to collect an analyze data in an efficient manner (Brandon et al., 2014). The second email will also include a description of the purpose and methods of the research. A detailed description of how the data will be used will also me included in the email. The informed consent will be integrated in the first question of the survey, in which the participants will be asked to confirm that they understand the terms of participation and provide their informed consent to taking part in the research project (see informed consent form in Appendix A). In case the first question is answered negatively or left unanswered, the participant’s answer will not be used in data analysis.

Third, the number of responses will be evaluated to ensure that the needed sample size was achieved. If the number of responses is inadequate, additional recruitment will be conducted using the same procedures. If the desired number of participants is not recruited after three iterations, data analysis will be conducted using the information gathered from the decreased number of participants with an acknowledgement of limitations to results.

The survey will include a total of 14 questions, among which four will be demographic questions, 9 will be content questions, and one of the questions is the informed consent question. The content questions will be based on a seven-point Likert scale. All the questions are provided in Appendix B. The estimated time for the participant to complete the survey is ten minutes.

Qualitative Procedures

For the qualitative part of the process, 20 semi-structured interviews will be conducted. The interview will be conducted in person or using Zoom. Johnson, Scheitle, and Ecklund (2019) state that even though online and phone interviews may be beneficial for some researchers, using in-person interviews is preferred, as in-person interviews provide a higher richness of qualitative data. However, the COVID-19 pandemic, busy schedules, and inconvenience may incline the participants to prefer online interviews to in-person interviews. The number of online interviews will be acknowledged as a limitation to the present study. The estimated time for an interview is one hour. All the interviews will be conducted in English.

A pilot interview will be conducted before conducting the interviews included in the data analysis. According to Majid et al. (2017), interviewing is a complicated process that requires practicing to achieve minimal bias and collect the needed data. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct a pilot interview to understand if the questions ask for the desired data. After conducting the pilot interview, the interviewee will be asked to provide feedback on the questions, interview length, and the behavior of the researcher. After that, a self-assessment of the interview procedure will be conducted, and modifications to the interview process will be made to ensure high reliability and validity of findings. The feedback from the pilot interview will also be considered during the modification process.

During the interviews, eight questions will be asked in a consecutive manner. Even though variations in the ordering of questions are considered acceptable, the order of the questions will be followed to ensure the reliability of findings. The interview questions are based on the insights gained from the preliminary literature review. Open-ended questions will be asked during the interviews. According to Creswell (2012), open-ended questions assume that the participant can give free-form answers, while close-ended questions provide the participant with a set of possible variants for the answers, such as yes-no questions. Open-ended questions allow the participants to think through the answer and provide as much detail as possible (Creswell, 2007). Additionally, open-ended questions do not set a guided path for the answer, which allows the researcher to receive unique replies. Therefore, open-ended questions are crucial for explorative purposes.

All the questions were carefully evaluated before being included in the research. First, the questions were checked for clarity of wording by rereading them several times. Second, the questions were evaluated by experts to decrease the bias of the researcher. The feedback from the experts was used to revise the questions. The final versions of the questions are provided in Appendix C.

The video and audio of the interviews will not be recorded to ensure that the participants feel relaxed during the data collection process. Notes will be made by the researcher during the interviews. After the interview, notes will be converted into a script and sent to the interviewee for verification. Any information that is untrue or unethical will be excluded from the transcripts.

Data Analysis Procedures

Quantitative Data Analysis