Abstract

This paper seeks to discuss the union membership in the United States. This paper discusses membership union in both private and public sectors. The wide difference in the number of union members from the private and public sectors shall be discussed. The tilting weighing balance between the private sectors and public sectors concerning the union membership will be thoroughly discussed. The basic trends in the U.S. union membership shall also be given an in-depth insight. The changing demographic nature; the dominance of different sexes, races, and the type of industry where one works, in addition to the decline of the U.S. union membership, is also going to be elaborated in details. Finally, there will be a conclusion to summarize all that has been discussed in this paper.

Introduction

Workers in the private and public sectors need to thrive in good working. This mission is addressed by the union membership where one joins to have their interest and working condition procedurally protected. This paper, therefore, seeks to discuss the union membership such as; accounting for the disparity in the number of union members working in the both public and private sectors. Additionally, discussing the important trends is in line with the unionization in U.S., population makeup and the of American workers.

The Union Membership in America

A difference exists between the public and private sectors as far as strengthening of workers’ union are concerned. It had been a norm that the private sector would always produce many workers unionizing. The year 2009 seemingly marked a notable change regarding the number of workers joining unions from either the public or private sector (Ahlquist, 2017). The public sectors managed to produce a higher number of union members compared to the private sectors (Stamarski, 2015). The high number of women integrating into wage employment due to promotion of gender equality led to the increase in the number of workers in the public sectors. This has resulted in the need to craft welfares and unions that would protect the interests and working conditions of the workers.

President Kennedy played a key role as far as the union membership of the American workers is concerned. The President, in the year of 1960, issued an executive order that would later see the workers in all levels of the government join unions of their choices through the affirmative action (Sterling, 2021). The federal employees were given the first priority, as per the executive order that President Kennedy issued, to organize themselves into unions. According to the report released by the U.S department of labor analysis of the growth and decline of union membership, the public service sector hosts the large five unions with increase in union membership (Sterling, 2021). Evidently, the union membership in the public sector has a likelihood of continually outpacing that of the private sector.

The U.S. union membership is accompanied by certain important trends that are worth giving some thorough insight. National Labor Relations Act that was passed in 1935 guaranteed workers the right to organize themselves into unions (Sipe, n.d.). The unions would give the workers the opportunity through collective bargaining to push for their favorable working conditions with increased salaries and guaranteed security (Carrell & Heavrin, 2013). These moves by the act resulted in increased union membership in the private sectors in 1930s and 1940s (Macneil et al., 2020). Therefore, the history of unionization has seen almost one century of gradual development in the U.S.

President Kennedy’s executive order influenced the second trend where the public sector union membership significantly climbed in 1960s, having lagged behind in the years before. Union compactness marks the third trend of the U.S. union membership (Dark, 2018). Union density refers to the percentage of workers that belong to a given union. Union density peaked in 1955 in the private sector, where approximately one in three workers belonged to a union. The trend has steadily been declining since 1955, with the public sector having a higher union density up to date (Dark, 2018). Lastly, as far as the trends of the U.S. union membership are concerned, it is prudent to note that the states and local governments passed laws that allowed the workers in the public sectors to unionize, that was in 1960s and 1970s. The trend has, however, remained relatively high up to now.

The states and the local governments passed laws that initiated the workers to unionize. Interestingly enough, even the workers themselves saw the need to unionize. The need by the workers to join unions resulted from the experience at the workplace (Wu et al., 2022). Workers could only be hired in a day, and they would unexpectedly be sent home suppose there was no work. Going to the bathroom or just talking compelled workers to seek permission by raising their hands. The poor wages and unsafe working conditions, in addition to the mentioned instances of intimidation, prompted the workers to join unions that would protect them against unruly employers.

The demographic nature of union membership in the United States has changed over the years. Notably, for the past 30 years, there has been evident and noticeable change in the composition of union membership in the United States. As opposed to the initial composition by the white, black, and Hispanic population, the new percentage dominance of 75 percent, 15 percent, and 11 percent, respectively, marked the new racial changes (Ahlquist, 2017). The male gender had initially dominated the union membership. The male and the female did not have equal opportunities in nearly everything. Succinctly, the female gender was so oppressed and looked at with contempt to an extent that even accessing the basic privileges like joining union membership was not easy.

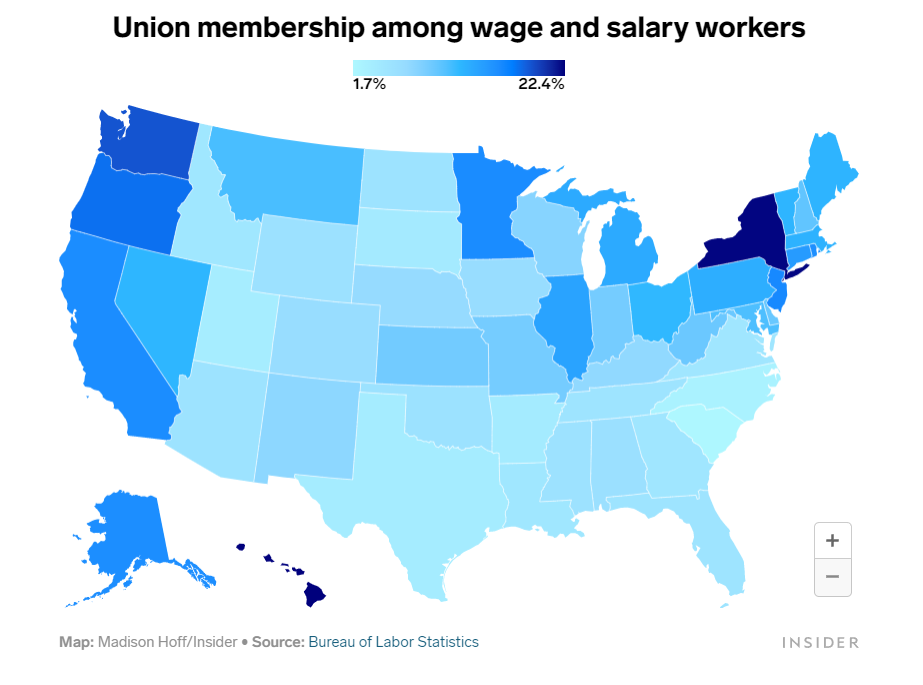

The dominance of the female gender in the U.S. union membership had improved. Initially, it was 34 percent, and it rose to 43 percent (Ahlquist, 2017). The proportion of the female gender in the American workforce has since remained stable. Women, just like men, now have fair opportunities in relation to the accessibility of such services like joining the union membership and having their interests at workplace covered and protected. The union worker image has also changed. Currently, anyone can make a perfect union worker regardless of whether the person is a man or a woman, public or private sector worker, and the type of industry, say construction, manufacturing, or transportation. Overall, the percentage of workers engaged with unions is relatively small, with the range varying from 1.7% in South Carolina to 22.4% in Hawaii, as indicated in Appendix A.

As personal experience suggests, many working people willingly refuse to join unions as they worry about the consequences on behalf of the employer. They say that companies unofficially stand against the unionization, discouraging their employees from defending their rights. The second reported reason for avoiding unionization is the lack of trust in the benefits of membership. In other words, they are unsure of whether these organizations are actually capable of making a difference According to the union workers, the non-union workers have full control in whichever direction they wish to take (McDonald, n.d.). Frustrations from the union leadership also scare most workforces from joining or continuing to be in the union. Labors expect to see a difference between union employers and non-union employers. Unfortunately, there are just similarities, which results in reduced non-union worker interest in joining the union. According to the non-union employee, therefore, unions make no difference.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is important to put in records that there is a wide disparity between the number of workers from the private and public sectors joining membership unions in the U.S. The public sector has since overtaken the private sector in terms of workers unionizing. The demographic pattern of the U.S. union membership has drastically changed with the percentage of women’s dominance in the union membership increasing. The U.S. union membership declines, and there are several reasons attached to that which have been discussed. Additionally, it is evident that union member support most of their goals but are confidence in long term union viability. It is a strong believes by majority that it is unfair for workers to refuse to pay or support the union.

References

Ahlquist, J. S. (2017). Labor unions, political representation, and economic inequality. Annual Review of Political Science, 20(1), 409–432. Web.

Carrell, M. R., & Heavrin, C. (2013). Labor relations and collective bargaining (10th ed.). Pearson.

Dark, T. E. (2018). The unions and the democrats. Cornell University Press. Web.

Kaplan, J., & Hoff, M. (2022). This one map shows what union membership looks like in the US. Insider. Web.

Macneil, J., Bray, M., & Spiess, L. (2019). Unions and collective bargaining in Australia in 2018. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(3), 357-381. Web.

McDonald, C. (1992). U.S. union membership in future decades: A trade unionist’s perspective. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 31(1), 13–30. Web.

Sipe, D. A. (n.d.). A moment of the state: The enactment of the National Labor Relations Act, 1935. University of Pennsylvania. Web.

Stamarski, C. S., & Son Hing, L. S. (2015). Gender inequalities in the workplace: the effects of organizational structures, processes, practices, and decision makers’ sexism. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. Web.

Sterling, R. W. (2021). Through a glass, darkly: Systemic racism, affirmative action, and disproportionate minority contact. Michigan Law Review, 120(3), 451-504. Web.

Wu, S. J., Yuhan Mei, B., & Cervantez, J. (2022). Preferences and perceptions of workplace participation: A Cross-Cultural Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. Web.

Appendix A