Introduction

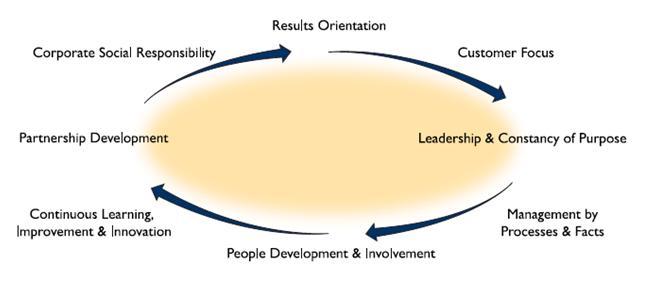

Business excellence refers to exceptional practices adopted by organisations to achieve outstanding results regarding their performance and productivity levels. Businesses are regarded as flourishing if their strategies result in continuous financial profitability compared to others in similar lines of operations. The idea of business excellence is based on eight fundamental principles. They include focusing on customers, results, good leadership founded on specific purposes, management built on facts and processes, the involvement of people and their development, continuous learning, innovation and constant improvement, public responsibility, and partnerships (Doeleman, ten Have, & Ahaus, 2014).

Business excellence emphasises organisations that have remained productive over a long period to the extent of recording continuous success measured based on their extent of meeting customers’ demands. Businesses in this category achieve exemplary rating from economic, social, and technical perspectives for them to be regarded as excellent. Many companies have realised the importance of customer satisfaction in maintaining business excellence. They have introduced measures that cushion customers as a way of securing competitive advantages over their competitors. This literature review examines various business excellence perspectives. It will also compare them with EFQM fundamental concepts of excellence before providing appropriate recommendations that companies can adopt to enhance their current strategies.

Perspectives of Business Excellence

According to Doeleman et al. (2014), the main aim of business excellence is to improve organisations’ structures and systems. Various perspectives focus on enhancing the overall productivity of a business while at the same time boosting stakeholders’ value and confidence. Companies that operate in today’s competitive environments have invested heavily in business excellence approaches as a way of realising sustainable performance levels (Doeleman et al., 2014). By utilising various models, they can focus on the weak areas while capitalising on their strengths. Various perspectives of business excellence have been developed. In particular, according to Bolboli and Reiche (2013), the desire to approach organisational operations in a practical and a professional manner began in the 1960s. The criterion used captured issues such as customer care, quality, decision-making, companies’ ethics, social responsibilities, culture, and actions centred on the environment (Bolboli & Reiche, 2013).

Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman proposed one perspective of business excellence. These two scholars conducted research for two decades on companies with the view of finding out various indicators such as the balance of assets, the accumulated level of assets, the average rise in organisations’ wealth, the standard of institutions’ consumption effectiveness, returns after paying all creditors, and revenue from sales (Bolboli & Reiche, 2013). The results revealed that only a few companies succeeded. As a result, they came up with eight fundamental concepts regarding business excellence.

Firstly, they initiated the idea of predisposition to business, which brings about biasness concerning various organisational approaches, to the extent of interfering with active decision-making. Secondly, they emphasised the need for establishing positive relations between customers and business stakeholders. The third concept entailed autonomy and entrepreneurship, both of which result in sustainable innovations. The fourth element of productivity involved establishing and maintaining a productive pool of employees who would be regarded as idea implementers as a way of encouraging them to produce quality products. The fifth aspect focused on the need for having a management team driven by values and hands-on experience (Doeleman et al., 2014). Peters and Waterman presented an organisation’s management as key in steering business excellence through strategies such as employees’ commitment and engagement in their everyday activities.

Robert Heller established another perspective of business excellence. Robert Heller made a substantial contribution to the early work on business excellence. He based his perspectives of the concept on various key pillars. In his work titled In Search of European Excellence (Ghicajanu, Irimie, Marica, & Munteanu, 2015), this theorist acknowledged European-based companies’ application of ten strategies that were pivotal in ensuring excellence in their respective lines of business. The first perspective of authority transmission involves the delegation of authority to junior management staff members and experienced employees for all people to take part in organisational decision-making processes. In the second perspective, he argued that excellent companies transform the entire enterprise’s culture with the view of aligning it with the desired success (Ghicajanu et al., 2015). This strategy prepares an organisation for the third perspective, namely, the initiation of a radical change. The fourth stage of dividing an organisation to achieve success follows. The fifth strategy involves incorporating new approaches to leadership. Ensuring that a company maintains the first position in its competitive industry of operation forms the sixth perspective. The seventh pillar, namely, acquiring and maintaining regular renewal, implies that an excellent company needs to embrace continuous improvement. Robert Heller’s eighth, ninth, and tenth concepts of business excellence are employee motivation, the formation of work teams, and the achievement of TQM (Ghicajanu et al., 2015).

However, although the above two schools of thought are widely deployed, Jim Collins presents a more recent approach to the concept of business excellence (Ghicajanu et al., 2015). With a group of 20 professionals, he steered research on 28 companies, which he, subsequently, divided into three categories. The first group of companies consisted of 11 organisations. The second category included a similar number of companies. The third group had six companies. Using this sample, Collins and his colleagues arrived at significant conclusions regarding the way some organisations would acquire business excellence while others only manage to perform averagely in their respective environments. These theorists argued that 11 companies recorded business excellence because they possessed level-5 leaders who are well known for confronting the reality and inculcating a culture of discipline.

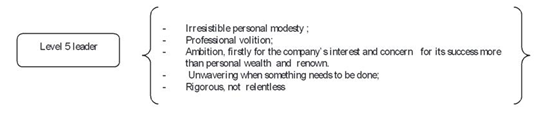

Collins and his team understood leadership as an important aspect of business excellence consisting of five levels. Level 1 leadership is linked to productivity in organisations through good work behaviours, knowledge, and talents (Dahlgaard, Chen, Jang, Banegas, & Dahlgaard-Park, 2013). Level 2 leaders deploy their good personal traits in realising groups’ goals and objectives by encouraging mutual relationships among employees. Hence, in the context of business excellence, such a leader is an outstanding conflict resolver. Level 3 leaders perform remarkably based on their effective resource and people organisation with the outcome of realising established organisational objectives. Level 4 leaders work under rigorous, precise, and clear plans to help in stimulating exceptional performance that complies with the laid-down standards. Figure 1 summarises Collins’ conceptualisation of a level 5 leadership, which is the prerequisite for business excellence.

Compared to Peters and Waterman and Robert Heller’s perspectives, Jim Collins’ presentation of business excellence is convincing. He depicts it as a continuous process that involves the search for remarkable business performance results. Organisations fail to achieve excellence because they focus on performing averagely (Zapata-Cantu, Delgado, & Gonzalez, 2016). Such an argument reflects the actual scenario of modern business environments characterised by changing operations, which compel organisations to realign themselves to secure high performance and, consequently, excellence.

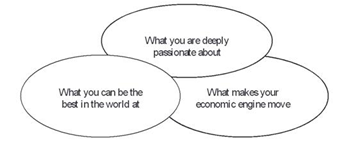

Concepts of business excellence such as motivation and delegation preparation for a radical change, as proposed by Robert Heller’s perspective, are important in the modern competitive business environment. However, according to Asif and Gouthier (2014), knowing what defines organisations, their products and services, and where they object to be in the future, including positions they want to occupy in a world of competition, secures business excellence better in line with Jim Collins’ postulations. As shown in Figure 2, Collins’ perspective addresses this concern through its “hedgehog” concept (Dahlgaard et al., 2013). The perspective also acknowledges the need for being a pioneer in technology to facilitate business excellence, which Peters and Waterman and Robert Heller’s perspectives do not consider. Indeed, technological obsolescence has not only lowered performance but also led to the death of organisations that have been reluctant to embrace Jim Collins’ business excellence perspectives.

A Comparison with the EFQM Fundamental Concepts of Excellence

The European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) is a non-profit organisation that was established almost three decades ago. It began with a membership of 14 businesses that set the pace for business excellence in Europe. The EFQM model was developed as a framework for assessing the extent of sustainability practices with the view of recommending appropriate operations improvement plans. Through this model, all stakeholders are involved in various decision-making processes that emphasise the achievement of the set objectives (Suárez, Calvo-Mora, Roldán, & Periáñez-Cristóbal, 2017). It provides tools that can be utilised to improve organisational profitability and, consequently, performance. According to Edgeman and Eskildsen (2014), the EFQM model is founded on three aspects of excellence, eight central principles, nine decisive factors, and the radar logic. Figure 3 below shows the eight core values.

National bodies develop various business excellence models based on different awards given to exemplarily performing organisations. For instance, the Deming Prize is among the most recognised honours established in 1951 to encourage companies to embrace TQM principles. The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award of 1987 also persuades American-based companies to strive for performance excellence. These medals only serve a secondary importance since the primary goal of such bodies entails ensuring that companies incorporate concepts of business excellence into their management strategies with the anticipation of realising increased economic performance at the national level (Dubey, 2016). Organisations employing business excellence models in their practices aim at identifying potential opportunities for improvement. Their objectives are to come up with frameworks that can steer future developments in their business areas. The EFQM entails one of such models, which provides these opportunities.

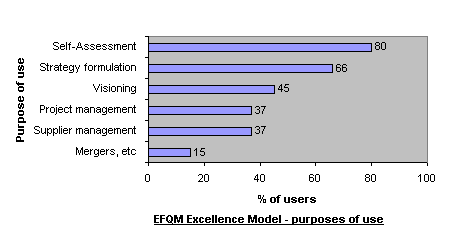

In line with Jim Collins’ views, the EFQM aims at ensuring that organisations adopt outstanding management practices that guarantee long-term business success. The body defines business excellence as entailing various approaches that are aimed at realising outstanding performance in organisational management. According to Escrig and de Menezes (2016), the EFQM’s concepts presented in Figure 3 above suggest that an analysis of the operations performance of any organisation, irrespective of its size, services, or products range it offers for sale, is imperative. It helps companies to remain competitive in the short-term and long-term. Innovation and improvement allow organisations to adopt new practices or operations that effectively lead to increased performance. Sodhi and Tang (2014) present operational performance as the outcome “measured against standards or prescribed indicators of effectiveness, efficiency, and environmental responsibility such as cycle time, productivity, waste reduction, and regulatory performance” (p. 29). These concerns require organisations to engage in healthy processes. The EFQM model captures these aspects, especially upon considering the impact that it has had on organisations that have adopted it as shown in Figure 4 below.

The EFQM model framework is non-perspective. Its architecture is founded on the need for ensuring that organisations become more competitive in their respective market environments. It requires companies to adopt requisite management systems, irrespective of their levels of maturity, organisational structure, operational sector, or size (Vidal & Martínez, 2014). This way, they can acquire both short-term and long-term achievements as captured earlier in Jim Collins’ model of business excellence. In ensuring better operational performance, the model incorporates mechanisms for allowing organisations to measure their status based on the overall success path. The primary objective here is to provide a way of identifying performance gaps and recommending solutions.

The EFQM model has five enablers and four results criteria for determining business excellence. Such enablers consist of processes, commodities and services, policies, institutional headship, people, capital, and success affiliations (Vidal & Martínez, 2014). For outstanding results to be realised, these aspects need to operate in a harmonious manner. Hence, business excellence is a function of different factors that depict a multivariate relationship. In particular, people, the society, business outcome, and clients define the result criterion. The model deploys a RADAR logic (Results, Approaches, Deploy, Assess, Refine), which entails a continuous improvement cycle (Escrig & de Menezes 2016). It requires users of the model to establish outputs that constitute part of its strategy, plan, and then develop various approaches that can help to deliver requisite results in the short-term and long-term. However, an organisation should deploy its adopted approaches systematically to ensure that all strategies are implemented harmoniously. Finally, it should refine and assess its performance approaches by monitoring and analysing results in a manner that enhances continuous learning.

When applied in improving the culture of an organisation, the aspect of business excellence integrated within the model encourages the adoption of best practices in areas that benefit organisations through improved performance and, consequently, profitability. When applied in self-assessment processes, the EFQM model helps in sealing gaps that impede organisational success. Indeed, business excellence tools presented in this framework enables organisations to identify weak and strong performance areas, especially during the benchmarking of best practices for short-term and long-term success (Escrig & de Menezes, 2016). Nevertheless, this model poses some challenges to organisations that use it.

The EFQM model has criteria requiring responses to hundreds of queries. Such questions seek answers on how and/or what an organisation does in its particular areas of focus. They apply to general companies, despite having some inquiries that emphasise specific industries such as education, healthcare, and business (Escrig & de Menezes, 2016). The generality of these questions suggests that managers spend a substantial amount of time in analysing the model to determine aspects that apply to their organisations’ unique circumstances. Companies that seek short-term improvements find it hard to justify the amount of time spent investigating the EFQM model. This concern costs consultants significant resources when finding out how well this model can apply to organisations with a short-term need for excellence.

Similar to other business excellence frameworks, the EFQM model does not offer any solutions that are specific to a given industry in which an organisation operates (Zapata-Cantu et al., 2016). An understanding of the criteria that a company should follow in addressing particular areas of focus helps to enlighten how best to respond to performance problems. Nevertheless, a counterargument emerges that the model fails to offer particular recommendations on the way an organisation can improve its output based on each of its eight important areas. Users are left on their own to determine mechanisms for improving any identified weak areas.

A discussion of purposes, uses, and challenges of the EFQM model raises questions regarding its efficacy. Research on business models, including this one, reveals significant benefits for businesses that deploy them. For example, Escrig and de Menezes (2016) argue that apart from enhancing the financial performance of organisations, the EFQM framework boosts the innovative capacity of an organisation, increases customers and employees’ contentment, and improves operations efficiency. Vidal and Martínez (2014) add that the model contributes to product and service reliability. Nonetheless, although these benefits are debatable, the EFQM tool offers a balanced scorecard, which organisations can utilise to measure or determine the efficacy of their performance management systems. Consequently, they can compare their productivity with standard benchmarks within an industry.

Recommendations

To achieve business excellence, organisations need to direct resources toward key objectives. By focusing on their core mandates, they can find the best approaches to employ to achieve success in terms of performance and productivity. Additionally, they need to focus on their stakeholders who include suppliers, employees, leadership, and customers (Metaxas & Koulouriotis, 2017). By having satisfied stakeholders, companies are set on the path to business excellence. As such, all interested parties should be involved in decision-making processes to ensure that everyone’s part of the bargain is taken into consideration. Importantly, investing in employees is vital because they are well equipped to deal with organisational challenges.

This strategy leads to a wide intellectual base that propels businesses toward success. Another key stakeholder is the customer. Companies that recognise the role of their clients view them as crucial assets (Calvo-Mora, Picón-Berjoyo, Ruiz-Moreno, & Cauzo-Bottala, 2015). In particular, a satisfied customer not only exhibits loyalty to a particular organisation’s products but also is more likely to recommend such commodities to other potential buyers, hence ensuring that the business stays afloat. Therefore, customers’ opinions and complaints should be heard and addressed accordingly. Such grievances should be used to correct any mistakes. In addition, the improvement of products should be done in consultation with customers and other stakeholders to ensure that potential buyers are not lost to competitors. This approach ensures that organisations maintain an edge over their competitors. In turn, a competitive advantage allows businesses to advance discounts to clients as a way of promoting customers’ loyalty.

Good governance structures enhance companies’ levels of achieving desired results. Leadership is pivotal because it acts as the guiding force for organisations’ operations (Carayannis, Grigoroudis, Sindakis, & Walter, 2014). Leaders offer platforms that steer businesses towards their goals. A motivated leadership structure enables all employees to be enthusiastic. In addition, they act as employees’ role models in their organisations. Moreover, the observance of utmost discipline in leadership ranks ensures that the set goals are realised through remaining focused on a particular company’s vision and mission. Organisations should endeavour to always improve all areas of their operations. This goal can be accomplished through research that informs decisions being made. Lastly, organisations that wish to attain business excellence should have well-defined values and cultures that are geared towards the achievement of the desired goals. Consequently, all stakeholders need to be committed to adhering to the laid down principles. The implementation of the above measures will ensure that companies score highly during business excellence assessments, hence securing higher chances of being shortlisted for awards.

Conclusion

Business excellence has become an important concept, especially for companies that wish to succeed in the present-day competitive environment. The aim of business excellence is to improve companies’ structures and systems while at the same time increasing the overall productivity and stakeholders’ value. As a result, they record improved sustainability levels and, consequently, remarkable performances. Unsurprisingly, business excellence awards are among the most sought-after medals. The Deming Prize, the EFQM model, and the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award are some of them. This paper has focused on business excellence in relation to the EFQM framework. Various perspectives of business excellence have been examined suggesting ways of achieving organisational success. In addition, different authors have proposed varying approaches to business excellence. A famous framework by Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman advances eight key concepts. Robert Heller sought to update Peter and Waterman’s approach. Another approach by Jim Collins focused on studying several successful companies. The EFQM model of business excellence has been analysed in details in relation to the role of its various aspects in steering organisational success.

References

Asif, M., & Gouthier, M. (2014). What service excellence can learn from business excellence models. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 25(5/6), 511-531.

Bolboli, S., & Reiche, M. (2013). A model for sustainable business excellence: Implementation and the roadmap. The TQM Journal, 25(4), 331-346.

Calvo-Mora, A., Picón-Berjoyo, A., Ruiz-Moreno, C., & Cauzo-Bottala, L. (2015). Contextual and mediation analysis between TQM critical factors and organisational results in the EFQM excellence model framework. International Journal of Production Research, 53(7), 2186-2201.

Carayannis, E., Grigoroudis, E., Sindakis, S., & Walter, C. (2014). Business model innovation as antecedent of sustainable enterprise excellence and resilience. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5(3), 440-463.

Dahlgaard, J., Chen, C., Jang, J., Banegas, L., & Dahlgaard-Park, S. M. (2013). Business excellence models: Limitations, reflections and further development. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 24(5/6), 519-538.

Doeleman, H. J., ten Have, S., & Ahaus, C. (2014). Empirical evidence on applying the European foundation for quality management excellence model, a literature review. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 25(5-6), 439-460.

Dubey, M. (2016). Developing an agile business excellence model for organisational sustainability. Global Business & Organisational Excellence, 35(2), 60-71.

Edgeman, R., & Eskildsen, J. (2014). Modelling and assessing sustainable enterprise excellence. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(3), 173-187.

Escrig, A., & de Menezes, L. (2016). What is the effect of size on the use of the EFQM excellence mode? International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 36(12), 1800-1820.

Ghicajanu, M., Irimie, S., Marica, L., & Munteanu, R. (2015). Criteria for business excellence in business. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 445-452.

Metaxas, I. N., & Koulouriotis, D. E. (2017). Business excellence measurement: A literature analysis (1990–2016). Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. Web.

Sodhi, M., & Tang, C. (2014). Guiding the next generation of doctoral students in operations management. International Journal of Production Engineering, 150, 28-36.

Suárez, E., Calvo-Mora, A., Roldán, J. L., & Periáñez-Cristóbal, R. (2017). Quantitative research on the EFQM excellence model: A systematic literature review (1991–2015). European Research on Management and Business Economics, 23(3), 147-156.

Vidal, V., & Martínez, M. (2014). The EFQM excellence model in the autonomous region of Galicia (Spain) put to test. International Journal of Management Science & Technology Information, 12, 86-98.

Zapata-Cantu, L, Delgado, J., & Gonzalez, F. (2016). Resource and dynamic capabilities in business excellence models to enhance competitiveness. TQM Journal, 28(6), 847-868.