Recently, increased concerns have been surfacing about human resource management and the preparedness of the educational system to address emerging challenges. According to Dundon and Rafferty (2018), professionals currently focus excessively on the interests of their employer to the detriment of the other stakeholders. Guerci, Radaelli and Shani (2019) highlight a reduction in the relevance of the knowledge that is taught in HRM education to the profession. As a result, researchers such as Macklin and Mathison (2018) propose the introduction of a reflexive ethics-focused approach. Caspersz and Olaru (2017) also suggest service-learning, which they define as “a process of reflective education in which students learn civic or social responsibility through a scholarship of community engagement that embodies the principle of reciprocity,” as a valid approach (p. 686). Many narratives, including those that are described above, prominently feature the notion of reflective learning, which is conducted through reflective portfolios.

Reflective portfolios differ from the traditional model of learning in their increased focus on the student and their experiences. Fullana et al. (2016) claim that students can improve their understanding of the state of their learning and motivations as the result of the practice’s application. Billett, Cain and Le (2018) support this claim by adding that students learn to evaluate their weaknesses through reflective portfolios and develop the skills that they lack at the time. Händel, Wimmer and Ziegler (2020) find a positive association between the usage of portfolios and student exam performance. Sugrue et al. (2018) indicate that trends of increasing reflective portfolio adoption in higher education are emerging as a result. The methodology is particularly useful for HRM professionals because of its applicability to practice.

However, the reflective approach also has some issues that complicate its practical implementation. Griggs et al. (2018) find some evidence of students translating their reflective knowledge into practice, but the process is not straightforward and varies ineffectiveness. Fillery-Travis and Robinson (2018) emphasize the supervisor’s role in guaranteeing the effectiveness of the process, which demands considerable competencies. As Aoun, Vatanasakdakul and Ang (2018) note, without high-quality feedback, the reflective process becomes considerably less effective, removing the method’s primary advantage. The implementation of reflective practice puts a considerable burden on both the students and the educators.

Nevertheless, many educational institutions have adopted reflective practices in their curricula. Armsby, Costley and Cranfield (2018) describe its widespread adoption in doctorate programs for practicing professionals. Guerci et al. (2019) recommend the usage of reflective critique in HRM education to enable students to explore different perspectives and make superior decisions. Kianto, Sáenz and Aramburu (2017) find reflection to be essential to the accumulation of intellectual capital and use reflective models in their modeling of HRM operations. Lastly, Clarke (2018) describes reflective thinking as a critical element that must be present in an employable graduate. Overall, the utility of reflective portfolios is well-established in the literature, and they are adopted throughout various higher education facilities.

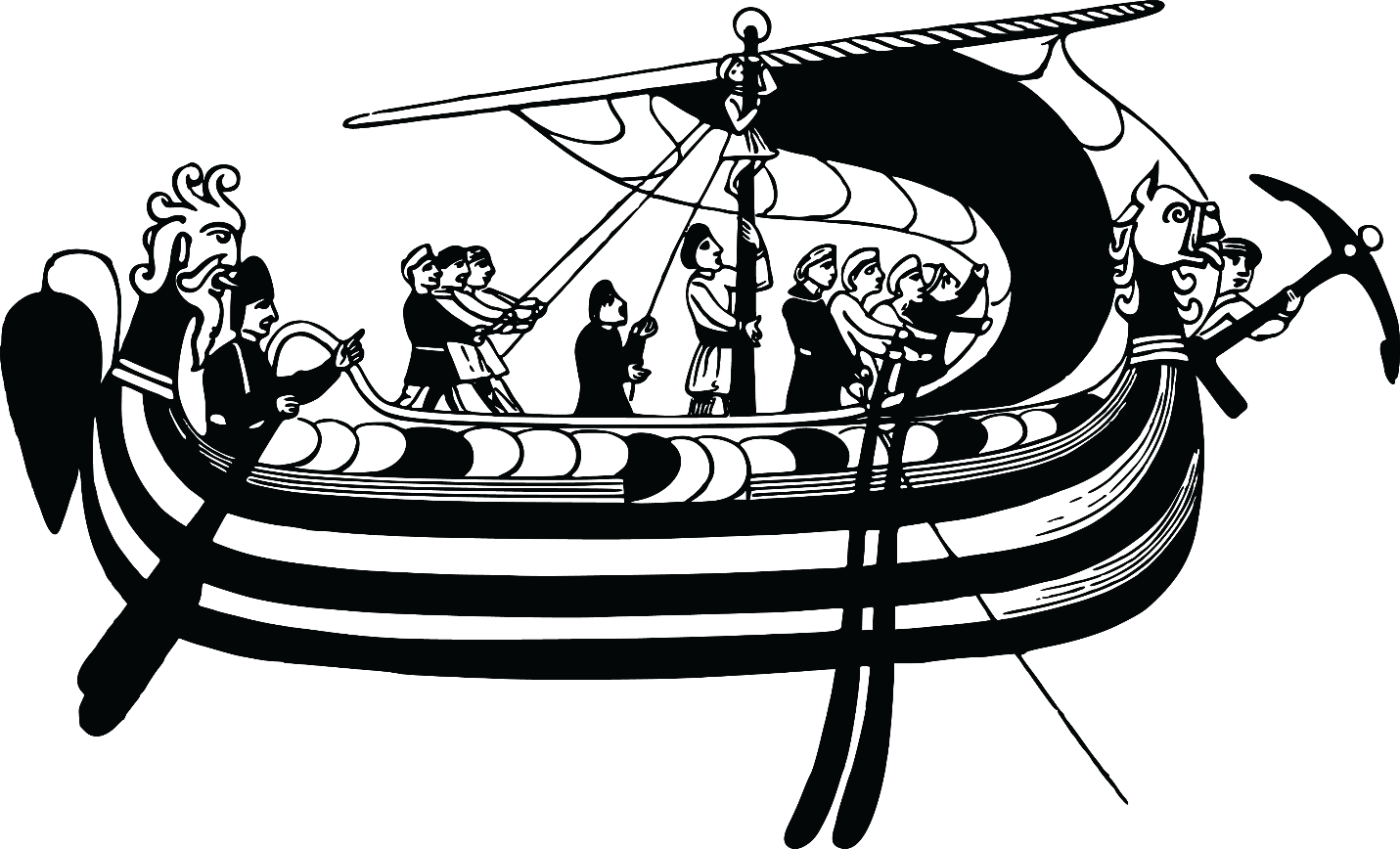

Metaphor

The metaphor that was chosen by the author is that of the ship and its crew. The workers form the hull of the vessel, and the management is the captain, which sets the course and gives instructions. The HR department is the crew of the ship, ensuring that the directions are carried out and that the hull of the vessel is well-cared for.

Personal Transition Critical Reflection

As I developed my critical analysis skills throughout the year, I became able to recognize the problems in my perception of human resource management. One crucial moment of change was the recognition that, while the directions that are provided by the administration are important, it is the task of human management to balance their implementation with the well-being of the workforce. Rather than view employees in an abstract manner as resources that have to be managed to achieve improved results, the HRM professional has to consider their positions and opinions. My participation in peer-assisted learning has helped me formulate this concept and refine it by adding the perspectives of other students. I am grateful to them for their assistance, as without it, I might have progressed considerably slower.

Throughout my work, I encountered numerous situations where I participated in cross-cultural groups. Their members displayed considerable variety in their places of origin, ethnicity, race and other aspects. They were also used to many different modes of business and practices and applied them in practice, providing a wide variety of suggestions. Many of these ideas were useful and contributed significantly to the success of the initiatives that we discussed. However, I also encountered challenges in team cohesion and cooperation. Coming from different contexts, some of the members were unfamiliar with the concepts proposed by others and skeptical of them. As a result, conflicts would emerge more often than in teams with less diversity and would often be challenging to resolve.

The concept of keeping a reflective diary resonated with me the most among the events that happened throughout the semester. I had rarely taken the time to consider my past performance before, and when I did so, I did it internally and relied on my perception. The feedback from an external source helped me refine the process, recognizing more of my shortcomings and working to address them. However, I regret my inability to visit the presentations that were given by several of the visiting speakers. They were prominent personalities and inspiration models, and their experiences would likely have been fascinating. I wish I could have visited those presentations, perhaps at the expense of some reading materials that were mostly supplemental to the information covered in lectures and seminars.

I believe that, on a personal level, I have transitioned to become a more competent HRM professional. I have obtained a new perspective that helps me understand my tasks and attain an overall improved performance. My growth as a team member has also been noticeable, as I have started taking a more prominent role in meetings and proposing ideas. I have become particularly interested in the CIPD module of performance and reward, as it pertains to my newfound understanding of employee importance. However, I struggled with service delivery and information, which was a convoluted aspect that involved extensive knowledge of all of the business’s stakeholders. In the future, I will attempt to address this gap while focusing on my strengths to become an excellent HRM professional.

PDP Report and Cost Plan

Reference List

Aoun, C., Vatanasakdakul, S. and Ang, K. (2018) ‘Feedback for thought: examining the influence of feedback constituents on learning experience’, Studies in Higher Education, 43(1), pp. 72-95.

Armsby, P., Costley, C. and Cranfield, S. (2018) ‘The design of doctorate curricula for practicing professionals’, Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), pp. 2226-2237.

Billett, S., Cain, M. and Le, A.H. (2018) ‘Augmenting higher education students’ work experiences: preferred purposes and processes’, Studies in Higher Education, 43(7), pp. 1279-1294.

Caspersz, D. and Olaru, D. (2017) ‘The value of service-learning: the student perspective’, Studies in Higher Education, 42(4), pp. 685-700.

Clarke, M. (2018) ‘Rethinking graduate employability: the role of capital, individual attributes and context’, Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), pp. 1923-1937.

Dundon, T. and Rafferty, A. (2018) ‘The (potential) demise of HRM?’, Human Resource Management Journal, 28(3), pp. 377-391.

Fillery-Travis, A. and Robinson, L. (2018) ‘Making the familiar strange – a research pedagogy for practice’, Studies in Higher Education, 43(5), pp. 841-853.

Fullana, J., et al. (2016) ‘Reflective learning in higher education: A qualitative study on students’ perceptions’, Studies in Higher Education, 41(6), pp. 1008-1022.

Griggs, V., et al. (2018) ‘From reflective learning to reflective practice: assessing transfer’, Studies in Higher Education, 43(7), pp. 1172-1183.

Guerci, M., et al. (2019) ‘Moving beyond the link between HRM and economic performance: a study on the individual reactions of HR managers and professionals to sustainable HRM’, Journal of Business Ethics, 160(3), pp. 783-800.

Guerci, M., Radaelli, G. and Shani, A.B. (2019) ‘Conducting Mode 2 research in HRM: a phase‐based framework’, Human Resource Management, 58(1), pp. 5-20.

Händel, M., Wimmer, B. and Ziegler, A. (2020) ‘E-portfolio use and its effects on exam performance – a field study’, Studies in Higher Education, 45(2), pp. 258-270.

Kianto, A., Sáenz, J. and Aramburu, N. (2017) ‘Knowledge-based human resource management practices, intellectual capital and innovation’, Journal of Business Research, 81, pp. 11-20.

Macklin, R. and Mathison, K. (2018) ‘Embedding ethics: dialogic partnerships and communitarian business ethics’, Journal of Business Ethics, 153(1), pp. 133-145.

Sugrue, C., et al. (2018) ‘Trends in the practices of academic developers: trajectories of higher education?’, Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), pp. 2336-2353.