Overview of the project

The West Gate Bridge Project Fundamentals case study is a comprehensive case that explores the course of managing projects and the procedures and processes therein. There are a number of fundamental issues that have to be adhered to in order to ensure the success of high scale and technical projects such as the West Bridge Project. Flaws in the course of managing such projects often create high chances of failure since they denote the lack of embrace of a number of vital technicalities that are critical for successful project completion.

The successful management of highly technical project requires adoption of clear procurement and supply structures that ensure successful sourcing of the desired expertise. Of greater importance in such a project is the technical capacity of the firms that are outsourced to complete the project. The technical capacity denotes high knowledge and skills in the contracted teams. This capacity is determined by the level of experience that is exhibited by the given firms. The other critical thing in such projects is the embrace of coordination in executing the project.

According to Gerardi (2011), a high degree of coordination has to be attained in the management of technical projects because of the fact that the work in such projects is of an incremental nature, marked by specialization of different teams in the discharge of certain tasks. As observed in the case of the West Bridge Projects, there were a number of flaws in the manner in which the project was managed. This is why technical problems were experienced in the course of the project, as denoted by the accident that was experienced on the 15th of October 1970.

Project fundamentals and issues of management

The West Gate Bridge is an engineering project that was designed to begin and accomplish the construction of a bridge to aid in the direct connection of the Western regions of Victoria and the Southern regions to the Central Business District of the Melbourne city in Australia. This project was very critical in as far as the advancement of transport and communication to and from Melbourne and the enhancement of economic activities in the region were concerned. Owing to the relevance of the project to Australians, there was the need to make sound considerations in the management of the project in order to fulfil the objectives of the projects.

The project was set to be accomplished within three years, commencing at the beginning of 1968 and completion of the project taking place in December 1970. This implies that the procedure of contract advertisement and awarding had to be done in an efficient manner to ensure that the work started in time in order to secure the set deadlines for the completion of the project. Adherence to the timelines of a project is important, yet it depends highly with the manner, accuracy and the speed with which the assignment of contracts is done by the core managers of the project (Wysocki 2012).

In the first instance, the negotiation with the government about the project was done by two companies, the Lower Yarra Crossing Company Ltd and later the Lower Yarra Crossing Authority. The first agreement was reached through the negotiation between the Lower Yarra Crossing Company Ltd and the government of Australia in 1964, where the government ascertained that the crossing was to take place through construction of a bridge; in this case the West Gate Bridge. In what can be termed as the first setback in the project, the first company that was involved in the negotiation of the project with the company, the LYCC, was disbanded barely a year after an agreement was brokered. The company was voluntarily liquidated.

The disbandment of the LYCC was not clearly explained and, perhaps, marked the possibility of setbacks in the entire projects process as it held the main goals and objectives of the project. This resulted in the formation of an independent body by the government, the LYCA, although still under the observance of the law since the LYCA was formed through an Act of Parliament. The main purpose of LYCA was overseeing the Bridge project by virtue of being the primary stakeholder in the project.

However, according to the prior stages of initiation of the projects, it can be argued that the LYCC would be suited to oversee the projects since it was the company that had the fundamentals of the projects. This would easily ensure effective management of the project. The level of independence in the newly formed Authority was compromised by the fact that it was underwritten by the state government through guaranteeing of all loans and debts by the LYCA (Melton 2008).

It should be noted that a number of interested companies as far as the construction of the Bridge is concerned had already consulted with the LYCC. An example is the Maunsell and Partners, a consulting engineering company that had been engaged in the project from the first stages of inception back in 1964. Therefore, establishing trust and a working relationship with the LYCC successor, the LYCA, was bound to be a daunting task, irrespective of the fact that the services of the company were automatically retained by the successor authority.

One of the most critical points in the progression of the project is the lack of capacity of Maunsell and Partners to cope with the project because of its magnitude. Maunsell and Partners openly doubted its capacity to cope with the project. This implies that it did not have the capacity to handle the project, yet it was on board as one of the main companies that were running the project. This is an indicator of a problem with the procurement process and the choice of the best suited companies to accomplish the project (The Value of Project Management, 2010).

According to the Project Management Institute (2010), capacity is one of the vital considerations in the choice of the top companies to be involved in the planning and implementation of a project. The failure of a project often begins with the failure of the core project managers to comprehensively assess the capacity of a company before putting it on board.

This is a strategic approach that ensures that the teams that are involved in the discharge of projects have the required level of competency that can enable them deliver on their roles. In addition, the relationship between the three major companies that were awarded contracts to undertake the construction was quite strenuous, an aspect that necessitated errors and inconsistencies in the project (Kendrick 2009).

Proposed structure and management of the project

Project planning and scheduling

According to BIS (2010), successful management of a project depends on the level of planning that goes into the structuring of the project. This entails bringing all the players into board and the ascertainment of the role of each player, accompanied with the assessment of the capacity of the stakeholders to deliver according to the standards and specifications made by the lead team, in this case the LYCA. In addition, it is critical for the team assigned with overseeing the project to be fully aware of the potential risks that can be encountered in the discharge of the project (Lester & Lester 2007).

In this case, the kind of risk that is encountered comes from unacceptable quality of work. This results in the collapse of the structure and the death of the people who were working on the bridge. This is a typical risk. Therefore, when discharging such projects the project managers should ensure that the engineering standards that are used in the project are of a desirable standard. As noted earlier, this depends on the ability of project managers to effectively outsource companies that have a resounding reputation in discharging such projects. Project standards and quality have to be adhered to at all costs. In addition, external factors such as the physical conditions on the given site lay soil and environmental conditions ought to be monitored in order to draw away the possibility of negative attributes of these features on the given project.

The first important consideration in the structuring of the project is scaling of the sub-projects within the main project. According to Pratt (2010), project scaling aids in the estimation of the required project inputs. The quantity and quality of project inputs guides in the selection of the firms that can deliver according to a given sub-project. This implies that the determination of the requirements is highly based on the scale that is established by virtue of pre-assessing the requirements of the project.

Project scaling, especially for technical projects like the West Gate Bridge Project is part of the process of prior planning and should come at the prior stages of the project before the selection of teams or companies to embark on real work (Turner 2000). The body that is responsible for overseeing the project has to ensure that it effectively solicits for highly qualified companies. These companies are then awarded the contracts to accomplish specific tasks (Lessard & Lessard 2007).

Project sourcing and procurement

What has come out strongly in the case is the lack of emphasis in clear procurement procedures. This has resulted in the failure to attain the best companies to help in the completion of the project. Project procurement is based on the results of the pre-assessment of the project, which is the basis upon which the technical standards of the project are determined and set. Project procurement in technical projects entails the establishment of the companies that have the required technical ability to complete certain sets of projects (Kerzner, 2013).

Each contract in the project has to be awarded according to a comprehensive assessment report about the companies that are competing for contracts (Westland 2007). Two critical things have to be given attention to in a technical project. These are the availability of technical skills and expertise and the ability of the company to avail the supplies that are required for construction. This ensures that delays are avoided in the process (Nicholas & Steyn, 2008).

The coordination of project

Project coordination ensures that the diverse roles that are played by the different companies involved are effectively implemented. According to American Society of Civil Engineers (2012), each company involved in the construction has to appoint key contact people who are responsible for ensuring that communication flows among all the players involved in different stages of the project.

According to Staples (2010), the coordination between project teams is best attained through control of the coordination process by the team that is responsible for overseeing the project. The coordination procedure between the teams has to be included in the project charter in order to align the project teams with the aspect of coordination for project continuity and successful completion (Meredith & Mantel 2012).

Monitoring and control of the project process is a key area in the management of civil engineering projects. This is one of the best modalities of ensuring that anomalies are easily detected in the course of the project.

Major Stakeholders in the project

Maunsell and Partners

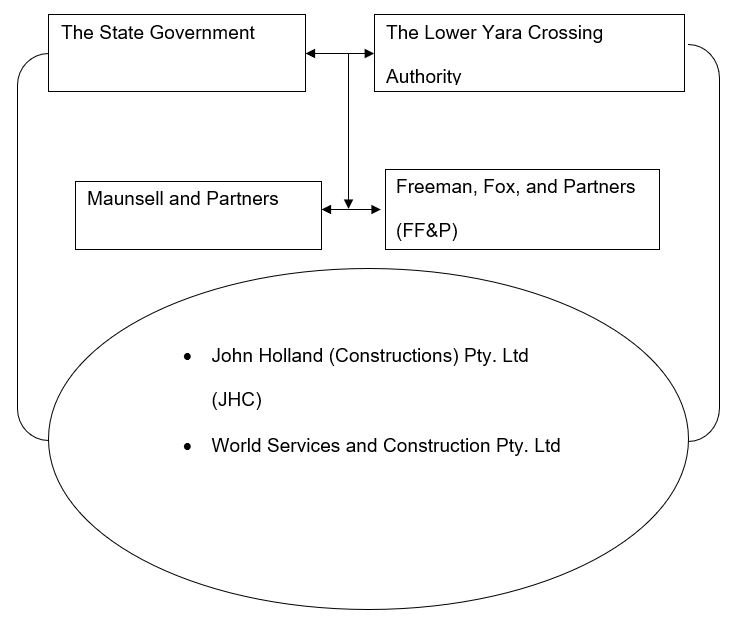

The State Government and the LYCA operate at the same level. The state government works closely with the LYCA to ensure that all the required resources are effectively procured or outsourced. Maunsell and Partners was one of the main consulting companies from the beginning of the project and was retained by the LYCA. In addition, Freeman, Fox, and Partners (FF&P) comes in at the same level with Maunsell and Partners because of the recommendation made by Maunsell to LYCA to deploy the company as an equal consulting partner. The other two companies, John Holland (Constructions) Pty. Ltd (JHC) and World Services and Construction Pty. Ltd, were contracted by the lead project managers.

List of References

American Society of Civil Engineers 2012. Quality in the constructed project: A guide for owners, designers, and constructors. American Society of Civil Engineers, Reston, VA.

BIS 2010. Guidelines for managing projects: How to organize, plan and control projects. Web.

Gerardi, B 2011. No-drama project management: Avoiding predictable problems for project success. Apress, New York, NJ.

Kendrick, T 2009. Identifying and managing project risk: Essential tools for failure-proofing your project. AMACON, New York, NY.

Kerzner, H 2013. Project management: A systems approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Lessard, CS & Lessard, J. 2007. Project management for engineering design, Morgan & Claypool Publishers, San Rafael, CA.

Lester, A & Lester, A. 2007. Project management, planning and control: Managing engineering, construction and manufacturing projects to PMI, APM and BSI standards, Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann, Amsterdam.

Melton, T. 2008. Real project planning: Developing a project delivery strategy, Butterworth-Heineman, Amsterdam.

Meredith, JR & Mantel, SJ. 2012. Project management: A managerial approach, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ.

Nicholas, JM & Steyn, H. 2008. Project management for business, engineering, and technology: Principles and practice, Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann, Amsterdam.

Pratt, D. 2010. Pragmatic project management: Five scalable steps to success, Management Concepts, Vienna, VA.

Staples, L. 2010. Project management: A technician guide, International Society of Automation, Research Triangle Park, NC.

The Value of Project Management. 2010. The value of project management. Web.

Turner, JR. 2000. Gower handbook of project management, Gower, Aldershot.

Westland, J. 2007. The project management lifecycle: A complete step-by-step methodology for initiating, planning, executing and closing a project successfully, Kogan Page, London.

Wysocki, RK 2012. Effective project management: Traditional, agile, extreme, Wiley, Indianapolis, IN.