Introduction

In this paper, it is argued that there is a strong relationship between business and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Underpinning this statement is the intrinsic relationship between business and society, which is an overriding theme in this report. In this regard, CSR is described as an inherent part of corporate strategic performance and to demonstrate the relationship, a case study of the Football Association of Ireland’s (FAI) adoption of socially responsible behaviour is provided. The evidence gathered from this assessment affirms the interdependence of CSR and business performance. However, before delving into the details of this analysis, it is important to review the relationship between business and CSR.

A Critique of the Relationship between Business and CSR

According to Lee, Ham and Koh (2019), CSR is a private initiative by businesses to be mindful of their impact on society. This philosophy promotes the idea that organisations need to think of their profit-maximization potential and ability to enrich communities as part of their core strategies. In this context of analysis, managers are encouraged to be cognizant of their organisations’ impacts on different stakeholders who support their operations, such as suppliers, customers, employees, communities and the environment (Gras-Gil, Manzano and Fernández, 2016).

The idea that businesses should exist for other purposes besides profit-making has existed for as long as industries have. Some common CSR models, such as stakeholder, institutional and legitimacy theories, which emphasise the need to address the non-economic impact of business operations, support this statement (Filho, 2019). For example, the stakeholder theory presupposes that companies should understand that their activities not only affect shareholders but other groups of people, such as employees and local communities, as well (Filho, 2019). Therefore, its proponents encourage managers to assess the impact of their business practices on these stakeholders as much as they would for their investors (Filho, 2019). The legitimacy theory also supports a similar idea by advancing the view that a company’s social acceptance stems from an unspoken contract it has with its members to be respectful of each other’s presence. In this regard, its proponents argue that a firm’s value system should be consistent with that of the society (Filho, 2019). The basic idea behind this view is that companies should not only maximise their shareholders’ profits but also add value to communities, which support their operations (Lee, Ham and Koh, 2019). In this regard, they are required to avoid pursuing business strategies that may harm communities (García-Sánchez, Aceituno and Domínguez, 2015). Several researchers, including Crane et al. (2017), Graafland and Smid (2019) support this claim by underscoring the relationship between business performance and CSR from an ethical perspective. Primarily, they argue that managers and employees should promote responsible business practices as corporate agents (Park and Elsass, 2017). This statement links ethical management with good CSR practices because responsible behaviours are associated with improved sustainability, profitability and responsibility for businesses (Morsing and Spence, 2019).

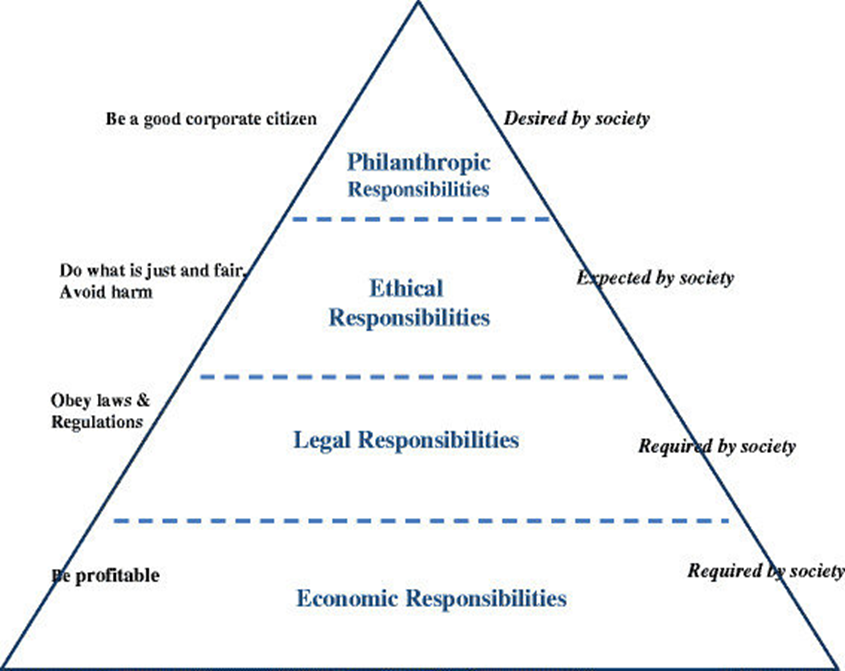

The relationship between corporate performance and CSR has highlighted a need to understand how socially responsible behaviours affect corporate governance. Researchers, such as Madueño et al. (2016), Rodriguez-Fernandez (2016), Gras-Gil, Manzano and Fernández (2016), have explored this relationship but their findings are unclear because financial performance is affected by several factors and is linked to different categories of CSR. However, Carrie’s CSR model has tried explaining the link between financial performance and socially responsible behaviours more directly using four main tenets of social responsibility: economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic. Figure 1 below shows how these parts are stratified.

According to the pyramid above, economic responsibilities are fundamental to CSR growth because all other functions depend on it. For example, companies that are profitable stand the best chance of weathering market storms because they can adopt mitigating measures, such as paying their employees on time, meeting financial obligations and contributing to the improvement of societal welfare, more quickly than those that have a weak financial position. In this regard, their economic abilities underline their CSR plans.

The second part of Carrie’s CSR model pertains to legal responsibilities. A company’s tax, health and safety requirements may be categorised here. The third tier of responsibilities in the CSR framework is a business’s responsibility to avoid harm. Lastly, philanthropic CSR initiatives are designed to foster responsible citizenship among companies. The relationship between CSR and financial performance stands at the lowest level of Carrie’s CSR theory – economic responsibilities. This is the link between CSR and corporate governance. However, the order of priority for pursuing linked CSR strategies depends on an organisation’s circumstances (Ghobadian, Money and Hillenbrand, 2015). This statement outlines the basis for reviewing CSR policies in the context of an organisation’s goals.

Promoting Sustainability and Organisational Goals

The link between CSR and business performance is highlighted in the potential for organisations to promote sustainable business practices, while pursuing their goals. Particularly, this statement is true for the manufacturing sector because failing to account for a company’s environmental impact may cause resource depletion and scarcity of organisational inputs. Similar to the inputs required by firms to produce goods and services, companies also need human resources to maintain their operations. Therefore, failing to improve employee welfare could lead to low levels of morale and productivity (Sharma and Tewari, 2018). Therefore, to be sustainable, firms need to appreciate the relationship between business performance and CSR with the assumption that the two concepts are interrelated.

The interconnectivity of business and social responsibility could promote a company’s overall performance because CSR is a competitive tool that firms can leverage in the market. Its adoption is supported by the growing awareness about the need for social responsibility in the corporate world (Beitelspacher and Rodgers, 2018). In this context of the discussion, the integration of business and social goals underlines a common purpose for establishing most businesses – to have a positive impact on society. Indeed, even primarily profit-driven organisations often strive to achieve this goal through their operational plans. Therefore, fundamentally, it is difficult to divorce business and social responsibility goals in the context of realising a business’s purpose, which is to serve other people.

The link between CSR and business performance is partly highlighted in the balanced scorecard technique, which encourages companies to assess the impact of their internal strategies and environmental variables on corporate performance. Aras (2016), Crowther and Seifi (2017) support this statement by demonstrating the important role played by the balanced scorecard technique in merging a company’s long-term and short-term goals. The model underscores the relationship between these two sets of goals because CSR embodies a company’s overall impact on society, while its daily operations are designed to realise the same vision using short-term measurement criteria. Therefore, the adoption of CSR practices in organisational models provides a framework for understanding how this balanced view can be achieved.

Stakeholder Engagement

A key tool explaining the interdependence of CSR and business performance is stakeholder engagement. It is based on a common understanding that successful socially responsible programs are based on people buy-in. Therefore, stakeholder engagement acts as a basis for promoting CSR growth (McCarthy and Muthuri, 2018). In line with this role, a key motivation for firms that have adopted CSR policies is to engage key stakeholders and make them aware of what they are doing to foster socially responsible behaviours (Asante et al., 2019). Stakeholder engagement acts as a platform through which they can do so because making people aware of ongoing CSR initiatives is a form of promoting a company’s image. Businesses can leverage such advantages to gain favour from the public.

Customers Socially and Responsibly Investing (SRI) in Organisations

Customers are key stakeholders in corporate management because companies strive to add value to their lives by developing products and services that appeal to them. Based on this relationship, there is a growing demand for companies to embrace better accountability, transparency and actionable strategies to address everyday social issues (Sajko, Boone and Buyl, 2020). This trend has been registered through changing consumer tastes and preferences, which has seen a surge in the number of people wanting to buy products from socially responsible companies (Sajko, Boone and Buyl, 2020). Therefore, customers prefer to invest in organisations that have a strong CSR policy because they believe these entities care for them.

Attracting Capital Markets to the Business

Investors around the globe control the movement of capital from one market to another. They play a pivotal role in the normal functioning of business operations because they regulate capital flow, which is a major factor of production. In line with its importance, investors prefer to allocate financial resources to companies that have strong CSR policies because such an action is indicative of transparent business practices (Beitelspacher and Rodgers, 2018). This way, they are more likely to trust the financial reporting procedures and performance indices of such corporations better than they would a company that does not support CSR. Consequently, socially responsible businesses attract more capital from investors compared to those that do not have a similar policy.

Link between CSR and Financial Performance

The relationship between CSR and financial performance partly manifests through the environmental, social and governance criteria (ESG), which allows investors to channel resources to companies that share similar values. The section below explains how to meet the ESG criteria.

Attaining ESG Criteria

FAI, being a sports organisation, should be motivated to meet ESG criteria by doing what is right and fair. However, the association’s poor financial performance has made it difficult to adopt new CSR policies or guidelines that would strain its financial resources. Therefore, to protect its economic and shareholder interests, the association should adopt policies that augur well with its existing financial and administrative structures. These policies should also be centred on promoting CSR initiatives and developing partnerships.

Partnerships

There are three main techniques for meeting CSR objectives for sports organisations, such as FAI: in-house project development, outsourcing and partnerships. FAI needs to pursue the latter framework because it could extend the organisation’s network outreach and community impact. In line with this approach, Lee, Heinze and Lu (2018) say the most commonly launched CSR partnerships in sports involve the promotion of youth activities, discussion of health initiatives, community development and charitable giving. Broadly, these CSR initiatives are either environmental or social in nature. FAI’s CSR implementation strategy should be social because it mainly focuses on the promotion of community goals and objectives, such as diversity management, health promotion, peace development and reconciliation. Therefore, its partnership model should be centred on seeking local support from well-meaning partners.

FAI should also seek partnerships that allow it to develop a strong grass-root appeal when implementing its social plans because CSR is essentially a community-based concept (Sajko, Boone and Buyl, 2020). For example, the association could enhance its partnerships with Green School, Healthy Ireland, and Active Schools Campaigns to strengthen its grass-roots appeal. Similarly, FAI may collaborate with the League of Ireland to expand its local presence because the latter has a significant community presence in most major towns in the nation. Such initiatives may have a strong long-term effect on society because when children are taught the importance of environmental conservation, sports and good health, they are likely to implement the same skills as adults. Therefore, they need to be made aware of how they should synchronise the benefits and goals of CSR in their personal lives and work to create a holistic framework of achieving social and economic objectives. For FAI, this strategy will create a synergy of purpose between the organisation’s sporting and community-based objectives.

The most important feature of this implementation plan is its customisation potential because a one-size-fits-all approach cannot work for all communities that FAI operates in, as each one may have unique needs. Therefore, FAI and its partners should only support community programs through secondary contributions, while leaving community leaders to take a more aggressive and proactive stance in the advancement of common objectives, as proposed by Malik et al. (2020). For example, a “Green Garden” could focus on one side of its main sports pitch to sensitise people about the need for innovation and conservation. Similarly, FAI could sponsor programs that give nutritional advice to community members to promote their health. Such action provides a basis for integrating the firm’s identity in the lives of its fans and the host community.

Promotion

FAI should promote its CSR programs because it has received little visibility throughout the years. The organisation’s poor CSR record partly stems from management’s failure to communicate current socially responsible operational guidelines, such as its policy structure, which is centred on the need to achieve four key pillars of CSR policy: community, responsible sourcing, environment and people. Consequently, there has been low morale among some of FAI’s employees regarding the uptake of socially responsible practices.

By promoting its programs and initiatives, FAI would not only be letting the public know about its current efforts at promoting CSR but also inform them about plans of advancing the same cause. Complementing this strategy should be a branding framework that encourages every child that owns a premier league T-shirt to have an Ireland Jersey as well. This strategy will make sure that there is extensive brand visibility at least within every home that has a football fan. However, it should be contextualised within the purview of the areas that FAI would have the highest impact, as it cannot compete with premium league actors. For example, it should launch its CSR strategies using platforms that have strong grassroots support, such as the FutBol Cs Para Los Vivos. Indeed, the average local child cannot go to Anfield to watch a major league game, but he or she can watch a local game at a local and accessible location, such as Oriel Park. Therefore, promoting FAI’s CSR initiatives locally would have the greatest impact on the community.

Attracting Investments for Business Sustainability

Macro Perspective

The development of CSR initiatives in the corporate sector has affected sports organisations and entities in different ways. For example, it has forced some of them to adopt organisational structures similar to those of big multinational corporations (Lee, Heinze and Lu, 2018). From a macroeconomic standpoint, most professional sports clubs should adopt ESG criteria that are similar to those of mid-size firms because they are designed to enhance value capacity, which is necessary to realise CSR goals (Lee, Heinze and Lu, 2018). Relative to this statement, FAI’s CSR plan should be hinged on a broader collaborative framework that is spearheaded by a global body, such as the Federation of International Football Association (FIFA) or a United Nations (UN) agency, such as the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). This recommendation is in line with common practice in the sports sector whereby the activities of football associations are integrated with those of a larger social cause, such as saying no to racism in sports (Lee, Heinze and Lu, 2018). For example, FC Barcelona supports UNICEF’s projects by allocating a percentage of its budget to this cause.

This strategy emanates from a larger group of economic-based theories, which emphasise the need to address a company’s economic interests in CSR. Usefulness, agency and political accountability frameworks fall within this category of theories (Filho, 2019). For example, the political accountability theory presupposes that CSR activities should be centred on two primary parties: the one who provides resources (individuals) and the organisations that receive them (Filho, 2019). This theory further goas ahead to dissect managerial behaviours according to accounting practices designed to achieve specified outcomes (Filho, 2019). For example, an organisation can choose accounting practices that promote shareholder value over those that prioritise environmental concerns to attract more capital from investors. Similarly, a non-profit organisation can choose to adopt accounting policies that promote the “common good” as opposed to those that have an economic appeal. The type of practice chose depends on the desired organisational goal. FAI should attract investments for business sustainability by adopting accounting policies that appeal to investors’ needs.

Micro Perspective

At the community level, FAI has a policy for participating in community development by supporting the activities of existing networks of agencies, people and community leaders who use sports to address social issues. For example, using this operational framework, FAI supports social initiatives aimed at addressing the plight of communities in disadvantaged areas. It has also committed itself to work with special interest people, such as disabled people, who are typically ignored in mainstream community programs. A key inspiration of FAI’ CSR policy agenda is the recognition that everybody should be given a chance to participate in sports, irrespective of their status, gender or social positioning. In line with this vision, FAI has received acclaim for its CSR initiatives, such as the Sports industry Award and the FAI/HSE Kickstart 2 Recovery Mental Health Outreach Programme Award, which recognised the association’s contribution towards the promotion of good mental health among the youth.

However, its leadership has not promoted these achievements well enough in the local community to attract investments for business sustainability. The lack of managerial seriousness manifests in the association’s failure to review its CSR policies from 2013. This laxity means that its CSR implementation policies remain cosmetic, as they are not properly integrated into the organisation’s operational plans. This leadership gap has created a void in the implementation of the organisation’s CSR policies. Particularly, the mismatch in CSR planning and implementation is more profound among low-level workers because they are unaware of how their activities contribute towards the realisation of these objectives. This problem may be symptomatic of their failure to recognise the importance of CSR objectives in the company’s leadership structure. Nonetheless, promoting the organisation’s achievements through local partnerships would see it garner the interest of community partners in advancing its CSR objectives. Management needs to spearhead this process.

Conclusion

The link between business and society has been demonstrated in this report through the case study investigation of FAI. The recommendations provided here are largely consistent with those of previous researchers who have affirmed the importance of CSR in corporate governance. Therefore, in the long-term, the link between business and society will continue to shape the corporate strategies of several companies as a growing number of consumers and governments become increasingly aware of the need to adopt a holistic business model for meeting a company’s goals by catering to the needs of all stakeholders. Therefore, it is likely that organisations, such as FAI and its partners, will continue to adopt policy guidelines that promote social responsibility. Overall, by following some of the proposals highlighted in this report, FAI can strengthen its brand by promoting itself as a socially responsible organisation.

Reference List

Aras, G. (2016) A handbook of corporate governance and social responsibility. London: CRC Press.

Asante, E. et al. (2019) ‘Let the talk count: attributes of stakeholder engagement, trust, perceive environmental protection and CSR’, SAGE Open, 9(1), pp. 1-10.

Beitelspacher, L. and Rodgers, V. L. (2018) ‘Integrating corporate social responsibility awareness into a retail management course’, Journal of Marketing Education, 40(1), pp. 66-75.

Crane, A. et al. (2017) ‘Measuring corporate social responsibility and impact: enhancing quantitative research design and methods in business and society research’, Business & Society, 56(6), pp. 787-795.

Crowther, D. and Seifi, S. (eds.) (2017) Modern organisational governance. London: Emerald Group Publishing.

Filho, W. L. (ed.) (2019) Social responsibility and sustainability: how businesses and organizations can operate in a sustainable and socially responsible way. New York, NY: Springer.

García-Sánchez, I. M., Aceituno, J. V. F. and Domínguez, L. R. (2015) ‘The ethical commitment of independent directors in different contexts of investor protection’, BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 18(2), pp. 81-94.

Ghobadian, A., Money, K. and Hillenbrand, C. (2015) ‘Corporate responsibility research: past-present-future’, Group and Organization Management, 40(3), pp. 271-294.

Graafland, J. and Smid, H. (2019) ‘Decoupling among CSR policies, programs, and impacts: an empirical study’, Business & Society, 58(2), pp. 231-267.

Gras-Gil, E., Manzano, M. P. and Fernández, J. H. (2016) ‘Investigating the relationship between corporate social responsibility and earnings management: evidence from Spain’, BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(4), pp. 289-299.

Lee, S., Ham, S. and Koh, Y. (2019) ‘Special issue on economic implications of corporate social responsibility and sustainability in tourism and hospitality’, Tourism Economics, 25(4), pp. 495-499.

Lee, S. P., Heinze, K. and Lu, L. D. (2018) ‘Warmth, competence, and willingness to donate: how perceptions of partner organizations affect support of corporate social responsibility initiatives in professional sport’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 42(1), pp. 23-48.

Madueño, J. H. et al. (2016) ‘Relationship between corporate social responsibility and competitive performance in Spanish SMEs: empirical evidence from a stakeholders’ perspective’, BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(1), pp. 55-72.

Malik, F. et al. (2020) ‘Determinants of corporate social responsibility related to CEO attributes: an empirical study’, SAGE Open, 10(1), pp. 1-10.

McCarthy, L. and Muthuri, J. N. (2018) ‘Engaging fringe stakeholders in business and society research: applying visual participatory research methods’, Business & Society, 57(1), pp. 131-173.

Morsing, M. and Spence, L. J. (2019) ‘Corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication and small and medium-sized enterprises: the governmentality dilemma of explicit and implicit CSR communication’, Human Relations, 72(12), pp. 1920-1947.

Park, J. and Elsass, P. (2017) ‘Behavioral ethics and the new landscape in ethics pedagogy in management education’, Journal of Management Education, 41(4), pp. 447-454.

Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. (2016) ‘Social responsibility and financial performance: the role of good corporate governance’, BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(2), pp. 137-151.

Sajko, M., Boone, C. and Buyl, T. (2020) ‘CEO greed, corporate social responsibility, and organizational resilience to systemic shocks’, Journal of Management, 9(2), pp. 1-10.

Sharma, E. and Tewari, R. (2018) ‘Engaging employee perception for effective corporate social responsibility: role of human resource professionals’, Global Business Review, 19(1), pp. 111-130.