Abstract

This study is focused on understanding the educational experiences of Chinese and UK students who participated in educational tourism. Data was gathered using the triangulation method, which allowed the researcher to collect information from interviews, questionnaires (n=112) and secondary research data. These three centres of information were integrated complementarily, whereby the weaknesses of one technique could be remedied by the strengths of another in a broader mixed methods framework of analysis. Relative to these areas of discussion, it is observed that there is not much difference in the educational experiences of both Chinese and British students.

This similarity stems from the standardisation of education programs between both countries. However, differences in culture and educational policies between both sets of respondents have significantly impacted how students perceive their learning experiences. For example, it was observed that UK students were often concerned about integrating themselves in the local Chinese culture but the same approach was not openly embraced by the Chinese. Such differences in attitudes exemplify the need to understand how they influence their perception of educational tourism.

Introduction

Background

The concepts of education and tourism come from diverse disciplines of study but researchers have recently used them to highlight the growing globalisation of educational services (Ma & Garcia-Murillo 2017; Simola 2014). According to Schatz (2016), education refers to a set of systemic procedures aimed at influencing how people think. Therefore, the concept refers to a mind training process and an important aspect of human development because it brightens people’s minds by imparting them with new knowledge (Ma & Garcia-Murillo 2017; Simola 2014). Educational tourism stems from this definition and it refers to the ability of students to cross international borders to pursue various learning objectives.

According to Simola (2014), educational tourism attracts more than 1,000,000 students annually and supports a total global spending of about $6.2 trillion in the higher education sector. Relative to these statistics, Ma and Garcia-Murillo (2017) estimate that about 540,000 international students have chosen the United States (US) as their preferred educational tourism destination. In Western Australia, about 20,000 such students have come from different parts of the world to reside and learn in various institutions of higher learning as well (Schatz 2016). This population accounts for about $430 million in domestic expenditure within the country (Schatz 2016).

Based on the significance of educational tourism to local economies, this type of travel is regarded as a key part of the global tourism market (Simola 2014). The growth witnessed in the sector has emanated from globalisation and the spread of the internet which supports the development of this specialised area of tourism. Relative to this assertion, Krishna (2018) says that technological developments made in communication, transportation and information processing are some of the key drivers of this trend.

Krishna (2018) says that travelling to a foreign destination to access educational services is an old concept and has been practiced for centuries. This type of travel has been embedded in the traditional concept of tourism because, by virtue of its nature, people tend to learn a lot from visiting new places and orienting themselves with different social, economic and political issues associated with other societies.

This understanding of tourism, when merged with the concept of education, creates the need to understand its implication on higher education because both concepts are broad and encompass multiple aspects of educational services. For example, Ma and Garcia-Murillo (2017) says that educational tourism could include a range of concepts, such as travel for general interest learning and participating in purposeful school trips.

Schatz (2016) says that students who participate in educational tourism also experience different types of learning experiences. The two major types of educational tourism experiences include those organised independently and those designed to appeal to organised forums (formal discussions) (Schatz 2016). The existence of divisions in the methods of learning highlighted above show that not only are there disagreements in how students experience their learning processes but also that there are different mechanisms through which the same experiences could be disseminated.

Research Problem

The growing appetite for educational tourism in China has seen the country send about 450 students to different locations or destinations around the world to get an education (Schatz 2016). The United Kingdom (UK) and the US remain the top destinations for educational tourism in China. The two countries are also regarded as the leading summer vacation destinations in the world (Schatz 2016). Nonetheless, Australia, Canada and Singapore are other attractive destinations for educational tourism in China. Despite the existence of significant differences in culture and educational polices between China and the UK, few researchers have bothered to understand how such variances impact the experiences of learners when they participate in overseas field trips.

The UK and China are among the world’s leading educational tourism markets but both of them have been incubated over different periods. This difference in developmental periods has led to the development of different outcomes for the students involved. For example, as Liu and Schänzel (2018) point out, educational tourism is a core part of western educational dogma but the same argument is inapplicable in China because educational tourism is a recently adopted concept (Liu & Schänzel 2018). For example, the earliest forms of education tourism in the country happened in the late 1980s and they were aimed at expanding Confucianism (Liu & Schänzel 2018).

The need to understand differences in the experiences of educational tourism between the UK and China also stem from the increasing number of Chinese students in the UK who are making an important contribution to the British economy through increased expenditure, particularly in the higher education sector. Furthermore, many British university students are interested in understanding the Chinese culture and want to study and travel to the communist nation. These learning motivations explain why there is a need to understand the educational experiences of students who take part in educational field trips organised in both countries.

Aim and Objectives of Study

The aim of this dissertation is to investigate the experiences of Chinese and British university students’ participation in educational tourism. The goal is to make a comparative analysis between the experiences of the two sets of students and discuss problems in the Chinese educational market that could be solved through the formulation of interventions that increase the participation rate of Chinese university students in this segment of travel. Key objectives guiding this research are provided below.

- To investigate trends defining the participation of Chinese and British university students in educational tourism.

- To investigate internal conditions, such as students’ willingness and motivation to travel, affecting Chinese and British university students’ participation in educational tourism.

- To investigate the external conditions, such as social conditions and legal systems, affecting Chinese and British university students’ participation of educational tourism.

- To discuss problems emanating from perception, policy, law, economy and other aspects of Chinese university students’ educational tourism that may need to be improved to enhance educational outcomes.

Importance of Study

Stemming from the background and definition of educational tourism highlighted in this chapter, this paper highlights the feasibility and need to undertake a comparative analysis of educational tourism between Chinese and British university students to improve its market in both countries. Relative to this assertion, the goal of undertaking this research review is to improve the market for educational tourism by promoting the exchange of learning programs between university students from the UK and China. Therefore, the difference in educational tourism between these two countries can promote the development of educational tourism for both countries.

The subsequent section of this document is the literature review part, which contains an analysis of what other researchers have written or said about the research topic. It provides the foundation for the research process by outlining a basis for comparing current with historical data. The second part of the paper will be the methodology section. It shows that data was collected using three techniques: interviews, questionnaires (primary research) and published data (secondary research). The interviews were used to verify and compare the questionnaire findings, while secondary research data was used to compare the findings with existing information.

The questionnaire was administered to a group of 112 respondents who were recruited using the stratified purposeful sampling technique. Interview data was recorded with the informant’s permission and the data analysed using the thematic and coding method. Comparatively, quantitative data was analysed using SPSS and Microsoft Word 2013 Software. The fourth chapter of this paper presents the findings obtained from the implementation of the methods highlighted above. A discussion of the same findings is provided in the fifth chapter and the last section of the study provides a summary of the findings and outlines specific recommendations that could be adopted in the UK and China to improve educational tourism.

Literature Review

Introduction

This section of the report contains a review of previous research works that have explored the study topic. Particularly, the articles sampled in this review highlight the role of student attitudes towards educational tourism, differences in law between the UK and China, their impact on educational programs and the effects of high costs of education on educational tourism.

However, before delving into the details of these areas of analysis, it is vital to note that this literature review is contextualised within the main tenets of the research questions, which focus on investigating trends in Chinese and British educational tourism, understanding the effects of intrinsic factors (such student motivation) on educational tourism, examining the role of external conditions, such as social conditions and legal framework, on educational tourism in China and the UK and identifying possible solutions that would improve educational tourism standards in the United Kingdom (UK) and China. The first area of analysis centres on understanding the attitudes of Chinese and British Students towards educational tourism.

Attitudes of Chinese and British Students towards Educational Tourism

Educational tourism is partly a product of student attitudes towards learning and their experiences in the classroom setting (Muthanna & Miao 2015). However, this area of research has been poorly explored because of the inadequacy of research studies to understand its implicit attributes, such as student motivation. However, overriding this concern is the belief that seeking overseas education would improve the learning outcomes of students who engage in educational tourism and by extension, the opportunities to advance their careers (Özoğlu, Gür & Coşkun 2015). These beliefs and perceptions about learning could be influenced by several factors relating to the learning environment but culture is deemed one of the primary forces of influence (Gavin 2018; Yuan 2018).

Culture affects student perceptions about educational tourism, including what they deem useful to their educational pursuits, or not (Gavin 2018; Yuan 2018). Although largely seen to be positive, student attitudes encompass different emotions relating to the learning process, including their behaviours and values (Muthanna & Miao 2015). In turn, their thinking patterns and behaviours are influenced by the same force (culture) and their learning outcomes shaped through their interactions with it. Based on the influences of these attitudes on student learning outcomes, the success of educational tourism largely depends on the beliefs about travelling abroad to seek quality education, as opposed to the acquisition of specific knowledge that relates to it (Gavin 2018; Yuan 2018).

Several research studies have pointed out that students’ attitudes could significantly affect the outcomes of educational tourism by influencing the willingness of learners to acquire new knowledge and respond to associated challenges (Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). Therefore, their level of engagement and interest in educational tourism could be significantly affected by the same factors. Without a personal initiative to learn, it is increasingly difficult for students to perform well in any capacity of educational tourism (Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018).

While positive attitudes could empower students to take bold steps in promoting their educational tourism goals, negative attitudes also have the same effect because they make students fearful and anxious about studying in foreign lands (Landon et al. 2017; Siraprapasiri & Thalang 2016).

Consequently, they are prevented from witnessing the rich experiences of learning broad and are inhibited from using any of the tools that would improve their learning outcomes (Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016). In line with this view, studies have shown that students who suffer from negative attitudes about educational tourism often exhibit diminished morale, boredom, or low levels of participation in educational tourism (Landon et al. 2017; Siraprapasiri & Thalang 2016).

In this context of analysis, it should be noted that negative student attitudes not only prevents students from enjoying the benefits of educational tourism but also discourages those who have the ability to do so from enjoying the same benefits because of their inability to use their full capabilities. Research studies have also shown that the opposite is true because students who have a positive attitude towards educational tourism are easily engaged in the process of learning and motivated to excel in it because they find the linked learning processes enjoyable or valuable to their foreign learning experiences (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

For example, research studies have explored how the attitudes of Chinese students towards learning in English influence their learning experiences and willingness to participate in educational tourism (Lu, Woodcock & Jiang 2014; Zhai, Gao & Wang 2019). Therefore, those who have a positive attitude towards learning English have a higher probability of engaging in educational tourism compared to those who have a negative attitude. Again, as highlighted in this document, such differences are intrinsic and may vary across different jurisdictions or even personalities.

A study by Yuan (2018) and Bislev (2017), which investigated student attitudes about cultural themes, suggested that most Chinese students were willing to learn about their cultural themes first before international ones. This view highlights the quest by Chinese students to seek their own local understanding of education before attempting to understand an international one.

For example, attitudes towards English learning are deemed to align with international standards for developing education curriculum because of its global nature (Lu, Woodcock & Jiang 2014; Zhai, Gao & Wang 2019). Therefore, those who are interested in learning the language have better chances of succeeding in educational tourism compared to those who do not (Lu, Woodcock & Jiang 2014; Zhai, Gao & Wang 2019).

Studies that have explored the attitudes of Chinese and British students towards educational tourism suggest that there are more commonalities among both sets of students than there are differences in their attitudes towards educational tourism (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

For example, a study by Cozart and Rojewski (2015) showed that both groups of students liked beach holidays and preferred to relax after school by engaging in recreational activities. In this regard, both sets of students do not view educational tourism as a pure learning process but also an opportunity for recreation. Studies have also shown that both British and Chinese students are enthusiastic about visiting and learning in new environments or taking part in the local culture of foreign communities (Lin 2019; Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018).

Alternatively, some studies have shown that there are significant differences between the British and Chinese students regarding their intentions to participate in educational tourism (Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

Notably, it has been observed that the Chinese are interested in learning about other cultures and visiting historical sights, while their English counterparts look forward to enjoying recreational activities and having fun through educational tourism (Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). These differences are seen to supersede gender differences because they are rooted in long-standing cultural beliefs associated with eastern and western lifestyles (Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

Differences in Law and their Impact on Educational Tourism among Chinese and British Students

Different countries have unique legal systems that affect different aspects of their social, political and economic growth (Guo, Li & Yu 2017). Particularly, there is a difference in the manner western and Eastern countries, such as China, design their laws and use them to further their educational agenda (Cozart & Rojewski 2015). These laws significantly influence different areas of educational tourism, including travel, visa status and even residency programs (Guo, Li & Yu 2017).

The Chinese law is based on Confucianism and it emphasises the need to respect the morality of legal actions more than the law that underpins it (Anshu, Lachapelle & Galway 2018). This line of reasoning discourages authorities from imposing strict judgements or harsh punishments on offenders and instead encourages them to reform, as a more permanent way of instituting change not only in education but also other aspects of life as well. In this regard, the Chinese believe that the administration and adjudication of laws touching on different aspects of educational tourism need to be analysed through a moral but not a legal lens (Zhang & Lovrich 2016).

Stated differently, the realisation of social order is best achieved through moral persuasion, as opposed to the implementation of legal clauses of law (Anshu, Lachapelle & Galway 2018). Therefore, the law is there only to complement the process of educational tourism and not to initiate it or be an end unto itself. Again, this application of law stems from Confucianism, which emphasises the need to maintain strong social relationships in the society (Cozart & Rojewski 2015). Each type of relationship between a person of authority and his or her subjects (say a father and son) has its own unique merits and context that has to be respected when exercising principles of law.

It is important to understand the implications of law when analysing educational tourism between China and the UK because they have a strong implication on existing policies about travel, residency and the development of educational curriculum (Byrne 2017). For most parts of the last two decades, both China and Britain have made significant changes to their Legal systems to encourage international students to seek education services in their countries (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018).

For example, the UK recently announced a change in its law to allow foreign students who have graduated from local universities to stay in the UK for up to two years (Tuner 2019). Previously, they were only allowed to stay for four months after graduation (Tuner 2019). The move is speculated to be aimed at increasing the demand for education by international students (Tuner 2019).

Visa stipulations affecting international students in the UK are only a small part of the wider sets of laws that students have to comply with before coming to the country. For example, students are required to uphold immigration checks and meet the minimum entry grade requirements for each university or course (Chankseliani 2018). China also has similar laws although its regulations are designed to appeal to the mainstream philosophies of the Chinese government and people (Kubat 2018).

For example, it is mandatory for internationals students to study some aspect of Chinese culture when they enrol in a local university (Lang 2018). China’s laws also prohibit foreign students from engaging in political activities whenever they are in the country. Therefore, students have to only focus on completing their learning programs and stay away from the political systems of the country.

Observers say that some of the legal guidelines described here attempt to create a stronger or firmer political and ideological control over the teaching and learning processes undertaken in China (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018). The trend has been on-going for a long time and it is informed by the view that some Chinese universities have been operating without much control from the government. In line with this view, there is a consensus among many researchers who have investigated China’s laws on education that the country prefers a legal system that aligns with the current political ideologies of the state (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018).

However, a broad overview of the country’s laws shows that China has emphasized a lot on culture and language. This is why before admission to some courses, students are required to study some aspects of the Chinese culture.

Although legal changes in Britain and China have made it possible for students from both countries to access international education, some policies have not been fully implemented. Consequently, China has instituted several legal reforms to promote the growth of the sector, including education tourism (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018). This is why several provinces and jurisdictions still have the leeway to institute additional laws to facilitate educational tourism (Chankseliani 2018). For example, the city of Xi’an allows for tax exemptions to international students who seek education in private universities because the government planned to encourage such higher institutions of education to improve the quality of their education and make it world class (Kubat 2018).

Differences in Educational Costs between Britain and China and their Impact on Educational Tourism

The cost of education has gained prominence in academic circles within the past three decades. Many literatures that have delved into this area of analysis have used different concepts, such as economies of scale and cost structures to explain the impact of higher education costs on student learning outcomes (Schneider & Deane 2015). These discussions have also been conveyed within the general need to improve resource allocation in the higher education sector (Schneider & Deane 2015; Courtney 2019).

The importance of understanding the impact of educational cost structures on student learning outcomes has also been pegged with discussions surrounding the growth of educational tourism because the concept is impacted by the willingness of students to seek affordable educational opportunities overseas (Courtney 2019).

Although the cost of education in Chinese universities is relatively standardized, there is a lot of variation to the amount of money students can pay to access education services in private universities (Schneider & Deane 2015). Comparatively, the cost of education in the US is significantly higher than China. A report by Merola, Coelen and Hofman (2019) suggests that the difference could be more than 50%. The lowest tuition fees paid in US public universities is about $1,500 per year but the average tuition fees is $6,500 for private institutions of higher learning (Kyungpook National University 2019). In some cases, this number could be as high as $9,000 for some universities (Kyungpook National University 2019).

The low tuition costs linked to public universities are often associated with 2-year courses as opposed to 4-year learning programs that take more time to complete and assess (Kyungpook National University 2019). Overall, tuition costs in public universities in the US are significantly lower than those in private universities (Courtney 2019). The tuition fees paid by non-resident students is also significantly high because there is an additional residency fee that foreign students have to pay to authorities (Kyungpook National University 2019). Resident students do not have to pay for this cost.

Cost is often a significant consideration for most foreign students in the US an China because they have to think about tuition and accommodation costs when studying abroad. These concerns have been further extended to the need to understand the future of education because issues about quality and inefficiencies of education services have increased the impetus to understand why cost is an important consideration in promoting educational tourism and sustainability (Schneider & Deane 2015; Courtney 2019).

The problem is not only confined to the education sector because people generally have concerns regarding the implications of an expensive education system on the ability of students to get quality services (Courtney 2019). In the US, such discussions have been contextualised in debates surrounding rising levels of student debt. Similar discussions have been had in the UK (Courtney 2019).

Relative to the above discussions, the revenue theory of cost, as developed by Howard Bowen in the 1980s, has been used to explain financial trends in higher education (Schneider & Deane 2015). This theory suggests that higher institutions of learning often spend most of the resources they have on on-going projects and have little to save (Schneider & Deane 2015). Therefore, whenever, they receive increased resource allocations, their costs also escalate, thereby creating a spiral effect of income and expenditure (Schneider & Deane 2015).

Decades that have seen the application of this theory in practical educational contexts show that many countries have systems that create a strong need for seeking financial resources, which are later absorbed into different school programs that equally demand a lot of money to run (Schneider & Deane 2015).

To address some of the above-mentioned concerns, many countries that have a vibrant education sector are paying attention to education tourism because it helps to boost their economies and improve their existing infrastructure networks (Lee, McMahon & Watson 2018). Doing so generates revenues for the travel industry and indirectly leads to the assimilation of different cultures, thereby makings students more dynamic and responsive to multicultural issues (Lee, McMahon & Watson 2018).

Although educational tourism is widely welcomed by many countries, it only serves a small niche market in tourism and education sectors. The uniqueness of this market means that few researchers have focused on understanding how it works in educational tourism or why students are motivated to travel across borders to get an education. One discourse that has emerged from this investigation is the need to understand the true meaning of the context of analysis.

Studies show that the cost of higher education in China is significantly lower than the UK (Kyungpook National University 2019; Thøgersen 2015). However, the cost of education in China is higher than some European countries (Hahn 2015).

In line with this discussion, it is important to acknowledge that the low cost of education in China is not felt in all parts of the country because the tuition fees associated with pursuing an education in major cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, is significantly higher than other parts of China (Zhou 2018). The competitiveness of the college admission process in China is part of the reason why some Chinese students leave the country and seek new opportunities for higher education overseas (Hansen 2015). Those that secure a spot in these foreign universities are often forced to pay high tuition fees which could be prohibitive to some people.

Thøgersen (2015) says that analysing the cost of education between China and western countries should be done after acknowledging the cost of living as well. Relative to many western countries, including the US and UK, the cost of living in China is significantly lower than most western countries (Chen & Ross 2015). Therefore, students who study overseas may experience challenges adapting to new expenses. This change in living costs has been prohibitive for many Chinese families who come from low income households.

A report by Courtney (2019) suggests that the cost of education in the UK is significantly higher than most western countries. The article also investigated the cost of higher education in England and found that it was among the highest in the world (Courtney 2019). Notably, the cost of education in the UK was found to be higher than the 25 countries that constitute the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Courtney 2019).

The US was the only country identified to have similarly high tuition fees. However, its public institutions of learning were identified to be significantly cheaper than similar institutions in the UK (Courtney 2019). Ironically, the same article by Courtney (2019) showed that the net return students get from studying in the UK is significantly lower than most OECD countries.

The cost-benefit analysis of pursuing higher education in the UK and China has been characterised by discussions that focus on the net income students get after graduation (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). Following this school of thought, several studies have shown that the societal benefits of acquiring educational degrees are far less than the cost paid to get them (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

The situation is worse in China because millions of students who graduate from universities do not get a job (Coates 2015). The situation is further catalysed by heavy investments made by families to pay tuition fees for their sons and daughters (Lai 2015). Therefore, it is not uncommon to find households which have spent a lot of money on educating their children and yet they stay home after graduation because of the lack of employment opportunities.

To address such concerns, the UK educational system has a robust financial support system for needy students. Furthermore, the government often makes significant investments in the education sector to make the fund more impactful and effective (Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). For example, it is reported that financial investments made in education are the fourth highest in the country (Courtney 2019). Stated differently, the UK has spent about four times its gross domestic product (GDP) on education (Courtney 2019). Therefore, the number of students who suffer from strained financial resources is lesser than China. Broadly, the high tuition fees associated with UK universities is commensurate with the demand for higher education in the country. Indeed, the UK is the second-most sought after destination for educational tourism in the world after the US (Courtney 2019).

Summary

A review of existing literature highlighted in this chapter has shown that several factors affect how educational tourism is practiced in China and the UK. Student attitudes, existing laws and educational costs have emerged as some of the most impactful forces influencing student behaviour in educational tourism. Although the findings mentioned in this chapter are elaborately developed and underpin different facets of educational tourism, the researcher observed that no studies have done a comparative analysis of educational tourism between the UK and China. This gap in research is filled by this study and the methods adopted in addressing the research issue are highlighted in the methodology section below.

Methodology

Introduction

This chapter highlights the methods used by the researcher to address the study topic. Key sections highlight the research approach, design, data collection methods, sample population and data analysis techniques used in the study.

Research Approach

According to Coe et al. (2017), there are two major research approaches used in academic research: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative method is often used to measure subjective variables, while the quantitative technique is for measuring quantifiable data (Uprichard & Dawney 2019). In this study, both techniques were integrated to form a larger mixed methods framework. The mixed methods approach was used in this study because of the complexity of the research topic (Moseholm & Fetters 2017).

This is because educational tourism is a broad concept that conceptualises different aspects of quantitative and qualitative investigations. For example, the legal basis for its implementation, which has been highlighted in the literature review above, is a qualitative issue because of its openness to interpretation. Similarly, the cost of education, which informs travel decisions and student experiences are quantitative concerns that had to be addressed in the study. Therefore, the mixed methods research approach provided a framework for integrating multiple sets of data. Its effectiveness in doing so is highlighted by Snelson (2016).

Research Design

According to Research Rundowns (2019), the mixed methods research framework is characterised by six research designs: sequential explanatory, sequential exploratory, sequential transformative, concurrent triangulation, concurrent nested and concurrent transformative methods. The major point of difference for the aforementioned designs is the order of prioritising the collection of qualitative and quantitative findings.

Based on the merits of each method, and as highlighted by Research Rundowns (2019), the sequential transformative method was used as the main research design. It does not prioritise the collection of either qualitative or quantitative data. Instead, either method of data collection could be adopted and the overall findings merged at the last stage of data analysis, which is the integration phase of research data (Research Rundowns 2019). This design gave room for the researcher to use a technique that best serves a theoretical perspective.

Data Collection Methods

The data collection process was implemented in two phases. The first one was meant to gather views regarding the impact of external factors on educational tourism in China and Britain, while the second one was meant to assess the role of intrinsic factors on educational tourism between the two countries. Data relating to the intrinsic factors affecting educational tourism were gathered using surveys and interviews, as the primary mode of data collection.

Alternatively external factors impacting educational tourism were reviewed by assessing secondary research data from reputable books, journals and websites. Collectively, these sources of information formed the triangulation technique of data collection, which was used to collect data, as described by Morgan (2019) and highlighted in figure 1 below.

According to Farrell, Tseloni and Tilley (2016), the triangulation method highlighted above is a robust way of collection data because one set of information could be compared with another and patterns identified for further analysis. For example, secondary research information was used to contextualise the primary data gathered from interviews and questionnaires. Similarly, the primary data obtained created the impetus for the collection of secondary data for verification purposes. Furthermore, secondary data provided guidance to the researcher to select relevant materials for review.

As will be explained in subsequent sections of this chapter, the triangulation strategy was also instrumental in safeguarding the validity of the research findings because of the integration of multiple aspects of data collection.

Stated differently, this method helped the researcher to cross validate the findings and identify patterns or areas of inconsistency that warranted further review. In line with this goal, the main motivation for using the triangulation method was to analyse the topic from different dimensions. Indeed, as proposed by Suharyanti, Masruroh and Bastian (2017), it was possible to increase the level of knowledge about the research phenomenon and to strengthen the foundation of the research findings by adopting the method because the triangulation technique supports a researcher’s views from various standpoints.

Sample Population

As highlighted in this chapter, data was gathered from two perspectives: primary and secondary information. Primary data involved the collection of qualitative information from the respondents using interviews and surveys. Since the interviews were lengthy, only four respondents were selected to participate in the research. Respondents who took part in the study comprised of Chinese and British students who have participated in educational tourism either in China or the UK. However, an exception was made to allow for the recruitment of participants who did not participate in educational tourism in any of the aforementioned two countries.

Similarly, those who studied in the two countries had an opportunity to participate in the study. The use of a small sample size in the research is justified through the works of Sekaran and Bougie (2016), which recommend that interviews should have less than 12 informants. The purpose of doing so is to improve the quality of engagement between the researcher and respondents.

The small sample of respondents selected to answer the research questions also aligns with the techniques used by other researchers to investigate a similar research topic. For example, Cockrill and Zhao’s (2017) interviewed only five respondents when seeking the views of Chinese students regarding their motivations to participate in education tourism in the UK. The small sample population selected for interviews also mirrors a similar approach taken by Sekaran and Bougie (2016) in conducting focus group discussions because the researchers undertook discussions that involved four respondents.

Therefore, instead of demanding that the informants state their views about the specific research issue in a structured manner (as would be the case in many quantitative assessments), the interview process allowed them to give their subjective opinions about the research topic in a relatively relaxed environment. To support this finding, Creswell (2014) says that interviews are an effective way of data collection because they benefit from the enrichment of data, which occurs when different people from diverse backgrounds discuss specific research issues. However, the main challenge associated with this data collection technique is the lack of a researcher’s control of the interview process (Creswell 2014).

Therefore, it is difficult to determine the quality or direction of research that will be generated from the study. Similarly, Creswell (2014) observes that some informants may be affected by “group thinking” when giving their views about the research topic, thereby creating the potential for variations to occur between the opinions they would give individually and as a group (Creswell 2014).

The stratified random sampling was selected as the main approach for recruiting respondents. In line with the principles of this sampling design, the researcher sorted the respondents’ views based on similar data features, such as gender, age and nationality. After executing this strategy, the researcher identified two sets of respondents (UK and Chinese students) who were later randomly sampled. This method was adopted because it reduced the possibility of bias during sampling because each group member had an equal chance of being selected, based on the demographic characteristic of each group (Creswell 2014).

For example, the UK students had an equal chance of being selected in the same manner as the Chinese students did. Lastly, for the quantitative aspect of the study, the researcher sought the views of 112 respondents to have a broad and representative understanding of the research issue. This approach is in line with the recommendations of Sekaran and Bougie (2016), which suggest that large sample sizes help to improve the reliability and effectiveness of research projects.

Primary Data

Primary data was collected using interviews and semi-structured questionnaires. According to Garner, Wagner and Kawulich (2016), there are two major types of questionnaires used to collect data in research: interviewer and respondent’s questionnaire. The interviewer questionnaire involves a direct way of collecting data using face-to-face interviews, whereby researchers ask direct questions and the respondents give similarly direct responses (Garner, Wagner & Kawulich 2016).

Comparatively, the respondent’s questionnaire is used in research investigations that highlight the role of informants as the main sources of data. This type of questionnaire often involves giving respondents an opportunity to answer questions without the direct involvement of the researcher in the data collection process (Creswell 2014). This method of data collection is often implemented online.

The researcher used semi-structured questionnaires to collect data and availed them to the respondents online (see appendix 1). Stated differently, information was collected from the respondents when the informants gave their views online. This method of data collection was selected for this study because it gave the informants adequate time to give their views because the researcher was not present when filing the form.

This data collection strategy was adopted because it was difficult to collect information physically as the respondents were dispersed across a large geographical area. The large sample of informants (n=112) selected to give their views about the research topic through quantitative questioning also informed the use of online questionnaires because it made the data collection process cost-effective. One of the main challenges associated with the collection of data using virtual means was the difficulty of responding to the questions posed by the informants on time. Therefore, it can only be assumed that the respondents understood the questions posed and answered them correctly. As will be highlighted in subsequent sections of this chapter, the member-check technique was used to address this challenge.

The questionnaire design for collecting primary research data was categorised into two sections. The first one was focused on collecting demographic data, which involved determining the respondents’ location, age, gender, income, nationality and education levels. The purpose of collecting this type of information was to understand key characteristics of the respondents and evaluate whether demographic differences influenced their views.

The second section of the questionnaire sought to find out the respondents’ experiences with educational tourism and whether they had participated in it in the first place. Key pieces of information that were sought in this area of assessment were the format of taking part in educational tourism, the length of time for participation and the number of students involved.

Important pieces of information that were obtained in this area of questioning related to the knowledge students expected to have obtained from participating in educational tourism, the identification of preferred destinations of travel and how long students intended to stay there. Other important data obtained in this line of questioning related to their satisfaction with the services provided through educational tourism and the affordability of the same services.

The last part of the data collection process was the interview stage and it was open-ended because it sought to find out the respondents’ subjective views regarding educational tourism (see appendix 2). These questions were open to the informants’ interpretation and appealed to the qualitative aspect of the data collection process. In this section of the questionnaire, the researchers were also required to state why they chose to participate in educational tourism.

The interviews were semi-structured because it enabled the researcher to have open discussions about the research topic formally. The small number of respondents (n=4) included in the study made it possible to have in-depth discussions with the research participants. According to Jenkinson et al. (2019), groups of less than ten people who want to discuss a topic or product launch are appropriate for interviews. The main justification for collecting data using interviews was its ability to measure students’ attitudes towards educational tourism. This line of questioning also helped to understand intrinsic motivations that shaped students’ field experiences (Lijadi & van Schalkwyk 2015).

One disadvantage associated with this technique is moderator bias because some observers note that researchers could influence the direction of the discussions by asking leading questions (Jenkinson et al. 2019; Lijadi and van Schalkwyk 2015). The researcher addressed this challenge by making sure the discussions were objectively oriented towards answering the research questions.

To guide the interview process, the researcher followed a guideline for asking the research questions but had the freedom to deviate from the main line of questioning if there was a need to do so. Therefore, not all the questions asked were framed before the interviews were conducted because some of them were simply created during the probing process. Thus, both the researcher and interviewees had the freedom to delve into the conversations in a more in-depth manner, as opposed to a rigid interview framework that leaves little room for off-the-cuff discussions. Relative to this technique, Creswell (2014) says that the interview method requires careful thought and planning.

The need to do so was recognised in this study when developing the research questions because the researcher carefully thought about the questions before undertaking the interviews and received supervisory approval before posing them to the respondents.

One of the major justifications for using the semi-structured interview method was its ability to allow for a two-way communication between the researcher and respondents (Creswell 2014). The use of the semi-structured interview process was also informed by a similar adoption of the technique by other researchers who have investigated related research issues. For example, Abubakar, Shneikat and Oday (2014) used the same technique to identify the main factors influencing educational tourism among a group of 31 respondents.

Secondary Data

As highlighted in this chapter, secondary data was sought as a complementary method of data collection. It was meant to contextualise the findings within the body of existing literature to find out whether they merged or diverged from the existing body of knowledge surrounding educational tourism in China and the UK. Emphasis was made to source credible and reliable published information by selecting articles, books or websites that were published within the last five years (2014-2019).

The justification for doing so was to receive updated information on the research topic. This need was informed by the importance of understanding the latest trends in educational tourism among British and Chinese students. Articles whose publication dates are older than five years may fail to capture such trends. Therefore, sources of secondary data were limited to a five-year publication time frame.

Additionally, the secondary data collected in this manner were mostly confined to educational materials contained in books, journal and credible websites. These three sources of data were selected for use in the investigation because they are credible and reliable (Creswell 2014). Indeed. As highlighted by Sekaran and Bougie (2016), the three sources of information have been extensively used in academic circles as credible sources of research information.

Data Analysis Methods

As mentioned in this chapter, three sets of data were generated from this study. The first one was qualitative information and it was generated from an interview process involving a select group of students who had participated in educational tourism within China and the UK. The second set of data (quantitative) was obtained using questionnaires that were filled online by a group of 112 students. The third set of data was obtained from secondary research. Its purpose was to offer a platform for comparing current findings with historical information about the research topic. Consequently, the researcher was able to identify areas of commonalities or divergence of opinions between the study’s findings and existing research. Each method of data collection had its own data analysis plan. They are discussed below.

Qualitative Data

To recap, qualitative data was obtained through interviews. Based on the subjective nature of the information collected, it was necessary to analyse this type of data using the thematic and coding method, which identifies patterns in responses and transforms them into key themes (Nowell et al. 2017). According to Nowell et al. (2017), the thematic and coding method has six key steps of data analysis, which include:

- familiarising the researcher with data,

- generating initial codes of analysis,

- searching for themes,

- reviewing themes,

- defining themes

- developing the final report.

The main justification for using the thematic method of data analysis in this study is its flexibility. Particularly, its ability to accommodate different types of theories gave room to the researcher to interpret the findings openly.

Quantitative Data

The Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and Microsoft Words 2013 were used as the main data analysis software for the quantitative data. The SPSS technique is a software package that has been used by several researchers to handle large volumes of data, while the Microsoft Word software also boasts of a similar merit (McCormick & Salcedo 2017). These competencies informed the use of the two techniques in this research process because there were 112 responses that had to be analysed. The SPSS method was also appropriate for this study because the researcher had the necessary technical skills of operating such a software.

This recommendation stems from the views of McCormick and Salcedo (2017), which suggest that SPSS users have to have the necessary skills needed to operate the software. Another justification for using the technique is its proven record in managing complex statistical data analysis procedures (Denis 2018). Its efficacy in this regard has been demonstrated by market researchers, data miners and other professionals who have employed it to undertake different types of statistical analyses (McCormick & Salcedo 2017).

However, the use of the SPSS software to analyse quantitative data was limited to descriptive analysis techniques, which helped to espouse the key characteristics of the data mined. Therefore, key features of the statistics that were generated from the data included (but were not limited to mean, frequencies and standard of deviation). These different characteristics of the data helped the researcher to make sense of the quantitative findings and ultimately link them to the research questions.

Secondary Data

As highlighted in this study, secondary data was one of the main sources of information in the study. It helped to contextualise the findings and identify areas of data convergence or divergence, relative to the findings of other researchers who have done similar investigations. Dozens of articles were analysed within this research framework using the thematic and coding method, as described in the qualitative section of data analysis above.

Ethical Considerations

The ethical considerations of a study refer to the duty to do what is right in the course of undertaking a research project (Creswell 2014). As with other types of research that involve human subjects, the need for conducting the investigation ethically was paramount. It was informed by the importance of protecting the rights of respondents when they gave out their views about the research topic (Creswell 2014).

In line with this practice, the researcher sought ethical approval from the university by completing the ethical form from university. Since the process of data collection was relatively straightforward and did not focus on collecting the views of organisations, there was no need to seek additional ethical approval from an external agency. As part of the institutional regulations governing research projects on international tourism and hospitality management, the researcher made sure that the ethical guidelines proposed in this study conformed to the Cardiff Met Research Governance Framework.

This model requires researchers to follow high standards of academic practice and honesty in the process of conducting educational research. Key principles underpinning this framework include honesty, responsibility, rigor and sustainability. Lastly, the researcher also complied with Cardiff Met requirements on confidentiality and anonymity by protecting the identities of the respondents when presenting the final report. This ethical practice was intended to allow the informants to speak freely without the fear of reprisals. This principle also prevented the researcher from disclosing any aspect of the research investigation without prior approval from the university or respondents.

Reliability and Validity of Findings

The reliability and validity of the findings presented in this study were safeguarded by the implementation of the member-check technique. This strategy allowed the researcher to share the study findings with the respondents to make sure that the information conveyed in the final report represented their original views (Management Association and Information Resources 2019).

The member-check technique has been supported by research institutions, such as the Management Association and Information Resources (2019), which have demonstrated its efficacy in improving the credibility, validity, reliability and transferability of research data. Its effectiveness in improving the quality of interview findings has also been highlighted by researchers, such as Burton (2017). Nonetheless, the ability to develop quality findings based on its merits depends on a researchers’ willingness to develop rapport with the respondents and obtain open and honest feedback.

Summary

As highlighted in this chapter, the mixed methods research approach was used as the overriding framework for this investigation. It gave room for the researcher to integrate qualitative and quantitative findings using the sequential transformative design. The quantitative investigation sampled the views of 112 students who had participated in educational tourism in China or Britain, while the qualitative findings were developed from interview discussions that involved four informants. Their findings were assessed using the SPSS method, Microsoft Word software and thematic techniques. Lastly, ethical approval was sought from the researcher’s university. Findings that emerged from the implementation of the above-mentioned techniques are highlighted in chapter 4 below.

Findings and Discussion

As highlighted in the methodology chapter above, the researcher collected views using three methods: interviews, questionnaires and secondary data. The data collection process was guided by the need to address four key research objectives, which were designed to investigate trends defining the participation of Chinese and British university students in educational tourism, investigate internal conditions affecting both sets of students, examine external factors influencing their behaviours and perceptions about educational tourism and discuss challenges associated with perception, policy, law, economy and other environmental aspects that characterise the Chinese and British higher education learning environments. The findings are highlighted below.

Questionnaire Findings

The questionnaire represented the main data collection instrument for gathering quantitative data. It was divided into two sections. The first one sought to collect the respondent’s personal data relating to their nationality, age, educational qualifications and gender. The first demographic data assessed within this framework was nationality. The findings are presented below.

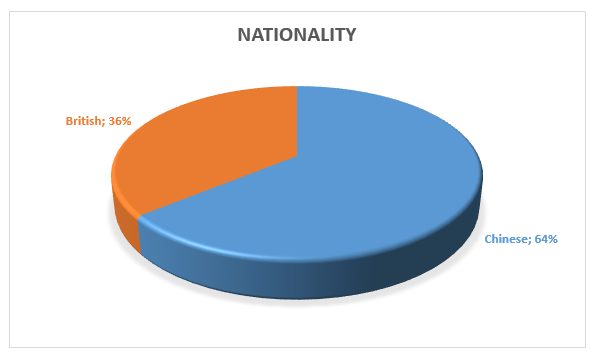

Nationality

Respondents who took part in the study had to be either British or Chinese students because the study sought to compare the educational experiences of students from both countries. According to the pie chart below, most of the respondents were Chinese (64%), while British students comprised 36% of the total sample. Figure 4.1 below outlines the findings.

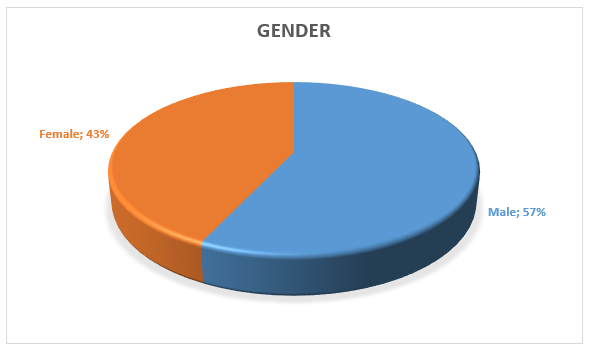

Gender

The respondents were also categorised according to gender as the second demographic variable examined in the study. According to figure 4.2 below, most of the respondents were male (57%), while 43% of them were female.

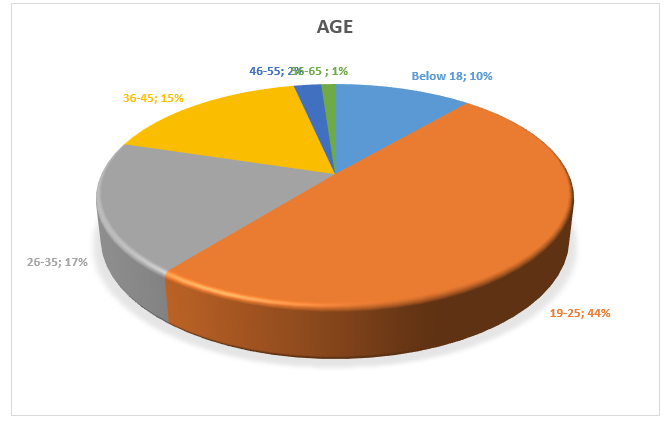

Age

The third demographic variable assessed by the researcher was the respondents’ ages. The informants had to input this variable in one of five key groups: below 18, 19-25, 26-35, 36-45, 46-55, 56-65 and above 65. Figure 4.3 below outlines the findings.

Educational Major

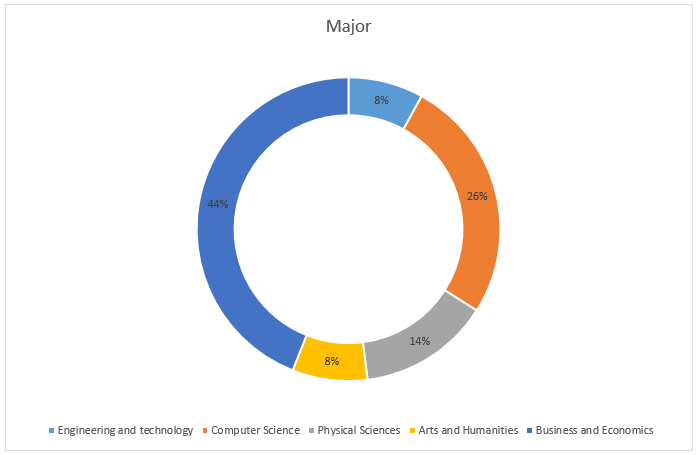

Another question posed to the respondents related to their educational major. They were required to select one area of specialisation among engineering and technology, computer science, physical sciences, arts and humanities and business and economics disciplines. Figure 4.4 below shows the response.

Experiences with Educational Tourism

Findings for Chinese Students (N=72)

In the second part of the questionnaire, the respondents were required to express their opinions regarding their experiences with educational tourism both in the UK and China. Focused on this area of discussion, the questionnaire helped the researcher to sample the experiences of the students regarding educational tourism based on different areas of assessment, including their awareness of associated programs, willingness to attend school field trips, personal experiences about school trips attended and organisation of the events. Table 4.1 below highlights the findings of these areas of investigation for the Chinese students who were 72 (n=72).

Table 4.1 Descriptive Statistics for Chinese Respondents (Source: Developed by Author).

Table 4.1 above shows the responses received from Chinese students regarding different aspects of their educational experiences. The columns titled “minimum” and “maximum” highlight the 5-point Likert scale used to assess their responses. Comparatively, the mean represents the general measure of responses adopted by most informants. The last column highlights the standard of deviation metric, which represents disparities in responses among the Chinese students who took part in the study.

The question with the highest standard of deviation related to “awareness of school field trips.” Most of the informants responded neutrally to this question, meaning that they “somewhat agreed” to being aware of their existence. However, the high standard of deviation associated with this area of assessment means that this question garnered the highest number of responses. Alternatively, it means that the informants seldom agreed on their views.

The second item posed to the respondents and highlighted on table 4.1 above related to how well the Chinese students wanted to participate in the school field trips. Most of them either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with this statement. For example, a mean score of 1.96 on the question regarding the theme of the school field trips means that most of the participants who participated in the field trips were pursuing a business-related course.

A score of 1.89 on the fourth variable under investigation (how many days was the school trip?) showed that most of the informants took part in trips that were either 1-3 days or 4-7 days long. In other words, most of the trips were short-term. When asked to state how much free time they had during the trip, the respondents’ views attracted a score of 2.39, meaning that most of them had between 1 and 2 free days.

The mean for the responses regarding the amount of money spent during the field trips was 3.71, meaning that most of the informants spent between £500- and £1,000 for their travel expenses. This amount of money included different areas of expenditure, such as transport, accommodation, food, tourist attractions and “others.” The mean for this variable was 1.39 meaning that the “other” category accounted for most of the expenditure highlighted above. In other words, the amount of money spent on the trips was not only limited to the key areas of expenditure mentioned above.

Most of the respondents who took part in the study and attended their school trips came from multiple universities. This finding is determined by the mean of 2.07, which was attributed to this area of questioning. The next area of investigation (when did the informant attend the school trip?) had a mean of 1.05, meaning that most of the students were in their fourth year of undergraduate. The next area of assessment involved a multiple choice questioning platform where the respondents were asked about their personal experiences about the school trip. The educational significance, organisation of school trip, outcomes, food, accommodation and transport were some of the issues reviewed in the assessment.

Relative to this area of questioning, most of the respondents said they were satisfied with the school field experiences because the mean for their response was 2.18. The last area of assessment for the Chinese students involved an assessment of their views regarding their willingness to participate in future educational tourism activities. The overall mean for this area of questioning was 2.07, which implies that most of the informants were willing to participate in such activities in the future.

Findings for UK Students (N=40)

Similar to their Chinese counterparts, the UK students also gave their views about different areas of educational tourism, including their awareness of associated programs, willingness to attend school field trips, personal experiences about the school trips attended and the organisation level of the events. Table 4.2 below highlights the findings of 40 (n=40) UK students who participated in the study.

Table 4.2 Descriptive Statistics for UK Students (Source: Developed by Author).

The statistics presented above are interpreted in the same manner as those of the Chinese students. Consequently, the columns titled “minimum” and “maximum” highlight the 5-point Likert scale used to assess their responses, while the “mean” represents the general measure of responses adopted by most informants regarding different areas of questioning. The last column highlights the standard of deviation, which represents disparities in responses among the students who took part in the study. The question with the highest standard of deviation had multiple choices and it related to the respondents’ experiences with the school trip.

In a cluster format, the responses given by the informants on this area of assessment related to their personal experiences with the school trips, their educational significance, organisation of events, outcomes, food, accommodation, transport and sight-seeing. The question with the least standard of deviation related to the activities included in the fee paid. This finding means that there was a standardised expenditure for most of the school trips attended by the UK respondents.

When asked to state whether they were aware of the existing school trip programs at their various institutions of higher learning, most of the informants responded neutrally meaning that they “somewhat agreed” to being aware of the school field trips. However, the high standard of deviation associated with this area of questioning means that this part of the assessment garnered a high number of varied responses. The variation is an indicator that the informants seldom agreed on their educational experience. The second item investigated in this line of questioning related to how well the respondents wanted to participate in the school field trips.

Most of them either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with this statement because the mean score for this question was 1.95. Alternatively, a mean score of 2.35 on the question regarding the theme of the school field trips meant that most of the informants who participated in the field trips were pursuing a language-related course.

A score of 1.30 on the fourth variable under investigation (how many days was the school trip?) showed that most of the informants who took part in the school trips only spent less than 7 days on their travels. In other words, most of the trips were short-term. When asked to state how much free time they had during the trip, the respondents’ scored 2.73, meaning that most of them had between 1 and 2 free days.

The mean for the responses regarding the amount of money spent during the field trips was 3.68, which implies that most of the respondents spent between £500 and £1,000 for their travels. This amount of money included different areas of expenditure, such as transport, accommodation, food, tourist attractions and “others.” Alternatively, when the respondents were asked to state which area of expenditure was mostly covered by the fee paid, most of them said that the cost was attributed to “other” areas of expenditure. The mean for this variable was 1.23, meaning that the “other” category accounted for most of the expenditure.

Stated differently, the amount of money spent on the trips was not only limited to the key areas of expenditure highlighted above but also additional areas of expenditure that were not covered in the questionnaire.

Most of the respondents who took part in the study and attended their school trips came from UK universities. This finding is determined by the mean of 1.88, which was attributed to this area of questioning. The next area of assessment (year when attended the school trip) had a mean of 1.05, meaning that most of the students were in their post graduate program or in their fourth year of undergraduate education. The line of questioning with the highest standard of deviation involved the multiple choice table where the respondents were asked about their personal experiences about the school trip (see appendix 1).

The educational significance, organisation of school trip, outcomes, food, accommodation, and transport were some of the issues reviewed in the assessment. Relative to this area of questioning, most of the respondents said they were satisfied with their school field experiences because the mean for their response was 1.95. This score meant that most of the respondents either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that they had a positive experience from the school trips. The last area of assessment involved a review of the respondents’ views regarding their willingness to participate in future educational tourism activities. The overall mean for this area of questioning was 1.47, meaning that most of the informants were willing to participate in such activities in the future.

Interview Findings

The second part of the data collection process involved the collection of interview findings. This stage of the data collection process helped to generate qualitative data that was used to make sense of the quantitative findings. Indeed, it was meant to gather subjective views of the respondents’ views regarding different aspects of educational tourism. A semi-structured interview was used as the main data collection instrument. It contained four key areas of information assessment: background information, discussion about education and field activities, an investigation of personal experience of the field trips between the UK and China and the importance of the field trips to the informants.

The interview process was undertaken in two sets. The first one contained an investigation of the views of respondents who participated in UK field trips and the second one was for those who took part in Chinese field trips. The findings of each stage of the interview process are discussed below.

Chinese Respondents

Background Data

The first section of the interview related to the respondents’ educational background. Students gave details about the name of their universities, grade, course and topic of the field trip. Two of the respondents who took part in the study came from Chinese-based universities located in Shanghai and Beijing. They were both pursuing an undergraduate course in business. One of them was in the first year of study, while the second one was in her second year of study. Both respondents had participated in a field trip to the UK, but on different occasions and date. A review of their opinions regarding their educational experiences is highlighted below.

Discussions about Activity

As highlighted above, the first two sets of respondents interviewed in this study participated in a field trip to the UK. The first one said that their travel experience involved 24 students who went to Britain for a recreational and educational field trip. The informant was a basketball player who participated in the field trip as a technical member of the school team. The respondent also remarked that they engaged in a lot of social activities, ranging from clubbing, partying, sight-seeing and visiting historical sights. He also said that most of the activities that occurred in the field trip involved reflection and observations studies.

Personal Experience of Field Trip

The respondents were also required to describe their personal experiences about the school field trips. The Chinese respondents said that they generally enjoyed visiting the UK. In fact, one of them disclosed that the trip was the first opportunity he had of travelling outside China. The tour was organised and paid for by their institution (school). The researcher also asked them about the possibility of Chinese students organising such field trips and both of them answered affirmatively by saying that it was difficult for Chinese students to embark on such trips because of resource limitations. One of them claimed that the lack of proper international exposure was a significant barrier to the organisation of successful school field trips. Relative to this assertion, he said,

“I think there is a big difference between how Chinese universities and western universities organise for field trips because I think the Chinese society has been isolated from the rest of the world, in terms of culture and language, to the extent that many western universities have institutionalised their international educational programs at the expense of non-English-speaking countries. You could only deduce from the decades of experience that western universities have had with admitting international students and mirror the same to the Chinese universities…..they cannot compete.”

When asked to describe their good and bad experiences when participating in the school field trips, the Chinese interviewees claimed that language barrier was a significant impediment to their interactions with host communities. To support this assertion, one of the respondents said,

“I found that there is a huge cultural divide between the UK and China. I mean…everything, from the way we talk, relate and even organise our educational programs is different. Therefore, it is quite a challenge developing close relationships with other students because we do not share the same culture.”

The other respondent gave a more positive account of the field trip experience by saying that he was excited to interact with new people, albeit strained. Particularly, he mentioned how visiting the UK gave him a broad view of life, because he was able to understand his culture better by comparing his native experiences about education and life in general with how UK students lived. He went ahead to give an example of how a discussion with a UK colleague made him understand the educational expectations of Chinese and UK students.

Relative to this discussion, he found that Chinese students had different expectations of their educational goals from their UK counterparts because the latter was more concerned with acquiring educational skills for the advancement of their careers and lives, while the Chinese studied to get a well-paying job and eventually affording a good life. The informant attributed his understanding of these cultural differences to the exposure he received from attending the school trips.

Importance of Field Trips

When asked to state whether the field trips were important to their educational progress, all the informants responded affirmatively. Particularly, the students said that the field trips were essential in helping them bridge theoretical knowledge with hands-on experience. One of the respondents said that after travelling, he finally understood why field trips were an important aspect of their educational curricula. He disclosed that this was not the case for all universities in China because some of them graduated their students without necessarily organising for a field trip. When asked to state whether she thought of herself as a learner or traveller during the field experience, she said that she believed she was a learner. The other respondent thought of himself as being both a learner and traveller. To back up his claims, he said,

“You know, I have always thought of myself as an explorer of some sort and learning is only a by-product of it. Therefore, whenever, I engage in any school field trip, I first think to myself… how will it contribute to my sense of adventure and secondly, what can I learn from it?”

The respondents also said that the field trips were instrumental to their educational progress because they gave them the exposure they needed to advance their careers and personal lives. They deemed it necessary to take part in such events because they could acquire a lot of knowledge that they would not ideally have if they were confined to their classroom or home environments. Relative to this discussion, one of the respondents said that field trips were edged in his memory. He believed he could not forget any experience he had, but the same could not be said for the acquisition of learning materials because he struggled to understand the educational content taught in class. Therefore, he considered the field experience as an “eye-opener.”

The second respondent had a contrary view because he always thought of himself as a learner and not a traveller. He argued that travelling was not a hobby because he did not like to take flights and often became sea sick whenever he took voyages. Therefore, his participation in the school field trips was more of an obligation to fulfil his educational requirements and not necessarily a platform to advance his personal goals. Therefore, he thought of himself as a learner and not a traveller.

UK Respondents

Background Data

As was the case with the Chinese respondents, the first section of the interview process related to the respondents’ educational background. They gave details about the name of their universities, grade, course and topic of the field trip. There were two respondents who took part in the study and both of them came from UK-based universities located in Liverpool. They were both pursuing an undergraduate course in language and arts. One of them was in the first year of study, while the second one was in her third year of study. Both respondents had participated in a field trip to China (Shanghai). A review of their opinions regarding their educational experiences and activities is highlighted below.

Discussions about Activities

As highlighted in this paper, two of the respondents interviewed were UK students who had participated in an educational trip to China. Both of them were in their second year of undergraduate program, pursuing courses in language and arts. Their field trip topics were also confined to the same areas of study. Unlike their Chinese counterparts, the UK respondents said that their field trips involved less than 10 people. One of the respondents even said that their group only had five students who travelled to China on an educational exchange program. Most of the activities that were organised during the field trips involved sight-seeing and visiting historical sights, like the Great Wall of China.