Introduction

Background of the Study

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as modern businesses and new ventures are actively discussed as contributing to the economic growth in both the developed and developing countries because of their focus on the modern marketing tools (Arend 2014; Lahtinen 2013; Lawrence et al. 2006; Sharma 2011). In this context, the SMEs are considered as actively oriented to using the tools of such a modern approach to marketing as entrepreneurial marketing. According to Morris and the group of researchers, entrepreneurial marketing is focused on exploitation of opportunities and innovative approaches to attract customers and increase profitability (Morris, Schindehutte & LaForge 2002). However, it is important to discuss the role of entrepreneurial marketing for modern SMEs with references to their sustainability because the process of achieving sustainability and addressing the economic, social, and environmental issues is the main task for all businesses, regardless their size and scope of activities (Morrish 2011; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). In this context, the sustainability concept dictates that an entrepreneurship activity should have the capacity of meeting the present needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own need (Masurel 2007; Starik & Kanashiro 2013).

Sustainable entrepreneurship is based on establishing a balance between the planet, profit, and people. Therefore, focusing on achieving sustainability, the SMEs become engaged in the environmental activities that help a business to utilize market opportunities with an objective of improving profitability; become concentrated on creating the value for the society; and become oriented to implementing effective strategies to increase profits (Lawrence et al. 2006; Parrish 2010; Tambunan 2008). However, the problem is in the fact that it is more difficult for the SMEs to achieve sustainability than for large companies because they often fail to include environmental and social considerations in their plans and activities, thus threatening their sustainability (Loucks, Martens & Cho 2010; Simpson, Taylor & Barker 2004). In this context, it is necessary for the SMEs to consider the issue of sustainability while choosing marketing techniques, methods, and tools.

SMEs play a major role in economic development and ensuring sustainability as they have been the central source of employment generation and output growth (Kongolo 2010; Simpson et al. 2004; Tambunan 2008). In both developed and developing countries, SMEs employ higher percentage of citizens as compared to large corporations and government agencies. They represent the highest percentage of all enterprises (Stefanović et al. 2010; OECD 2009). For example, in developed countries, SMEs represent over 99 % of all enterprises in the European Union, and 99.3% in the United Kingdom business sphere (Mark Ware Consulting Ltd 2009; OECD 2009). In addition, SMEs in developing countries also witness a high parentage in total business. For example, in Saudi Arabia, the majority of businesses are SMEs, representing 92% of all business in the country (Alsaleh 2012; OECD 2009). However, in view of failed environmental responsibility, 60% of carbon dioxide emissions in the UK are from the SMEs and this is a threat to their growth and development (Alsaleh 2012; Simpson et al. 2004).

Saudi Arabia is one of the fastest developing economies in the Middle East, and it is regarded as one of the biggest economies in the Gulf Cooperation Council (OECD 2009; Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency 2010). The country has numerous SMEs that have helped it to experience a relatively stable economic growth. However, there is limited scientific evidence on the position of SMEs in Saudi Arabia. According to Alsaleh, about 92% of all registered business units in Saudi are SMEs and 80% of the country’s workforce is from these SMEs. However, their contribution to the GDP is only around 33% (Alsaleh 2012; Riyadh Camber Commerce & Industry 2011). The importance of SMEs has raised a massive attention among researchers and other stakeholders on how these firms can become successful. Gladwin argued that although the SMEs are very important for a country’s economic growth, most of them always fail soon after starting operations, an issue of sustainability (Gladwin 2010). In Saudi Arabia, it is estimated that the average life span of SMEs is seven years. It means that most of these firms fail to celebrate their seventh anniversary (Allurentis Limited 2013; Alsaleh 2012; Ahrholdt 2011; Ramachandran et al. 2006). Another major concern is that although the SMEs account for about 92% of all the registered firms in Saudi, their contribution to the country’s GDP has consistently remained below 33% (Nasr & Rostom 2013; Sadi & Iftikhar 2011). Maser (2012) argued that this is critical, especially given the fact that this sector employs about 80% of the country’s population. In contrast with developed countries such as the United States and United Kingdom, where SME is one of the leading contributors to the GDP (Gilmore, Carson, & Grant 2001; Hall, Daneke, & Lenox, 2010). This issue has attracted attention of many scholars who have been concerned on how to enhance SMEs’ sustainability and efficient in their operations.

Generally, the SMEs face many challenges that inhibit their sustainability and survival such as lack of future planning, absence of innovation, managerial skills, financial support, marketing knowledge and competencies or human resources capabilities (Alsaleh 2012; Dyer & Ross 2008). In literature, it is postulated that entrepreneurial marketing is a potential driver and predictor of SMEs’ sustainability, and its tools are effective to address challenges associated with SMEs’ sustainability. Thus, researchers have demonstrated the relationships between the dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing and business sustainability (Franco et al. 2014; Hacioglu et al. 2012). From this point, more researches are needed in order to further examine and confirm the positive effect of entrepreneurial marketing on SMEs’ performance and sustainability (Hall et al. 2010; Morris et al. 2002).

With regards to this study context, the Saudi government and the private sector initiatives to provide the support for Saudi SMEs in terms of capital (debt and equity) were recently in place. Under the supervision of the Ministry of Finance, the Saudi Industrial Development Fund (SIDF) has established a special program called “kafala” fund which provides financial facilities for Saudi SMEs (Alsaleh 2012; Aragon-Correa et al. 2008). The Saudi Credit Bank has also distributed social loans to low income Saudis, helping them to start their own businesses (Hertorg 2010; Sivakumar & Sarkar 2012). These efforts by the government are meant to foster the expansion of SMEs (Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency 2010; Sivakumar & Sarkar 2012). The private sector also plays a considerable role in supporting SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Hertog (2010) indicates the essence of support programmes executed by private agencies that help SMEs in the Gulf region gain external resources through learning and sharing (Hertorg 2010; Sivakumar & Sarkar 2012).

Despite the fact the government has outlined policies to support the Saudi SMEs, this move is still considered shallow and ineffective (Saudi-US Relation Information Service 2011; Shalaby 2004). Masurel advocates for policies that enable SMEs to control their level of production by regulating external networks, for example, suppliers, customers and local authorities (Masurel 2007). Moreover, most of the supporting programs focus on financial support while ignoring the other sustainable factors such as environmental and social programs (Alsaleh 2012; Saudi-US Relation Information Service 2011; Shalaby 2010). This research focuses on SMEs sustainability that can be practiced in SMEs in Saudi Arabia through entrepreneurial marketing dimensions. Specifically, this research intends to investigate the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing dimensions and SMEs business sustainability with relation to Saudi SMEs.

Problem Statement

The progress of SMEs in developing countries depends on the organizations’ approaches to sustainability and success. Thus, the success of SMEs is defined as the ability of a SME to endure the first two critical years after startup (Moore & Manring 2009; Müller & Pfleger 2014). In this context, Kesper states that developing countries have unpredictable market conditions, and there is little chance for the SMEs to become successful (Kesper 2001). In addition, the owner should meet the majority of goals and objectives, and managers in many SMEs are under the increasing pressure to address the issue of sustainability (Asif et al. 2011; Moore & Manring 2009). From this point, the achievement of sustainability for the SMEs in developing countries becomes a problematic task, and it is associated with the concept of competitive advantage. The resource-based view discussed in literature indicates that resources, core competencies and capabilities are imperative in defining a firms’ competitive advantage (Müller & Pfleger 2014; Sull & Escobari 2004). This competitive advantage is vital in ensuring the SME’s sustainability. The strong support for SMEs in the Asian developing countries, including countries such as Saudi Arabia, is necessary to develop sustainability and achieve the competitive advantage (Loucks et al. 2010; OECD 2009). Therefore, researchers should examine the SME’s sustainability in developing countries in order to determine tools to achieve the competitive advantage.

From this point, strategic resources are fundamental to gain the competitive advantage and to guarantee the SME’s sustainability. Thus, these resources are necessary to achieve the better firm performance in comparison to competitors because these resources help the firms deal with their constraints; thereby, realizing the development and strategic growth (Amoah-Manseh 2013; Sull & Escobari 2004). In this context, the competitive advantage is gained through the possession of unique firm resources that are often absent in Saudi Arabian firms (Alsaleh 2012; Nasr & Rostom 2013; Sadi & Iftikhar 2011). The ability of a firm to appropriately manage resources determines its performance level and attainment of competitive advantage. However, without the right personnel, management of resources becomes difficult and SME sustainability is not guaranteed. From this perspective, the SMEs in Saudi Arabia need to find specific resources and tool to promote their sustainability.

The problem is in the fact that the key concern for the SMEs in Saudi Arabia is the sustainability issue (Alsaleh 2012; Hertorg 2010; Sivakumar & Sarkar 2012). The SMEs in Saudi Arabia, on average, last only about seven years because of the inability to achieve sustainability in perspective (Alsaleh 2012; Hertorg 2010). A range of problems have been cited as the drawbacks making the SMEs unable to compete effectively and grow sustainably (Nasr & Rostom 2013; Sadi & Iftikhar 2011). The challenges facing SMEs in general are funding, high cost of capital, restriction of financial application, lack of managerial and marketing capabilities (Al-Jasser 2011; Alsaleh 2012; Alsamari et al. 2013; Hertorg 2010; Rocha et al. 2011, Shalaby 2004, 2010). The identified challenges can be addressed while developing the approaches to achieve sustainability in SMEs because of the aspects of sustainable entrepreneurship.

For illustration, it was found in Alsamari et al. study on the SMEs’ challenges and opportunities in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain that poor implementation of the marketing process was a precedent factor for failure of the enterprises (Al-Jasser 2011; Alsamari et al. 2013; Berghman et al. 2013; Saudi-US Relation Information Service 2011). The other studies also confirm that marketing is one of the main problems in SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Thus, in an investigation conducted by the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Council (SMEDEC) on 60 SMEs in Eastern province of Saudi Arabia, it was shown that over 78% of these SMEs had problems of marketing (Alsamari et al. 2013; Shalaby 2010). From this point, it is necessary to focus on dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing as important to influence sustainability of SMEs in Saudi Arabia.

In literature, it has been discussed that entrepreneurial marketing is very much needed in SMEs’ context due to the challenges and financial constraints encountered (Kurgun et al. 2011; Müller & Pfleger 2014). Entrepreneurial marketing as based on a specific entrepreneurial behavior is an effective approach to revise the vision of a range of constraints and to focus on the ways that are appropriate to gain benefits and attract stakeholders (Gaweł 2012; Kurgun et al. 2011). Thus, entrepreneurial marketing is associated with innovation and innovative techniques and strategies that are discussed as effective to address the needs of modern and developing SMEs that find new approaches to building their competitive strategies (Gaweł 2012; Kurgun et al. 2011).

Researchers state that entrepreneurial marketing dimensions such as proactiveness, innovativeness and resources leveraging are associated with enhancing business sustainability in companies (Hacioglu et al. 2012; Kurgun et al. 2011). In this context, researchers pay attention to the role of the businessman’s active behavior while selecting opportunities in order to develop organizations; to the specific role of choosing innovative techniques to use for adding to the competitive advantage; and to the role of resources leveraging for the effective planning and utilization of the available resources and business opportunities (Gaweł 2012; Kickul & Gundry 2002; Morris et al. 2002). Thus, more researches are necessary to state whether aspects of entrepreneurial marketing can contribute to creating sustainability in different companies, including SMEs.

In addition, the isolated studies have shown that value creation and customer intensity might relate to proactiveness, innovativeness, and resource leveraging (Hacioglu et al. 2012; Kurgun et al. 2011). As a result, it is possible to speak about the inter-relationships between the dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing (Gaweł 2012; Hills & Hultman 2011). However, there is a lack of studies presenting the evidence to support this idea. In this context, it is important to research separately the effects of value creation and customer intensity might on proactiveness, innovativeness, and resource leveraging in the context of the SMEs’ progress and their sustainability.

The problems are also in the fact that there is much theoretical information on the topic that is not supported with empirical researches and case studies. The existing studies are rather fragmented, and they are focused on sustainability, the progress of SMEs, and on the elements of entrepreneurial marketing and their role for the firm performance (Hacioglu et al. 2012; Hills & Hultman 2011). Nevertheless, there is still the lack of an integrated study to examine the effect of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions on small and medium enterprises’ business sustainability (Collinson & Shaw, 2001; Hacioglu et al. 2012). The research is necessary to explore the problem in Saudi Arabia where SMEs actively develop in spite of a range of challenges. Furthermore, it is also important to examine how the dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing relate to each other.

Research Questions and Objectives

The general research question of this research is whether entrepreneurial marketing dimensions have significant effect on SMEs’ business sustainability, and what are the likely inter-relationships between the dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing. This research aims to answer the following specific research questions:

- To what extent proactiveness, innovativeness and resource leveraging (i.e. dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing) affect SMEs’ business sustainability?

- To what extent value creation and customer intensity have effects on SMEs’ proactiveness?

- To what extent value creation and customer intensity have effects on SMEs’ innovativeness?

- To what extent value creation and customer intensity have effects on SMEs’ resource leveraging?

The general objective of this research is to examine the effect of entrepreneurial marketing on SMEs’ business sustainability and to examine the inter-relationships between the dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing.

Specifically, this research aimed at achieving following objectives:

- To examine to the predictive effect of proactiveness, innovativeness and resource leveraging on SMEs’ business sustainability.

- To examine the predictive effect of value creation and customer intensity on SMEs’ proactiveness.

- To examine the predictive effect of value creation and customer intensity on SMEs’ innovativeness.

- To examine the predictive effect of value creation and customer intensity on SMEs’ resource leveraging.

Scope of the Research

The scope of research focuses on the investigation of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions in achieving SMEs sustainability in the context of Saudi Arabia. Legally registered SMEs will be selected. SMEs have been targeted because of their highly competitive nature and their large contribution to GDP. Business entrepreneurs and owners of SMEs will be interviewed using structured questionnaires that will be administered personally by the researcher. The present study adopts the definition presented by Shalaby of SMEs in the Saudi context which states that SMEs as companies that are employing less than 100 employees (Shalaby 2004).

Contribution of the Study

This study is expected to contribute to the theory and management practice. In terms of theoretical contribution this research will focus on determining the relationship that exists between entrepreneurial marketing and SMEs sustainability. This study will add to the existing knowledge of entrepreneurial marketing and sustainable development studies by examining the relationship between value creation, customer intensity, proactiveness, innovativeness, resource leveraging and SMEs business sustainability. In comparison to other studies, this study will test the relationship between value creation and resource leveraging, customer intensity and proactiveness, and value creation and resource leveraging for the very first time.

Furthermore, this study will examine, particularly, the specific key dimensions that affect sustainability of SMEs. In addition, the study will also provide empirical evidence on the entrepreneurial marketing by validating a model of sustainability in SMEs. This study also provides support for addressing the call by Morris et al. (2002) about having more insight about the inter-relationships between the entrepreneurial marketing dimensions which will contribute significantly to the existing knowledge.

In the aspect of management practice, most of the current business units in Saudi Arabia have failed to achieve sustainability in their operations because of lack of sufficient knowledge of the best practices in their field. The term sustainability is relatively new especially among Saudi SMEs. This study will provide useful practical information with relation to entrepreneurial marketing dimensions and its effect on SME business sustainability. The information is valuable in order for SMEs to structure their limited resources in the areas that directly influence their business sustainability. The results of this study would indicate which entrepreneurial marketing dimensions would potentially explain the variance in business sustainability and the likely predictive effect of value creation and customer intensity on SME proactiveness, innovativeness and resource leveraging thus enable SME to fully maximize their limited resources. The findings also serve as reference for small and medium sized entrepreneurs and managers in other countries with similar socio-economic and political structure as Saudi Arabia.

This research study also seeks to provide knowledge to the entrepreneurs and other business executives managing SMEs on how entrepreneurial marketing can help them achieve sustainable advantage in their operations. This research will also give advice to business executives of SMEs on the importance of hiring skilled employees who understand marketing dynamics and able to define the best ways of achieving sustainability. SMEs will also gain further understanding on how to apply entrepreneurial marketing as an antecedent for gaining sustainable advantage.

Operational Definitions of Key Variables

Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) business sustainability refers to the “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (qtd. in Müller & Pfleger 2014, p. 317). The concepts of sustainability and sustainable development describe “the social goal of improving and maintaining human well being over a long-term time horizon within the critical limits of life-sustaining ecosystems” (Parrish 2010, p. 512).

Proactiveness refers to the anticipation of future demands of firms related to market opportunities and environment (Morris et al. 2002).

Innovativeness refers to the mechanism of searching for creative, unique, and new products, services, solutions, technologies and processes (Morris et al. 2002).

Resources Leveraging refers to the means for unrecognized resources that not has been used in the past while considering making the optimal use of the current limited resources (Morris et al. 2002).

Value creation refers to the ability to find and combine different and unique resources that are undiscovered, in order to produce value for customers (Morris et al. 2002).

Customer Intensity refers to ways of customer acquisition, retentions and development that explains an entrepreneur’s efforts to provide a certain level of customer investment and customization (Morris et al. 2002).

Structure of Proposal

This proposal consists of four chapters. Chapter I is introductory. The chapter presents the background of the study, the problem statement discussing the importance of the study, research questions and objectives of the study; it discusses the scope of the research and its contribution to the field; and it provides the operational definitions applied to the study. Chapter II presents the literature review on the main aspects of the topic. The chapter discusses the sustainability theories, the sustainability concept, the SMEs’ sustainability, entrepreneurial marketing and its dimensions. The chapter also analyses the research gap in the recent studies on the problem to support the need for the current study. Chapter III presents the conceptual framework for the research and hypotheses aligned with research questions. Chapter IV provides the methodology used for the research with the focus on explaining the sampling, data collection, and data collection procedures. The proposal also includes the research schedule.

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter illustrates the theories related to the organisation performance and sustainability concept. Then, it focuses on explaining Small and Medium Enterprises’ (SMEs) sustainability and its predictors in the form of entrepreneurial marketing. It is followed by the discussion of SMEs in Saudi Arabia context and the research gaps with reference to the existing literature.

Institutional and Contingency Theories

Institutional Theory

The concepts of organisation performance and sustainability can be explained with references to Institutional Theory and Contingency Theory. Institutional Theory offers insights and explanations regarding the reasons why entrepreneurs choose certain practices without focusing on direct economic revenues and profits (Brunton & Ahlstrom, 2010; Webb et al. 2011). According to the theory, determinants of investment in corporate sustainability strategies are influential, but much attention is paid to the role of regulations, certain laws, and activities of governmental agencies in determining the practices followed by entrepreneurs (Brunton & Ahlstrom, 2010; Rivera 2004; Webb et al. 2011). From this point, sustainability becomes the results of implementing a range of societal and environmental practices influenced by such factors as the social environment, tradition, culture, and regulation. In this context, economic incentives are less important than the focus on societal and environmental practices in order to achieve sustainability.

Institutional Theory explains how entrepreneurs can improve their positions in the business world while focusing on the aspects of regulation and legitimacy; thus, the theory explains how it is possible to operate within the legal environment and benefit from it (Delmas & Toffel 2004; Glover et al. 2014). According to the concepts of the theory, social and legal institutions serve as a set of working rules, and these rules provide a framework for the effective decision-making (Delmas & Toffel 2004; Lai, Wong & Cheng 2006). Thus, the main premise of Institutional Theory is that to survive, firms must focus on the idea of legitimacy by conforming to prevailing institutional pressures and rules in the legal and societal environment.

Institutional Theory provides the grounds for organisations within different industries in relation to the choice of the effective practice in order to stay profitable in the changing environments. Thus, Institutional Theory states that it is necessary to seek legitimacy by conforming to prevailing institutional rules in order to address the issues associated with the sustainable progress (Bansal & Clelland 2004; Starik & Kanashiro 2013). In this context, Institutional Theory is helpful to create the framework for discussing the role of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions for sustainability of the SMEs because it is effective to explain how changes in social environments and values as well as changes in the social and environmental regulations can influence the sustainable practices of businesses (Delmas 2002; Glover et al. 2014; Wu, Ding & Chen 2012).

Contingency Theory

Contingency Theory has been widely referred and used in studies on measuring the performance and effectiveness of an organisation due to the fact that the theory focuses on determining and measuring a range of contingencies that are influential for building sustainability. These contingencies include the size of a business, uncertainty of the environment along with environmental issues, the development of technology, and risks (Buttermann, Germaina & Iyer 2008; Ketokivi 2006). Following Contingency Theory, it is possible to state that these indicators affect significantly the progress of the business and the success of entrepreneurs’ activities. The impossibility to influence the contingencies associated with the aspects of the social, economic, and environmental areas affects negatively businesses’ abilities to achieve sustainability (Ketokivi 2006; Stonebraker & Afifi 2004). According to Contingency Theory, there is no optimum method to develop or systematise a strategy for a firm and propose the framework for the organisation (Buttermann et al. 2008; Stonebraker & Afifi 2004). As a result, entrepreneurship becomes dependent on contingencies, and a company cannot regulate its activities to meet the changes in the progress of the social, economic, and environmental areas (Canina et al. 2012; Raduan et al. 2009; Starik & Kanashiro 2013). In this context, it is possible to state that Contingency Theory argues that the most appropriate structure for an organisation is that one that can best fit a given operating contingency, such as technology or the environment.

Contingency Theory is expected to help the SMEs’ business entrepreneurs to adopt the structural innovations in the daily operations of their business because this theory can explain what factors influence the success of entrepreneurs’ efforts in realising the principles of the sustainable development for businesses of different sizes. Therefore, Contingency Theory provides the important framework in order to discuss the idea or hypothesis that contingencies presented in the context of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions can affect sustainability of the SMEs (Canina et al. 2012; Raduan et al. 2009; Stonebraker & Afifi 2004). While discussing the focus on contingencies as the focus on tools that are effective to achieve sustainability in SMEs, it is possible to state that Contingency Theory is an appropriate choice to explain why dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing can contribute to creating sustainability and support specific sustainable practices in the SMEs (Raduan et al. 2009; Stonebraker & Afifi 2004).

In summary, Institutional and Contingency Theories postulated that an organisation performance and sustainability are affected by a range of factors, including the changes in the legal environments and regulation, as it is according to Institutional Theory and including influential contingencies, as it is according to Contingency Theory. As a result, both theories postulated that the success of businesses in achieving sustainability can be predicted with references to the organisations’ strategies and their specific responses to factors, such as social and environmental pressures (Glover et al. 2014; Raduan et al. 2009; Stonebraker & Afifi 2004). From this perspective, while assuming that entrepreneurial marketing is the part of organisational strategies, it is likely to state that implementation of proactiveness, innovativeness and resource leveraging would have an effect on organisations’ performance and sustainability. Therefore, the aspect of sustainability should be discussed in more detail than the role of the identified factors for the organisational performance. The following sub-sections in this chapter would illustrate the concept of sustainability in detail.

Sustainability Concept

Sustainability can be viewed from various dimensions, but environmental and social dimensions have received the immense emphasis (Brilius 2010; Moore & Manring 2009). Based on the environmental approach, sustainability is achieved by SMEs using informal methods that entail waste reduction and development programs (Han et al. 2014; Lawrence et al. 2006). SMEs that have a strong environmental performance are discussed as financially successful in spite of resource constraints. In addition, the social aspect based on interaction with people also affects the success of social practices implemented by SMEs (Sodhi 2011; Theyel & Hofmann 2012; Welcomer 2011).

The main focus is on customers’ interests. Engagement in sustainable actions creates a positive image of the firm in the eyes of the customers, and they develop positive perceptions about the firm. A firm that takes the community into consideration before embarking on a particular project is able to develop positive relations with the community, and this enables the project to run smoothly due to reduced resistance (Brilius 2010; Theyel & Hofmann 2012; Welcomer 2011). SMEs achieve sustainability when they maintain good relations with other companies because they indulge in cooperation that is good for the survival of businesses (Brilius 2010; Moore & Manring 2009).

Subsequently, sustainable development consists of three components, namely sustainability in terms of economic, environmental/ecological, and social. It is related to a firm’s performance in one way or the others (Starik & Kanashiro 2013; Theyel & Hofmann 2012). Sustainable development may mean different things to different people in different contexts. It has commonly been defined as the kind of development that helps in meeting the current needs in a way that does not compromise future generation’s ability to achieve their needs (Avram & Kuhne 2008; McAdam 2000). In the context of SMEs, sustainable development refers to the ability of a firm to achieve the current developmental needs in a way that would assure its future developments (Brilius 2010; McAdam 2000). Most SMEs are always able to experience development in the early months of their initiation. However, as they grow in size, this development stagnates, or even depreciates, and this fact makes them unable to contribute to the growth of the country’s economy in a significant manner (Gilmore et al. 2001; Newby et al. 2003; Schumacker & Lomax 2004).

SMEs attempt to have the full concentration on the need for profitability while ignoring other social responsibilities; and this approach gives quick gains. However, a SME can reach a moment when those responsibilities become a significant barrier to the further development (Brilius 2010; Newby et al. 2003; Starik & Kanashiro 2013). For instance, SMEs are not able to manage their wastes, and when this continues without any measures from the responsible authorities, the wastes would reach shocking limits. Thus, responsible firms may be forced to revise their priorities for the sustainable development (Brilius 2010; Newby et al. 2003; Starik & Kanashiro 2013).

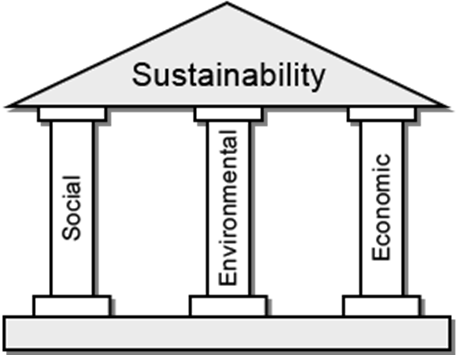

Three Pillars of Sustainability

The three pillars of sustainability include people (social pillar), profit (economic pillar), and planet (environmental pillar) (Brilius 2010; Theyel & Hofmann 2012; Welcomer 2011). The three pillars are very important in ensuring that there is sustainability, and any weakness in any of pillars would render the whole system unsustainable. This means that if a firm has excellent economic and environmental policies, but lacks clear policy on how to deal with social issues of its employees, the firm will be considered as unsustainable (Brilius 2010; Moore & Manring 2009; Theyel & Hofmann 2012; Welcomer 2011). These three pillars can be presented diagrammatically where sustainability is like a house with three corner stones (Figure 2.1).

Each of the three corner stones has its role in ensuring that the house remains stable. Any form of interference on either of the three pillars would always bring it down. This means that the three pillars must always be protected to achieve sustainability. Theories have been developed to help explain how these three pillars relate to one another, and how they can be supported through various operational activities of a firm (Asif et al. 2011; Han et al. 2014; Lawrence et al. 2006). The environment must be supportive for an SME’s activities in order to obtain profits. The economic pillar depends on the other two pillars of the natural environment and profitability. Society cannot exist without the support of the natural environment. The society also needs existence of business units in order to get jobs and acquire goods and services desired (Brilius 2010; Moore & Manring 2009; Theyel & Hofmann 2012; Welcomer 2011). Any form of compromise of the two pillars may render the entire system unsustainable, and this may lead to its collapse. Figure 2.2 shows the sustainability pillars as interdependent Entities.

Small and Medium Enterprise Sustainability

There are various versions of the term ‘business sustainability’. According to the complex approach, business sustainability is achieved when a business is able to align its needs and objectives with the external and internal environments’ developments, while attaining a dynamic balance (Moore & Manring 2008; Pojasek 2007). Thus, business sustainability is associated with creating the value for a business with the focus on utilising opportunities and monitoring business risks (Moore & Manring 2008; Oribu et al. 2014; Welcomer 2011). However, to achieve business sustainability, it is necessary to focus on efficient and advantageous practices that can be discussed as environmentally and socially friendly (Loucks, Martens & Cho 2010; Sarma et al. 2013).

It is important to state that when a business follows fundamental norms addressing the needs of an organisation and environments, it can achieve the business sustainability with the focus on the organisational culture and needs (Oribu et al. 2014; Pojasek 2007). Combining the specific business practices and initiatives to support sustainability, businesses support the principles of business sustainability associated with three pillars of sustainability (Arend 2014; Han et al. 2014). In this case, the role of the environmental initiatives on businesses’ decisions regarding sustainability is often more important than the impact of changes in the social and economic spheres (Oribu et al. 2014; Pojasek 2007; Welcomer 2011). In this context, to find the balance, organisations choose to refer to regulating activities associated with different types of sustainability, including the environmental, social, and economic areas and adapt them to the business environment (Arend 2014; Han et al. 2014).

SMEs need to shift to sustainability practices because of a range of advantages connected with the sustainable development. According to Pojasek (2007), sustainability is associated with the vision and mission of any business. Thus, as SMEs try to achieve objectives in the short- and long-term periods, they are prompted to engage in sustainability activities. Sustainability practices enable a business to meet its obligations towards stakeholders by embracing economic, social, and environmental spheres (Han et al. 2014; Moore & Manring 2009). Researchers state that the orientation to sustainability is important for SMEs because of the ability to address the social and environmental responsibilities (Hall, Daneke & Lenox 2010; Moore & Manring 2009). This approach leads to the creation of a more stolid organisation that can last for a long term because of avoiding ambiguous strategies and focusing on the clear advantages for the society, stakeholders, and environment (Han et al. 2014; Moore & Manring 2009).

Modern SMEs should be more informed, and the shift to sustainability leads to saving resources and increasing profitability. Subsequently, sustainability practices help to attain environmental sustainability, which has a positive effect on achieving SME’s sustainability (Theyel & Hofmann 2012; Welcomer 2011). SMEs that embrace sustainability avoid the costly rush of compliance because they are able to override the supply chain pressure and strict regulations. In addition, embracing sustainability enables SMEs to compete in new markets and have customer loyalty (Lawrence et al. 2006; Theyel & Hofmann 2012; Welcomer 2011).

From this perspective, having achieved sustainability or being oriented to the sustainable path, SMEs can operate within the industry more actively, guaranteeing their survival in the market. In this context, it is possible to rely on the long-term business success when economic, social, and environmental strategies of SMEs are perfectly balanced and interrelated (Hall et al. 2010; Sarma et al. 2013). Those SMEs that focus on sustainability create the value for their development while focusing on aligning with standards and trends (Hult 2011; Parrish 2010). As a result, more effective strategies are selected to stimulate the sustainable development, and SMEs can achieve the higher competitive advantage (Klewitz & Hansen 2014; Sarma et al. 2013).

Researchers also suggest that the important predictors of SMEs’ business sustainability are the specific dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing (Hult 2011; Parrish 2010). The reason is that such aspects of the entrepreneurs’ behaviour as proactiveness, innovativeness, and resource leveraging are predictors of SMEs’ business sustainability because if the leader is active, focused on innovative approaches, oriented to managing resources efficiently, and oriented to attracting stakeholders and meeting their interests, this leader can be discussed as following the path of sustainability in order to respond to the responsibilities in the environmental and social spheres (Hall et al. 2010; Lawrence et al. 2006).

Entrepreneurial Marketing

Conceptualisation of Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) is a complex process that is based on identifying aspects of the effective marketing and practices typical for successful entrepreneurs that can be used to conceptualise EM. Although the concept of EM was proposed only thirty years ago, it is important to focus on the aspects of its development and evolution (Becherer et al. 2008; Kraus et al. 2010). Conceptualisation of EM is associated with determining the components of the business success that can be used in order to discuss EM in a context of certain concepts. From this point, it is necessary to discuss EM in the context of entrepreneurship concepts and marketing concepts and with references to the progress of small scale businesses (Kurgun et al. 2011; Mort et al. 2008; Wallnofer & Hacklin 2013). Ionita and other researchers note that problems in development of EM is in the fact that the concept lies between marketing and entrepreneurship fields, and it opposes the basic principles of these fields (Ionita 2012; Morris et al. 2002).

According to Morris and the group of researchers, EM is a marketing strategy that uses innovation, pro-activeness, and risk taking initiatives to make use of limited resources within a firm to create awareness of the firm’s brand and products within the market (Morris et al. 2002). Thus, EM integrates opposite approaches used for marketing and entrepreneurship because the nonlinear entrepreneurial thinking is the basis on which traditional marketing models are utilized in EM (Collinson & Shaw 2001; Ionita 2012; Morris et al. 2002). Hills et al. (2008) also added to the discussion of the EM development while focusing on the evolution of EM.

Thus, according to researchers, evolution of EM is promoted by SMEs because of EM’s potential for the quick progress (Hills et al. 2008; Sole 2013). When SMEs have limited resources, they utilise EM to compete in specific industries with the aim of achieving competitive advantage by increasing the customer value (Hills et al. 2008; Kurgun et al. 2011). EM emerged from the realization of the heart of entrepreneurship and innovation to marketing (Barrett et al. 2000; Becherer et al. 2008; Mort et al. 2008; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). EM focuses on innovation as the means to drawing clients as opposed to searching for customer needs (Martin 2009; Stokes 2000).

Discussing EM, it is important to state that there are also radical approaches to discussing EM as a full integration of marketing and entrepreneurship (Morrish 2011; Mort et al. 2008). Small business owners develop their communication tools to attract potential investors and build effective interactions with investors using principles of EM (Morrish 2011; Wallnofer & Hacklin 2013). EM provides opportunities that enable a marketer to create the value for customers and build the customer equity. Furthermore, EM is very cost-effective because it relies on informal approaches to gather and deliver data. These methods help entrepreneurs to maintain competitive advantage over other competitors (Harrigan et al. 2011; Martin 2009; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). However, not all small business owners can be discussed as entrepreneurs (Hills et al. 2008; Ionita 2012; Kraus et al. 2010; Martin 2009). Thus, EM is a complex and inefficiently defined concept that is in a constant progress.

Entrepreneurial Marketing and Traditional Marketing

Operations typical for traditional marketing take place in a constant environment, and they oriented to meet well-defined customer needs. Thus, traditional marketing is based on an organisational philosophy or culture that stresses customer needs (Hills et al. 2008; Ionita 2012). Moreover, marketing is seen as a strategy that defines the competitive capability and survival of organisations in the marketplace. Furthermore, there is the marketing mix which is defined by the 4Ps, or 7Ps related to services marketing (Ionita 2012; Stokes 2000). In addition, marketing intelligence is important in each marketing domain because it entails the information gathering, dissemination, and response (Ionita 2012; Stokes 2000). In contrast, EM does not rely on customer needs for product development; rather, a product is created, and a market for it is pursued (Ionita 2012; Martin 2009; Stokes 2000).

Entrepreneurs are innovators, and they proactively design products to address an anticipated need. Unlike traditional marketing that was based on a strategy, EM is based on innovation. Entrepreneurs do not adopt the marketing mix, but instead refer to personal interaction with potential clients (Kurgun et al. 2011; Wallnofer & Hacklin 2013). Personal selling is important because an entrepreneur is able to get direct feedback about their products (Hills et al. 2008; Ionita 2012). Regarding market intelligence, entrepreneurs do not rely on formal methods for data collection; rather, they obtain feedback about their products through interaction with clients, and they are flexible to change. Table 2.1 shows the difference between Traditional Marketing vs. EM.

Table 2.1. Difference between Traditional Marketing and Entrepreneurial Marketing

Entrepreneurial Marketing Dimensions

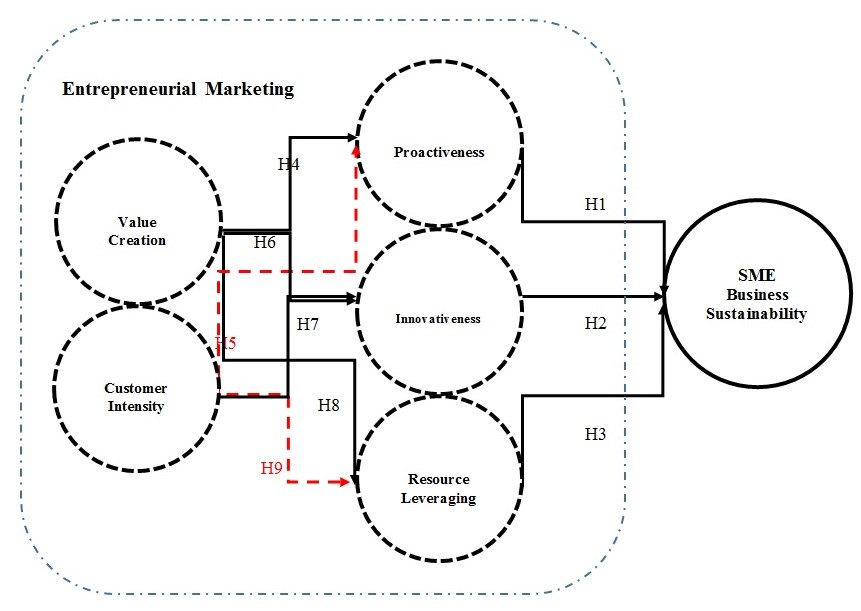

Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) is based on seven dimensions as shown in Figure 2.3, but for the purposes of this study, only five dimensions will be discussed as two of the dimensions will be excluded and they will not be considered in this study. These dimensions are Calculated Risk Taking and Opportunity Focus. The reason is that Calculated Risk Taking is not completely associated with sustainability in small organisations because this dimension relies on making decisions in large organisations where outcomes of actions are difficult to be predicted, rather than in small organisations (Gaweł 2012, p. 7; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013, p. 212). As a result, according to Morris and the other researchers, Calculated Risk Taking is directly associated with mitigating identified risks in mature institutions rather than with developing sustainability in small organisations (Morris et al. 2002, p. 7; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013, p. 209). Furthermore, Opportunity Focus also has no favourable relationship with sustainability because it is directly associated with entrepreneurship and marketing strategies in terms of determining effective marketing positions with the help of the environment scanning procedures, but this approach does not explain the connection of this dimension with sustainability (Morris et al. 2002, p. 6; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013, p. 212). In spite of the fact that Opportunity Focus is indirectly associated with the economic aspect of sustainability, it does not relate to the social and environmental aspects; thus, it does not contribute to the purpose of this study. The remaining five dimensions are proactiveness, innovativeness, resource leveraging, value creation, and customer intensity that are explained accordingly.

Proactiveness

Proactiveness is a person’s behaviour that has the potential to bring about the change. Entrepreneurs should be proactive to create new products and a market for them. Proactiveness has a positive effect on both individual and organisational performance (Gaweł 2012; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Entrepreneurs adopt proactiveness as a means of standing out from all other competitors because it entails acting in anticipation of future demands. Proactive entrepreneurs utilise market intelligence by gathering information from customers and fellow competitors on unarticulated and unmet needs of the population (Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). This dimension entails the identification of an opportunity and exploiting the opportunity to obtain maximal financial benefits.

Innovativeness

Innovativeness depends on a search for creative, unique, and new solutions to meet customer needs, or solve problems (Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Innovation is a driving force in EM because successful SMEs aim to improve current and past products by developing a new and different product. SMEs rely on improving current relations between firms and their customers and on generating the specific market knowledge (Becherer et al. 2008; Gaweł 2012). Innovativeness is important because it enables SMEs to gain and maintain the competitive advantage (Harrigan et al. 2011; Morrish 2011). Thus, innovativeness in EM means the use of the technological progress and experimentation to influence the improvement of products and processes (Gaweł 2012; Theyel & Hofmann 2012).

Resource Leveraging

This is an important dimension of entrepreneurial marketing that advocates for doing more with less (Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Embracing this dimension enables firms to optimally utilise whatever that is available to develop a market base. SMEs work effectively when they refer to resource leveraging because it is associated with making optimal use of the limited resources (Gaweł, 2012; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Thus, the limit of resources demands a proactive response to ensure that the firm is still able to make profits. As a result, the focus is on recognising resources effectively and on their choice to achieve the maximum (Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013).

Value Creation

Value creation is an ultimate objective for each SME. If a firm is not able to create value, then its market success is under question (Gaweł, 2012; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Value creation is important for marketers as a process of finding new sources in order to contribute to the existing customer value. Furthermore, the value creation depends on a choice of unique combinations of resources to gain profits (Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). As a result, value creation is also based on the marketer’s ability to recognise and use provided opportunities in order to add value to the business progress (Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013).

Customer Intensity

Customer intensity is a dimension that explains an entrepreneur’s efforts to attract and retain clients. This dimension also explains the focus on customer as the customer-centric relationships (Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Researchers link the success to the customer intensity, but the excessive focus on customers prevents developing innovation and interferes with the market equilibrium. However, marketers refer to changing customer circumstances and managing dynamic customer relationships because it is a way to the market success (Becherer et al. 2008; Morris et al. 2002; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013).

Entrepreneurial Marketing, Sustainability and Research Gaps

The previous studies in SMEs’ sustainability and entrepreneurial marketing can be divided into three groups that are the studies in sustainability, studies in EM, and studies in the relationship between SMEs’ sustainability and entrepreneurial marketing. The last group of studies is the smallest one because there is a lack of the research on the influence of entrepreneurial marketing and EM dimensions on sustainability of SMEs (Dobni 2010; Guido, Marcati & Peluso 2011). The problem is in the fact that researchers mention and describe some aspects of entrepreneurial marketing as important for developing sustainability in SMEs, but they did not focus on exploring the clear relationship between the variables to state that EM dimensions can influence the process of achieving business sustainability in SMEs significantly (Dobni 2010; Guido et al. 2011; Moore & Manring 2009).

The division of the previous studies in the field in groups allows the discussion of the research gap related to each important area. Past studies on sustainability, entrepreneurial marketing, and on the relationship between SMEs’ sustainability and entrepreneurial marketing are presented in three separate tables to demonstrate the research gap and be discussed in detail. Table 2.2 presents past studies in the field of SMEs’ sustainability. Table 2.3 presents past studies in the field of entrepreneurial marketing. Table 2.4 presents past studies on the relationship between SMEs’ sustainability and entrepreneurial marketing. Referring to separate tables, it is possible to analyse the aspects of sustainability and entrepreneurial marketing that most discussed by researchers. The obvious gap in the researches is the limited discussion of the role of EM dimensions in developing SMEs’ sustainability in spite of the fact that researchers mentioned proactiveness, innovation, resource leveraging related to EM in the context of the SME’s progress and competitive advantage (Avram & Kuhne 2008; Guido et al. 2011; Loucks, Martens & Cho 2010; Moore & Manring 2009).

Table 2.2 presents past studies in the field of SMEs’ sustainability. If Atkinson discussed SMEs’ sustainability with the focus on criteria selected to measure it, Newby, Watson, and Woodliff chose to discuss sustainability while focusing on business tendencies that can influence its development (Atkinson 2000; Newby et al. 2003). Bansal and Clelland proposed the discussion of sustainability with references to the legitimacy factor (Bansal & Clelland 2004). The role of sustainability in the process of creating the value was examined by Sull and Escobari (Sull & Escobari 2004). However, the complex analysis of the role of sustainability for the business development was proposed only by Berns and the group of researchers who developed the complex company analysis related to the issue of sustainability in order to understand the role of its pillars (Berns et al. 2009). Nkamnebe also added to the discussion of SMEs’ sustainability while focusing on the role of external pressures, and these findings were supported by Guido Marcati, and Peluso’s study because the researchers paid attention to the managers’ readiness to sustainable practices (Guido et al. 2011; Nkamnebe 2009). Thus, researchers are inclined to emphasise the importance of sustainability in enhancing the value of a business and increasing competitive advantage (Loucks, Martens & Cho 2010; Moore & Manring 2009; Starik & Kanashiro 2013).

Still, in spite of the presence of many researches on SMEs’ sustainability and sustainability aspects, the majority of researches are qualitative, and there is a lack of empirical research in the field to discuss social, economic, environmental aspects of sustainability (Arend 2014; Parrish 2010). There is no adequate scientific evidence to state how sustainability brings about the increased value in terms of better financial performance. There is a limited empirical research to examine business sustainability or sustainability as a whole (Arend 2014; Kraus & Britzelmaier 2012; Müller & Pfleger 2014). Most of the research on sustainability with regard to environmental and social perspectives has focused on large multi-national firms (Berns et al. 2009; Müller & Pfleger 2014). Yet, there is insufficient scientific literature on the engagement in sustainability practices by SMEs, and how these firms operate to meet environmental and social needs (Guido et al. 2011; Müller & Pfleger 2014). In addition, there is little information on the relationships between sustainability practices, innovation, and stakeholder interaction (Avram & Kuhne 2008; Bansal & Clelland 2004). From this point, even if researchers mention innovation and proactiveness while discussing sustainability, they do not discuss these EM dimensions as predictors of sustainability (Avram & Kuhne 2008; Guido et al. 2011; Loucks, Martens & Cho 2010; Moore & Manring 2009). Furthermore, many of the past studies have focused on SMEs in the Western countries, and there is a limited focus on the other countries (Avram & Kuhne 2008; Bansal & Clelland 2004). Hence, this is the reason why the present study aims to focus on SMEs’ sustainability in Saudi Arabia.

Table 2.2. Past Studies in the Field of SMEs’ Sustainability

Past studies on EM present the active discussion of EM dimensions as influential for the efficient growth of SMEs, as it is discussed in Table 2.3 (Becherer, Haynes & Helms 2008; Beverland, Farrelly & Woodhatch 2007). The topic of EM was covered by Mitchelmore and Rowley, Rezvani and Khazaei, Morrish, and Mort, Weerawardena, and Liesch in their researches, but the authors proposed only the review of the literature on EM, without focusing on its relationship to sustainability (Mitchelmore & Rowley 2010; Morrish, 2011; Mort, Weerawardena, & Liesch 2012; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Thus, EM provides entrepreneurs with a lot of strategies and approaches to develop their businesses because of the focus on innovation, attraction of customers, and value creation (Harrigan, Ramsey & Ibbotson 2011; Jones & Rowley 2009; Mitra, Dhar & Agrawal 2008). However, there is a lack of literature on the connection between entrepreneurship and sustainability and on the link of EM and sustainability, and there is a great need to understand the relationship between the environment and changes in the approaches to entrepreneurship (Bansal & Clelland, 2004; Bettiol, Di Maria & Finotto 2012; Hills & Hultman 2011). There are only indirect discussions of the relationship between EM dimensions and SMEs’ sustainability (Bettiol, Di Maria & Finotto 2012; Jones & Rowley 2009; Lawrence et al. 2006). In this context, it is also important to state that there is a lack of studies on entrepreneurial marketing dimensions and their relations to each other (Gilmore 2011; Kurgun et al. 2011; Morris et al. 2002). Therefore, there is a lack of studies on the relationship of these EM dimensions and aspects of sustainability and on EM dimensions’ correlation.

Table 2.3. Past Studies in the Field of Entrepreneurial Marketing

Table 2.4 presents past studies on the relationship between EM and SMEs’ sustainability. The number of these studies is limited because of the obvious gap in the field of research. It was highlighted by researchers that SMEs need to be proactive, innovative, and focused on leveraging resources; however, there were no studies to support the idea of improved sustainability as a result of the focus on proactiveness, innovativeness, and leveraging resources as EM dimensions (Franco et al. 2014; Kickul & Gundry 2002). The empirical research on EM dimensions as predictive factors of SME business sustainability is necessary because there are limited sources mentioning the advantages of EM dimensions to be used by SMEs to increase their competitive advantage and sustainability. Thus, there is a lack of researches to discuss the links between entrepreneurship and sustainability, but the current researches are important to formulate assumptions regarding the influence of EM dimensions on SMEs’ sustainability (Gawel 2012; Hacioglu et al. 2012; Sarma et al. 2013).

Table 2.4. Past Studies on the Relationship between SMEs’ Sustainability and Entrepreneurial Marketing

Past studies indicate the role of innovativeness, proactiveness, and resource leveraging for SME’s sustainability. These factors are indirectly discussed as predictors of the company’s sustainable development while referring to the results of the qualitative studies (Loucks, Martens & Cho 2010; Moore & Manring 2009). Nevertheless, these factors are really discussed in their relation to EM, thus, researchers do not link directly EM dimensions with the issue of sustainability in spite of the presence of indirect discussions. The lack of the empirical research on the relationship between EM and SME’s sustainability and absence of the clear discussion of the role of EM dimensions for sustainable development indicates that the additional study is necessary to determine and explain the assumed relationship between EM and SME’s sustainability (Gawel 2012; Hacioglu et al. 2012; Sarma et al. 2013). Thus, this research seeks to provide more insights in the topic on sustainability and relationship between EM and sustainable development of SMEs in Saudi Arabia.

Small and Medium Enterprises

SMEs are common for both developed and developing economies where SMEs play an important role in the economic growth of a country. New firms rarely start as large corporate organisations. In most of the case, new firms start as small and medium sized firms (McAdam 2000; Moore & Manring 2009). This fact means that in every country, SMEs exist with new firms entering the market while creating the better value in the existing market (Motwani, Levenburg & Schwarz 2006). SMEs usually form the majority of registered firms in both developed and developing countries and employ a great number of people. However, the performance of SMEs is different in these economies. The contribution of SMEs to the national economic growth in developed countries is more than 80% of production (Brilius 2010; Guido et al. 2011; Moore & Manring 2009). Thus, the performance of SMEs in developed countries is better than their performance in developing countries (Brilius 2010; Moore & Manring 2009; Sharma 2011). This could be attributed to the fact that SMEs are the main constituents in the Western economies. Over time, traditional factors of success have been changed with the other factors, such as innovation due to radical changes and increased global competition (Brilius 2010; Moore & Manring 2009). These changes have prompted the SMEs to utilize entrepreneurial dimensions with the aim to attain competitive advantage, and subsequently, sustainability.

In developing countries, SMEs are varied in the choice of products and services offered; hence, they contribute towards a diversified economy that subsequently expands industrial production. In addition, SMEs are a source of income because they offer employment to more than 50% of a developing country’s population (Bahaddad et al. 2013; The EU-GCC Chamber Forum 2010). Thus, SMEs are entities that improve the competitiveness, and support the restructuring of developing countries’ economies (Alsaleh 2012; Asif et al. 2011). In developing countries, for example Africa, the poor survival and performance of SMEs is associated with weak economies; hence, these countries have a weak human and social development framework. However, SMEs have limited resources to take part in the environmental sustainability and support the green growth recognised as a strategy that promotes the national economic growth and development, while simultaneously ensuring environmental sustainability (Bahaddad et al. 2013; The EU-GCC Chamber Forum 2010). The reason is that developing countries have poor policies and regulatory frameworks that negatively influence sustainability of SMEs. These poor policies influence the access to credit, fail to support markets for products, do not resolve the lack of adequate training facilities and up-to-date technologies. This limitation in resources makes it difficult for an SME to actively take opportunities that require the use of resources in the attainment of sustainability, for example corporate social responsibility (Alsaleh 2012; The EU-GCC Chamber Forum 2010). In developing countries, therefore, it becomes difficult for SMEs to actively get involved in external social and environmental dimensions.

SMEs are important for the development and growth of Saudi Arabia because SMEs form about 92 percent of businesses in the country (Alsaleh 2012; The EU-GCC Chamber Forum 2010). However, SMEs’ contribution to the country’s economy is only about 33% of the GDP, and the period of SMEs’ operations within the market is only about seven years (Alsaleh 2012; The EU-GCC Chamber Forum 2010). In Saudi Arabia, governments declare that they provide the financial support to SMEs to give them the opportunity to attain the development plans, strategic goals, and deliver high-quality goods. However, bureaucracy is a main barrier to receive the necessary support. The activities of governmental organisations are influential for starting SMEs, but they are main obstacles in the country to develop businesses (Allurentis Limited 2013; Asamari et al. 2013). The potential of SMEs is admitted, but the government avoids supporting SMEs directly in spite of a range of proposed programs (Bahaddad et al. 2013; The EU-GCC Chamber Forum 2010).

Along with the government’s initiatives, commercial banks are important financial suppliers to SMEs, and the services of the accountant are a crucial element in meeting the needs of SMEs because the accountant is labelled as the ‘most trusted adviser’ (Allurentis Limited 2013; Asamari et al. 2013). However, even if SMEs receive the advice on such issues as taxation, financial management and budgeting, succession, and debt administration, there is no guarantee that banks will provide credits to SMEs (Allurentis Limited 2013; Asamari et al. 2013). Commercial banks avoid supporting SMEs in Saudi Arabia, and it is a barrier for the development. As a result, SMEs cannot rely on the effective use of innovation and on the efficient business planning (Alsaleh 2012; The EU-GCC Chamber Forum 2010).

Summary

Chapter II presents the discussion of the basic constructs and concepts referenced in the research. Institutional and Contingency Theories are discussed as the framework to focus on the idea of sustainability. The chapter also presents the sustainability concept supported with the discussion of the Small and Medium Enterprise sustainability. The definition of entrepreneurial marketing is also provided in the chapter. Five EM dimensions are discussed as appropriate to be studied in the research. The chapter also provides the detailed discussion of the gap in the existing research on the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing and sustainability. The chapter ends with the discussion of the literature on Small and Medium Enterprises in Saudi Arabia.

Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis

Introduction

This chapter has three sections that aim to discuss and elaborate the research hypotheses. The first section entails a detailed discussion of the relationship between variables based on supporting scientific literature. In this section, there is also a brief discussion about the interaction of these variables, in terms of how one influences another. The second section is an illustration of a research framework based on the variables. The last section is a summary of the chapter.

Definition and Operationalization of Constructs

Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) business sustainability is defined as an ability to maintain the operations of a business over time, progressively leading to growth and development without manipulating the needs of further generations (Brilius 2010; Starik & Kanashiro, 2013). In literature, sustainability is operationalised or measured by evaluating sustainability aspects according to Cronbach’s alpha (Delai & Takahashi 2011; Lawrence et al. 2006). In this study, SME business sustainability is operationalised with references to the discussion of Economic, Social, and Environmental components or pillars as the parts of one construct of business sustainability. Thus, SME business sustainability is measured by adapting the Likert scale measures and focusing on Cronbach’s alpha in order to discuss Economic, Social, and Environmental pillars as components of the complex construct of sustainability. It is possible to discuss SME business sustainability only with references to all its aspects that are closely connected in businesses’ strategies (Sarma et al. 2013).

Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) is defined as a set of processes for creating the value to customers and for organising customer relationships to gain profits with the focus on innovativeness and proactiveness (Kraus et al. 2010; Morris et al. 2002). In literature, EM is operationalised or measured with the focus on EM dimensions and according to Cronbach’s alpha (Kraus et al. 2010; Morris et al. 2002). In this study, EM is measured with references to its dimensions.

Proactiveness is the EM dimension that refers to the anticipation of future demands of firms related to market opportunities and environment (Morris et al. 2002). In literature, proactiveness is measured by the number of opportunities taken by the businessman (Gawel 2012). In this study, proactiveness is measured with the focus on managers’ choice of new projects and opportunities.

Innovativeness is the EM dimension that refers to the mechanism of searching for creative, unique, and new products, services, solutions, technologies and processes (Morris et al. 2002). In literature, innovativeness is operationalised and measured by the number of innovative approaches taken by businessmen (Gawel 2012). In this study, innovativeness is measured by the readiness to adapt innovation to SMEs.

Resources Leveraging is the EM dimension that refers to the means for unrecognized resources that not has been used in the past while considering making the optimal use of the current limited resources (Morris et al. 2002). In literature, resources leveraging is operationalised with references to the optimal solutions (Morris et al. 2002). In this study, resources leveraging is measured with references to managers’ success in using resources efficiently.

Value creation is the EM dimension that refers to the ability to find and combine different and unique resources that are undiscovered, in order to produce value for customers (Morris et al. 2002). In literature, value creation is measured by the overall profitability of the business (Morris et al. 2002). In this study, value creation is measured by adapting the managers’ vision of their successes in value creation.

Customer Intensity is the EM dimension that refers to ways of customer acquisition, retentions and development that explains an entrepreneur’s efforts to provide a certain level of customer investment and customization (Morris et al. 2002). In literature, customer intensity is measured with the number of attracted customers (Morris et al. 2002). In this study, customer intensity is measured according to managerial strategies regarding customization.

Research Framework

A research framework is proposed based on literature and identified research gaps and it is shown in Figure 3.1. The research framework shows the inter-relationships between the identified dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing and the indirect and direct effects of entrepreneurial marketing on SME business sustainability.

Value creation within a firm is obtained through innovation which subsequently is associated with customer intensity in that customers give feedback based on their preferences, and this contributes to the innovation. This feedback cannot be realized without the leveraging of resources using a proactive approach. When value creation is continually achieved, a firm’s growth is sustained as well as its competitive advantage. Customer intensity in itself is a resource that is leveraged to inform a firm about prevailing gaps that can be addressed (Anderson & Swaminathan 2011; Arend 2014; Sawhney et al. 2005). Initially, customers had a passive role and merely received the products produced by various firms. Proactiveness, innovation and resource leveraging are directly linked to value creation because the innovation of a product instigated from customer intensity or a firm’s proactiveness requires the leveraging of resources to finalize the innovation, and subsequently create value.

Hypotheses Development

The following section elaborates and justifies each relationship between the constructs, and formulates the research hypotheses.

Proactiveness and Sustainability

Gawel (2012) focuses on demonstrating a positive relationship between proactiveness as a measure of entrepreneurship orientation and sustainability. This relationship is evident from the mere nature of the definition of these terms. Whereas proactiveness is an activity aimed at pursuing greater profits, sustainability is linked to efficiency and equality, which are determined by the economic, social and environmental aspects of a society (Gawel 2012; Morris et al. 2002). Proactiveness entails the decisions, processes and practices within a firm that meet not only the firm’s needs, but the needs of the larger society. Subsequently, this leads to creation of balance between people, planet and profit.

Mitra et al. (2008) further support the establishment of this balance by discussing proactiveness in light of addressing environmental challenges with the aim of achieving equilibrium with nature. Despite the much emphasis on the relationship between proactiveness and sustainability, little has been studied with regard to these variables. Mitra et al. (2008) have used the Institutional Theory to emphasize the need for proactiveness in achieving sustainability. Proactive firm practices result in an increased utilization of raw materials; thus, reduced operation costs (Mitra et al. 2008; Moore & Manring 2009). Subsequently, the firm gains a greener corporate image that increases its market share and achieves sustainability. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Proactiveness has a positive effect on business sustainability of small and medium enterprises.

Innovativeness and Sustainability

In the current world where businesses are competitive in order to grow and develop, innovation becomes paramount. Vanormelingen & Cassiman (2013) argued that sustainability and survival for individual firms are derived by innovation which is a key element for economy growth and company’s success, and there for they showing a positive relationship between innovation and sustainability. Vrontis et al. (2012) support this further by indicating the essence of innovation in achieving competitive advantage, which is crucial for the growth and development of any firm. Innovation is deemed to meet the changing demands of the customers and the larger society. Therefore, such a business is able to maintain its market share as it attempts to attract new clients, leading to sustainability and growth. In addition to Vrontis et al. (2012) support for such relationship between innovation and sustainability, Bresciani et al. (2011) furthermore confirms that innovation are crucial point to achieve business sustainability and therefore companies can survive and compete in the global economy.

In the continually evolving market world, innovation remains a distinctive feature for sustainability in business. Dobni (2010) shows a positive relationship between innovativeness and sustainability by indicating that innovation is a key role in achieving escalating profit margins and growth within an organization. In the 2005 Arthur D study, it was found out that innovation is associated with increased sales and returns that enable a business to reach sustainability by engaging in actives that meet the need of the larger society (cited in Dobni 2010, p. 49). Innovation is associated with value creation, and when a firm continuously enhances the value of its products through innovation, it is able to maintain its competitive advantage and break through to the next level. Other studies also support the relationship between innovation and sustainability. For instance, Gawel (2012) stressed that innovation involves bringing and presenting out new products, services, solutions, and technologies into the marketplace can be so helpful in the realization of sustainability. On the other hand, Hills and Hultman put forward that innovation as dimension of the entrepreneurial orientation conduct is a process which is characterized as a holistic as well as complementary fundamental to achieve sustainability and success in the organization (Hills & Hultman 2011).

There is also evidence from the scientific literature that innovativeness are a vehicle to reach sustainability in the context of SMEs. For example, Gilmore (2009) indicate that the numerous undertaken processes and innovations may be necessary to obtain sustainability and future growth of small business. And this can be achieved through the ability to provide target customers with latest new methods, promotions, distributions channels including supports which enables business to create additional value by having increased brand awareness and levels of efficiency. Kickul and Gundry (2002) furthermore support this by arguing that continuous innovation in the market and the response to customers’ requirements as well as competitors, are essential for SMEs to sustain and survive (Morris et al. 2002). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Innovativeness has a positive effect on business sustainability of small and medium enterprises.

Resource Leveraging and Sustainability

Wallnofer & Hacklin (2013) emphasize the positive association between resource leveraging and sustainability. These authors state that resources in the context of both internal and external resources are imperative in enhancing business survivability and sustainability. Resource leveraging can be viewed from two angles; during the initial stages of a business model, and when a business aims at gaining competitive advantage. Regardless of business stage, what a business owns is vital if external stakeholders are to collaborate with the business to ensure its growth and development (Kurgun et al. 2011; Webb et al. 2011). Dobni (2010) emphasizes that the people within an organization are drivers of innovation, but this is determined by their thoughts and actions. Despite the fact that employees within an organization are sources of value creation, alone they cannot successfully innovate because the leveraging of resources is vital. Often, an organization is not able to succeed on its own; hence, the need for resource leveraging if sustainability is to be achieved through innovation.

Innovation, unlike creativity, requires the mobilization of external partners to promote organizational learning. The innovation process is dynamic, and for a company to sustain its competitive advantage, it not only needs to develop new products, but should also adapt reflex-adaptability and improvement on current internal capabilities (Dobni 2010; Gawel 2012; Morris et al.). Resource leveraging is positively related to sustainability because knowledge, skills and funds are important for a firm to progressively sustain its innovative environment that is imperative for the business’ survival (Gawel 2012; Rezvani & Khazaei 2013). Technology, cost structures and distribution systems are equally important in enabling a firm to maintain its competitive advantage in an incessantly changing business world. Adopting a transformational approach in a firm is vital because it helps firms to keep themselves updated with the societies and cultures as they evolve, and subsequently alter the needs of the people.