Introduction

Hersey-Blanchard Leadership model is described as complex, fragmented, and contradictory (Blackwell and Gibson 1998). In general, leadership can be described as a process of social influence through which one person is able to enlist the aid of others in reaching a goal. A number of activities are included in the leadership role, and it is illuminating to look at these activities in relation to the organizational functions of internal maintenance and external adaptability (Price, 2004). Hersey-Blanchard Leadership model was developed at the late 1960s and described in the book Management of Organizational Behavior. Hersey and Blanchard describe the behavioral options available to leaders for carrying out the guidance and motivation functions, situational variable and their impact on organizations, employees and society.

Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership

Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard state that situational leadership roles are temporary roles designated for some particular task, and the emergence of the role is based on the special ability of an individual with respect to the task at hand (Hersey and Blanchard 1977). Thus, if the group is undertaking a hunt of some particular animal, one or more members of the group might be given leadership roles because of their experience and expertise at hunting that particular animal. Those leadership responsibilities and authority would last only as long as the group was focused on the particular activity (Hersey and Blanchard 1977). According to this model,

Leaders should adapt their style to follower development style (or ‘maturity’), based on how ready and willing the follower is to perform required tasks (that is, their competence and motivation) (Situational Leadership 2007).

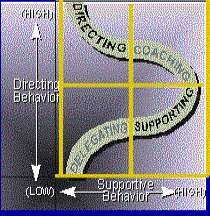

Situational leadership theory directly addresses subordinate changes as an aspect of situational contingencies. The fact that situational leadership theory is primarily a training model, whose authors have not sought extensive empirical validation, made it possible to include change factors that are relatively costly to address in organizational research. In any case, situational leadership theory builds a prescription for supervisory behavior based on the stage of development (or maturity) of the subordinate who is the target of the leader’s influence efforts (Hersey and Blanchard 1977). The model classifies subordinate maturity on two dimensions; “psychological maturity,” assessing the follower’s commitment, motivation, and willingness to accept responsibility; and “job maturity,” which captures the follower’s experience, knowledge, and understanding of task requirements. The four leadership styles are:

- telling/directing,

- selling/coaching,

- participating/supporting,

- delegating/observing (Hersey et al 1980) (see Appendix, Graph 1).

High psychological maturity reflects a willingness to undertake responsible tasks, whereas high job maturity reflects the ability to accomplish such tasks. Thus, a subordinate could be willing or unwilling and able or unable with the lowest level of overall maturity being the unwilling and unable subordinate, followed by the willing but unable, then the able but unwilling, and the highest level of maturity being both willing and able (Hersey and Blanchard 1977). The superior’s behavioral options include the now familiar task-oriented, directive, and structuring behaviors and the relationship-oriented, supportive, and participative behaviors.

Treated as independent aspects of the leader’s style, high levels of either, both, or neither behavior could be adopted by the superior (Hersey and Blanchard 1977). High levels of directive, task behavior combined with a low level of paticipative, relationship behavior is referred to as “telling”; high task and high relationship is “selling”; high relationship and low task is “participating”; and low levels of both task and relationship behavior is “delegating.” (Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Leadership 2007).

As the subordinate matures, the leader moves from telling to selling to participation and eventually to delegating where a capable and committed subordinate is encouraged to take responsibility for decisions and action. In practice, this model includes various rating scales for both superior and subordinate to assess levels of subordinate maturity. The model is used alone to improve leader-follower communications or in conjunction with other goal setting plans, such as management by objectives (Situational Leadership 2007).

Impact on Organizations and Employees

The primary function that an organization must achieve is the regularization of activities to provide a stable base for productive operation. If one person could accomplish a job, the creation or assignment of a group would not be warranted. Applied to organizations, Hersey-Blanchard Leadership model helps to analyze and examine impact of situational variable on employees and performance. It is known fact that groups require coordination of the efforts of their members (Polleys, 2002). The time and energy spent in that coordination are diverted from productive activity. Organizations, which are groups of groups, demand even greater resources applied to coordination. Hersey and Blanchard explain the role of ‘readiness’, in relation to one’s job:

- the readiness factor (innate ability, education, training, and experience), which reflects a person’s capability for performing the job;

- the psychological maturity factor, which is associated with an individual’s self-confidence, desire for achievement, and willingness to accept responsibility” (Einstein and Humphreys 2001, p. 48).

Nonetheless, most of the productive activities in modern society cannot be accomplished by one person working alone. Organizations are essential to the realization of the goals of productive endeavor, and leaders are essential to organizational coordination (Einstein and Humphreys 2001, p. 48).

The situational parameters common across theories are those that contribute to a general dimension of clarity, predictability, and certainty. The relationship of leader action to situational demand depends on the perspective taken (Polleys, 2002). The leader-oriented theories argue for greater consultation and participation when that will facilitate creativity and/or acceptance on the part of followers. The subordinate-oriented theories stress the importance of supplying followers with cognitive and emotional resources necessary to work effectively, but which are otherwise missing in the environment. Those resources include information, direction, counseling, support, and encouragement. The impact on employees can be explained by combination of different styles and situations: “Picking the appropriate style follows a life-cycle approach in the relationship between the leader and the subordinate(s)” (Einstein and Humphreys 2001, p. 48).

The facts mentioned above allow to say that within the organizational context, leadership involves direction and guidance, motivation and encouragement, support and reinforcement, problem solving and creativity. Different environments and different people require a different mix of emphases among these functions (Polleys, 2002). Subordinate development involves leadership behaviors that progressively increase subordinate autonomy, that is, from direction to participation to delegation. The development of subordinate autonomy involves a process of mutual influence in which leader and follower roles are negotiated.

Individualized considerations are also important for Hersey and Blanchard. This factor measures the degree to which the leader treats each follower in a way that is equitable and satisfying, but differentiated from the way other followers are treated. Another aspect of this factor is that the leader’s behaviors raise the maturity of the subordinate’s needs by providing challenges and learning opportunities. The actions of leaders or followers are determined by their expectations about the results of those actions (Einstein and Humphreys 2001).

Examples include a leader’s analysis of the relative utility of various behaviors to motivate and guide the work of subordinates, the choice of influence tactics, and decisions about how much autonomy a subordinate is capable of handling. It is assumed that the expectations that the leader holds will determine the behaviors or strategies chosen. Research indicates that expectancies do, in fact, influence leader behavior (Einstein and Humphreys 2001). It is important to note that these leader expectancies are based on various kinds of judgments about subordinates, such as, needs, maturity, ability, and so forth. Although perceptions of leaders and followers are integral parts of many theories, until recently, very little attention had been paid to studying the processes by which interpersonal judgments are made. In fact, for the first 5 or so decades of research on leadership, it was simply assumed that reports and judgments were accurate reflections of reality (Lagone and Rohs 2003)..

Subordinate guidance and development occurs in the context of a personal relationship. The personal and emotional basis for the leader-follower relationship should not be understated. In a study of substitutes for leadership, although features of the subordinate’s environment, such as peer relationships or organizational climate, may have a strong impact on the subordinate’s satisfaction and motivation, such factors do not lessen the strength of the leader’s effects on the follower (Stirling, 1998). Feedback from one’s superior had the strongest effect on overall job satisfaction, regardless of what other feedback sources were available. The relationship of leader and follower appears to be one of sufficient emotional weight that, regardless of other factors operating in the situation, the leader’s acts will have great import for a subordinate. (Sogunro, 1998).

Impact of Society

When groups or organizations are operating in less predictable environments that call for an emphasis on external adaptability, the leader’s crucial functions entail problem solving and innovation. In some groups or societies, the relative distinctions between individuals are quite minor, and the system is very simple. Some individuals have a great deal more power than others, and one person’s income could be thousands of times that of another. The positive functions of status are vital to the sustenance of any organization (Hersey and Blanchard 1977). If the tasks that faced a social unit were equally important to the unit’s survival, there would be no need to differentiate its members. For instance, any member could do any job, if all jobs were equal in their impact. However, because individuals differ in their abilities, and because the tasks that a social unit faces differ in terms of their importance, it becomes very significant for an organization to assign its most capable members to its most important tasks (Einstein and Humphreys 2001).

Hersey-Blanchard Leadership model allows to explain motivation and the consequences of the action also have effects on the perception of internal motivation. Segriovanni and Glickman (2006) question: do the positive and negative consequences that ensue from the act suggest that the actor would want to cause those consequences? Another way that consequences affect judgment is related to the essential egocentricity of human beings, that is, things that affect us directly have greater impact on our judgments than those that are irrelevant. Thus, when another person’s act has positive or negative consequences for the observer ), the observer is more likely to conclude that the act was intentional, with resultant positive or negative evaluations of the actor. This effect is enhanced if the observer also believes that he or she was the intended target of the action (personalism) (Segriovanni and Glickman, 2006).

Criticism

In spite of apparent benefits of Hersey-Blanchard Leadership model there is a lot of criticism concerning laminations and drawbacks of this approach. Critics admit that the very concept of leadership is defined by the relationship between the leader and the led (Price, 2004). The preponderance of leadership research focuses on the factors that influence that relationship. As the social exchange theories make clear, relationships are built on mutually rewarding exchanges, involving the satisfaction of the needs of both parties. One of the leader’s most important responsibilities is the development and direction of subordinates’ goal-oriented capabilities and activities (Mabey and Salaman, 2003).

The literature sometimes appears scattered on how the leader can best accomplish this function. However, greater clarity can be gained through the recognition that the leader-follower relationships are dynamic over time and that no two relationships are the same. The supervisory behaviors that work for one subordinate may not work for another or even for that subordinate at another stage of development. Although effective in the proper situation, contingent reward supervision is limited by the nature of both the task and the characteristics of the subordinate. In order for behaviorally oriented interventions to be productive, tasks must have sufficient structure and clarity to allow for careful pinpointing and surveillance of desirable behaviors, without the encouragement of unwanted behaviors or the suppression of desirable behaviors not rewarded (Mabey and Salaman, 2003). Secondly, the contingency theories of supervision indicate that although high levels of leader ‘directiveness’ can be helpful when subordinates are confronted with tasks beyond their current capabilities, such close monitoring and instruction can become counterproductive when subordinates find their tasks within their capabilities (Mabey and Salaman, 2003).

There is considerable overlap across the theories on the specification of critical situational characteristics. All the models include a variable that could be integrated under the broad rubric of structure or predictability (Segriovanni and Glickman 2003). The contingency model, path-goal theory, normative decision theory, and the multiple influence model are quite explicit in including variables that relate to the clarity and certainty of the task requirements and goal paths (Segriovanni and Glickman 2003). A reflection on the “subordinate task maturity” variable in situational leadership theory reveals that variable to have a very high similarity to the degree of structure in path-goal theory in particular. Both refer to how well the subordinate understands the correct actions to take in accomplishing the task. Variables like task structure are also included in Yukl’s multiple linkage model, but are not highlighted relative to other situational variables (Segriovanni and Glickman 2003).

Conclusion

In spite of certain laminations, the Hersey-Blanchard model proposes a lot of opportunities for organizations to adapt and respond effectively to changing environment. In addition to task-relevant ability and knowledge, subordinate needs and personality also moderate the desire for highly structured work and the effectiveness of close supervision. Subordinates high in both independence and a need for challenge are likely to respond less positively to close supervision regardless of the task. An essential element of the Hersey-Blanchard model is not only the direction of subordinates, but their personal development as well. Coaching and guidance become more important than direct targeted supervision as the subordinate becomes more capable. Increasing subordinate participation in the definition of objectives and the setting of goals shifts the subordinate from extrinsic motivation to an intrinsically focused, self-regulation.

References

- Blackwell, Ch. W. Gibson, J.W. (1998). A Conversation with Leadership Guru, Paul Hersey. Journal of Leadership Studies 5 (2), 143.

- Einstein, W.O., Humphreys, J.H. (2001). Transforming Leadership: Matching Diagnostics to Leader Behaviors. Journal of Leadership Studies 8 (1), 48.

- Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Leadership. (2007). Web.

- Hersey, P., and Blanchard, K. H. (1977). Management of organizational behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Hersey, P., and Blanchard K. H., & Hambleton R. K. (1980). “Contracting for leadership style: A process and instrumentation for building effective work relationships”. In P. Hersey, and J. Stinson (Eds.), Perspectives in leader effctiveness (pp. 95-120). Athens, OH: The Center for Leadership Studies.

- Lagone, C. A., and Rohs, F. R. (2003). Community Leadership Development: Process and Practice. Journal of the Community Development Society, 26 (4), 252-267

- Mabey, C., Salaman, G. (2003) Strategic Human Resource Management, Blackwell Business, Oxford.

- Price, A. (2004). Human Resource Management in a Business Context, 2nd edition. Thomson Learning.

- Polleys, M.S. (2002). One University’s Response to the Anti-Leadership Vaccine: Developing Servant Leaders. Journal of Leadership Studies 8 (3), 117.

- Segriovanni, Th., Glickman, K. (2006) Rethinking Leadership: A Collection of Articles. Corwin Press; 2nd edition.

- Situational Leadership (2007).

- Sogunro, O.A. (1998). Leadership Effectiveness and Personality Characteristics of Group Members. Journal of Leadership Studies 5 (3), 26.

- Stirling, J.B. (1998). The Role of Leadership in Condominium and Homeowner Associations.. Journal of Leadership Studies 5 (1), 148.

Appendix