Introduction

The concept of comparative advantage is central to the international trade discourses that are driven by perspectives of competitive advantage. In a bid to place organisations’ goods and services in the global market, price is an important factor that enhances the competitive advantage of an organisation in comparison with other organisations that offer similar goods and services in the global market.

Offering goods and services at a low price implies the capacity to produce goods and services at low costs. Alternatively, it suggests that a nation or even an organisation that has the capacity to place goods and services in the global market at low prices has a competitive advantage in the production of the goods and services in comparison with other nations or organisations (Deardorff 2005). A major question that emerges when evaluating the theory of comparative advantage from an economist context is whether two nations, which are good at producing two commodities, should engage in trading in the same commodities. In the attempt to respond to this interrogative, this paper evaluates successfulness of the theory of comparative advantage.

Definition and Illustration of the Theory of Comparative Advantage

Different nations produce goods and services at different efficiency levels.While two nations may have the capacity to produce two different types of goods; each of them may be established to produce one of the types of goods at a higher pace in relation to the other. The theory of comparative advantage advocates that nations or even firms should consider producing goods and services, which they are effective and efficient at producing. This suggests that they should be willing to incur an opportunity cost for goods and services they are not effective at producing.

From the above assertion, since such goods are required in the economy, nations should consider buying them from nations, which are more efficient in their production. This strategy is the underlining principle for the theory of comparative advantage. Deardorff (2005, p. 1005) defines comparative advantage as ‘the ability of a party to produce a particular good or service at a lower marginal and opportunity cost over another’. Opportunity cost involves the service or the good that a nation or an organisation sacrifices in the quest to produce the good or service it is more efficient in its production.

To illustrate the theory of comparative advantage, supposing hypothetically, England has the capability of producing leather shoes at the rate of 200 pairs per hour and the capacity to produce shirts at 125 pieces per hour. Supposing also China has the ability to produce similar shoes at the rate of 150 per hour and similar shirts at the rate of 300 pieces per hour. Table 1 below shows the opportunity costs in these two nations when they decide to produce products that they are well positioned to produce efficiently. From the table, it is evident that if the cost of importation is lower than the cost of low production efficiency, the two nations can gain from trading with one another.

Table 1: Opportunity Cost and the Concept of Comparative Advantage.

Successfulness of the Theory of Comparative Advantage

Adams Smith first developed the concept of comparative advantage in his book Wealth of Nations. Aiginger (2006, p. 64) quotes Adam Smith’s assertion, ‘if a foreign country can supply us with a commodity that is cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it from them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage’. However, David Ricardo formally postulated the theory in his book titled On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in which he compared the relative costs of producing wine and cloth in both Portugal and England (Samuelson & Heckscher 1999).

In his analysis, David Ricardo deduced that Portugal could produce both cloth and wine at very low labour costs in relation to the production of similar quantities in England. Nevertheless, there was consistency in the rate of manufacture of the two commodities in the two nations. England found it simple manufacturing cloth, but extremely hard to make wine. Although Portugal could produce the two items with ease, the cost of producing excess wine was far low than producing cloth (Samuelson & Heckscher 1999).

David Ricardo concluded that Portugal should produce wine and buy cloth from England and vice versa for England. This conclusion suggested that comparative advantage exists even if one nation may be having absolute advantage in the event that relative efficiencies in the production ability exist between two nations (Deardorff.2005). In such a situation, comparative advantage is successful in reducing the costs for running an economy.

The theory of comparative advantage postulates that nations need to specialise in producing products they have higher relative efficiencies for their production. Consequently, the theory of comparative advantage is successful since, ‘despite the absolute cost disadvantages in the production of goods and services, a country can still export those goods and services in which its absolute disadvantages are the smallest and import products with the largest absolute disadvantage’ (Krugman & Obstfeld 2003, p.55).

By deploying the theory, nations that have absolute advantages in terms of low cost of products can specialise and export the products that have the highest cost advantage as populated by David Ricardo. In this context, comparative advantage leads to specialisation in terms of the absolute advantage that nations possess. However, the theory is unsuccessful in that it compels nations to import no matter whether they are more efficient in the overall production of all goods and services compared to other nations.

Specialisation in the production of goods and services that a nation has a relatively higher comparative advantage is important for success in terms of cutting the cost of running an economy. However, Schott (2004) cites confusion in the theory on the grounds of the capacity of a nation, which is less efficient in the production of all types of goods and services to export into nations that have higher absolute comparative advantage.

Krugman (1993) provides a possible response to this interrogative, which validates the successfulness of comparative analysis theory through the self-equilibrating trait for international trade. According to this principle with reference to Salvatore’s (2002, p. 48) line of thought, ‘if the input cost is sufficiently lower in one country than another country, the price of the product will be lower in the low input cost country, even if that country is less efficient in the production of the product’. This suggests that misalignment in equilibrium of trade compels exchange rate alignments so that a new equilibrium in trade emerges.

When the successfulness of the comparative advantage theory is evaluated as David Ricardo postulated the theory, it is unsuccessful. Ricardo principally based his arguments on labour cost suggesting that labour was the only crucial factor considered in the determination of efficiency of production of goods and services. Root (2001) supports this criticism by adding that the theory never considered non-homogeneousness of labour. In fact, according to Deardorff (2005), this weakness prompted the incorporation of perspectives of opportunity costs in a bid to make the theory more successful in providing valid explanations on why nations should engage in trade, notwithstanding the capacity to produce multiple goods and services. Upon restructuring the comparative advantage hypothesis in the context of opportunity price tag, it means that a nation has a relative benefit if a commodity or a service is produced while incurring the lowest chance rate in comparison with other nations.

Amid the claims raised above on the unsuccessfulness of comparative advantage theory, its impacts on helping nations gain from trading with one another cannot be invalidated (Krugman 1990). Indeed, international trade organisations squarely rest their principles on validation of comparative advantage theory (Root 2001). Research also shows that relaxing various assumptions made in the development of the theory fails significantly to influence its success (Bernhofen & Brown 2004; Schott 2004). Additionally, research by Uchida and Cook (2005), Krugman, and Obstfeld (2003) provide empirical evidence on the success of the theory.

Salvatore (2002) summarises the successfulness of the theory claiming that its impeccable success rests on the important information it avails. This information includes ‘conditions of production, the autarky point of production and consumption, the equilibrium relative commodity prices in the absence of trade, and the comparative advantage of each nation’ (Salvatore 2002, p. 91). As claimed before, comparative advantage theory also provides information on trade volumes and trade terms.

Amid the success of the theory of comparative advantage, it does not go without criticism. Chang (2002) claims that the theory played roles in ensuring that the developed nations maintained their leadership in selling value-added products to the developing nations. Thirlwall (2006) claims, ‘major developed countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom used interventionist and protectionist economic policies in order to get rich and then try to forbid other countries from doing the same’ (p.97). This assertion is supported by the fact that developed nations are technologically developed than developing nations, which are relatively better in agriculture (Chang 2008).

Comparative advantage theory calls developing nations to continue purchasing expensive technological products from the developed nations while the developed nations continue purchasing cheap agricultural raw materials for value addition and then re-sale the valued added products to the developing nations. Such a situation ensures that developing nations never advance technologically and/or will never develop the capacity to add value to locally produced agricultural products. Indeed, according to Chang (2002), China and Japan utilised protectionist policies to enhance their economic development. By focusing on comparative advantage in the production of manufactured and value added products, China has emerged as another global economic super power nation.

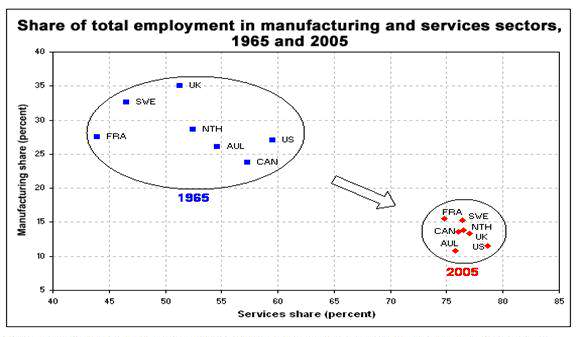

The successfulness of comparative advantage theory is incomplete without consideration of how it applies to major world economies. Graph 1 below shows how the theory applies in the US manufacturing and service sector with the onset of higher economic growth in China due to increase manufacturing comparative advantage.

China’ comparative advantage currently rests on the manufacturing capability through labour intensive approaches. However, according to Deardorff (2005), work-exhaustive businesses appear in China’s relative benefit, but usual resource-rigorous businesses, investment-exhaustive industries, and IT-thorough companies are in China’s relative benefit. China has a huge availability of educated and skilled labour supply. According to the US Bureau of Labour Statistics (2007, p. 19), ‘in 2007, reimbursement expenses in relation to the United States in Mexico and the Philippines were 13 percent and 4 percent of the U.S. level, respectively’. In 2006, Chinas’ labour cost comparison statistics indicated that its labour was 2.7 percent of the labour cost in the US manufacturing sector. This explains higher comparative advantage of China in manufacturing while the comparative advantage of the US is shifting towards the service sector, mainly the provision of professional services as shown in graph 1.

Conclusion

Some countries are better in terms of production of certain products and services. Hence, it is natural that international trade should exist so that different nations can benefit from the production abilities of other nations instead of investing in inefficient production processes. Based on this assertion, the paper revealed that comparative advantage is a successful theory that helps to shape international trade principles. However, it was also claimed that the application of theory might enhance more growth of some economies in relation to others. Such a case applies especially where comparative advantages in developing nations are on the production of cheap non-value-added agricultural commodities. Nevertheless, amid this criticism, there is empirical evidence documenting the success of comparative advantage theory in fostering the progress of nations through specialisation and protecting of economics from encountering unnecessary costs.

References

Aiginger, K 2006, ‘Competitiveness: from a dangerous obsession to welfare creating ability with positive externalities’, Journal of Industrial Trade and Competition, vol. 6 no. 5, pp. 63-66. Web.

Bernhofen, D & Brown, J 2004, ‘A direct test of the theory of comparative advantage: the case of Japan’, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 112 no. 1, pp. 48-67. Web.

Chang, H 2002, Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective, Anthem Press, London. Web.

Chang, H 2008, Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism, Bloomsbury Press, London. Web.

Deardorff, A 2005, ‘How Robust is Comparative Advantage’, Review of International Economics, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1004–1016. Web.

Krugman, P & Obstfeld, M 2003, International Economics: Theory and Policy, HarperCollins, New York, NY. Web.

Krugman, P 1990, Rethinking International Trade, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web.

Krugman, P 1993, ‘What do undergrads need to know about trade?’, American Economic Review, vol. 83 no. 2, pp. 23-31. Web.

Root, F 2001, Entry Strategies for International Markets, Lexington, MA, Lexington Books. Web.

Salvatore, D 2002, International Economics, Macmillan, New York, NY. Web.

Samuelson, P & Heckscher, O 1999, ‘Trade Theory with a Continuum of Goods’, Quarterly Journal of Economics , vol. 95 no. 2, pp. 203-224. Web.

Schott, K 2004, ‘Across-product versus within-product specialisation in international trade’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 119 no. 2, pp. 641-457. Web.

Thirlwall, A 2006, Growth and Development With Special Reference to Developing Economies, Palgrave, New York, NY. Web.

Uchida, Y & Cook, P 2005, ‘The transformation of competitive advantage in East Asia: an analysis of technological and trade specialisation’, World Development, vol. 33 no. 5, pp. 701-728. Web.

US Bureau of Labour Statistics 2007, International Comparisons of Hourly Compensation Costs in Manufacturing, US Bureau of Labour Statistics, New York, NY. Web.