Introduction

It is becoming significantly imperative to understand the operations of multinational enterprises due to globalization of business. While there is no conventional agreement for the term globalization, in economics, it is used to refer to international integration in commodity and labor markets (Bordo et al.2003, p.187). There have been at least two episodes of globalization since the mid 19th century if international integration is taken as a base for the markets according to Baldwin and Martin (1999, p.19). In a global scale, effectiveness of these corporations can be critically determined by the kind of human resource management systems that they put in place. These systems starts a check right from the type of people who are recruited into the multinationals and the appraisal methods during their tenure all through their entire time with the companies. When fresh graduates leave colleges and universities after years of academic work culminating into joyful reward of being holders of degrees or diplomas, many of them end up seeking for jobs in various institutions. During hiring; employers look for the best the market can offer them so as to maintain a degree of quality in their operations (Richbell, 2001, p. 276). The result is vigorous recruitment processes that try to determine the best of the applicant(s) suitable to be absorbed. Personality a major component of theses interviews is the set of more stable and enduring traits of a person that uniquely differentiates them with others, but allows for comparison between them to be made (Ogden 3). The management of these people has a direct bearing on the performance of the companies they work for. In most cases it is how their appraisals are conducted that determine their usefulness to the firm. Although there are various methods of employee appraisal system structures, there is no clear distinction on the best method to be used. In the case of dmg world media, the HR driven performance management and the open exchange method are being concurrently used. There is no decision of which single method is the best way of performance management or conduct appraisals.

Current globalization of human resource management trend

The basic components of international human resources management concern staffing, management training and development, performance appraisals, and compensation policies. Cultural difference is a major factor that has to be dealt with when global human resources management is involved (Bordo, Taylor & Williamson, 2003, p. 85). These cultural differences vary from country to country depending on several factors. These lead to corresponding human resource practices. A country’s culture entails certain values and symbols which the locals interpret in particular ways. The beliefs language and norms that outline the behavioral pattern is also different. A particular learned behavior develops in an individual as a person grows up in a particular place from childhood to adulthood and is taken into account when dealing with the individual (Dalton, 1998, p. 109). In order for a multinational to do business in another country other than where they operate, they need to learn the work culture of those particular countries and adjust accordingly ( ). For instance, most people in the west work from Monday to Friday with Saturday and Sunday being a weekend. In the Middle East the working days are from Sunday to Thursday with the weekend being on Friday and Saturday. This not only requires the companies to adjust to a different working cultures but also communication times and days.

Management training and development

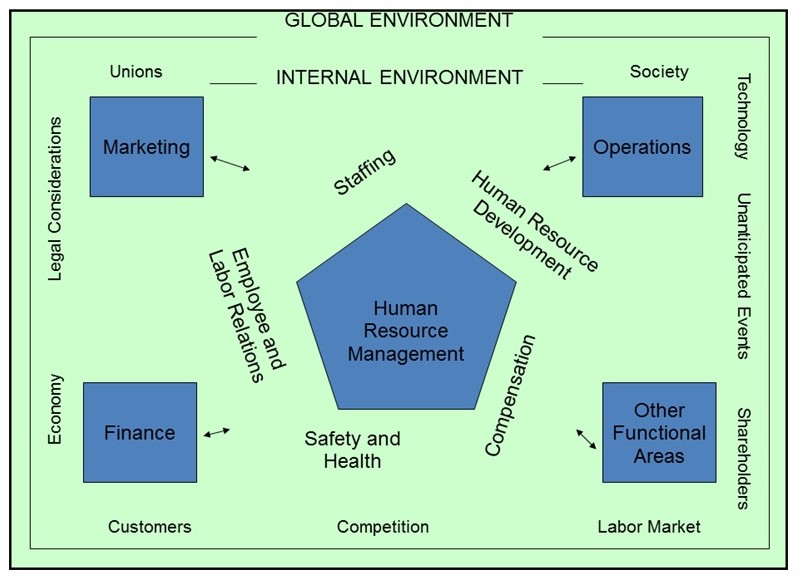

Professional approach to human resources management involves several aspects that are addressed differently in various places. Strategic international human resources management is one bit that has picked up through out the world. To some extend, services such as recruitment are outsourced from consulting firms which also multitask (Mayer & Davis, 1999, p 167). The consulting firms like Pricewaterhousecopers, and Deloitte perform are range of duties such as assurance, recruitments, auditing, financial advisory among others business related services. As pertains human resources management, they perform a variety of tasks like restructuring of entire organizations, and appraisals apart from recruitment. In cases where this is internally done then global HR managers are obligated to undertake the aforementioned duties. They develop and operate integrated global human resources management systems that have resemblance to the smaller scaled domestic systems. Their focus is on organizational effectiveness and employee development that is achieved only by efficient running of the system. The system is neither run vertically nor horizontally but as a mixture of both. A typical system may look as shown in the diagram below.

Staffing

Every organization tries to equip itself with the best staff possible. This however is challenging issue in both local and international organization. Global staffing is another sensitive aspect of global human resources management that a company needs to be well versed with its logistics for multinationals (Pucik, 1996, p. 76). For multinationals, employees may be expatriates, host-country nationals, or third-county national. The first are employees who are not citizens of the country the company is located but are nationals of the country in which the company has it’s headquarter. Host-nation nationals are employees who are citizens of the same nation that the particular subsidiary is located. There are also employees working in a second country that is neither their country nor the headquarters of a particular organization (Becker & Gerhart, 1996, p.786). Significant background investigations may be done for each of the cases above to before the employees are hired a move that may easily be overlooked in nationally based industries. Normally differences across cultures and countries are barriers to overcome. Employees such as expatriates may find difficulty in adjusting to the new environment, or are finally completely unable to do so. Reasons such as the physical conditions like temperatures, religion or foods contribute to the barriers. For the company, a particular country’s laws especially those related to tax, customs and procedures for background screening are some of the issue that have to put up with. The environment in a country should be evaluated before setting a business in a foreign country. In the event a company is unable cope with the above, it may close up its operations in that particular place. A common case is where the parent company opened a subsidiary in a certain country when the laws were favorable then the laws are change in a manner that no longer favors their operations in that place. In such a case an organization many not be able to perform effectively leading competitive disadvantage.

Staffing currently takes three generalized forms: ethnocentric, polycentric, and geocentric (Storey, 2001, p. 43). In ethnocentric, strategic management positions are all field by nationals of the parent country of the company. This solves any problem of qualified managers in host country, unifies the corporate culture, and leads to transferring of core competencies. On the down side, the policies normally produce resentments in the host country and sometimes lead to cultural myopia. The resentment is caused by the limited job advancement opportunities for the host country nationals and lowers productivity of a company (Roberts, Ellen E. & Ozeki, 1998, p 96). It also increases the rate of human resource turn over. The cultural myopia leads to failure in understanding of the host country’s culture and the differences with the parent country. A good understanding is necessary for management and marketing of the company. In the second case, the subsidiaries are managed by the host country nationals while key headquarter positions are left for nationals of the parent country. Multi-domestic businesses are best suited by this kind of arrangement. It not only helps to alleviate myopia, but also cheap to implement and helps in transferring the core competencies (Schuler, 1990, p. 213). It though limits the host country’s nationals experience to only within their country and generates gaps between the operations of the host country and the parent country (Laurent, 2006, p. 97; Cherrington, Reitz & Scott, 1997, p. 589). Management transfer also lacks within the company structure leading to lack of integration. It is difficult to experience curve and location economies. Geocentric policy seeks the best suitable candidates for management positions regardless of their nationality. The policy best suits global and trans-national businesses world wide. It allows the companies to maximize the use of their human resources (Jackson & Schuler, 1995, p. 276). Managers also get equipped to work in a number of cultures. There is also the building up of strong unifying culture and informal management networks that ease company operations (Jackson & Schuler, 1995, p 275). The policy reduces cultural myopia and creates value from location economies. Implementation of the policy is sometimes limited by national immigration laws. The training and relocation of staff makes the system expensive. Compensation structures are also complex, expensive, and sometimes even problematic.

To reduce the kind of above incidences, preventive measures are taken in advance. For example, prior to departure, the foreign employees are oriented and trained in the challenges they may meet ahead in their new job placements (Conger, FineGold & Lawler, 1998, p. 653). Areas considered in clued among others: language, culture, history, local customs, and the living conditions in the host nation. During their assignments, they are helped to continue expanding skills, career planning, together with home-country development. The lifestyle, workplace conditions and employees of destination are pre-mentioned in their briefing. The below figure, provides a general view of such a preparation.

Compensation policy

Compensation of host country nationals for multinationals that are venturing into a new market is a matter that the human resource managers keenly look at prior to the company’s operations. Organizations think globally and but acts locally in issues of this kind (Dutton, 1999, p.68). The remuneration rates awarded are normally slightly above the prevailing wage rates in the given country. Variation s in tax, living standards, and other factors that affect particular employees are all considered in the package that they do take home. This is the reason why most multinationals are the best payers in the job market in any region of the world. They therefore attract some of the best employees the market has to offer which consequently help in their operational performance. The factors considered are normally the minimum wage that differs in various parts of a country from the big cities to the small counties (Otley, 2002, p 237; Bloom & Milkovich, 1998, p 275). The working times in that country which include: annual holidays, the time of the month for pay, paid personal days, times for vacation, the weekly working hours, allowed probation periods. Restrictions on overtime and payments, hiring and termination rules, and regulations covering several practices like medical cover and retirements benefits (Laabs, 1998, p. 13). Culture plays significant roles in determining the remuneration guidelines for employees in different parts of the world. In North America, emphasis is made on individualism and high performance, and compensation practices are tuned to encourage along this lines. The Europeans stress on social responsibility and the Japanese tradition is to priorities age and company service as the basic determinants of compensation (Barton, & Bishko, 1998, p. 67-69).

Most expatriate compensation cost between three to five times host-country salaries per annum. This varies depending on the foreign exchange rates favorability. The costs do include: overall remuneration, housing, cost-of-living allowances and physical relocation which typically applies to most expatriates. In this category of employees, the country of origin/ culture determines the cost of compensation (Ashamalla, 1998, p. 61). People of United States origin command a higher pay relative to those from other parts of the world. In Europe and Asia, people shun conspicuous wealth and Italians value teamwork more than individual initiatives. The pay cheques therefore vary for all the above.

Expatriates fail to successfully perform the in their duties in most cases due to several reason. These vary mainly for various nationals. For individuals from the United States it is mainly the inability of the spouse, family members or the manager to adjust or family problems. The managers may have personal or emotional immaturity that affects their work away from home (Duane, & Hitt, 1990, p 52). In most cases, the oversee responsibilities involve a promotion from the domestic position held prior to the posting. For the Europeans, it is the inability of the spouse to adjust that mainly leads to their failure to perform. The Japanese too do find it difficult to adjust to the larger oversee responsibilities and face difficulties with new environments (Kopp, 2006, p. 589). They experience personal and emotional problems easily. Technical competence may also another problem that the Japanese may face. Like the British, inability of spouse to adjust to the new environment may lead to their failure in their performance.

Appraisal

The manners in which appraisals are conducted determine the method of management in the system. Appraisals are normally aimed at reviewing the performance and potential of employees, and are sometimes linked to a reward review. They enhance performance of both employers and employees by identifying their strengths and weaknesses (Wood, 2003, p. 356). This enables determination of which areas they are best suitable to improve in. While it is not a legal requirement to introduce appraisal schemes, legislation is in place to accommodate its usage (Welch, D. 2007, p.275).

In determining any performance management (PM) system, written records should be made key component of the PM. These allow the top management to monitor the effectiveness of the PM and a feedback to employees. Focus is made on employees work performance and not personal character through the help of job description (Poole, 1990, p. 213). Several techniques are used in traditional HR-driven performance management which includes:

- Comparison with objectives – The managers or employers come together and agree on a set(s) of objectives that need to be attained as individuals or the group as a whole. Measurement of performance is then based on the degree by which the objectives have been met.

- Critical incidents – Under this method of appraisal, records are made of crucial negative or positive incidents that happened to the employee within the stipulated time of the assessment.

- Narrative report – The performance of the employee is simply described in detail by the assessors in their own words.

- Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales– These are a combination of rating scales that are customized for varied job positions each having its way on the road.

Procedures against assessment ratings should be put in place. This is significant in allowing for appeals again.

Overcoming appraisal performance management

Senior managers apart from the immediate junior supervisors should be allowed to participate in the appraising of employees. This reduces some of the inconsistencies that arise from performance appraisals (Huselid, 1997, p 186). The monitoring and coordination of the performance management system should also be done by a senior manager. Through the entire reporting period, management need to keep updated running records of the employees’ performance in order to made music out of it. Inconsistencies in reporting standards should be reduced by provision of suitable training to the assessors before they conduct the service

Reward reviews

These are incentives awarded by employers to employees on the basis of employee performance in the appraisals (Kerr & Slocum, 1987, p 98). Normally this takes the form of bonuses, salary increment among others. Generally there is usually a link between the appraisal system and the reward review though it is preferable that these take place at different times (Murphy, & Jensenand, 2001, p. 87). As a precaution, employers should carefully examine their financial arrangements before venturing in such projects due to the vast sums of cash involved. Consultations should not only take place with the managers but also with the junior employees and the trade unions so that amicable agreements are arrived at before such schemes are implemented to enhance harmony among stakeholder (Shuler, Dowling & De Cieri, 1993, p 736).

Performance management at world media (Open exchange)

The system although only slightly, is different works like with moon. That is with brightness than can only be brought about by the company. The company leaves individuals who are well equated to perform their duties within the same district. The system leaves the person feeling as if they need to talker but focuses oh his orientation which is line here, and leave. The individual in question possess high a very high degree of self well being, confidence and the receipt of well organised in their work. If expatriated, the employees will be in a position to themselves drive actually. To bridge award together is not very more of an opinion than a political gesture that id May. Kindly gets may. The system allows to each, acceptance, there are individual works efforts that employees make to help in building the entire effectiveness of the system. Its open nature makes employees ability to develop relationships with their fellow employer and other employees. Willingness to communicate is developed by employee since they know that their bosses will listen to them and get interested in helping them achieve their goals (Aaker & Joachimsthaler, 1999, p 189). When the employees meet these targets, the company gains more revenue. In the conventional system of HR management, policies such as ethnocentric and polycentric forms of education result in communication breakdown which has negative several negative repercussions. The perceptual ability of employees in multinational environment of the method enables employees develops the ability of knowing how another country or a particular people have a certain behavioral pattern (Storey, 2001, p. 38). These abilities reduce cultural myopia in the office and enhance good management and marketing of the company due to better understanding of the population it operates on. The supervisors and senior managers in the open exchange system of dmj are non judgmental and flexible in management styles. This allows for freedom of expression operation by individuals in the work place which is healthy for good growth (Bloom & Milkovich, 1998, p 271). Problems are easy to identify in such as surrounding and solved. When this is done running of multinationals even on larger on global case becomes a walk in the park. The idea of correcting mistakes there and then together with the supervisor in the open exchange method of appraisal helps in avoiding repeat of the same mistake. This is better than the current conventional method that waits for normally an entire year to evaluate performance. In the event employee make mistakes, they are likely to repeat it especially in a recurring activity since it hasn’t been corrected. The relation between, country and expatriates assignments adjustments are easy to achieve through the dmj method. This is due cultural toughness that is associated that cements the relations within the work place.

Conclusion

Human resource management practices are great determinant of an organization performance. As the most important resources in an organization, human resource management should ensure the resources contribute positively to the organization. Human resource management in global environment is made more challenging by the various diverse considerations that should be considered. Performance management is a very important aspect of human resource management. Performance management ensures that there is consistent performance in an organization. As an international company, dmg World Media should ensure that its performance management enables consistent high performance throughout the organization. This calls for a performance management that is effective in all branches despite of their cultural diversity. The ‘Open Exchange’ performance management and a strong organization culture can help improve performance and gain competitive advantage in the global business environment. The ‘Open Exchange’ enables quicker evaluation of employee and timely corrective measure to be taken. Despite of the benefits of the system, the dmg Global Media should be aware of the negative effect. The system can open doors for victimization of some employee leading to counterproductive effects.

Reference

Aaker, D. & Joachimsthaler, E. 1999.”The lure of global branding”. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 77, No. 6, pp.137-144.

Ashamalla, H.1998.” International human resource management practices: The challenge of expatriation”. Competitiveness Review, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 54-65.

Baldwin, R. & Martin, P., 1999, Globalization: a new phenomenon. London: Edward Elgar.

Barton, R. & Bishko, M.1998. ”Global mobility strategy”. HR Focus, Vol. 75, No. 3.

Becker, B. & Gerhart, B. 1996. “The Impact of Human Resource Management on organizational Performance: Progress and Prospects”. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 779-801.

Bloom, M. & Milkovich, G. 1998. A SHRM Perspective on International Compensation and Reward Systems. CAHRS Working Paper Series. Web.

Bordo, M. Taylor, M. & Williamson, J., 2003,”Globalization in historical perspective”. London: University of Chicago Press.

Cherrington, D. Reitz, H. & Scott, E. 1997. Effects of contingent and noncontingent reward on the relationship between satisfaction and task performance. Journal of applied Psychology, Vol. 55, No. 6, pp. 531-536.

Conger, J. FineGold, D. & Lawler, E. 1998.”Appraising Boardroom Performance”. Harvard Business Review.

Dalton, G.1998.”Global challenges”. Informationweek, (700), 19ER-20ER.

Duane, R. & Hitt, A.1999. “Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership”. The Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 13, No.1, pp. 43-57.

Dutton, G.1999. “Building a Global Brain”. Management Review, pp34-38

Huselid, M. 1997. Technical and strategic Human Resource Management Effectiveness as Deterninant of Firm Performance. Academic of Management Journal. Vol.40, No. 1, pp. 171-188.

Jackson, S. & Schuler, R. 1995. “Understanding Human Resource Management in the Context of Organizations and their Environments. Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 46, pp. 237-264.

Kerr, J. & Slocum, J. 1987.” Managing Corporate Culture through Reward Systems”. Academic of Management Executive, Vol 1, No. 2, pp. 99-108.

Kopp, R. 2006. “International human resource policies and practices in Japanese, European, and united states multinationals”. Human Resource management, Vol. 33, No, 4, pp 581-599.

Laabs, J. 1998. “Getting ahead by going abroad”. Workforce, Vol. 3, No.1, pp.10-11.

Laurent, A. 2006. “The Cross-Cultural Puzzle of International Human Resource Management”. Human Resource Management, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 91-102.

Mayer, R. & Davis, J. 1999. “The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment”. Journal of applied Psychology, Vol. 84, No. 1, pp.123 136

Murphy, K. & Jensenand, M. 2001. “Performance Pay and Top Management Incentives”. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98. No. 2.

Ogden, C. K., 1926. Personality. London: Routledge.

Otley, D. 2002. “Performance management: a framework for management control systems research”. Management Accounting Research, Vol 10, No. 4, pp. 363-382.

Poole, M. 1990. “Editorial: Human resource management in an international perspective” The international Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp 1-15.

Pucik, V.1996.” Human Resources in the future: An Obstacle of a champion of Globalization?” CAHRS Working Paper Series. Web.

Richbell, S. 2001. “Trends and emerging values in human resource management.” International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 22, No. 22, pp 261-268.

Roberts, K. Ellen E. & Ozeki, C. 1998. “Managing the global workforce: Challenges and strategies”. Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp 93-106.

Schuler, R. 1990. “Repositioning the Human resource Function: Transforming or Demise?” Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 4, No. 3.

Shuler, R. Dowling, P. & De Cieri, H. 1993. “An Integrated Framework of Strategic Intentional Human Resource Management”. International Journal of Human Resource management, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 717-764.

Storey, J., 2001, Human resource management: a critical text. New York: Routledge.

Welch, D. 2007. “Determinants of International Human Resource Management Approaches and Activities: A Suggested Framework”. Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2. pp.139-164.

Wood, S. 2003. “Human Resource management and performance”. International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp 367-413.