Introduction

There are multiple definitions of leadership, with each elucidation emphasizing different aspects of leadership. Some consider leadership an act or conduct, while others consider it a group management process or art of inducing submission. In this view, several theories have been established to describe and analyze leadership’s nature from various perspectives. There are three major approaches to studying leadership: situational, behavioral, and trait. This paper synthesizes the literature on theories that describe the nature and exercise of leadership from this perspective.

This writing piece’s first section contains a detailed assessment of leadership theories from three perspectives. The second part presents a critical evaluation of the deportments of leaders encountered throughout my career; it includes an in-depth evaluation of their behavior, per the theories discussed in the first section. Finally, the paper provides a reflective analysis of learned concepts and strategies to improve my leadership capacity. Because leadership is crucial in directing management practices in an organization, managers must understand what makes leadership effective. The theories discussed in this paper will reveal the secrets of effective leadership.

Key Theories of the Nature and Exercise of Leadership in Organizations

Trait Approach

The trait approach is grounded on the great man theory, which asserts that some individuals are born with the right attributes or traits to become leaders. It is one of the earliest leadership theories; it focuses on influential leaders’ qualities, including physical appearances, personality (dominance, aggressiveness, and self-confidence), intellective (knowledge, judgment, and decisiveness), social characteristics, and task-related features (Bright et al., 2019). A manager’s attributes can be determined by their least-preferred coworker (LPC) or the person they are least inclined to work with within the workplace. It is assumed that the LPC score can reveal an individual’s underlying traits towards others (Bright et al., 2019). A leader with a high LPC score is relationship-oriented, the one with a low LPC score is task-oriented, and one with a middle-range LPC score can be effective in a wide situation range.

The trait approach assumes that the enlisted traits increase a leader’s likelihood of success and effectiveness. According to Ralph Stogdill, the pioneer of the trait approach leadership, an effective leader must possess at least the following traits (Bright et al., 2019):

- Drive- A strong desire or ambition to achieve goals.

- Self-confidence and assurance in ideas, strategies, decisions, etc.

- High tolerance for stress and other stressors.

- Knowledge or expertise in the area of interest.

- Honesty and integrity.

- Willingness to take responsibility for decisions and actions.

- High cognitive ability- skilled in making strategic decisions and good judgment.

- Desirable personality- charisma, creativity, adaptive/flexibility, and friendliness.

The Big Five personality framework is also one of the most common personality theories. It groups personality traits into five groups: extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism (Northouse, 2019). Extraversion refers to one’s tendency to be hostile or emotionally vulnerable. Openness relates to a leader’s creativity and curiosity, and agreeableness is the leader’s ability to accept, nurture, and create a trusting environment. Conscientiousness refers to one’s ability to be organized, dependable, organized, and in control.

The personality trait theories received widespread criticism for their construct weakness. Psychologists argue that success in leadership takes more than just possessing the right traits. A leader requires skills, ability, vision, and strategy, among other things, to be successful. Walter Mischel, a psychologist, points out that personality traits are expressed during ‘weak situations’ and suppressed during ‘strong situations’ through conduct (Northouse, 2019). A typical workplace or social system does not have a continually weak or strong moment; instead, they tend to fluctuate from one situation to another. Simply put, a leader with certain traits will be effective in some cases but not in others.

Another crucial weakness of the trait approach is that there is no evidence to support the idea that leaders are born. A person is not born with self-confidence or knowledge; they develop it (Bright et al., 2019). On the other hand, honesty and integrity are matters of individual choice, not in-born traits. Although cognitive ability has a genetic predisposition, it also still needs to be learned. For these reasons, the trait approach fell out of favor in organizational psychology.

However, recently, there has been renewed interest in the trait approach following Barack Obama’s disputed leadership success. Obama’s success as a leader was ascribed to his charisma, among other characteristics (Northouse, 2019). According to a past study, there was a link between charismatic leaders’ traits and success (Northouse, 2019). Despite its shortcomings, the trait approach provides direction on what features are essential in leadership. Leaders can use this information to understand who they are and how they can improve themselves to the company’s benefit. People with the right traits are more likely to succeed as leaders than those without these traits.

Situational Approach

An important concept that emerged from early leadership literature is that traits account for only a fraction of a leader’s effectiveness. There are other factors, including situations, that influence leadership success and efficacy. For example, certain behaviors can generate positive outcomes in one circumstance and the opposite effect in a different case. This observation led researchers to explore when and why one trait would produce differing results.

Several theories, including Fielder’s contingency theory, decision process theory, path-goal theory, cognitive resource theory, decision tree model, and Hersey and Blanchard’s life cycle theory, have been developed to address this issue. Retrieved findings highlighted that key contingencies and situational differences play a critical role in influencing a leader’s success. This paper will focus on Fielder’s contingency theory, Path-Goal theory, and Vroom’s Expectancy Theory.

Fielder’s Contingency Theory

The contingency theory posits that a leader’s success depends on how well their style fits the situation or setting. Fielder developed this theory by studying a leader’s administrative framework, the context in which it was applied, and whether it was adequate (Vidal et al., 2017). He concluded that some situations would favor a manager’s style, and others will not. Factors influencing the appropriate nature of a leader’s environment include leader-follower relationship, task structure, and position power. The leader-follower relationship is characterized by a follower’s acceptance and loyalty to the leader (Huang et al., 2015). Task structure refers to how well a given task has been detailed and how clear its goal and achievement method are. Position power refers to the leader’s ability to influence his group.

A high-LPC (relation-oriented) leader is more effective in situations with intermediate situation favorability. Low-LPC (task-oriented leaders) is very effective in highly favorable and unfriendly situations (Vidal et al., 2017). They allow their team to perform tasks without imposing directive behavior. Under suitable conditions, the task-oriented leader sets goals, details work methods and guides the team towards achieving the task goals. Leaders with middle-range LPC scores are the most influential leaders (Bright et al., 2019). They can be task-oriented to accomplish goals but, at the same time, show consideration for team members.

Path-Goal Theory

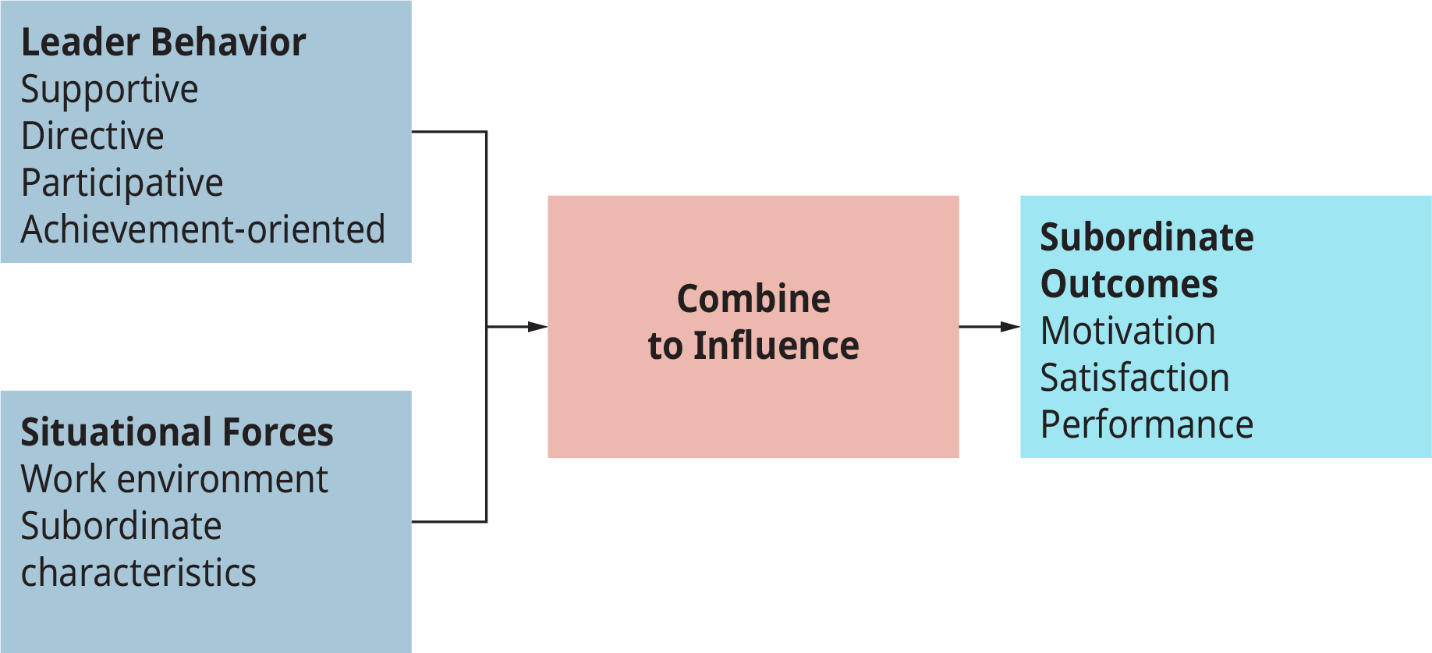

The path-goal theory analyzes how leaders can motivate their followers to achieve goals. The theory recognizes the leader-follower relationship in attaining the organizational goal (Bright et al., 2019). The major components of the postulation include a leader’s behaviors, followers’ conduct, task characteristics, and motivation. It posits that a manager’s deportment influences followers’ behavior and task characteristics, which, in turn, influence follower motivation. (See figure 1).

The following section explains the three major components of the path-goal theory: leaders’ behaviors, followers’ deportment and task characteristics, and motivation.

Leader Behaviors

A leader’s conduct can be directive, supportive, participative, or achievement-oriented. Directive behaviors help team members to achieve goals by providing direction. The leader establishes goals, strategies, and procedural rules, sets timelines, defines roles and performance standards, and shows the followers how the objectives will be achieved. Directive conducts are a one-way street- the leader communicates what needs to be done, how it will be executed, and who will be responsible for the task. It clarifies when task ambiguity is high, allowing followers to focus on their jobs and improve job productivity.

In contrast, supportive behavior involves two-way communication to show emotional support to followers. Supportive conducts are beneficial in situations where tasks are boring, stressful, unpleasant, and tedious (Bright et al., 2019). By being supportive, the leader builds their followers’ confidence and determination in facing a task. Participative leadership involves requesting feedback from staff and shared decision-making. The leader consults with group members and requests their input in work-related activities. In achievement-oriented leadership, the leader seeks continuous improvement and challenges followers to perform as per the established quality standards.

Followers’ Behaviors and Task Characteristics

The path-goal theory assumes that leadership behaviors will influence followers’ conduct and task characteristics, which, in turn, will impact followers’ motivation to work and achieve organizational goals. For example, the method in which a directive leader structures a task can motivate or demotivate employees. Structuring tasks is a form of job design associated with employee motivation, job satisfaction, low turnover, and organizational commitment (Al-Badarin & Al-Azzam 2017).

Job design refers to how a set of tasks or positions is organized in an organization. On the other hand, a supportive leader boosts follower’s self-confidence, motivating them to perform their job optimally. Al-Badarin and Al-Azzam (2017) assert that a leader’s lack of support or assistance can negatively impact an individual’s performance and health. In brief, this theory suggests that leaders can help their followers achieve organizational goals by selecting appropriate conduct for each situation and followers’ needs. This way, the leader can improve individual subordinate outcomes, including job satisfaction. An effective leader understands which leadership style or deportment is suitable for each situation and applies them appropriately.

Motivation

The path-goal theory believes that a leader can motivate employees to achieve organizational goals by applying the behaviors mentioned above. At its core, the postulation argues that a leader must engage in deportments that create a healthy and supportive work environment to increase employee performance. The underlying assumption is that followers will be motivated to perform if they believe they can complete the job. This assumption is based on Vroom’s expectancy theory which state that motivation can be achieved if an individual believes that (Reinharth & Wahba, 2017):

- Their efforts will result in intended performance.

- Achieving positive performance will lead to a desirable reward.

- The reward will satisfy a need. The desire to fulfill this need must be strong enough to “make the efforts worthwhile” (Reinharth & Wahba, 2017):

Vroom’s expectancy theory provides a framework for leaders to understand their subordinates’ individual motivational factors and determine which behavioral characteristics can help the individual achieve the desired outcomes. Based on the expectancy theory, the leader needs to understand what their followers find rewarding and then avail them when they achieve goals.

Behavioral Approach

While trait focuses on an individual’s personality and attributes, behavior centers on actions. This leadership approach focuses on a manager’s activities (what they do) and how they perform these actions. Until now, leaders’ effectiveness is still judged based on what they do. The literature on the aforementioned management approach is mainly based on two research programs – the Ohio State University (OSU) and the University of Michigan leadership studies. According to OSU researchers, the leadership deportment associated with effective group conduct are: consideration and initiating structure (task-oriented deportments).

Consideration behaviors are relational or “relationship-oriented” and are critical in creating and maintaining an excellent leader-follower relationship. Consideration deportments are marked by open communication with team members, respecting and valuing followers’ opinions and ideas, advocating for followers’ interests, and recognizing followers’ concerns and feelings. It involves building trust, respect, and camaraderie between followers and the leader (Behrendt et al., 2016). The initiative structure is task-oriented- it involves planning, organizing work, defining roles, scheduling work activities, establishing standard performance, and encouraging quality performance.

Leaders can exhibit both deportments and do not need to behave one way or the other. Behrendt et al. (2016) developed an integrative leadership behavior model that integrates task-oriented and relation-oriented conduct. According to the authors, task-oriented deportment will contribute to attaining shared goals, while relation-oriented support coordinated engagement between team members (Behrendt et al., 2016). The findings of this study are supported by a recent survey by Basker et al. (2020) which demonstrated that “initiating structure” deportments positively influenced a firm’s profitability while consideration behaviors positively impacted employees’ affective commitment and willingness to adapt.

However, it is worthwhile mentioning that these conducts can be effective in one situation but not in others. For example, OSU found that initiating structure was effective in some organizations they studied but had no effect on others (Bright et al., 2019). Consideration can improve employee satisfaction, especially in repetitive tasks or high-stress jobs. A considerate leader can initiate structure without reducing employee satisfaction; “initiating structure” can improve satisfaction by increasing task clarity.

Follower-Oriented Theories

The Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX)

The trait, behavioral, and situational approaches view leadership from the leader’s viewpoint. However, other theories look at leadership from the follower’s perspective. These follower-oriented theories focus on the dyadic relationship between leaders and their followers. For example, the leader-member exchange theory postulates that it is wrong to treat all group members the same way. The postulation focuses on the individual relationship between the leader and each group member (Park, 2017). The LMX theory describes leadership as a process focused on the interaction and relationship between the leader and each follower.

The theory works by first describing the relationship and then prescribing it. Descriptively, the theory asserts that there are always “in-groups” and “out-groups” in each group. In-groups refer to the people that identify with the group or have shared interests with the group (they believe they belong to the group). At the same time, “out-groups” are individuals that have no shared interest in the group (they feel they do not belong to the group) (Northouse, 2017). Within the organizational context, the followers will identify as the in-group or out-group depending on how well the leader works or their job satisfaction level (Northouse, 2019).

Therefore, leader should strive to create a high-quality relationship with their followers to optimize organizational productivity. When leaders create a high-quality individualistic relationship with the leaders, they increase work-related communication and access to supervisors, improving performance.

Other Follower-Oriented Approaches to Leadership

As mentioned earlier, there has been a renewed interest in leadership traits and conducts in recent years. Many organizations capitalize on leadership and management practices as innovative strategies to stay relevant and competitive in their external environment. This renewed interest has shed the spotlight on crucial motives, skills, and personality attributes that can transform the organization. Emerging from this trend are the six main leadership styles: transformational, transactional, autocratic, laissez-faire, task-oriented, and relationship-oriented. This section will explore transformational, transactional, authoritarian, and laissez-faire leadership styles – the latter two have already been discussed in previous sections.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is the process of changing or motivating individuals to change for the organization’s good. Transformational leaders must have the ability to encourage followers to commit to the organization’s goals to realize performance. They openly and effectively communicate the organization’s vision and implement effective strategies to generate followers’ interest and acceptance of their vision. A transformational leader (TL) must help employees look beyond their self-interests and prioritize the organization’s needs. There are four primary transformational leadership elements:

- Idealized influence: The transformational leader behaves in a manner that followers will want to emulate. They need to act as role models by engaging in highly-ethical and standard deportments.

- Inspirational motivation: Describes how the transformational leader can motivate followers to commit to the organization’s vision. The TL needs to inspire followers to accept the goals as their own to enhance team cooperation.

- Intellectual stimulation: Describes how managers inspire creativity and innovation in followers by challenging the status quo. They challenge followers to adopt new perspectives and encourage them to take risks and independently solve problems.

- Individualized consideration: Individualized consideration refers to the leader’s ability to tend to the followers’ individual needs.

This leadership style is associated with charisma: a TL leader’s ability to positively influence and motivate employees is attributed to their charisma. The leader is characterized by agreeableness, openness, experience, and experience. They use their attributes to energize and motivate followers toward achieving the desired goals. Past studies have positively correlated the positive organizational outcome to the TL’s deportment (Bright et al., 2019). The transformational leader’s conduct elicits feelings of trust and procedural justice perception, positively impacting follower performance and satisfaction (Bright et al., 2019).

When an organization faces turbulent situations, the TL can inspire followers to move past the problem. Transformational leadership’s slogan is that “the leader moves, the followers follow” (Bright et al., 2019). According to Steinmann et al. (2018), TL can lead to employee satisfaction, improved individual performance, and organizational commitment. In brief, the TL communicates vision, sets performance stands, and motivates and challenges employees towards achieving that goal. The leader works towards achieving the organizational goal by attending to each need of his/her follower.

Transactional Leadership

Transactional leadership refers to the exchanges that occur between the leader and followers. An example of a transactional leader is politicians promising to lower taxes if citizens vote for them. In the organizational context, organizational leaders can offer incentives, including promotions, career development, and monetary rewards, to get employees to meet the set goals (Northouse, 2019). Unlike transformational leaders who inspire change through personal values, commitment, and vision, transactional leaders bring change by offering rewards.

Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire leadership is a non-transactional leadership characterized by high follower autonomy. The manager typically relinquishes responsibility, does not provide feedback, and does the least to help employees satisfy their needs; they distance themselves from followers and make minimal contact. While Laissez-faire leadership has been intensely criticized, studies have shown that it decreases employee dependency and increases self-determination and self-competence (Northouse, 2019). In Laissez-faire leadership, followers are expected to make decisions without any direction or supervision from the leader.

Autocratic Leadership

Autocratic leadership is an authoritative management approach characterized by individual control. The leader uses his authority to control the followers and make decisions with very little to no input from the followers. Wang et al. (2019) describe autocratic leadership as “a governance style typified by individual control over all decisions and little input from group members.” Their decision is absolute, and the final say because they do not consider followers’ advice and opinion.

Autocratic leadership is effective in emergencies, such as the emergency unit in the hospitals. In the military, where the leader is responsible for people’s lives and any ineffective decision-making, can lead to life-threatening events. However, in the organizational context, autocratic leadership is weak. Authoritarian leadership is associated with flawed individual and organizational outcomes. According to Wang et al. (2019), authoritative leadership is negatively related to organizational commitment, job satisfaction, employee creativity, and employee performance. Therefore, it should not be used as the standard form of governance in the organization.

Critical Evaluation of the Behavior of Selected Leaders

Leader 1 Profile

Work Profile

I first encountered the above-mentioned leader while working at company X as an intern for six months. The company made equipment for automobiles; it ran two shifts with around twenty workers scheduled to work in every shift. Working under my supervisor’s authority allowed me to interact with him and understand his leadership style. I was able to observe how he responded to internal and external stimuli. I learned about his values, strengths and weaknesses, and personality traits by interacting with him. I worked in the company’s first shift and was managed by supervisor A, who was well-liked by his department’s employees, including myself.

Supervisor A was people-oriented, and workers often described him as a caring and friendly person. Not a day would go by without supervisor A emailing a group member to congratulate them on their accomplishments. He liked hosting social events, which he often called “team building events.” The social events were organized to enhance team relationships and bonding. In addition to his agreeableness, supervisor A was very involved in the day-to-day activities of his staff. I always saw him walking from plant to plant to remind us of what procedures we needed to follow while working. I hardly ever heard complaints about A’s leadership, but most staff always complained of how boring and monotonous their job was. Our work was repetitive because the process involved in the production was similar for each product.

We adhered to a strict schedule to achieve the established production rate at a given time. The instructions on working the production line were clearly outlined, and we only needed to report to work and execute our duties throughout the stipulated period. Despite the job structure being clear, supervisor A always gave instructions and reminded staff how to do the job correctly.

Due to the job’s monotony, absenteeism was common in our department. Supervisor A would always ask us to fill in for the absent worker in the name of “teamwork”. The missing members would get a lot of heat from the team when they reported to work, which strained individual relationships and team collaboration. While there were no complaints against supervisor A leadership, most of the workers hated their jobs.

Critical Analysis of Supervisor A’s leadership

Supervisor A’s leadership style can be analyzed based on the behavioral approach to leadership. As indicated earlier, this model asserts that consideration and initiating structure deportments enhance management efficiency. Creating structure is task-oriented conduct that allows efficient resource use (Bright et al., 2019). Supervisor A displayed ‘initiating structure’ features by directing followers on how to work the production line. Additionally, the fact that we had to adhere to a strict schedule to achieve the established production rate is characteristic of his ‘initiating structure’ leadership. According to Bright et al. (2019), features associated with initiating structure behaviors include:

- Scheduling work.

- Structuring tasks (deciding what needs to be done and how it shall be executed).

- Providing direction to followers.

- Encouraging followers to use standard procedures.

As mentioned earlier, the initiating structure allows efficient resource use to improve organizational outcomes. This stance was evident in this particular company because having a standard work structure allowed us to achieve the desired production rate each day. Constant production meant capitalizing on the time taken for value-added activities and reducing the inefficiencies caused by inactivity. From this perspective, it is logical to argue that the company’s initiating structure behavior can lead to efficient resource use.

In the previous section, I demonstrated that both consideration and initiating structure could significantly impact work conduct and attitudes (Bright et al., 2019). However, in this case, it can be argued that the initiating structure deportment in the company negatively impacted work behaviors and attitudes. Complaints and absenteeism characterized the nature of the work deportments and attitudes in this particular company. From a personal perspective, these complaints and frequent absenteeism were reflective of the employees’ job satisfaction. Interestingly, literature on organizational leadership postulates that demonstrating “appropriate conduct” can positively impact job satisfaction.

Supervisor A had the “right” conduct associated with job satisfaction. He is friendly, and supportive and strives to maintain good relationships with his team. By recognizing his followers’ achievements, supervisor A empowers them. According to Bright et al. (2019), consideration behaviors are associated with job satisfaction. This stance is supported by the LMX theory which asserts that a leader-follower relationship can increase job satisfaction, turnover, organizational citizen conduct (commitment), and job performance (Northouse, 2019).

Unfortunately, the situation at Company X contradicts the findings of these findings. Supervisor A had considerate behaviors, but none of them changed the employees’ attitudes and work-related deportment. While supervisor A’s followers liked their boss presumably for his conduct, they still had negative attitudes towards their job and preferred missing work.

This company’s situation leans towards literature that negates the idea that a leader’s deportment affects job and organizational outcomes. According to Northouse (2019), no research has found a definite link between task-related and relational management conducts with results, such as productivity, job satisfaction, and morale (p. 161). I think Northouse’s findings provide a logical explanation for the individual and team outcomes apparent at Company X. This paper, therefore, concludes that task-related deportment can improve efficient resource use (organizational outcome) but have no effect on the individual or team outcomes (collaboration and job satisfaction). Relational conduct does not affect job satisfaction or team outcomes in production companies. In this analysis, one thing that stands out is that the impacts of consideration and task-oriented behaviors are not consistent from situation to situation.

Although the above literature provides evidence to show the relationship between a leader’s conduct and organizational outcomes, they do not explain why Supervisor A is ineffective. I term his leadership ineffective because he fails to attain effective relational leadership’s core tenets: job satisfaction and positive team outcomes. Vroom’s expectancy theory can explain why supervisor A was ineffective in his management duties. Northouse (2019) states that “followers want to feel efficacious like they can accomplish what they set out to do” (p. 200).

It is highly likely that supervisor A’s followers do not feel efficacious due to their job’s nature. As mentioned earlier, the work structure and methods at the company’s production line were already established, and we only needed to show up and go through the motions. Therefore, it was hard for employees to associate any positive outcomes with our efforts.

The employees needed to feel like they were contributing something to the company. This perception is supported by Vroom’s expectancy theory, which states that employees feel motivated when they believe their efforts will result in the desired achievement. However, in this case, production employees cannot correlate their efforts to the organization’s outcomes because their work is monotonous and pre-determined. Based on the expectancy theory, Supervisor A needs to identify each of his followers’ motivational factors, develop goals based on these factors, and after that, reward them for achieving those goals.

Because production employees need to be efficacious to be motivated, the supervisor should apply a different leadership approach. Instead of being exclusively supportive, supervisor A should also be participative to provide his employees with control and work autonomy. The participative management approach involves supporting the team in a way that encourages involvement. This way, supervisor A’s followers can develop a link between their efforts and outcomes or performance.

Leader 2 Profile

My second experience with the above leadership theories was while working at institution Y as an associate. Manager B and I were hired simultaneously, and I worked alongside him for three years. I learned of his leadership style through our day-to-day interactions, meetings, discussions, etc. From these interactions, I learned about his values, traits, and attributes. I also observed his response to internal and external stimuli, including stressors, which allowed me to perceive his conduct.

Work Profile

Manager B had inferior credentials compared to the rest of the leadership team. Most of us believed that one must possess high levels of knowledge, ability, and skill in his specialization area to be successful. However, because manager B had inferior academic qualifications, we thought he lacked what was needed to climb the corporate ladder. Despite his weak expert power, manager B had a strong personality that naturally attracted people to him. He was sociable and had excellent communication skills, which played a critical role in his leadership performance. This skill came into play and was instrumental when we all were required to get public members to enroll for a government-related service. Because of his wit and sociability, manager B outperformed everyone on the team. Manager B consistently scored highly in human relations and friendliness in his performance reviews. Therefore, we associated his success with his charisma and personality.

In hindsight, manager B wasn’t just charismatic but also had high emotional intelligence. He displayed both social and personal competencies that influenced his leadership. He knew how the team felt about his qualifications vis-à-vis his leadership competence but never engaged in such conversations. Instead, he exuded confidence, self-awareness, and emotional control, even in the face of biased criticisms and high stress. He chose to logically reason with the team rather than react to their subjective opinions.

Concerning his work practices, manager B cared deeply for his followers. He believed in seeking continuous improvement in every task. His slogan was that success and achievement mean nothing if there is no continual growth or progress. Therefore, he always encouraged his followers to find new ways of carrying out their tasks. He conducted weekly meetings to address action items, encountered problems or barriers in the last week, and track employees’ performance.

Manager B would set and communicate his goals and then use his “charisma” to influence them to accept or comply with his plans. He would always ask his followers how they felt about his goals and how he can help them overcome barriers-if. He paid attention to the individual performance of each of his followers and provided support where needed. Within two years, manager B was promoted to the line manager position while the rest were still department supervisors.

Critical Analysis of Manager B Leadership Style

Manager B’s leadership can be analyzed based on the trait approach and transformational leadership theory. The trait approach is based on the argument that leaders are born, i.e. some people are born with the right traits to be leaders. According to Bright et al. (2019), the qualities that make one a leader include drive, self-confidence, high tolerance for stressors, expertise, cognitive ability, and desirable personality. Manager B possessed some of these skills, including having a preferable character, self-confidence, and high tolerance for stress. High-stress forbearance, self-regulation, and confidence were reflected in his ability to control his emotions even when his peers regard him as inferior due to his qualifications.

The trait approach theories suggest that possessing the right skills is a strong predictor of leadership success. Research findings have shown that some leadership traits can affect leader effectiveness. For example, extraversion and conscientiousness are strongly correlated to leadership effectiveness (Norrthouse, 2019). Recent literature has also confirmed the notion that some personality traits can positively impact organizational outcomes. Hu and Judge’ (2017) demonstrated a strong correlation between leader conscientiousness and agreeableness to team performance. Therefore, it can be surmised that manager B’s traits contributed to his success as a leader.

Extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness are associated with transformational leadership. Bright et al. (2019) describe transformational leaders as charismatic individuals. Manager B also demonstrates at least three transformational leadership elements: individualized consideration, inspirational motivation, and intellectual stimulation. He exhibits individual consideration by paying attention to his followers’ performance, showing that he also attends to his followers’ specific needs. Manager B demonstrates intellectual stimulation by encouraging his employees to seek new ways of doing their job. Intellectual stimulation can tap into and enhance followers’ creativity. He inspires his followers by encouraging them to seek continuous improvement and by steering his followers towards desired goals.

Manager B’s transformational leadership can be linked to his leadership effectiveness. A study by Steinmann et al. (2018) showed that transformational leadership is positively associated with job satisfaction, team performance, job attitudes and work conduct. Another survey by Prochazka et al. (2018) attributes these outcomes to the leaders’ traits. According to Prochazka et al. (2018), personality traits mediate the TL’s success. The behaviors displayed by a TL can foster leader-follower relationships, which, in turn, positively influence the leader’s success.

Summary of the Learning

Lessons

I have gained an in-depth understanding of organizational leadership from this paper. The most important lesson is that no leadership style or behavior is perfect for all situations. Managers need to adjust their administrative strategies to suit their followers’ needs and the prevailing atmosphere – each circumstance has its demands, and so do followers. Therefore, an effective leader should always analyze the situation and determine which leadership strategy or conduct is appropriate for that situation. I will be directive when tasks are complex and supportive when tasks are tedious, stressful, or dull. Furthermore, I will be participative when my followers need control and achievement-oriented, especially if my followers need to excel.

The second lesson is that followers’ needs, motivations, and conduct influence one’s chances of success. Unless employees have the appropriate conduct and inspiration to work, a leader cannot triumph. Therefore, I have to influence and inspire the right attitude and motivations in my followers to achieve organizational goals. There will always be members who are “in-groups” and others who are “out-groups” for every team that I lead. This statement implies that each of my followers will have unique needs, expectations, and motivations. Therefore, I will make individual considerations while developing goals and work structures. Followers need to know they are contributing something to the company to feel efficacious.

The third lesson is that traits, especially one’s personality, can affect their chances of being successful. Qualities such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are associated with leadership success. Other desirable traits include drive, tolerance, sociability, intellective, charisma, and creativity. According to Bright et al. (2019), people are not born with leadership traits, often develop them. While I may not be naturally endowed with these traits, I can learn and nurture them.

Another critical lesson learnt is that leader-follower relationships are crucial in increasing job satisfaction, commitment, and team performance. Effective leader-follower interconnections can also improve work attitudes and conduct. Literature places a unique emphasis on transformational leadership, a model capable of improving individual, team, and organizational outcomes (Prochazka et al., 2018). Finally, it is worth mentioning that studies on whether leadership behaviors (supportive and ‘initiating structure’) impact organizational outcomes are inconclusive. Some researchers posit that these behaviors can improve job satisfaction, while others argue that they do not. As a leader, I can evaluate my effectiveness based on three major indicators:

- He/she is effective in their in-role performance.

- The group he leads is successful and performs well.

- If their followers consider them leaders.

Strategies I Would Implement to Improve my Leadership Capacity

To better my leadership capacity, I need to improve my interaction with staff and develop appropriate problem-solving skills. I also have to enhance my task-related approaches to foster my managerial efficacy. Given that leader-follower relationships are crucial in leadership success, I need to create effective relationships with my followers. I will achieve this goal by adopting an open communication strategy. Findings by Mayfield and Mayfield (2017) support this perspective by revealing that effective communication can improve relationships and enhance conflict resolution. Furthermore, it can drive a positive workplace outcome, including employee performance.

I can organize a dialogical interchange, which integrates debate, reflection, and discussion of ideas with staff to build a mutual and reciprocal relationship characterized by information sharing and mutual interdependence. My task approach is directive: I typically create and assign tasks to employees and provide guidance on how to execute the allocated responsibilities. Because I do not work in a high-risk environment (hospitals or the military), I need to change my approach. I will establish an organizational culture where employees need to take on leadership roles to provide them with autonomy and control. While encouraging joint responsibility, I will also ensure that each worker is assigned to perform an entire task to improve accountability while concurrently providing autonomy and control.

I also need to overcome my defensive conflict management strategies to be effective. Like manager B, I need to develop my emotional intelligence to overcome this weakness. I can take problem-solving classes to improve the way I address problems. To resolve ethical dilemmas, I will use open dialogue and effective communication. My interactions with staff will always be honest, respectful, and considerate to build trusting relationships.

Conclusion

No leadership style or approach is applicable in all situations. An effective leader needs to analyze the prevailing conditions, and each of his followers’ needs to determine the efficacy of a desirable management strategy or conduct. Appropriate leadership traits and leader-follower relationships have a positive impact on organizational outcomes. However, research on the effects of leadership behaviors on organizational outcome has been inconsistent. Therefore, more research needs to be done on the aforementioned topic to allow leaders to determine the most appropriate management approach.

References

Al-Badarin, R. Q., & Al-Azzam, A. H. (2017). Job design and its impact on the job strain: Analyzing the job as a moderating variable in the private hospitals in Irbid. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 7(3), 152 – 169. Web.

Basker, I. N., Sverdrup, T. E., Schei, V. & Sandvik, A.M. (2020). Embracing the duality of consideration and initiating structure: CEO leadership behaviors and small firm performance. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(3), 449–462. Web.

Behrendt, P., Matz, S., & Göritz, A. S. (2017). An integrative model of leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), 229–244. Web.

Bright, D. S., Cortes, A. H., Hartmann, E., Parboteeah, K. P., Pierce, J. L., Reece, M.,… & O’Rourke, J. S. (2019). Principles of management. OpenStax.

Huang, L., Krasikova, D. V., & Harms, P. D. (2020). Avoiding or embracing social relationships? A conservation of resources perspective of leader narcissism, leader-member exchange differentiation, and follower’s voice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(1), 77-92. Web.

Hu, J., & Judge, T. A. (2017). Leader–team complementarity: Exploring the interactive effects of leader personality traits and team power distance values on team processes and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(6), 935–955. Web.

Mayfield, J., & Mayfield, M. (2017). Motivating language theory: Effective leaders talk in the workplace. Palgrave Macmillan.

Northouse, P. G. (2019). Leadership: theory and practice (8th ed.). Sage Publishing

Park, S. (2017). The effects of the leader-member exchange relationship on rater accountability: A conceptual approach. Cogent Psychology, 4(1), 1–11. Web.

Prochazka, J., Vaculik, M., Smutny, P., & Jezek, S. (2018). Leader traits, transformational leadership and leader effectiveness: A mediation study from the Czech Republic. Journal of East European Management Studies, 23(3), 474-501. Web.

Reinharth, L. & Wahba, M. A. (2017). Expectancy theory is a predictor of work motivation, effort expenditure, and job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 18(3), 1–13. Web.

Steinmann, B., Klug, H. J. P., & Maier, G. W. (2018). The path is the goal: How transformational leaders enhance followers’ job attitudes and proactive behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 1–15. Web.

Vidal, G. G., Campdesuñer, R. P., Rodríguez, A. S., & Vivar, R. M. (2017). Contingency theory to study leadership styles of small business owner-managers at Santo Domingo, Ecuador. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 9, 1–11. Web.

Wang, Z., Liu, Y., & Liu, S. (2019). Authoritarian leadership and task performance: The effects of leader-member exchange and dependence on leader. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 13, 1–15. Web.