In Germany, microfinance comprises funding for small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as well as start-up entrepreneurs. Therefore, these financial measures in Germany entail only small amounts and are mostly done relative to entrepreneurial activities. Even though Germany has among the most efficient banking sectors in the EU, small and young enterprises face certain problems when accessing small amounts of funds from external providers (Diriker, Landoni & Benaglio, 2018). The country has an advanced cost-to-earnings ratio, which makes microfinance a less profitable financial activity for banks.

The amounts provided by the microfinance institutions in Germany are often too small to offset the high risk of operating costs because of certain reasons attached to the specific borrowers. For example, high risk of default, difficulties in assessing the borrower’s credit standings, and the small size of the borrower’s business are common problems. Consequently, the loan amounts end up earning very little for the microfinance institutions (Diriker, Landoni & Benaglio, 2018). Even though the microfinance business is still economically viable in Germany, small-scale investments often fail to take off because banks and other large financiers are reluctant to provide adequate funds.

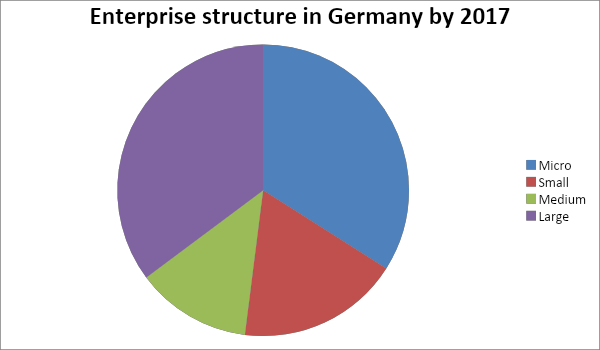

Nevertheless, the micro-enterprises and their financial demands have continued to gain the attention of policymakers, politicians, and researchers since the 1990s. Micro enterprises have increasingly become important for labor policies as they create additional job opportunities (Schmidt, 2017). When the EU definition of enterprises changed in 2005, the term ‘micro enterprises’ was adopted as the name of the fourth category of business that comprises those enterprises with up to 9 employees, annual turnover of up to €2 million, and an annual balance sheet of up to €2 million (Diriker, Landoni & Benaglio, 2018). Consequently, many enterprises in Germany fall within this category of businesses (figure 1).

The German Microfinance Institute (DMI) was founded in 2014 with an aim of establishing a standardized countrywide system for microlending. The only institutions that provide microfinance to small and medium enterprises in Germany, and which are now controlled by DMI, are known as Grunderzentren (business start-up caters). These institutions are mainly nonprofit organizations that act as one-stop shops for future entrepreneurs with an interest in offering services necessary to begin viable enterprises (Diriker, Landoni & Benaglio, 2018).

Noteworthy, there are only two such institutions, ARP-Krdit Berlin and Hamburger Kleinstkreditprogramm, that issue over 100 loans per year. The Grunderzentren institutions provide loans at an interest rate of between 0% and 8.5% or have to use the conditions set by Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW). The KfW provides microloans as “small credit” ranging between €5,000 and €25,000 at an interest rate of 8.67% (Diriker, Landoni & Benaglio, 2018). Noteworthy, the loans must be given out by local retail banks since the law does not allow the microfinance lenders to issue them directly to the borrowers.

Microfinance in Austria

Although not initially recognized as a form of microfinance, microlending to startups, small, and medium businesses in Austria has been there for over 50 years. The first micro-lending system, which began in the late 1960s, is the cooperation between the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Vienna (Wirtschaftskammer Wien) and bigger banks to provide loans of up to €6,000 for already existing small enterprises and €7,000 for startups with an annual interest rate of 3%. The chamber has been providing information as well as advice to the program and obtains credit applications from the banks (Diriker, Landoni & Benaglio, 2018).

After receiving the applications, the chamber screens the proposals to determine whether or not to provide funds to the applicants. Once the chamber approves the applications, it sends the information to the banks that directly fund the applicants. Currently, over 450 credit applications are approved every year in Austria through this program (Diriker, Landoni & Benaglio, 2018). Therefore, it is evident that the state of microfinance in Austria is still less developed, given the small number of applicants and the presence of few providers of loans.

Criticism Regarding the Example of Africa

While thousands of people and groups have moved out of poverty through these programs, microfinance has equally received criticism due to its efficiency in reducing poverty. Critics cite the continuous state of poverty in certain regions, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia where millions have been pumped into microfinance programs but with minimal impact.

In sub-Saharan Africa, various studies have shown that microcredit programs fail to make an impact on the lives of the targeted groups for various reasons. First, the human factor has been cited as a major obstacle in realizing the full potential of microlending (Mia, et al., 2019). For instance, it has been shown that due to minimal or no follow-up, borrowers have the freedom to use the loans for personal consumption rather than using them as capital for business (Chui, 2017). After spending the money, the borrowers return to the state of poverty and even find it difficult to repay the loan because they still have no business to generate money.

Secondly, other researchers have argued that microcredits are not necessarily designed to improve the state of development and human living standards. Micro credits are indeed anti-development as they strengthen poverty in the developing world (Bateman, 2012). According to this view, microcredits contribute to unsustainable indebtedness mainly at the micro but also at the macro-level and have little contribution to sustainable development (Chui, 2017). Rather, these programs provide credit to poor people without giving them advice on entrepreneurship, which ends up burdening the poor people with debts. Therefore, the only beneficiaries are the loan providers as they will receive interest rates on loans provided to the poor people.

Evaluation

In Germany, the role of DMI is effective in monitoring and controlling the interest rates charged by various providers of microcredits to startups, small, and medium businesses. Specifically, DMI has established a standardized countrywide system for microlending. The Grunderzentren institutions have maintained relatively low levels of interest rates, with the highest set at 8.5% and the lowest at 0% (Forcella & Hudon, 2016). These institutions are mainly nonprofit organizations that act as one-stop shops for future entrepreneurs with an interest in offering services necessary to begin viable enterprises.

Only ARP-Krdit Berlin and Hamburger Kleinstkreditprogramm issue over 100 loans per year in the country (Forcella & Hudon, 2016). Also, most Grunderzentren institutions provide loans at an interest rate of between based on the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) model, which ensures that rates are maintained at a relatively low level. The KfW provides small credits ranging from €5,000 to €25,000 at an 8.67% interest rate (Forcella & Hudon, 2016). All these loans are issued by the local retail banks since the law does not allow the microfinance lenders to issue them directly to the borrowers.

In Austria, microlending is still underdeveloped and there are few players in the sector. The cooperation between the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Vienna (Wirtschaftskammer Wien) and bigger banks in the country is the major player and provides loans of up to €6,000 for already existing small enterprises and €7,000 for startups with an annual interest rate of 3% (Forcella & Hudon, 2016).

In this cooperation, Wirtschaftskammer Wien plays an important role in providing information as well as advice to the banks. On their part, the local commercial banks obtain applications for loans from interested borrowers on behalf of Wirtschaftskammer. The chamber then screens the proposals to decide the specific borrowers worth receiving loans and then sends the information to the banks (Forcella & Hudon, 2016). Therefore, it is evident that the state of microfinance in Austria is still less developed, given the small number of applicants and the presence of few providers of loans.

For the purpose of evaluating the impact of microfinance, it is worth analyzing the claim by Bateman that these programs have done very little to alleviate poverty in the developing world. The central argument in Bateman’s thesis is that microfinance is largely antagonistic to both sustainable economic and social development and cannot reduce poverty sustainably (Bateman, 2012). Even the realized benefits from microfinance programs in the developing world have been very minimal. Noteworthy, Bateman’s argument makes sense from a practical perspective, given the trends already observed in Africa and other developing nations (Bateman, 2012).

For instance, despite having thousands of microcredit programs and huge sums of money sent to the poor for more than five decades, the level of poverty in Africa is still high. In fact, more than half of the population in sub-Saharan Africa lives below the poverty line. It can be argued that the problem with microfinance is that the lending institutions are not interested in educating and guiding the borrowers on how to invest the money. Rather, they are interested in the financial returns they make from the business. Indeed, because there is largely no follow-up, people end up spending money on personal consumption, which cannot reduce poverty.

Summary

Despite the criticism of microfinance, there are several advantages that these programs have, especially in the developing world. For instance, microfinance institutions can easily help people to obtain capital for business ventures (Botti, Corsi & Zacchia, 2018). Even with small amounts of money, people in poor regions can access loans and establish or boost businesses. Secondly, microfinance allows people who are not creditworthy to the bank. Microfinance is therefore an important instrument of development policy. Furthermore, microcredit now works worldwide and mainly in many developing and emerging countries such as India.

Future Prospects

Currently, microfinance is expanding from the developing world to developed nations as more people seek to establish and run their own businesses instead of relying on employment. It is estimated that the trend will continue in the next few decades but with a new direction. For instance, main banks have started venturing into the microfinance sector as they establish their own programs for providing small loans to startups, small, and medium ventures. In addition, the rise of Internet-based lending systems will have a significant impact on microfinance. As an example, people will be able to access small loans using Apps or other Internet-based applications without the need to apply through banks and other institutions. It might become an entirely online business but this will largely depend on the level of trust between the two parties.

References

Bateman, M. (2012). The role of microfinance in contemporary rural development finance policy and practice: Imposing neoliberalism as ‘best practice’. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(4), 587-600. Web.

Botti, F., Corsi, M., & Zacchia, G. (2018). A new European microfinance panel data set: The European Microfinance Network survey 2006-2015. European Microfinance Network, Brussels.

Chiu, T. K. (2017). Factors influencing microfinance engagements by formal financial institutions. J Bus Ethics 143, 565–587. Web.

Diriker, D., Landoni, P., & Benaglio, N. (2018). Microfinance in Europe: Survey report 2016-2017. European Microfinance Network, Microfinance Centre.

Forcella, D., & Hudon, M. (2016). Green Microfinance in Europe. J Bus Ethics 135, 445–459. Web.

Mia, M. A., Lee, H. A., Chandran, V. G. R., Rasiah, R., & Rahman, M. (2019). History of microfinance in Bangladesh: A life cycle theory approach. Business History, 61(4), 703-733. Web.

Schmidt, R. H. (2017). Microfinance-once and today (No. 48). SAFE White Paper.