Introduction

It is known that leadership is a type of management interaction based on the most effective combination of various sources of power for a given situation, aimed at encouraging people to achieve common goals. Strength and compulsion in leadership are often replaced by drive and excitement. As a result of the leadership approach, influence is based on people’s acceptance of the leader’s demands without explicit or direct exercise of power. The leader’s ability to influence people enables him to exercise the power and authority that is characteristic of modern military leadership.

In the world of business and in management science, transformational leadership is today considered the most effective style, and there is a certain situation of stagnation, “resting on laurels” due to the fact that the further development of leadership theory does not require fundamental improvements and significant modifications. However, practice shows that this style of leadership, in its currently applied form, is not always able to provide organizational excellence.

A number of disadvantages of transformational leadership can be noted – for example, results obtained in a number of studies have shown that the advantages of transformational leadership are often overestimated. In particular, in the context of its influence on the productive activities of employees, it does not always turn out to be more effective than transactional. This was supported by studies by Kahai, Sosick, and Avolio (2003), which examined the effects of different leadership styles on the creativity of e-brainstorming (EBS) participants. The results of these studies showed that in the context of the implementation of the transformational leadership style, EBS participants did not perform significantly better in the unusualness of the ideas they produced than in the context of transactional leadership (Kahai, Sosick, & Avolio, 2003).

Even more interesting results were obtained in the studies of Jaussi and Dionne (2003). In accordance with them, it turned out that the transformational leadership influence in some cases can even have a negative impact on the creativity of the subject in the context of both individual and group creativity (Jaussi & Dionne, 2003).

Research carried out in this area shows that transformational leadership is more effective in stimulating the creativity of followers in cases where the group generating new ideas are as heterogeneous as possible in its composition (it has participants with different views, educational levels, professional interests, etc.), when direct contacts of the transformational leader with the generators of ideas at the moments of their creative activity are minimized. Moreover, transformational leadership can turn out to be completely ineffective when the focus on innovation is replaced by the exploitation of already known products and technologies for the sake of commercial gain or the interests of investors and higher-ranking executives.

Thus, there is a clear need to modify the styles of organizational leadership that are popular today – specifically, transformational leadership. In particular, military leadership, which develops much more dynamically than organizational leadership, can play an important role in overcoming the above deficiencies, which is due to the exceptional uncertainty of hostilities in modern conditions, the need to participate in hybrid wars, as well as the need for quick and effective training of the armed forces. The external and often internal environment of modern business, the need to take into account the diverse and even conflicting interests of stakeholders resemble hybrid warfare, but business leaders call this uncertainty, chaos, and entropy, instead of conducting an impartial analysis of the situation and working out the optimal situational solution.

Background

Military researchers argue that the service and combat activity of a serviceman requires a complex of certain qualities, which, forming the professional structure of his personality, at the same time represent the basis of leadership in a team. The most important of them are high intelligence, purposefulness, ability for psychoanalysis and reflection, resistance to stress, emotional balance, ability to manage oneself, empathy, organizational insight, exactingness, professionalism, sociability, etc. (Steadman, 2018).

The following set of qualities is proposed as the basis for the authority of the leader-commander: activity in the social life of the unit; professional training, deep knowledge of military affairs, good military-technical training; love for profession, responsible and creative attitude to work; moral purity, honesty, truthfulness, hard work, modesty, dignified behavior in everyday life; organizational skills, efficiency, practical sense, ability to timely notice and support everything new and advanced; discipline, diligence, dedication, initiative, endurance, self-control, perseverance, courage, the ability to endure the hardships and deprivations in military service; tactfulness, high exactingness combined with care, fairness and respect (Steadman, 2018).

Thus, as can be seen from the above characteristics, the competence of a military leader has much in common with the competence of a transformational leader. An even greater similarity to the concept of transformational leadership is found when considering the so-called steps of leadership growth of military leaders (Mattis & West, 2019):

- Internal Leadership. It includes diagnosing leadership inclinations, determination of the existence of prerequisites for the emergence and development of leadership.

- Situational, or contextual, leadership (micro leadership). It manifests itself when a person takes on the role of a leader, depending on the current situation and in a specific context.

- Team, or tactical, leadership (macro leadership). The leader constantly leads his/her team, being its inspirator. He/she sets tactical goals and strives to achieve them.

- Systemic, or strategic, leadership (meta leadership). It implies setting strategic goals, forming the company’s vision, defining far-reaching plans and development prospects. Leader does not even motivate, but inspires.

Robert T. Kiyosaki, the author of 8 Lessons in Military Leadership for Entrepreneurs, rightly notes that “men and women in the military have unique key skills and backgrounds for entrepreneurship. In many cases, they are taught to “do the impossible.” Most college graduates only know how to “find a job.” By their nature, people trained to do the impossible – and willing to pay the necessary price (often called the ultimate sacrifice) – are strikingly different from those who are taught to “seek high-paying jobs with a good package of benefits” (Kiyosaki, 2015, p. 3). The author, considering the differences between success in the civilian world and in the military, concludes that business success requires the same core skills, values, and leadership qualities that are formed in the military. Considering the above, it seems expedient to investigate the possibilities and potential benefits of attracting post 9/11 military veterans to conduct leadership activities in business organizations, with the aim to improve leadership practice, talent management, and, as a consequence, organizational performance.

Statement of the Problem

Based on the presented research, it is evident that although leadership research is well-established in both military and non-military settings, two research gaps are evident. One, the overlap between the fields is not sufficiently researched; it is not necessarily clear which traits and competencies are shared and which are unique to either setting. Two, the specifics of the transition process are not currently clear. Although some of the research points to a military background being generally beneficial to performance in a civilian line of work, findings such as DeVault (2017) point to some competencies beneficial in the military becoming hindrances in the transition process. Clarifying these issues can be a significant benefit to leadership research by informing future leadership development strategies or training and accommodation programs targeting veterans transitioning to civilian work.

Management science operates with two concepts – leadership and management. In the military arena, there is a third concept: command. However, this word evokes unpleasant associations for most civilians; however, it is due lack of proper understanding. NATO defines command as the authority vested in a person to direct, coordinate, and control military forces (Kowalski & Prescott, 2019).

Command is what a third party gives to a person; it grants him/her powers that come with responsibilities and functions. Responsibilities can be delegated or divided, but the commander is still responsible for what happens. In the British armed forces, the monarch grants the right to command; in the US military, the president. In business, the right to command is given by the owners of the company, who are most often its shareholders. Functions include leadership, decision making and oversight, and these are carried out in accordance with the direction given by the third party.

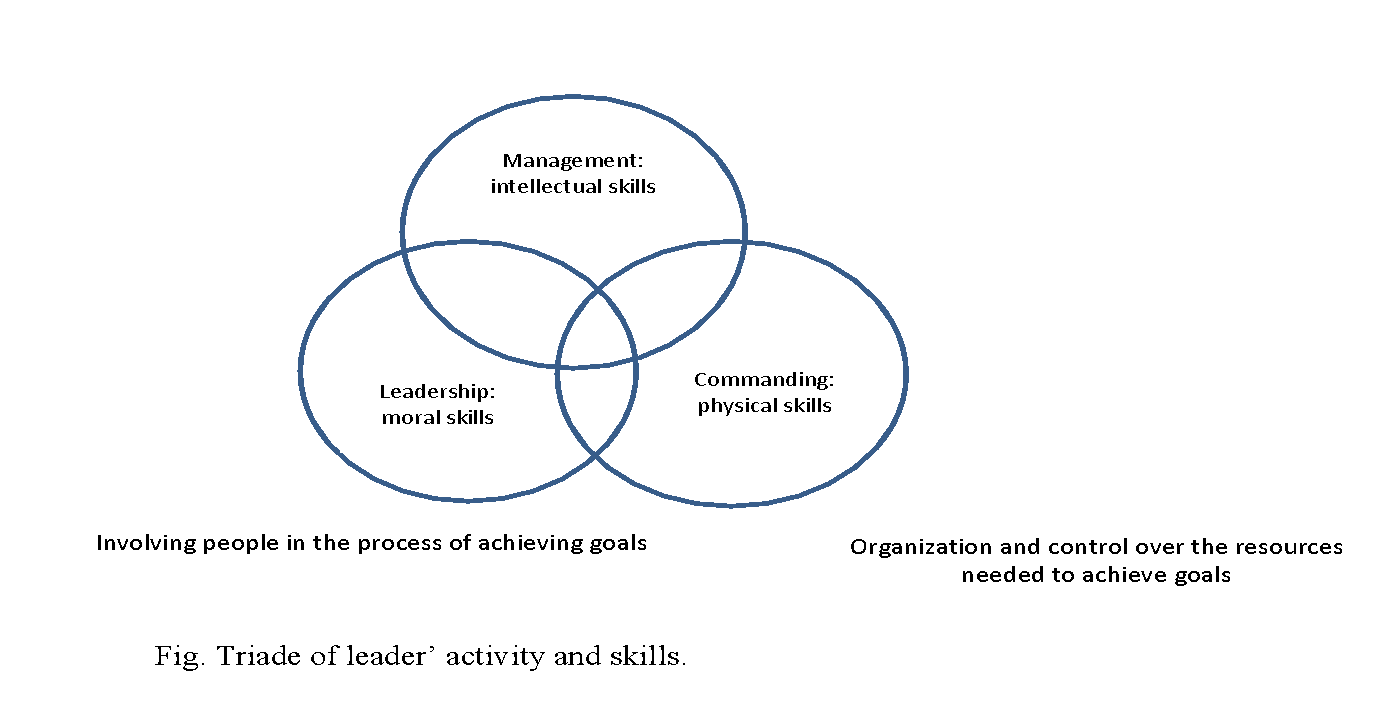

Business thinking is forced to deal with an imposed system of two-pronged management and leadership, and often fruitless discussions are held, since no one can distinguish between leadership and command. Command in this case is defined as an authoritarian leadership style and is rejected as a relic of the industrial era and Fordism. However, in fact, the real practice business system is a triad of command, leadership, and management, as shown in the figure below.

Powers, responsibilities and functions of management.

There is the task to analyze the possibility of building synergy between management, leadership, and command, in which the experience of military veterans who took part in hybrid wars, can become valuable, helping to introduce in business organizations best elements and practices of military leadership.

Purpose of the Study

Applications of military leadership in non-military contexts are another relatively untapped area of research. Haymaker (2019) points to certain issues military veterans may face when transitioning to civilian jobs, but link them to differences in expectations rather than any acquired competencies or personality traits. The study will attempt to examine the direct transition of military leadership traits into civilian organizations while systematization of transferable traits desirable in business. The purpose of study is to develop a complex of recommendations on the attraction of Post 9/11 combat veterans to carry out leadership functions in business organizations, based on modelling changes and development training programs for employees, on the example of Threat Tec/Yorktown Systems Group – a joint venture of contracted companies operating to fulfil contractual operational environment requirements for the Army’s Training & Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

Conceptual Framework

The study is based on theoretical implications of business and military leadership. Transformational, transactional, and situational leadership theories will be applied as the theoretical basis for the study, as well as theoretical background of military leadership, strategy and tactics in hybrid warfare. The overall research philosophy is social constructivism – an approach according to which any cognitive activity of a person is a construction, implying three key concepts – goal setting, justification and creativity.

Research Questions

The research implies the following questions:

- What are the specific leadership traits of military veterans?

- What are potential challenges of former military officers and enlisted when starting coaching and work in business companies?

- What can be possible combinations and convergence of transformational leadership and military leadership?

- What is the potential impact of military culture on corporate culture and HRM practices?

- What are the possibilities of using military leadership tools and paradigms in diversity management?

Nature of the Study

The study is qualitative; methodology tools include content analysis of secondary sources, as well as qualitative empirical research with the use of semi-structured interviews revealing current problems in organizational leadership and performance, and potential of military veterans’ experience application, including leadership practices in the conditions of hybrid warfare. The results of empirical research will be processed based on Corbin and Strauss categorization in frames of grounded theory, which is used to study a wide range of problem areas and practice settings.

Significance of the Study

The study will serve as an innovative direction in the field of leadership studies, proposing a synergetic combination of business leadership and military leadership with the aim to build the culture of participation in the targeted organization and improve organizational performance. This determines the scientific significance of the study. Practical significance is determined by developed complex of practical recommendations which can be applied in any company willing to improve its leadership practices, corporate culture, talent management, and performance.

Definition of Key Terms

Transformational leadership: “a leadership style that can inspire positive changes in those who follow” (Murphy, 2019, p. 42).

Transactional leadership: “the style of leadership which involves motivating and directing followers primarily through appealing to their own self-interest” (Murphy, 2019, p. 34).

Situational leadership: “a leadership style in which a leader adapts their style of leading to suit the current work environment and/or needs of a team” (Murphy, 2019, p. 27).

Command: the authority vested in a person to direct, coordinate, and control military forces (Kowalski & Prescott, 2019, p. 82)

Post 9/11 veterans: veterans who took part in the USA, NATO, and UN global operations after 9/11 terrorist attack (the definition proposed by author).

Hybrid warfare: “the synchronized use of multiple instruments of power tailored to specific vulnerabilities across the full spectrum of societal functions to achieve synergistic effects” (Cullen, 2017).

Conclusion

The business environment is changing increasingly more rapidly. In modern conditions, many organizations operate in a turbulent environment and are forced to carry out constant changes to maintain their competitiveness. The competencies and characteristics of the organization’s leader must be sufficient to manage reactive change. In this sense, the experience of military veterans who have participated in military operations in Iraq such as Operation Desert Storm, and more recently in Syria, where the conditions for waging hybrid warfare have become even more complex, is invaluable for developing organizational leadership in business. The proposed study will make an attempt to examine the direct transition of military leadership traits into civilian organizations while systematization of transferable traits desirable in business.

Therefore, the adaptation of the study would propose specific strategies to efficiently integrate and utilize Post 9/11 combat veteran’s intrinsic leadership experiences in their transition into a civilian business environment. The study suggests inclusion of empirical research based on quantitative methods – interviews, observation, and surveys, with the aim to identify transferable traits in veterans suitable to be applied in business, as well as potential challenges and benefits both for the companies and for Post 9/11 veterans. It is assumed that a combination of qualitative research methods will enable a deeper understanding of the issue context, research questions, and allow the developing better solutions.

References

Cullen, P., & Reichborn-Kjennerud, E. (2017). Understanding Hybrid Warfare. GOV.UK. Web.

Deloitte (2018). Leadership competency modeling: From competence to capability. Web.

Deloitte (2017). High-impact leadership. Web.

Jaussi, K. S., & Dionne, S. D. (2003). Leading for creativity: The role of unconventional leader behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(4-5), 475–498. Web.

Kahai, S. S., Sosik, J. J., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Effects of leadership style, anonymity, and rewards on creativity-relevant processes and outcomes in an electronic meeting system context. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(4-5), 499–524. Web.

Kiyosaki, R. T. (2015). 8 Lessons in military leadership for entrepreneurs. Plata Publishing.

Lin, S., Scott, B., & Matta, F. (2018). The dark side of transformational leader behaviors for leaders themselves: A conservation of resources perspective. The Academy of Management Journal, 62(5), 1-59.