Introduction

Globalization creates new problems and opportunities for global retailers like Nike, Co. To survive bad remain competitive, Nike uses foreign labor and outsourcing strategies in its production. The US economy depends upon international labor supply and international business relations. This in itself would contribute to the surge in exports to the developed economies. However this overlooks the importance of outsourcing, the disintegration of the production process whereby production activities have been done abroad are combined with those done at home. In general, outsourcing is one of the most effective ways to improve the position of the company and introduce new technologies and human resources. There are several problems with outsourcing faced by the state and companies.

Production Chain

The uniqueness of Nike’s production chain is that it is flexible and allows the company to adjust its systems in a new country. For Nike, the short-term relationships are based on the selection of suppliers. The purpose of the model is to use market pressure and available capacity to strike the best deal. Introduced by Nike, the short-term model tries to strike the best deal by competitive bidding or leveraging market conditions. This approach puts to use free-market competition for competitive leveraging as a route to tactical purchasing (Fisher, 2006; see appendix 1). The short-term model is characterized by a lack of sophistication in relations and involves a lot of hard bargaining, often, accompanied by tough negotiations. Nike’s production chain also has its comparative advantages. At Nike, short-term buyer and supplier relationships give more flexibility to the buyers to source products from many different suppliers as they do not have any long-term purchase commitments with one supplier. Similarly, the suppliers have the flexibility of supplying products to many different buyers. The capability enhancement of Nike’s supplier can be used to supply products to different buyers with an increase in market demand of particular goods or components (Bateman and Snell 2004; Korzeniewicz, 2003).

Outsoaring in Asian countries: Child Labor, Human Rights

In cases where this is technically possible, the cost advantage of outsourcing in Asian countries will probably apply to parts of production processes, leading to outsourcing by the developed economies. Indeed in the current period, the large growth in merchandise trade relative to merchandise production of Nike in the less developed economies can be attributed both to the increased number of exporting final goods to the developed economies and also to the growth of the latter’s outsourcing. Nike is often criticized for using child labor and violation of labor rights but still, this information is rejected by the company.

Nike recognizes that when rules limit direct investment and outsourcing, both producers and labor want enforcement of labor standards abroad to maintain competitiveness for their products. Once the rules are relaxed, the interests of producers and consumers diverge, as low wages and lax labor standards make foreign production more profitable. Nike recognizes that the threat to move all or part of production abroad can be used at home to exact reductions in labor compensation (wages plus benefits). Moreover, the threat of significant job losses at Nike allows it to demand changes to labor legislation that further weaken labor. In addition to endangering jobs, wages, labor standards, and union powers, globalization also hastens the decline of social safety nets. Citing international competitiveness, the business has been able to shift the tax burden to labor. But job losses and low wages will erode this tax base, reducing governments’ ability to finance welfare programs (Greaver, 2000; Korzeniewicz, 2003).

Problems and Opportunities of Nike’s Global Production

The main solution to the problem of Nike’s global production is to introduce laws and regulations aimed to reduce the number of professional employees working abroad, but create a supportive working environment that allowed them to work in their home country. Nike’s transferring authority will not solve the problem, but it may leave the president without sufficient discretionary authority. That will create total havoc, in my opinion, on the negotiating ability of Nike management. For example, one might say it is an unfair trade practice for countries like Korea and Taiwan to peg their currency to the American dollar. That could be called a trade policy, though it isn’t. Those currencies should be handled in the market, not pegged in an artificial way (Kotler, and Armstrong 2008). For Nike, the deregulation of human capital movements is the second example of globalization’s negative effect on labor power and the prospects of improved employment. Under an international monetary regime of deregulated financial capital and flexible exchange rates, the inflation costs are immediately increased in any economy attempting to pursue a full employment goal unilaterally. Inevitably, market considerations come up and force the issue of whether or not the presumed need is real (Christopher, 2005). Somewhere among these ruminations, a determination needs to be made as to where the product will be produced. Unfortunately, worker efforts to improve the workplace often go unrecognized and unappreciated by Nike’s management. Even worse, Nike’s management frequently censures workers when they redesign their work in ways management has not foreseen (Schuler, 1998).

People Management (HRM)

In Asian countries, Nike creates better conditions for engineers and motivates them to stay in the home country, propose affordable housing and stable work. In the current turbulent HRM scene, several rather imposing and portentous phrases have gained currency, such as “downsizing, “restructuring the workforce,” “reengineering the corporation,” and “reinventing work” (Mentzer, 2001). All of them, as far as we are concerned, are merely euphemisms for the dynamics that have always existed in the workplace–the redesigning of work assignments in response to changes in technology, competition, workers’ innovations on the job, and the adaptations industry and workers make to evolving social requirements. What is different today is the frequency of these changes and the greater cataclysmic effect for the individuals involved. At the point where work gets done, Nike’s workers are functioning at various levels of skill and knowledge and adapting to a variety of physical, social, and environmental conditions to perform tasks to specified standards. Those tasks must be documented and understood by HR specialists so they can apply their measures, generalized tools, and consulting skills to help select workers, train them, appraise their performance, give them constructive feedback, and adapt their environments to achieve optimum productivity and worker growth. They are revealing as no checklist can be because they link the essential information that must be linked–behaviors and results (Rosow and Casner-Lotto 1998). For Nike, this is the information necessary to understand the work-doing system and manage its HR dynamics. For Nike, continuous involvement of an HR staff member to implement findings, and if feasible, to extend its application to other occupations is desirable. Although the findings may have ramifications beyond the immediate problem for which initially employed, it is wise to keep focused on the particular problem and how Nike contributes to the solution (Locke, 2007; Nike Home Page. 2009).

Ethical Implications

With government support, Nike’s employees will pursue careers to achieve stability, security, relationship with others, personal growth, and ultimately status, prioritizing these goals according to their value system. For much of the past century, when the drive for careers matured as a goal in offers of employment and vocational development, this was a very tenable and fulfilling pursuit (Cohen and Roussel 2004). For Nike, ethical implications deal with cultural sensitivity and intercultural management. Careers provided opportunities for individuals with potential and determination to aspire toward goals that enabled them to achieve comfortable economic status. Nike provided employees with dedicated cultural training programs. As the new millennium approaches, the pursuit of careers appears to be in a state of flux (Mentzer, 2001). The turmoil in the retail industry brought about by global competition and industrial consolidation has shaken the concept of stability and the idea of lifelong employment in a single occupation for a single employer. Employers are less able to offer lifelong employment in a clearly defined occupational niche. For Nike, technological change and the enormous expansion of knowledge have blurred the lines of career content. Today, it appears, nothing less than lifelong training and education is necessary to stay current let alone get ahead in a career field. It is not that the idea of pursuing a career is no longer feasible. Rather, a career–in the sense of achieving stability, security, and personal growth must be pursued differently. The primary focus of these goals has moved from the employer, industry, or profession, to the individual. At Nike, an employee can no longer rely on a career label, even a licensed one, to provide the niche of security, stability, and status. Instead an individual must be able to deliver high performance in highly changing situations (Nellore and Hines 2001; Nike Home Page. 2009).

Conclusion

The analysis of the global production chain developed by Nike suggests that current process is effective because it is based on the idea that a healthy personality grows in parallel with the 40 or so years that many people spend in their careers. In fact, work impacts on and helps to shape an individual’s personality in many ways, for better or for worse. The general direction of this development is toward a more complete, unified whole–a person who has dealt successfully with the challenges laid before him or her and has moved on to the next level of personality development. Throughout much of this growth and development, a person’s work life plays an insistent and ongoing role for Nike’s production chin. Two themes developed, trust and wholeness of an individual in the work situation, are integral to the development process. The task of Nike Corporation and the government to motivate professional staff remain at home and do not look for better pay or conditions abroad. The relationship of the buyer and seller has undergone a sea change with partners moving from adversarial to collaborative and cooperative relationships. Now-a-days, when there is a marked shifting of responsibility towards the supplier firms. The buyer-supplier relationship has evolved from adversarial roles to that of mutual collaboration, formation of strategic alliances, and partnerships. Exploration of trust and commitment has been a predominating theme in the buyer-supplier collaboration literature. The approach developed by Nike shows that flexibility and compatibility are the main criteria for modern global production and supply management.

References

Bateman T.S, Snell S. A. 2004. Management: the New Competitive landscape. 6th edn., McGaw Hill Irwin.

Christopher, M. 2005. Logistics & Supply Chain Management: creating value-adding networks. FT Press; 3 edition.

Cohen, Sh., Roussel, J. 2004. Strategic Supply Chain Management. McGraw-Hill;.

Fisher, D. 2006. Activism, Inc.: How the Outsourcing of Grassroots Campaigns Is Strangling Progressive Politics in America. Stanford University Press; 1 edition.

Greaver, M. F. 2000. Strategic Outsourcing: A Structured Approach to Outsourcing Decisions and Initiatives. AMACOM.

Korzeniewicz, M. 2003. Commodity Chains and marketing strategies: Nike and the Global Athletic Footwear Industry. In Frank J. Lechner, John Boli The Globalization Reader. Wiley-Blackwell; 2 edition Pp. 167-177.

Kotler, Ph., Armstrong. G. 2008. Principles of Marketing, 12ed, Pearson Prentice-Hall.

Locke, R. M. 2007. Improving Labor Standards in a Global Supply Chain: Lessons. Web.

Mentzer, J, T. 2001 Supply chain management, Sage Publishing.

Nellore, R. and Hines, S, M. 2001. Managing buyer-supplier relations, Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Nike Home Page. 2009. Web.

Rosow, J., Casner-Lotto, J. 1998. People, Partnership and Profits: The new labor-management agenda, Work in America Institute, New York.

Schuler, R. 1998. Managing Human Resources. Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western College Publishing.

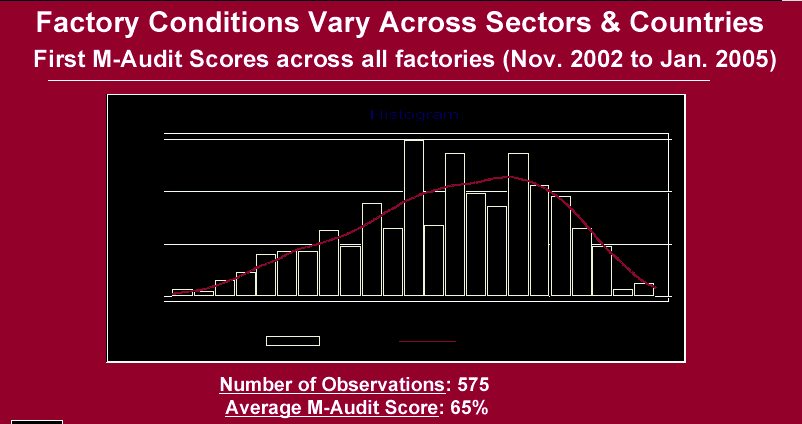

Appendix