Introduction

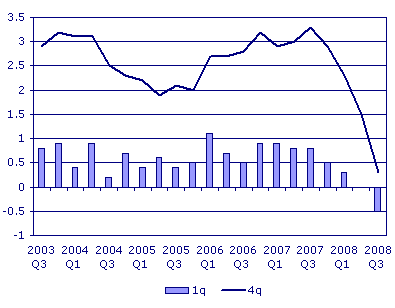

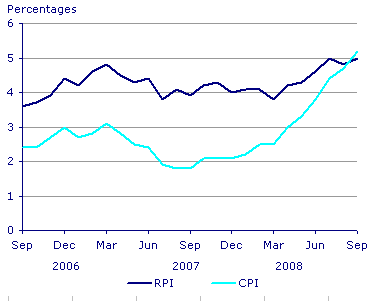

The economy of the United Kingdom (UK) started to recover in the third quarter of 1992, and in the first quarter of 2008, the UK economy went through a period of sustained economic growth, averaging 3 percent a year (Dunnell). But since 2007, the GDP growth has been declining. The major problems attributed to the decrease in GDP growth are problems in financial markets and a sharp increase in energy prices, growth fell sharply. GDP decreased by 0.5 percent in the third quarter of 2008, compared with a 0.0 percent movement in the previous quarter (ONS). Weaker service industries, construction, and production output drove the deceleration in growth This slowdown in growth has coincided with an increase in the rate of inflation, on the latest figures1 to 4.8 percent as measured by the retail prices index (RPI) in 2008 rising from 3.5 percent in 2006 and 4.7 percent as measured by the consumer prices index (CPI) in 2008 increasing from 2.5 in 2006 (ONS). Further, with the world economy going through severe financial turmoil, with financial stalwarts like Lehman Brothers filing for bankruptcy and inflation growth, the UK economy too had fallen in the downward loop. In this impending time of slowdown of the economy, the central bank and the government’s economic policies play a vital role in helping the economy to swing back to a more stable state. In this paper, we will evaluate how the Bank of England (BoE) and the Government’s policies vis-à-vis the slowdown of the economy and understand if their policies were successful or unsuccessful in framing the right macroeconomic policy

Monetary Policy

Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England, has said that this is the ‘most challenging period since the Monetary Policy Committee was set up in 1997’ (2008). But the question that arises is that what the central bank has been doing to control this downward spiral of the economy As this trend was seen since 2006? The primary objective of BoE’s macroeconomic policy was to control the following:

- To maintain price stability.

- To support the economic policy, especially policies related to growth and employment, of the government.

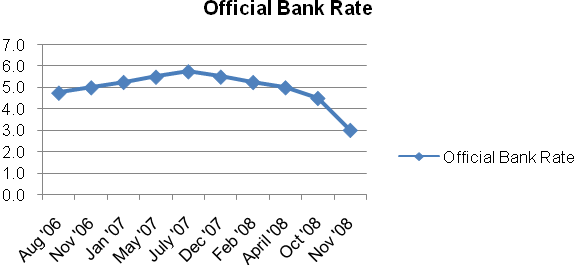

Recently BoE has announced rate cuts by 50 basis points to 3 percent from 5 percent in April 2008 (see figure 1). This is the lowest in the last two years. Initially, with the impending sign of recession over the UK economy, BoE has been reluctant to cut interest rates because inflation is at 4.4% – more than double the MPC’s government-set target of 2%. But with the continuous fall in the housing process and the consumer demand and increasing inflation but with inflation hitting the all-time high of 5.2 percent in October 2008. As the economy was facing heightened inflation expectations should have been treated as benign, given the structure of the UK labor market and the slowdown in activity that has been apparent in surveys of economic activity for the last two years. The continued weakness of wage growth confirms this view and coupled with rising unemployment and falling inflation expectations measures, it seems reasonable to assume that this risk has now passed. Clearly, BoE failed to respond to the warning signs of a looming recession and delayed cutting interest rates until it was too late to stop growth contracting and unemployment rising sharply, according to one of the nine members of its monetary policy committee. The labor market in the UK has been going through structural changes since the 1970s. The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee said that getting inflation down to the government’s 2% target remained its goal (BoE). But critics believe that the rate cut should have been brought in earlier in order to stabilize the seizing credit system.

Since 1992 the BoE has been engaged in making monetary policy based on inflation targeting. BoE delegated to set interest rates in pursuit of a preset inflation target. This policy has sufficiently helped in keeping inflation down as well as the unemployment rate in the UK but failed to bring about a structural change in the UK economy. Had the rate cuts been undertaken earlier there would have been more liquidity in the market allowing the financial market to stabilize and so the economic growth would have been stabilized. But this policy did not work in the last two years as the CPI and RPI index started rising in 2007 which showed the ineffectiveness of the monetary policy undertaken by BoE in the face of a recession.

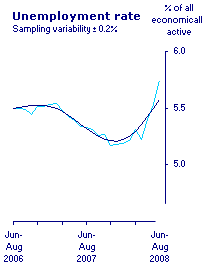

Further, in the case of unemployment (figure 3), the fixed bank rates did not curb the increasing unemployment rate. The unemployment rate was 5.7 percent for the three months to August 2008, up 0.5 over the previous quarter and up 0.4 over the year. The number of unemployed people increased by 164,000 over the quarter and by 146,000 over the year, to reach 1.79 million. The last time there were larger quarterly increases in the unemployment rate and level was in the early 1990s.

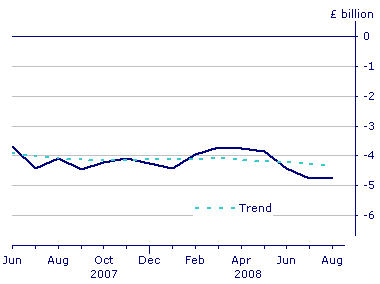

The trade deficit of the Balance of Payment (BoP) also increased as the Balance of Trade fell (see figure 4). There was a current account deficit of £11.0 billion in the second quarter of 2008, up from a deficit of £5.5 billion in the previous quarter. The second-quarter deficit was equivalent to -3.0 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) compared with -1.5 percent in the previous quarter. The higher current account deficit was a result of a fall in the surplus on the income account, which was down £6.0 billion, on the previous quarter at £4.5 billion. The main contributory factor behind the falling surplus on income account was a fall in the surplus on direct investment from £17.3 billion in the first quarter to a surplus of £14.4 billion in the second quarter and a rise in the deficit of other investment from £5.8 billion in the first quarter to a deficit of £7.5 billion in the second quarter of 2008. This is a record deficit on other investments and largely reflects a rise in net income payments made by UK financial institutions. The situation of the investment side of the economy could be controlled more effectively had the interest rates been not hold stable for the last one year.

The solution to these problems arises from a lower interest rate cut, which had been substantially delayed by BoE. It is argued a cut in interest rates would help reduce unemployment. Lower interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing encouraging spending and investment. Lower interest rates reduce the cost of mortgage payments giving homeowners more disposable income and therefore spending increases. Therefore, lower interest rates should help increase consumer spending and investment. Therefore, aggregate demand will rise, which will lead to an increase in GDP. If there is spare capacity in the economy, there will be an increase in economic growth and therefore firms will demand more workers. This will help reduce demand deficient unemployment. Had BoE cut the interest earlier in 2008 then the recession in the UK wouldn’t have taken such a serious shape.

Clearly, the problem that arose in the case of the UK is BoE and the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the UK had been concentrating on controlling the inflation rate rather than looking at the recessionary situation at hand. What the government should have done was to stimulate the economy by firstly cutting on to the public finances. The first step could be reducing the £37 billion government investment plans. Further tax rates should be controlled and not increased for an increase will cripple the economy from the consumer demand side which is already low. Further, the government failed to stimulate the private sector, which is crashing downwards rapidly. The banking regulators must stop increasing the capital demands at this weak point in the cycle. They should manage the larger banks’ liquidity and capital on a bank by bank, week by week basis, in private, allowing banks a wide range of measures to achieve and keep satisfactory capital ratios.

Fiscal Policy

Both the monetary and the fiscal policy of the UK were designed to promote economic stability by delivering low and stable inflation. The monetary framework is founded on the Government’s view that price stability is the essential foundation for high and stable levels of growth and employment, and that in the long run there is no trade-off between inflation and output and employment.

The rate cut by BoE on 6th November 2008 has been directed to combat the recessionary pressure building up on UK’s economy. The rate was reduced after the manufacturing figures showed a marked deceleration. As the main reason for the recession has been the failure of financial institutions it is expected that the rate cuts will help pump in liquidity in the market. But the market and the investors have been concerned with the size of the rate cut which was brought down from 4.5 percent to 3 percent. Though loans would become 1.5 percent cheaper, savers will be apprehensive of a lowering of savings interest rates as it will bring about a lower return on savings. But from a macroeconomic point of view, a rate cut will increase investment and may be able to recover the liquidity crunch in the market. What is required is that the banks have to be encouraged to pass most of this cut onto consumers, improving housing affordability and allowing first-time buyers to re-enter the market.

Conclusion

In the current situation, this injection of a rate cut of such a large dimension was necessary for the UK economy as the previous rate cut of 0.5 percent did not stimulate the mortgage market considerably (Butterworth). Since 2007 the economy had shown indications of an impending recession: the GDP growth fell, the inflation and unemployment rose even with inflation targeted monetary policy, and the BoP trade gap intensified. But the monetary and fiscal policymakers failed to take appropriate action to fight recession rather they concentrated o targeting inflation at 2 percent. One could argue that one outcome of the monetary and fiscal policy of BoE and the government since 2006 has been aggravating the recessionary situation and not taking corrective measures.

Bibliography

BoE. Bank of England. 2008. Web.

Butterworth, Myra. “Interest rate cut: Experts react.” The Telegraph. 2008.

Dunnell, Karen. “Measuring the UK economy: the National Statistician’s perspective.” Economic & Labour Market Review Vol. 2 No. 10 (2008): 18-29.

King, Mervyn. “Speech for Bankers and Merchants of the City of London.” Lord Mayor’s Banquet at the Mansion House. London: Bank of England, 2008.

ONS. “GDP Growth Economy decreased by 0.5% in Q3 2008.” Online National Statistics. Web.

“Inflation.” 2008. Online National Statistics. Web.