Introduction

One of the marketing strategies used by CCS Company is the application of one-on-one marketing which involves face to face interaction with individual consumers. The customer’s needs are established through asking, listening and observation. One-on-one marketing is different from other forms of marketing such as direct marketing where marketers focus on ways of saving on costs incurred in the process of reaching out to consumers (Anderson, 1982, pp 15-26). One-on-one marketing involves first of all establishing consumer core needs before focusing on the kind of products the company offers for sale. However, this method creates a friendly atmosphere between marketers and customers making them comfortable to transact any kind of business (Kondrat, 2010).

The value-added promotions could be used in cases where the focus is on building the image and retaining clients. On the other hand, value increasing promotions could be used in fulfilling short-term goals such as improving the level of sales (Chandon et al, 2000, pp. 65-81). The value-added promotion technique is mostly used in highly competitive marketplaces. Other methods of marketing may not be cost-effective to small retail chains since they do not always emphasize promotion campaigns (Chandon et al, 2000, pp. 65-81).

Marketing Communication tools

The differences between consumer and B2B marketing are well documented (Simkin, 2000). Fletcher Keith and Hart Susan (1990), who are marketing specialists, identified that B2B organizations have a tendency of not employing marketing directors, and also people in senior positions bear the responsibility for marketing. They suggest that the B2B sector has not embraced the concept of marketing in the same way as the fast moving consumer goods sector with a lower level of priority given to marketing within the organizational power structure. Marketing communication tools that CCS could use in order to win new business apart from personal selling include; advertising, sales promotion, public promotions and direct marketing (Gordon, 2006; Chardon et al, 2000, pp 65-81).

Marketing strategies to be applied should be first of all tested by the use of selected measures in order to establish their effectiveness. Every activity within the company depends on the already set goals. The controls could enable the establishment of the company’s progress and proper implementations of the right plans. The knowledge about current customers reveals preferences and buying patterns together with customers’ physical contacts which include phones numbers (Kondrat, 2010).

These details could enable marketers to easily reach the desired customer with the right products. This facilitates close relationships enabling easy satisfaction of customer needs. The issue of differentiating consumers enables the marketers to know the purchasing power of customers making identification of customers by their needs possible. Selection of the best customers could reinforce effective communication as well as the relationship between marketers and customers. Then finally there is the issue of improving the quality of goods in accordance with consumer preferences (Kondrat, 2010).

Advertising is a non-personal presentation that involves the promotion of goods and services for the purposes of increasing sales. CCS should use advertising through media like the use of television, newspapers, magazines and the Internet. The highly visible nature of advertising has got a central function in the development of the brand image. This is because it passes a strong message to the consumers on the functional abilities of the brand while at the same time pervading the brand with aesthetic meaningful values that are of relevance to the consumers (Kondrat, 2010).

Different sales promotion techniques could be used by CCS some of which include 2 for 1, price-off loyalty programs, coupons and the use of rebates. These are all aimed at increasing sales and improving the loyalty to the store (Anderson, 1982, pp 15-26). Retailers tend to increase the value of their goods by changing quality, quantity or lowering the prices. On the other hand, they add the value of their goods by offering something extra while maintaining the product price. Promotions offer their targets additional benefits beyond the standard marketing mix. The enhanced mix could include an extra product, a reduced price or an added item, service or opportunity (Kondrat, 2010).

Consumers are always attached to value and would prefer to be associated over a long period with essential and beneficial products. This strategy when well-executed increases customers’ trust in the company’s products, giving the company an upper hand in market share by improving its brand image (Guo, 2002). Sales promotion could cause some positive impact since its influence tends to directly affect the consumers. Its ability to induce the customers to buy gives an immediate response to sales within the market, hence should be the most productive in the case of CSS (Fill, 2005).

The techniques applied in the consumer sales promotion could prove significant to CCS due to their ability to determine important levels of purchasing. The majority of consumers do not always focus on the brand but base their decision to buy on prices. The only method that could be applied to effectively differentiate between retailers in a competitive market is sales promotion (Chardon et al, 2000, pp 65-81). The use of price-off increases the customers’ awareness and help in developing attractiveness towards customers and at the same time help in developing a positive attitude amongst prospective buyers.

Structuring salesforce

The sales force in a business could be structured to ensure that the organization achieves high turnovers, command a sizable share of the market, create value for products and execute promptly management strategies for the dynamic markets (Zeng et al, 2003). There are two most commonly used sales force structures, Customer-oriented and Product-oriented structures (Zeng et al, 2003).

Customer oriented structure

This structure has sales staff organized by types of customers. Taking the example of Cloud Creative Solutions (CCS) organization which deals with advertising promotions for business, the sales team could be organized into a structure comprising sales team for industries, wholesalers and retailers (Zeng et al, 2003). Organizing sales force by category is another method under customer oriented structure (Zeng et al, 2003). In a magazine within the sales department, sales forces are typically organized by categories such as fashion, cosmetics, jewellery and automobile. The greatest advantage of organizing by category is that salespeople in each category become experts within that line and do not have to involve in-depth knowledge of many categories of business. It allows them to be more knowledgeable about customers’ tastes, narrow the range of a business’s competitors, create a closer relationship with customers, and be more acquainted with their assigned industry’s trends (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp 1-24).

Category assignments work better in sales organizations in which cooperation and team selling is rewarded and compensation systems are based on making a budget or involving a pool system. For example, if salespeople are paid a bonus on the basis of making a revenue budget regardless of the amount of revenue involved, then having a big revenue-producing category is not critical to a salesperson’s income (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp 1-24).

Product-oriented structure

Some sales staffs are organized by product. For example, a television network might have different categories of a sales team working at different hours like prime time and daytime sales team (Guo, 2002). Assignments given to each team depends on the category tackled or the kind of customers to be reached. However, within network cables and television, the various accounts are typically assigned through various agencies (Grönroos, 2000). In newspapers with multiple products such as the daily paper, the sales staff could be structured by product and then by category as per the product teams. When deciding on the best way to structure a sales force span of control that consists of various variables could be controlled. These variables include the nature of job, the kind of involvement the job requires experiences of the sales team members and their personality, necessary interaction, and the level of experience of the various sales managers (Guo, 2002).

Span of Control refers to the number of people reporting to the manager. This means limiting the workload of managers through delegation of duties to other departmental heads (Grönroos, 2000). Research done in this area by Graicunas indicated that seven was the maximum number of digits or ideas an average person could comfortably handle.

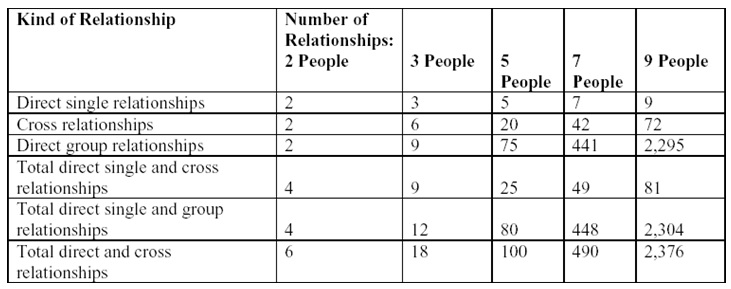

In the above table, a team comprising of one manager and two associates would involve relationships among three people. A team comprising five people would involve relationships among a manager and four other people. The other factors that would determine the sales force within the department could be significantly related to various variables which qualify each member of the team.

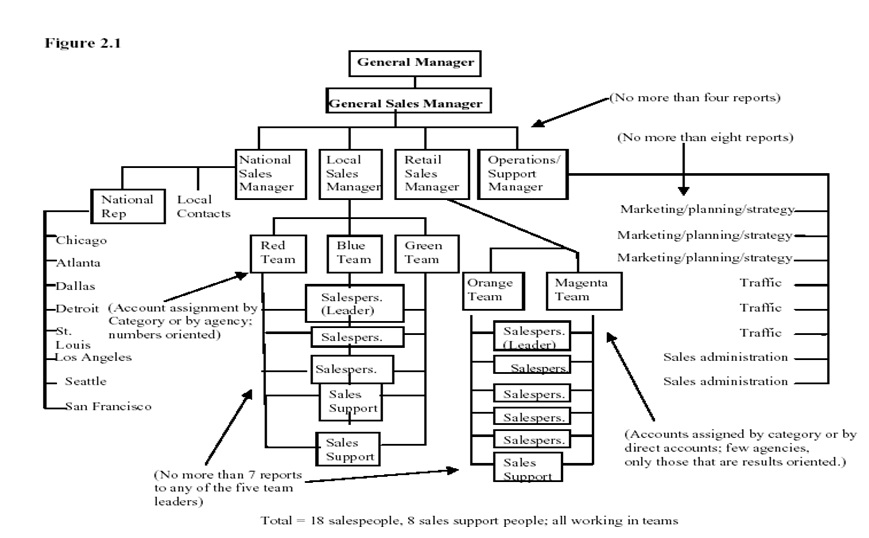

The figure above shows an example of a sales department structure that takes advantage of teams to flatten the design and limits the span of control. It could be a suitable structure for a high-rated radio station in a top-three market or a television station in a top-ten market. Also, with few changes in titles and function, the structure could work in a newspaper, cable system, national consumer magazine, or major Interactive online company. The figure indicates that there are only three managerial levels between a salesperson and the general manager and only two levels between a salesperson and the general sales manager, and those levels include team leaders (Grönroos, 2000).

The most appropriate structure for Cloud Creative Solutions (CCS) sales structure is a hybrid of both customer oriented and product oriented (Grönroos, 2000). This is because the organization needs a dedicated sales team to respond to changing demands within the market. These changes could be both within the product and new customers coming on board. This would mean that to retain and acquire a substantial market share the sales team has to incorporate the two structures. Secondly, to effectively penetrate the highly fragmented market made up of a large number of small and medium sized enterprises and several geographical regions with different needs, then both structures should be incorporated (Rosenbloom, 2007, pp. 4-9). Lastly, competition from other companies would be best countered through dedicated sales force that is competent in providing cutting edge by offering customers excellent services. This would be a necessary approach that could help the organization edge out its competitors (Grönroos, 2000).

The sales team formed has to conform to some fundamental requirements. Hunger towards achievement is essential for success and it is believed that potential teams are made out of challenges. There is also an issue of applying disciplined team basics like purpose and skills which helps in creating necessary conditions for team performance (Grönroos, 2000). The team basics should enable the sales team to utilize existing performance opportunities within the sales department. The shift from individual to team accountability is essential for the growth of the company.

Strong performance standards should be set for the sales team since according to research; companies with high and strong performance standards constitute real teams (Grönroos, 2000). This is essentially a result of management making clear performance demands based on clear objectives. A high degree of personal commitment is necessary for high performance to be realized within the sales team and this provides broader benefit to the organization (Guo, 2002).

Relationship Variables and Business networks

Mutual success in business-to-business selling often depends on establishing and maintaining a sound relationship that assists in assessing costs and benefits (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp 1-24). Relationships enable partners to perform greatly and create more value by focusing on core competencies and letting others work on their various areas of specialization. The functions of business relationships may be divided into direct and indirect functions (Walter, 2001). Direct functions produce immediate effects within the partner firms while indirect functions present oblique effects on the partners owing to their connections with other businesses (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp 1-24).

Three key attributes are used in defining partner and supplier relationships. These comprise of goal, key-value outcome measured by growth in sales revenue and communication through modern technologies as key ingredients for success (Galbreath, 2002). Within organizations, cooperative behaviour should be based upon the operation of a system of inter organizational norms. This presents a base for common understandings on ways for conducting business through the facilitation of interaction within social systems. These relationships are characterized by motives that could involve mutually compatible as well as incompatible goals (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp 1-24).

In today’s competitive global market, customers are becoming a key source of competitive advantage. In addition to revenues, suppliers should gain product ideas, technologies and market access from their customers (Walter, 2001). It means companies should consider customers as very important aspect of the business. This calls for the building of long-term and mutually beneficial and profitable relationships with the consumers. Long lasting relationships could help the establishment of high value between clients and providers as well as a competitive advantage (Walter, 2001).

Interaction presents one of the central features of the relationship framework within business markets (Medlin, 2004). Relationships always result in partnerships, joint ventures and at times strategic alliances (Donaldson and Toole, 2007). Cooperation and networking are found essential for trade associations, interlocking directorates which require joint involvement (Barringer and Harrison, 2000; Ford et al; 2003). There are two main forms of relationship the first being relationship based on a portfolio of service products majorly found in higher volume operations and secondly, personal relationships created between individual customers and employees, particularly prevalent in low-volume professional organizations (Johnson and Clark, 2008, p. 86).

The relationships might not present similar characteristics but eventually exists in wide variety of forms. Kasper et al. (2006) note that the best way through which relationships could be described is to contrast them in different dimensions. Turnbull et al. (1996) asserted that inter-organizational relationships experiences different levels of conflicts as well as cooperation. Analysing the professional services, Laing Angus and Lian Paul (2005), sociologists, distinguish different capacities of relationships within organizations. Walter 2001 identified the selling, low and high performing networking relationships.

Organizations are increasingly viewed as points where competitive advantages for modern business relationships exist (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp.1-24). However, relationships based on businesses leads to positive economic experiences (Laing and Lian, 2005). Business-to-business relationships as a complex phenomenon have multidimensional features which comprise time, structure, process, substance, function and value (Biggemann and Buttle, 2004).

Relationships are dynamic since they evolve. By providing a boundary for interaction and potential interactions, time acts as a basic ground for building business relationships (Medlin, 2004). There are different approaches to time dimensions of relationships. Some scholars highlight the cycle of relationships, others – the features of relationships. Despite the diversity of relationship development stages, all the scientists distinguish between pre-relationship and developing stages (Medlin, 2004). Relationship development might be described regarding experience, uncertainty, distance and commitment. All these features of relationships vary with time.

Concerning the structural dimension of relationships, business relationships could be described through involving recurrent characteristics which are readily exposed to outside observers (Medlin, 2004). Features such as continuity and complexity could be appropriate for the purposes of reinforcing relationship structures. Continuity is derived from the maintenance of business transactions over time, following repeated contracted steps. It focuses on the anticipation of future interaction between firms. Complexity may be given by the number, type and contact pattern of individuals involved within business relationships. A variety of ways along which relationships could be exploited for different purposes determines the level of complexity. Other features could be symmetry which is a typical situation in industrial markets and informality (Dawson, 2005).

Mutual adaptations of some kind are essential for relationships to develop as they demand coordination of activities, resources and individuals, and often reflect commitment (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp.1-24). Cooperation and conflict always form part of business relationships. This results from the need required in coping with effective strategies amidst conflicts. Each business relationship is a process through which connections between companies are created and developed involving activities, resources, and actors. These connections originate in a quasi-organization, where something unique is produced of which given otherwise, the parties involved could not effectively achieve (Wilson and Nielson, 2001, pp.1-24). The elements which connect the focal relationship are distinctive factors from which three main effects could be derived for both individual organizations and the focal relationship. The value dimension of relationships presents a significant feature and one of the reasons for companies wanting to build relationships. Value might be thought of as the difference or ratio between costs and benefits (Dwyer and Schurr, 1987).

Conclusion

Business to business marketing for CCS has several dimensions to be addressed with proper marketing tools. This should be initiated for the company to sustain its business. Without a doubt, the company has been successful in the past but this success is likely to be curtailed in the future. This is as a result of the introduction of new competitors within the market and the company quest in its expansion. The company must seek and implement well-thought strategies in their marketing operations for favourable competition in the market. Critical recommendations for the company is to immediately install a dedicated sales force that is competent in articulating the company’s objectives. Lastly, the management has to reinforce its relationships with customers, suppliers and competitors for their smooth business operations.

Reference List

Anderson, P. F., 1982, Marketing, Strategic Planning and the Theory of the Firm, Journal of Marketing, vol. 46: Spring, pp. 15-26.

Barringer, B. B. & Harrison, J. S., 2000. Walking a Tightrope: creating value Through Inter-organizational relationships. Journal of management, (3), pp. 367-403.

Biggemann, S. & Buttle, F., 2004. Conceptualizing Business to Business Relationship Value. Proceedings of the 21st Industrial Marketing and Purchasing Group Conference [CDROM]. Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

Chandon, P., Wansink, B., & Laurent, G., 2000. A Benefit Congruency Framework of Sales Promotion Effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, (10), pp. 65-81.

Dawson, R., 2005. Developing Knowledge-based Client relationships. Leadership in Professional Services. (2ndEd). Burlington, Elsevier Butterwort; Heinemann.

Donaldson, B. & Toole, T., 2007. Strategic Market Relationships. From strategy To implementation. (2nd Ed). Chichester; John Wiley&Sons.

Dwyer, F.R. & Schurr, P.H., 1987. Developing buyer-seller Relationships. Journal of Marketing, (51), pp. 11-27.

Fill, C., 2005. Marketing Communications – Engagement, Strategies and Practice. Edinburgh Gate; Pearson Education Ltd.

Fletcher, K. & Hart, S. J., 1990. Marketing Strategy and Planning in the UK Pharmaceutical Industry: some preliminary findings. European Journal of Marketing, (24), pp. 55-68.

Ford, D., Gadde, L. E., Häkansson, H., & Snehota, I., 2003. Managing business Relationships. Chichester; John Wiley and sons.

Galbreath, J., 2002. Success in the relationship age: building quality relationship Assets for market value creation. The TQM magazine, (1), pp. 8-24.

Gordon, W., 2006. Out with the new, in with the old. International Journal of Market Research, 48(1).

Grönroos, C., 2000. Service Management and Marketing: A Customer Relationship Management Approach. (2nd Ed.). Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Guo, C., 2002. Market Orientation and Business Performance: A framework for Service Organizations. European Journal of Marketing, 36 (9/10), pp.1154-1163.

Johnston, R. & Clark, G., 2008. Service Operations Management. Improving Service Delivery. (3rd Ed). Edinburgh; Pearson Education Limited.

Kasper, H., Van Helsdingen, P. & Gabbot, M., 2006. Services Marketing Management. A strategic Perspective. Chichester; John Wiley& sons.

Kondrat A., 2010. One-on-one Marketing. Web.

Laing, A.W., & Lian P.S., 2005. Inter-organizational Relationship in Professional Services: towards a Typology of Service Relationships. Journal of services marketing, (1), pp. 114- 127.

Medlin, C. J., 2004. Interaction in Business Relationships: A time Perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, (33), pp. 185-193.

Rosenbloom, B., 2007. Multi-Channel Strategy in Business-to-Business Markets: Prospects and Problems. Industrial Marketing Management, (1), 4-9.

Simkin, L., 2000. Marketing is marketing – Maybe! Marketing Intelligence & Planning, (18), pp. 154-158.

Turnbull, P., Ford, D. & Cunnigham, M., 1996. Interaction, Relationships and Networks in Business Markets: an Evolving Perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, (3), pp. 44-62.

Walter, A., 2001. Value-creation in buyer seller relationships: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Results from a Supplier’s Perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 30(4), pp. 365– 377.

Wilson, E. J. & Nielson, C. C., 2001. Cooperation and Continuity in Strategic Business Relationships. Journal of Business to Business Marketing, (8), pp. 1-24.

Zeng, Y. E., Wen, H. J., & Yen, D. C., 2003. Customer relationship management (CRM) in business-to-business (B2B) e-commerce. Information Management & Computer Security, 11(1), pp. 39-44.