Introduction

Organizational change is defined as both the process that transforms a company’s aspects, such as work practices, technology and others and the effects that the change has on the company. Stouten, Rousseau and de Cremer (2018) name the following factors that may drive organizational change if paid proper attention to new consumer expectations, governmental laws, evolving technology and economic changes. Health care is the sector where change is a constant; moreover, it is a necessary prerequisite for serving populations that undergo demographic shifts and confront new public health issues (Nilsen, Seing, Ericsson, Birken & Schildmeijer, 2020). Still, as reported by Nilsen et al. (2020), 70% of efforts to introduce organizational changes fall flat.

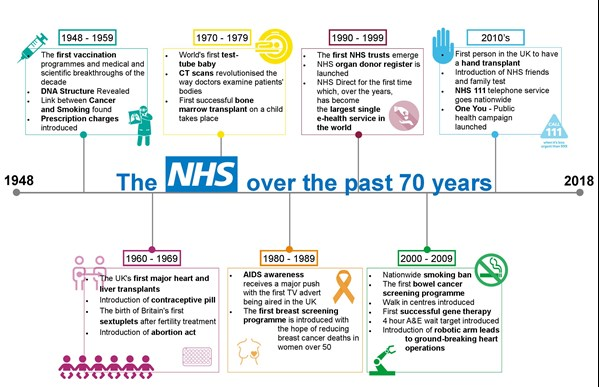

The history of the National Health Service (NHS) organization began in 1948. The creation of the organization was revolutionary on its own as back then no other country offered free healthcare on the basis of citizenship rather than fees or insurance payments (Welch, 2018). The positive changes would not have been attained if it had not been for people working for the NHS. While in 1948, the NHS hired 68,000 doctors and 11,000 nurses, by 2018, the numbers had reached 217,000 and 115,000 respectively (Welch, 2018).

These trends demonstrate how medicine in the United Kingdom advanced over six decades but also how much patient needs have grown, putting an additional burden on the system. Therefore, the UK government announced a major restructuring and one of the biggest organizational changes in the history of the NHS (Welch, 2018). The 2010 reorganization was ambitious but criticized by many, which makes analyzing the case even more compelling.

Diagnosis Tool – Open System Model

A system is open when it constantly interacts with its environment and surroundings. Interaction can take many forms, be it the exchange of information, material resources, or energy in and out of the system boundaries (Ham, Lee, Kim & Choi 2015). Ham et al. (2015) argue that in democratic countries, the government continuously communicates with the environment, in particular, it takes note of citizens’ and communities’ needs and seeks ways to tend to them. Therefore, it is safe to assume that the NHS, a state organization, is an open system.

Table 1. NHS in 2010: Open System model.

Inputs

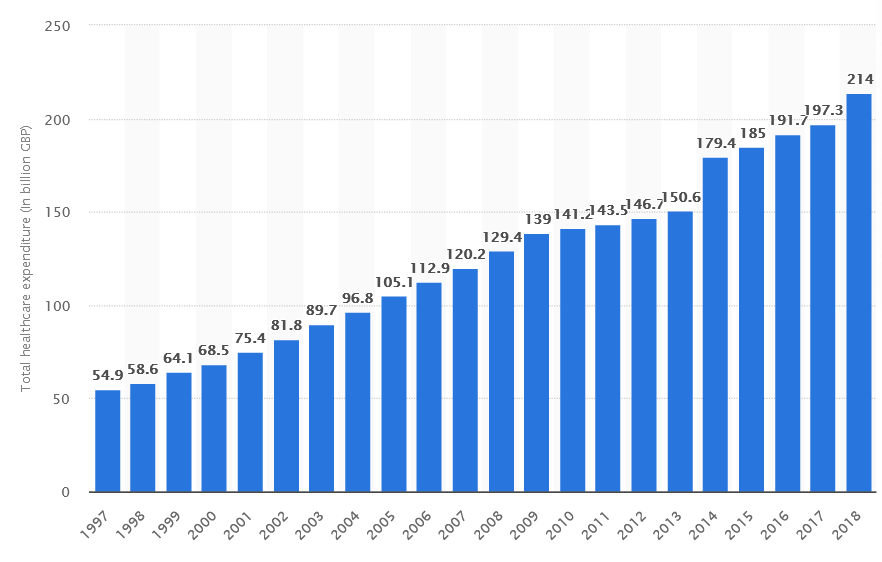

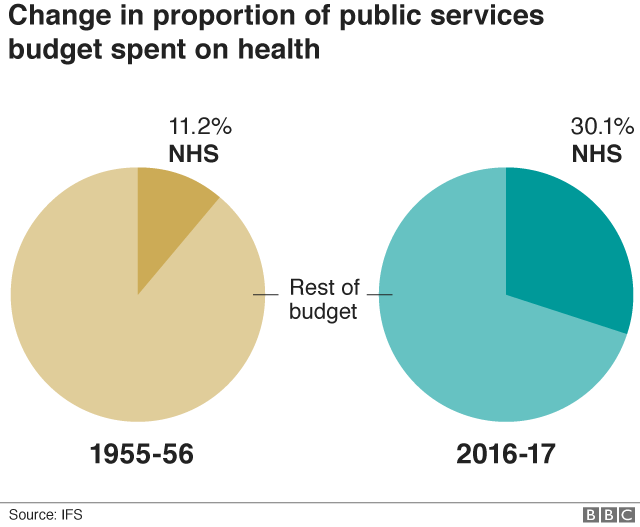

The UK population is undergoing serious demographic shifts: people were living longer than ever and having fewer children (Office for National Statistics, 2019). The aging population meant a heavier burden of age-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, cancer, osteoarthritis, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis and others (National Health Service, 2018). In response, the UK government dedicated a bigger part of the budget to cater to populations (see Image 2). In 2010, the UK spent 141 billion pounds on health expenditures, which was two billion up compared to the previous year and a twofold increase (from 70.1 billion pounds) compared to ten years ago (see Graph 1).

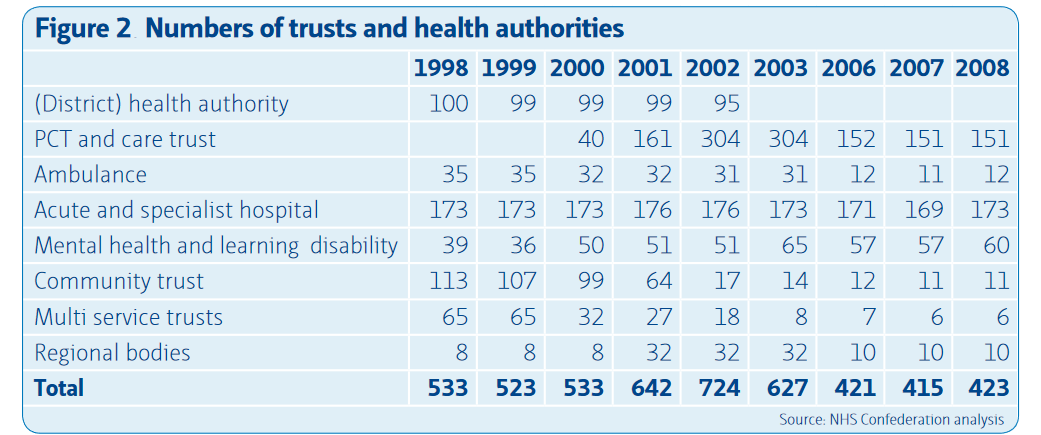

However, the health report by Hutt and Gilmour (2010) revealed the unequal distribution of funding between regions, meaning that underserved populations were still not benefitting from budgetary improvements. In the meantime, primary care trusts (PCT) had been one of the most stable types of NHS organizations during the decade (see Table 1) (Edwards, 2010). The Commons Health Committee found that they failed to fulfill their duties while having control over 80% of the healthcare budget (Mandal, 2010).

Transformation

A traditional functional bureaucracy underwent a massive structural transformation. Previously, the regional NHS providers had a centralized structure with an ever-growing number of managers, but in 2010, the number was cut down to a small Clinical Commissioning Group of approximately 40 general practitioners (GPs), a few clinicians and 15 managers. The new changes were expected to provide an incentive for GPs to interact with local communities and identify individual and group patient needs. CCGs had to engage and collaborate with local county councils, community groups and voluntary organizations. Besides, general practices were no longer separated from each other but brought to work closely toward common goals.

Outputs

CCGs became the first healthcare governing bodies to include this many practicing medical doctors, but the doctors found it difficult to assume new leadership roles. Besides, there is a risk that the lack of central budget planning has led to further fragmentation of complex healthcare services that are now commissioned separately from other services. Ham et al. (2015) express concerns regarding the coordination of primary, secondary and tertiary care. Lale and Temple (2016) found that organizational change had no effect on mortality rates across the UK. However, the researchers noticed a small improvement in male health outcomes while female patients did not benefit as much from the reorganization.

Types of Change

Ackerman (1986) distinguishes between three types of changes: developmental, transitional and transformational. Developmental change is incremental; it enhances the existing skills or processes. In contrast, transitional change is based on the premise that there is a known desired state that is different from the current state. The most radical type of change is transformational as it leads to the emergence of an organization that displays significant differences in terms of structure, processes, culture and strategy. Transformational change may lead to entering the developmental mode, in which the company constantly learns, improves and adapts. Based on Ackerman’s typology, in 2010, the NHS set out on a transitional change in which defining structures had to be altered completely.

Organisational Culture

Organisational culture can be defined as a set of expectations, values and beliefs held by a particular organization. It is an organizational culture that guides member behavior, defines the future trajectory and shapes both inner workings and communication with the outside world. Organizational culture is a broad concept that is difficult to fully operationalize; moreover, its measures may differ from sector to sector. Gershon, Stone, Bakken and Larson (2004) found as many as 120 sub-constructs of organizational culture in the healthcare sector that they later put into four categories: leadership characteristics group, behaviors and relationships, communications and structural attributes of quality of work life.

Though the term organizational culture has been around since the 1930s, the healthcare sector embraced it only in the 1980s when there emerged the need for radical reorganizations. The organizational culture received the attention it deserved largely because its quality was proven to be tied to healthcare outcomes. To date, there are many studies demonstrating the evidence of such association. For instance, Mannion and Davies (2018) report that hospitals that committed to changing the organizational culture for two years experienced significant decreases in risk-standardized mortality rates.

De Bono, Heling and Borg (2013) concur arguing that organizational culture played a big role in infection control and prevention. Six NHS hospitals that fell under the categories of “high” and “low” performing also displayed significant differences in relations with local health economy providers, human resources policies and leadership styles (Mannion & Davies, 2018). All in all, enhanced and enforced values and beliefs translated into better patient outcomes.

Mannion and Davies (2018) explain that at the NHS, organizational culture manifests itself at three levels. Firstly, there are visible manifestations of healthcare culture through staffing and reporting practices, dress codes, reward systems and the distributions of roles and services. Visible manifestations are also the spoken established ways of approaching quality improvement and patient safety as well as handling staff concerns and patient complaints (Mannion & Davies, 2018). However, organizational culture goes beyond the verbal and the visible to include categories, such as shared ways of thinking.

They encompass values and beliefs about medical ethics, patient needs, safety and scientific evidence that inform, sustain and justify visible manifestations (Mannion & Davies, 2018). In a way, they provide a rationale for existing practices or an impetus for introducing new ones. Lastly, at the third level, people in the organization hold deep assumptions that are mostly unrecognized and unconscious. Such assumptions may include what patients want from a healthcare facility or how fellow colleagues would react to a particular situation.

Power, Politics and Conflict

Power, politics and conflict are indispensable parts of organizational culture. Power is understood as a specific person’s ability and capacity to influence others. There are multiple power typologies, but the most relevant for the present report is the one that draws a line between coercive and legitimate power. Hofmann et al. (2017) explain that coercive power is based on deterrence while legitimate power depends primarily on persuasion.

Organizations that practice coercive or “harsh” power prioritize the detection of mistakes, misconduct and unlawful behavior, which is followed by punishment. In contrast, legitimate power is “soft” in the sense that it sees expertise, information and identification as a remedy for a broken system (Hofman et al. 2017). Under legitimate power, people avoid making mistakes or breaking rules not for the fear of punishment but because they share the organization’s values and internalize them enough to follow them.

Using this dichotomy, it is safe to assume that the NHS is an organization that is based on coercive power but that is trying to move toward legitimate power. Stevenson and Moore (2019) surveyed 8,000 UK doctors and found that they consider the organizational culture at the NHS a “culture of blame and fear.” They juxtapose the existing culture to a culture of learning in which it is not a punitive measure but the exchange of information that is used to improve the system (Stevenson & Moore 2019).

One of the main critiques of the pre-2010 healthcare system was the dominant position of managers who have never studied nor practiced medicine. While the introduction of the CCGs handed a more active role to actual doctors, Ham (2014) notices that there still exists a gap between managers and clinicians. Apparently, while medicine doctors are more knowledgeable in medicine matters, they lack leadership training opportunities to smoothly transition into new roles. In other words, coercive power (managers without expertise) cannot become legitimate because those who have the desired expertise lack other necessary skills.

Any organization can be seen as political because it implies a top-down hierarchy and a clear division between leaders and followers. Though the NHS tries to position itself as a non-political organization, its structure suggests otherwise. In the 2010 NHS Confederation report, Edwards (2010) noted that some types of organizations within the NHS structure are subject to change while others remain relatively constant (see Table 1). It is easily noticeable that district health authorities ceased to exist after 2002 while regional bodies, after a short increase in numbers in 2001-2003, had lost leverage and representation by 2008. In contrast, primary care trusts (PCT) had been one of the most stable types of NHS organizations during the decade (Edwards, 2010).

However, it would be wrong to assume that longevity and stability are indicative of effectiveness. In fact, around 2010, PCTs were under attack by the Commons Health Committee which found that they failed to fulfill their duties while having control over 80% of the healthcare budget (Mandal, 2010). In particular, the report showed that PCTs did not enforce new drugs and treatment plans, poorly analyzed patient data and could not manage health providers in an adequate manner. To conclude, some bodies within the NHS were elevated above others in status, which gave them not only increased leverage but also an opportunity to abuse power.

Conflict can be defined as a state of disagreement resulting from a real or perceived dissent in values, beliefs, or expectations. It is the state of conflict that often triggers organizational change and the NHS is not an exception. There is a clash between what managers want and what employees need. Kline (2019) argues that the NHS bodies and organizations suffer from an “institutional instinct” that makes them “prefer concealment, formulaic responses and avoidance of public criticism.” The current organizational culture is not conducive to sustainable change because the staff is discouraged from voicing their concerns and managers prefer to avoid conflict at all costs. Kline (2019) adds that while new laws protect those who dare to “blow the whistle,” they do not do anything about the culture itself that suppresses employees’ voices. Indeed, no reorganization effort has any chance if the workforce is excluded from the change-making process.

Kotter’s Eight Steps

Kotter’s Eight Steps is a model developed by a Harvard Business School professor based on Lewin’s change model. It includes eight steps and hinges on the premise that skipping any of these steps compromises the success of the change. Below is the application of Kotter’s Eight Steps to the NHS’s case:

- Create Urgency. Monetary injections did not solve all issues plaguing UK healthcare (Elflein, 2020). The health report by Hutt and Gilmour (2010) revealed the unequal distribution of funding between regions, meaning that underserved populations were still not benefitting from budgetary improvements. Hutt and Gilmour (2010) also shed light on health inequalities in general practice, such as fewer screening opportunities for older and deprived populations and reduced access to healthcare for ethnic minorities. Given that now such reports are becoming more public, the increased dissemination of information will create a sense of urgency.

- Form a powerful coalition. Forming a powerful coalition in the NHS’s case may mean positioning itself within the broader network of healthcare organizations. The NHS needs to engage and collaborate with local county councils, community groups and voluntary organizations.

- Create a vision for change. From the very beginning, the 2010 NHS reorganization was criticized for the lack of clear goals and a vague strategy. Ham et al. (2015) wrote that the White Paper titled “Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS” had only fifty pages, lacked detail and did not elaborate on how the proposals would work in practice. Though the 2010 reorganization was intended to “liberate” the NHS, it still revolved around top-down decisions. Instead, the King’s Fund proposed an approach that would hinge upon “building on existing arrangements”. The need for a better approach is especially evident when taking into account international experience. The best healthcare systems arrived at their current state not only through organizational change but rather through the prioritization of quality of care and its improvement.

- Communicate the vision. The new vision should become a part of the organizational culture at different levels, starting with visible manifestations. From there, the vision should move to shared ways of thinking and deeper assumptions.

- Remove obstacles. In 2021, the NHS is facing multiple obstacles, ranging from budgeting issues to the increasing number of vacancies. Below is more elaboration on creating a better work environment at the NHS, improving budgeting methods and growing cadres from within.

- Create short-term wins. Because the change process takes a while, it is important to celebrate short-term wins that keep the workforce motivated. Employee rewards and incentives may mark the completion of each separate stage, which is explained in more detail in the next section.

- Build on the change. The 2010 reorganization cannot be the final solution to the systemic ills. It should be considered a step in the right direction and the first one out of many.

- Anchor the changes in the corporate culture. Employees should be incentivized to comply with the new plan. However, compliance should not mean obedience but rather accountability which translates into speaking up, shedding light on existing problems and not avoiding confrontation.

Employee Engagement and Incentives

People make or break a change plan, and if the said people are demoralized, unsupported and disengaged, the plan is more likely to fail. Therefore, it is not enough to put GPs and clinicians in a position of power. They have to actually be capable of carrying out their new duties and transition from a clinical to an administrative setting. As mentioned before, at the moment, the NHS is going through a leadership crisis. What could help resolve the issue is clear career tracks and leadership paths that would offer more opportunities to aspiring change leaders. For instance, at the moment the NHS has the Stepping Up program tailored specifically to meet black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) healthcare specialists (“Stepping Up program”, n.d.). The NHS could build upon this experience to introduce more programs and reach out to doctors living in remote areas and serving underprivileged communities.

Changes should be made at three levels: individual, team and organizational. Kline (2019) argues that there is a new type of leadership that would assign the highest priority to transparency and honesty. Under such leadership, whistleblowing would be considered not a treacherous act and a violation of an inter-organizational agreement but an opportunity to improve. Furthermore, Kline (2019) points out the psychological aspects of change that are often overlooked. For example, many employees are conformists because they have a deep need for acceptance and recognition. Also sometimes a likely outcome of speaking up is bullying, blackmail and pressure.

For these reasons, at the team level, the desired traits are inclusivity, clarity of purpose, a small number of agreed team objectives with regular feedback and a clear division of tasks. Lastly, at the organizational level, the NHS needs an evidence-based approach that would be more data-driven and draw on employee surveys, reports, patient data and other sources.

As for incentives, currently, the NHS does have a reward system, though it may not be yielding the desired results. Grout, Jenkins, and Pepper (2018) argue that the benchmarking system that exists at the NHS at the moment does make sense. However, what they see as problematic is the way financial incentives are tied to performance. Right now “high” performing hospitals are receiving funds and subsidies that are later spent on patients (Grout et al. 2018). For GPs, there is no incentive to improve because they never really see the benefits. Therefore, excellent performance should mean a bonus to GPs’ salaries which would keep them motivated.

Appreciative Inquiry

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is another approach toward sustainable organizational change whose main principle lies in the creation of the future as opposed to solving the past. In accordance with the anticipatory principle of AI, what people do today is determined by their vision of the future, which is why setting clear goals is a must for the NHS. Further, the principle of simultaneity dictates that the system asks itself the right questions. The NHS has long had a problem with media scrutiny that criticized “postcode lottery”, drug access restrictions, availability of equipment, surgery and other procedures and increasing waiting times (Charles, 2017).

The problem was that the NHS rarely took responsibility and responded to the criticism. Its image definitely did not benefit from an institutional culture that preferred positive information about the service to “information capable of implying cause for concern” (Kline, 2019). Starting a dialogue with the media might actually help to form the right questions moving forward. Creating truthful stories about the inner workings of the company is actually in line with the poetic principle of AI. Words that are used matter because they have the power to enliven and motivate people.

Conclusion

To conclude, nationwide changes in the healthcare sector are not only challenging but also risky because the lives of millions of people are at stake. Since its inception, the NHS has been a champion of free universal healthcare and contributed to improving essential health outcomes in the United Kingdom. However, by 2010, the NHS had been confronted with problems that could no longer be resolved without organizational change. The proposed solution was supposed to “liberate” the healthcare system and give more power to the local health economies after the abolition of bureaucratized primary care trusts.

The Open System analysis has shown that among the driving forces behind the change were demographic shifts, increases in healthcare expenditures not translating into better outcomes and healthcare inequalities. The output was far from ideal and did not indicate a pronounced positive change. Further analysis has shown that the NHS is a political structure defined by coercive power and an ongoing conflict between the levels of management. The change that must come from within is stifled by low employee morale and engagement. Therefore, moving forward is not possible without setting new, clearer goals, adjusting the strategy, launching more leadership programs and treating the workforce with more respect and integrity.

Reference List

Ackerman, LS 1986. ‘Development, transition or transformation: the question of a change in organizations, organizational development practitioner, pp. 1-8.

Charles, 2017. Read all about it: media coverage of NHS rationing. Web.

De Bono, S, Heling, G & Borg, MA 2014, ‘Organizational culture and its implications for infection prevention and control in healthcare institutions’. Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 86, no. 1, pp.1-6.

Edwards, N 2010. The triumph of hope over experience. Lessons from the history of reorganization. Web.

Elflein, J 2020. Healthcare expenditure in the United Kingdom 1997 to 2018. Web.

Gershon, RR, Stone, PW, Bakken, S & Larson, E 2004, ‘Measurement of organizational culture and climate in healthcare’, JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 33-40.

Grout, PA, Jenkins A & Propper C 2018. Benchmarking and incentives in the NHS. Web.

Ham, C, Baird, B, Gregory, S, Jabbal, J & Alderwick, H 2015. The NHS under the coalition government. Part one: NHS reform. Web.

Ham, J, Lee, JN, Kim, D & Choi, B 2015. Open innovation maturity model for the government: an open system perspective. Web.

Hofmann, E, Hartl, B, Gangl, K, Hartner-Tiefenthaler, M & Kirchler, E 2017, ‘Authorities’ coercive and legitimate power: the impact on cognitions underlying cooperation’, Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 8, p.5.

Institute for Fiscal Studies 2018. The NHS at 70. Web.

Kline, R 2019. ‘Leadership in the NHS’, BMJ Leader, vol. 3, pp. 129-132.

Lale, AS & Temple, JM 2016, ‘Has NHS reorganization saved lives? A CuSum study using 65 years of data, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 109, no. 1, pp. 18–26.

Mandal, 2010, ‘NHS Primary Care Trust Managers inefficient, says Commons Health Committee report’, News Medical Life Sciences. Web.

Mannion, R & Davies, H 2018, ‘Understanding organizational culture for healthcare quality improvement’, Bmj, vol. 363, pp. 1-4.

National Health Service 2018. Arthritis. Web.

Nilsen, P, Seeing, I, Ericsson, C, Birken, SA & Schildmeijer, K 2020, ‘Characteristics of successful changes in health care organizations: an interview study with physicians, registered nurses and assistant nurses’, BMC Health Services Research, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1-8.

Office for National Statistics 2019, Overview of the UK population: August 2019. Web.

Stepping Up program. n.d. Web.

Stevenson, RD & Moore, DE 2019. ‘A culture of learning for the NHS’, Journal of European CME, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 1613862.

Stouten, J, Rousseau, DM & De Cremer, D 2018, ‘Successful organizational change: Integrating the management practice and scholarly literature’, Academy of Management Annals, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 752-788.

St. Helen Clinical Commissioning Group n.d., NHS 70th Birthday – 5th July 2018. Web.

Welch, E 2018, The NHS at 70: a living history, Pen and Sword.