Introduction

Most farmers (or growers) in Colorado operate on a small scale and take their produce to local farmers’ markets. Unfortunately, the majority of the local restaurants are too busy to visit the local farmers’ markets or prefer not to go there due to the inability do not find everything they need. Colorado Crop to Cuisine Coop (CCC) is an organization that brings locally grown produce to local restaurants through the establishment of a buying office, complete with logistics to bring the purchased products to the restaurant. CCC was formed in 2000 to enhance marketing opportunities for a group of farmers in Northern Colorado (Pepinsky and Thilmany 1). Therefore, it mainly operates in Fort Collins areas and surrounding areas within Colorado. This firm was chosen because of its innovative ways of linking consumers to producers. Its focus is acting as a link between farmers and chefs to facilitate the sale of farm produce, which is done in an effortless process. Consequently, the firm does not employ many people but minimizes farmers’ losses attributed to the decomposition of unsold farm produce. This paper analyses the firm’s operations and reports its strengths, shortcomings, financing, marketing, organizational structure, and human resource. Managerial recommendations to help the firm to enhance its operations are also provided.

Current Position, Mission Statement, and Strategic Analysis

SWOT Analysis

The key strength for CCC is that tremendous growth in the numbers of restaurants and sales has created a large market force that has enabled CCC to thrive. The ability of CCC to bring farm produce directly to their clients’ doors enables it to compete favorably with other broadband suppliers in the area. The excellence of its products in terms of taste, freshness, and service are considered advantages by the chefs. There is minimal wastage with CCC’s products because of meticulous sorting and short distribution time (Thilmany, p. 412). CCC has enlisted several producers with heated greenhouses and cold frames to prolong the growing season for some products to ensure a constant supply.

The weaknesses of the organization are explained in terms of the challenges encountered. CCC is likely to face a number of problems due to its modus operandi. For example, providing farm produce to its clientele all year round is problematic because of inconsistencies in productivity. Increasing the diversity of commodities that they can offer is also another notable hindrance. The firm has attempted to implement joint planning endeavors with chefs to guarantee that farmers plant the right crops at the right time (Thilmany, p. 412). However, this attempt did not succeed because of the inability of chefs to commit to a meal six months ahead of time. Meeting restaurants’ requirements is also problematic because restaurants are willing to buy from CCC but do not wish to spend much time (about half their working day) sourcing different products from multiple suppliers. Another setback is the lack of full commitment to the organization by CCC members, which is demonstrated by the unwillingness to pay the membership fee.

The key opportunity for CCC is the uniqueness of their service and product diversity, which farmers consider big advantages. Farmers reported that single producers have a limited product selection. Furthermore, time constraints prevent them from visiting farmers’ markets. CCC bridge this gap through its operations. However, the full potential of farmer-chef distribution is yet to be attained. The inclusion of a chef on the Board is expected to increase the number of chefs as active participants.

Threats to CCC’s operations include limited diversity of products, low supply of some commodities, and inconvenient ordering. Some chefs also cited higher costs as an impediment. As a result, chefs in the region still use the services of national or smaller distributors to supplement purchases from CCC. Some chefs preferred buying from distributors because of a wide range of produce, uniform product specifications, and the ability to supply from storerooms within 24 hours.

Current Market Position

CCC prides itself on buying homegrown farm commodities, utilizing native knowledge of production, and expanding the agricultural industry at a local level. CCC is known to offer quality fruits that ripen on the trees or vines and taste better than produce that is injected with chemicals to induce ripening or picked before sugar levels are at their optimum.

Mission Statement

The mission of CCC is to deliver native flavor from resident farms to its clientele. This mission is achieved through two long-term goals. The first goal is to increase the number of fresh items they can offer at the levels and reliability desired by the restaurant industry. This goal is achieved by establishing designated days that products are delivered, hence attaining supply chain reliability. Another strategy is finding more members to join the cooperative to increase the volumes of major products needed by restaurants. The third strategy is looking into other varieties of core products to bridge the gap between demand and supply when current items are unavailable.

The second long-term goal of CCC is to increase the organization’s revenue. This goal is achieved by finding additional commodities that can be produced locally and sold to restaurants. The second strategy is to continue expanding the number of restaurants that could buy from them. The third tactic is to explore niche local markets with the capacity to sell homegrown products. Other approaches include putting together a marketing campaign to highlight locally grown products and reminding the masses that buying local demonstrates support for everybody involved, ensures cash circulation within the area, and boosts the local economy.

Financial Section

Smallholder farmers all over the world face challenges of low productivity, unstable prices, and restricted market access. Several organizations have emerged to bridge this gap by linking farmers to markets, which has led to growth in agribusiness, which can be described as a business segment that covers farming and commercial activities related to farming. It encompasses all the key steps needed to send a farm product to the market: production, processing, and marketing. CCC capitalizes on the marketing portion of agribusiness. Similar models are used by other farm-to-restaurant organizations while other business entities have gone a step ahead by digitizing their entire operations to provide the same services as CCC. One such organization is LocalHarvest, which has developed an online platform that connects local farms, farmers’ markets, restaurants, and food co-operatives (LocalHarvest).

Small-scale producers in Northern Colorado use farmers’ markets and community-aided agriculture as the central marketing channels. Circumstantial evidence shows that producers who make sales of $250,000 or less mainly market their produce directly through farmers’ markets (Thilmany 405). Findings by the USDA’s Economic Research Service show that approximately 90% of all farms in the U.S. are small and make $250,000 or lower in yearly sales (Thilmany 405). Therefore, there is a need to support local agriculture. About 2,863 farmers’ markets were operational with estimated sales of $306 for every client per market season.

CCC keeps 15% of the prices paid by chefs when they preorder any commodity. The institution also marks up all direct buying from the farmers’ market by the same margin. This process may happen when farmers require products that are not readily available. The 15% difference is CCC’s operating margin, which is 10% higher than the usual rate of 5% that farmers’ markets charge for sales made (Thilmany, p. 408). This additional expense is justified by the need to meet the costs of synchronizing chef orders. In some cases, the prices of commodities were adjusted upward by this margin such that chefs shoulder part of the costs of CCC’s operations. As of 2004, the sales volume and profit margin made by the organization cannot sustain the hours required to manage operations.

There is inadequate financial information for CCC to enable the analysis of trends such as debt use, liquidity, and profitability. The most recent reports by the firm show that sales made by core CCC members in 2000 varied between $100 and $13,000, corresponding to 1-20% of product sales (Thilmanyб зю 408). However, the producer who made the highest sale of $13,000 was not reliable because they could manage wholesale accounts individually. Additionally, the organization only tracks large producers with frequent sales. Therefore, it is not possible to get an accurate account of its sales or expenditure. Changes in production operations for CCC could include tracking all sales irrespective of size. Such a move would facilitate monitoring of its activities to determine its profitability. Marketing the services to more chefs beyond Fort Collins and the state of Colorado would further widen the market, increasing demand for commodities, and expanding the firm’s market share. Enlisting more producers who have specialized in the constant production of on-demand commodities would also increase the attractiveness of CCC to chefs and boost the organization’s sales.

Marketing

In the initial stages of operation, CCC maintained producer attendance at local markets, which facilitated the distribution of its products. However, after detaching from the local market, the entity needed synchronized operations and private selling activities. Nonetheless, about 25% of CAMC members still sold some of their produce through CCC after it delinked from the farmers’ market (Thilmany, p. 407). The following section describes CCC’s marketing strategies with respect to the four Ps of marketing.

Price

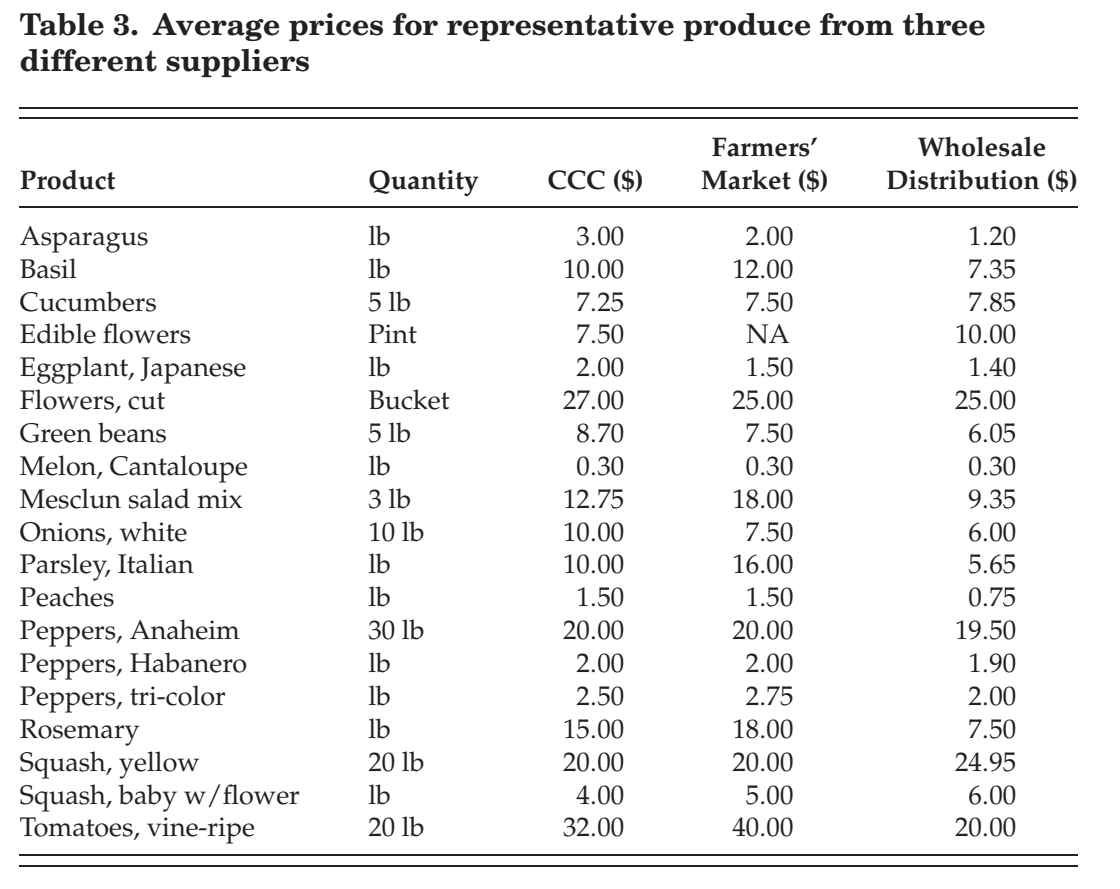

CCC’s prices are often higher than those offered at farmers’ markets and wholesale distributors. The price difference is justified by the freshness of the product and the delivery of personalized services (Thilmany, p. 408). Nonetheless, the prices of certain items such as cut flowers, melons, and summer squash are the same for all supply channels. Items with the highest demand attract premium prices because they usually run out of stock at farmers’ markets within short periods. These include mesclun salad mix and asparagus. Other items have high prices because of their apparent worth to chefs and clients at farmers’ markets, which results in competition. They include tomatoes and peaches. However, CCC still sells certain items such as edible flowers at lower prices than distributors due to challenges associated with large-scale delivery. Table 1 compares the prices of some commodities between CCC, farmers’ markets, and wholesalers. CCC was compelled to adjust its prices to match wholesalers for items such as onions and potatoes whose quality does not deteriorate significantly with time.

Product

CCC offers diverse products such as meat, honey, cheese, fruit, vegetables, mushrooms, and floral products grown in Colorado. During the 2002 season, a total of 75 different products were marketed (Thilmany, p. 408). However, 10 commodities formed more than half of the overall sales. This phenomenon mimics the product diversity of farmers’ markets where 100 different food items are sold, but only a few products in high demand form the bulk of the sales. Such products include sweet corn, fruits, and tomatoes. Tomatoes and peppers are high-demand products that are common to markets and chefs. However, other products differ substantially from the two markets. For instance, baby vegetables, herbs, and edible flowers are in high demand from chefs, whereas peaches and sweet corn are highly sought after in farmers’ markets. Conversely, wholesale distributors offer more than 300 items, which may make CCC appear limited in terms of product diversity. However, farmers report that the restricting factor is the seasonality of certain products in Colorado, notably heirloom, herbs, and baby vegetables.

Promotion

Despite the availability of numerous direct marketing openings such as farmers’ markets, producers are still in need of more channels to expand their sales portfolio. Producers within CCC concur that advertising to chefs is valuable because it supplements other goals of their venture. Marketing to chefs also aligns with the mission of various product agents, government, and not-for-profit outfits that support agriculture. Chefs from the most reliable market for their produce because of their knowledge about food items, enthusiasm, and ability to purchase in bulk. Farmers with perishable crops appreciate the buying power of chefs because it saves them vast losses during peak production. Chefs also offer markets for specialty products such as baby vegetables, herbs, and heirloom vegetables that have a low demand in the farmers’ markets. These distinctive commodities have helped farmers to advance their production know-how and local standings.

CCC markets its services and commodities mainly through word of mouth and referrals. The delivery of local farm produce to restaurant clientele increases awareness about the diversity and quality of agricultural produce in the northern part of Colorado. The interactions between farmers and chefs also help farmers to stay ahead of consumer preferences (Thilmany, p. 412). CCC connects many restaurants to farmers and in turn, takes over the facilitation of product delivery and payments.

Place

Currently, CCC’s dealings with verified restaurant accounts happen in a weekly pattern. All contacts of the farmers are synchronized in group emails hosted by Yahoo (Pepinsky and Thilmany, p. 3). Growers submit lists containing available crops to CCC’s operations manager on Fridays. The manager puts together the list, which contains details such as prices, product variety, quantities, and names of producers, and faxes it to restaurants on Saturdays. On receiving the lists, the chefs plan their orders for the following Monday or Wednesday. The manager then harmonizes orders among farmers, gets the product from the market, and delivers to the chefs alongside payment invoices. The manager also issues farmers with invoices, collects payments from chefs, and pays the farmers every fortnight. For farmers without established accounts, physical visits or phone calls are sometimes necessary to get them to place orders.

Policy, Human Resource and/or Organization

Employment and Labor

Organizing and coordinating chefs and farmers is an uphill task because of uncertainties associated with their work. Furthermore, these entrepreneurs are used to their independence and direct management. Therefore, CCC requires the expertise of an operations manager to act as a link between farmers and chefs and coordinate its activities. However, the organization has faced several issues related to employment and labor. These problems were linked to low volumes of sales to support the recruitment of full-time staff, particularly in the 2003 season. A temporary solution to this problem was to use part-time funding to employ a quality manager (Thilmany, p. 2). However, other managerial roles were to be done by members without expecting any financial payments (in-kind).

Organization

CCC was initially structured under the Colorado Agricultural Marketing Cooperative (CAMC), which was in charge of other farmers’ markets in Fort Collins and Loveland. Having prior experience with local farmers’ markets conferred certain advantages to the organizations that operated under CAMC such as Fort Collins. Other members of CAMC had prior chef market experience. The common organizational problem that was noted was the inability to handle chef accounts effectively in the course of the production season because of intensive logistics and sales efforts that were needed (Thilmany, p. 406). Commitment to CAMC was demonstrated through an annual membership fee of $50, which was non-refundable. CCC joined CAMC in 2003 but continued to function as an independent business. Consequently, it had its own membership rules, advertising materials, and leadership organization. However, CCC retained its ties with CAMC due to its ability to facilitate the crucial point of delivery logistics for producers.

CCC is run by a Board of directors, which mainly consists of farmers who sell their produce through the organization. However, a chef was later included in the board to represent the interests of chefs and increase their participation in the program. The purpose of the board is to determine the direction of the program and regulate its activities. It consists of a president, vice-president, secretary, and treasurer (Pepinsky and Thilmany, p. 3). The board has voting and nonvoting members who play advisory roles only.

Primary Legal and Regulatory Issues

CCC follows a farmer-to-chef program model, which can be considered a form of contract farming. Details about operations are made known to both parties, including price lists and expected quality of products. The relationship between the organization and its clientele is mainly based on social networking and word-of-mouth referrals. However, given that the main agenda of the cooperation is to source and deliver food items to restaurants, the main legal issues to be considered are associated with food handling regulations. Farmers are expected to be conversant with food handling laws that apply to foodservice industries (Grover et al, p. 241). These regulations specify temperature, carriage, and food hazard safety measures.

Federal regulations that direct food handling on the farms are still being developed. However, farmers need to adhere to measures that lower the risk of food-borne contamination through good agricultural practices (GAPs), which should be documented as proof of implementation (Vaughan, p. 46). Judicious use of farm chemicals such as fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, cleaning agents, and sanitizers is advised to ensure food safety at the time of harvest. A comprehensive list of the regulatory issues that govern the operations of the organization is summarized in the Food Safety Management Act (FSMA), which consists of 7 key rules (Grover et al, p. 241). These are preventive controls for human and animal food, sanitary transportation rule, produce safety rule, intentional adulteration rule, accredited third-party verification, complying with FSMA, and foreign supplier verification rule (Norwood et al, p. 8). However, only 6 out of the 7 rules apply to the organization. The clause concerning the verification of foreign suppliers does not apply to CCC because the firm distributes local agricultural produce to restaurants within Colorado.

Conclusion

Farmers who wish to attain high profits through personal sales take their products to farmers’ markets at the peak of production. However, they often encounter losses if unable to sell all their produce, which ends up in compost piles. Chefs value fresh native ingredients and are willing to source the best ingredients for their meals. Therefore, they form the best customers for farm produce because of their willingness to form trustworthy partnerships that enable them to get quality ingredients. CCC exploits the potential restaurant market available to farmers by sourcing food items from growers and delivering them to chefs conveniently.

The key challenge faced by CCC is the inability to obtain a wide variety of items in the desired quantities due to seasthe onality of production. Another setback is the failure to sign up many chefs and growers to increase its sales volumes, which hampers its capacity to raise adequate funds to employ an operations manager on a full-time basis. These problems can be overcome by implementing the following managerial recommendations. Marketing efforts should be intensified to reach as many restaurants as possible within the region to enable farmers to increase their sales. Additional market research should be done to recognize market trends and food interests to enable growers to plan appropriately ahead of time to meet these requirements. The organization should work towards reinforcing alliances among farmers to promote their farms and establish a market force to reckon with. Given the financial issues that are attributed to low sales volumes, one person can be trained appropriately to supervise marketing, sales, and distribution for the organization. This move will help to save costs while ensuring that the firm’s operations continue smoothly.

References

- Grover, Abhay K. et al. “Food Safety Modernization Act: A Quality Management Approach to Identify and Prioritize Factors Affecting Adoption of Preventive Controls Among Small Food Facilities.” Food Control, vol. 66, 2016, pp. 241-249.

- LocalHarvest. “Buy Local from CSA Markets.” www.localharvest.org/store/. Accessed 1 May 2020.

- Norwood, Hillary E. et al. “Food Safety Resources for Managers and Vendors of Farmers Markets in Texas.” Journal of Environmental Health, vol. 82, no. 2, 2019, pp. 8-12.

- Pepins, ky, Katy, and Dawn Thilmany. “Direct Marketing Agricultural Producers to Restaurants: The Case of Colorado Crop to Cuisine.” Agricultural Marketing Report, no. 3, 2004, pp. 1-5.

- Thilmany, Dawn D. “Colorado Crop to Cuisine.” Review of Agricultural Economics, vol. 26, no. 3, 2004, pp. 404-416.

- Vaughan, Barrett. “An Educational Program on Produce Food Safety/Good Agricultural Practices for Small and Limited Resource Farmers: A Case Study.” Journal of Agriculture and Life Sciences, vol. 5, no. 2, 2018, pp. 46-50.