Executive Summary

The present analytical paper explores the journey of Uber: a successful American startup that caused disruption in the transportation industry. Founded and launched in 2010, Uber has expanded into 80 countries and built a base of more than 75 million customers since. Despite the numerous achievements and accolades, the company cannot boast a spotless history of success.

In actuality, the last few years have been marked in a scandal upon a scandal. This paper grouped the controversial incidents into three vast categories: talent management, health and safety issues, and work culture and practices. The analysis of available information shows that Uber routinely dismisses the safety of both its riders and drivers.

At the root of the cause might be the organization’s toxic corporate environment, not devoid of chaotic management and discrimination against minorities. The recent revenue losses and the soiled reputation have demonstrated the need for a systemic change, which is elaborated in the second part of this paper.

Talent management is discussed from the perspective of contextualization: the consideration of internal and external factors. Building on this, three solutions are provided: diversity training, personal initiative training, and collaboration with grassroots organizations. The second part of the change plan overviews of measures targeted at the promotion of health and safety in the workplace.

Introduction

In 2010, Uber became a sensation in San Francisco, California, as the first application that let users hail a taxi from their smartphone. Since then, Uber has grown to be a global phenomenon whose ideas spread around the planet like a wildfire. The American company has gained plenty of traction, yielded skyrocketing revenues, and given rise to similar local startups and copycats. However, in its 12 years of existence, Uber has found itself in scandals upon scandals.

The corporation was bombarded with criticism because of its controversial policies, human resource management issues, and work culture that many ex-employees and researchers have dubbed utterly toxic (Rogers, 2015). Understanding how Uber has come to be the company it is now, one needs to delve into its history full of ups and downs.

The history of Uber dates back to 2007 when Travis Calanick became a millionaire at the age of 30. The UCLA dropout and serial entrepreneur sold his startup RedSwoosh for a whopping $23 million and was looking for the next venture to immerse himself into (Hartmans & Leskin, 2019). In 2008, Calanick attended the LeWeb technology conference in Paris where he became inspired by another businessman Garett Camp’s report (Hartmans & Leskin, 2019).

Camp shared his negative experience of using a cab on a New Year’s Eve and pondered whether black car services could be more affordable and easy to use. Camp and Kalanick started collaborating and recruited Ryan Graves as a general manager through Twitter in 2009.

By 2010, the team had finally been ready to launch its product in the Bay Area. At first, Uber was charging 1.5 times more than traditional taxi services. However, for Bay Area residents, the higher price was well outweighed by the convenience of calling a cab from a smartphone. The same year, Uber received a $1.25 million seed funding round from First Round Capital, investor Jason Calacinis, Kalanick’s acquaintance Chris Sacca, and Napster co-founder Shawn Fanning (Cramer and Krueger, 2016).

A year later, Uber landed a funding of $11 million and was valued at $60 million. Investors’ support, explosive growth on the domestic market, and increasing popularity allowed Uber to go international and expand into its first forein market: France.

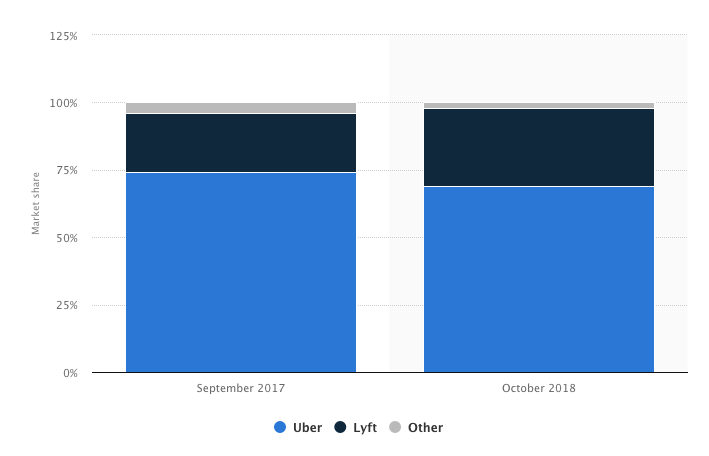

Today, it is safe to say that Uber has caused a disruption in the industry and revolutionized the way people travel. In 2018, Uber controlled 69% of the market share while Lyft came second best at 22% (see Graph 1). The global market value of the corporation has risen from $60 million in 2010 to $72 billion in 2020 (Hartmans & Leskin, 2019). Since its penetration into the French market in 2011, over the course of the next eight years, Uber conquered 80 countries (Hartmans & Leskin, 2019). As of now, 75 million people use Uber for their daily travels. The company employs three million drivers, and an average Uber employee makes $364 per month.

Despite the impressive figures, in 2020, Uber might want to tame its ambitions and uncontrolled growth and focus more on quality. In the fourth quarter of 2019, the American company generated $4 billion revenue, which is 37% more as compared to the fourth quarter of 2018 (Conger, 2019).

However, at the same time, Uber lost more in 2019 than in 2018: $1 billion vs $887 million respectively. The current CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, said that “[the company recognizes] that the era of growth at all costs is over (Conger, 2019, para. 5).” One of the many factors that seems to be hurting Uber’s standing is its human resource management issues. Like any other multinational corporation, Uber is subject to public scrutiny and criticism.

A step in the wrong direction, abuse of power, or violation of commitment quickly end up on social media and in the news. So far, Uber has faced social media campaigns, protests, and even legal charges, which is extremely threatening to the company’s reputation in the era of the heightened social awareness. The subsequent section provide an overview of Uber’s persistent HRM issues: toxic work culture, sexual harassment, poor work safety, and lack of transparency.

Human Resource Management at Uber

Driver Safety

Recent studies show that decent remuneration might not be the end-all-be-all of employees’ job satisfaction. As individuals enjoy increased work mobility and more choices on the job market, they tend to set the bar for what they expect from the employer higher than before. It has been found that 87% of employees pay attention to health and well-being offerings when choosing an employer (Martin, 2013). These offerings are not only a short-term solution for attracting more cadres.

Businesses benefit from taking care of employees’ well-being in the long term. One study shows that the average worker shows a 7% decrease in productivity due to health issues (Sliter & Yuan, 2015). If they receive adequate support, they can gain up to 15% in performance quality (Jones, Molitor & Reif, 2019). To sum up this evidence, the culture of safety attracts more employees, and, in turn, they demonstrate better performance when they are not distracted by health concerns.

Uber reports that over the last few years, it has taken the safety culture to the next level. Namely, on its official website, the multinational corporation writes that it cares about drivers as much as it cares about riders. Further, Uber enlists the measures that it has undertaken to achieve its health and safety goals. Every driver has access to the in-app emergency button that communicates the trip details to the authorities (Uber, n.d.a).

Uber customer associates are available 24/7 and respond promptly to incidents. The corporation was the first in the industry to introduce a two-way rating in which drivers can rate riders, and in case of a low rating, the latter may as well be removed from the app (Uber, n.d.a). Aside from that, Uber writes about the so-called Optional Injury Protection insurance that is supposed to help drivers in the case of an accident. In particular, the Optional Injury Protection pays disability and survivor benefits and covers medical expenses.

Despite these claims, drivers are still pretty much exposed to violence and cannot always count on the reporting system in the case of emergency. For example, just this year, an Uber driver from Southwest Atlanta was choked by a passenger and dragged out of her sedan while unconscious (Hansen, 2020).

The offenders were able to hijack the car and disappear from the scene. As the victim’s mother reported, during the fight, the driver lost her shoes and had to walk for five miles home barefoot in the middle of the night. Incidents like this prove that Uber might not be paying enough attention to collecting data on passengers’ misconduct, nor does it seem to have a system that would react instantly to accidents.

Mistreatment of Workers

This year’s global outbreak of the coronavirus has exposed the actual faultiness of Uber’s safety system. Dubal and Whittaker (2020) recount the story of Ahmed, an immigrant in San Francisco, who works for Uber and Lyft to support his family of six. Now the city has issued a “shelter in place” order and required people to stay at home to prevent the spread of the virus. Despite the order, Ahmed continues to work 60 hours a week.

He is facing a difficult choice: health risk or starvation. If Ahmed complies with the “shelter in place” order, his family will lose the sole source of income. On the other hand, working as a cab driver during the pandemic makes him vulnerable to a potentially fatal disease. As a contractor, Ahmed is not eligible for any health and unemployment benefits. Aside from that, as the man reports, he was not able to use the Optional Injury Protection mentioned in the previous paragraph when his car broke down. He had to lend money from his friends and relatives, which might be no longer an option because of the uncertainty amidst the pandemic.

Sonnemaker (2020) points out that companies like Uber and Lyft use the disguise of “technology” and “innovation” to hide their system of exploitation of disadvantaged and largely immigrant communities. The key to their profitability lies in the fundamental mistreatment of their workers: Uber cab drivers are not employees; they are contractors.

A few months ago, the California legislature passed AB5, a document that prevents companies from exploiting workers by treating them as independent contractors. Now for a company, to hire an independent contractor, it needs to assign them tasks that are different from the said company’s core business activities. As one can readily conclude, Uber violates the legislation because cab drivers are doing exactly what is central to the company’s existence.

In summation, the American company is taking advantage of the rising gig economy by forcing its contractors into a role that renders the enforcement of workers’ rights impossible (De Stefano, 2015; Hill, 2015). Because of that, workers put themselves at risk of serious health issues as well as accidents in which they will not be aided by the employer.

Talent Management

Talent attraction, retention, and management are the key responsibilities of the human resources department at any company (Harding, Kandlikar & Gulati, 2016). To say that managing professional talent is important would be a crude understatement. A quick glance at recent statistics convincingly confirms this claim.

Fatemi (2016) cites a report published by the US Labor Department that shows that one poor hiring decision can cost a company as much as 30% of the individual’s earnings in the first year of employment. Shotwell (2016) writes that 69% of companies admit that they have been negatively impacted by a bad hiring decision in the last year.

Moreover, 41% of the companies that participated in the survey said that malfunctioning hiring practices had cost them as much as $25,000 per year. Drawing on this evidence, it is safe to say that hiring mistakes are extremely costly and can have long-standing consequences.

On its official website, Uber goes into detail regarding driver screening. Namely, before a new candidate’s first trip, the company runs a background check for issues that include but are not limited to driving violations, impaired driving, and violent crime (Uber, n.d.b). Uber collects data from a variety of sources and changes its decision about an active driver if something negative resurfaces (Uber, n.d.c). Aside from that, Uber arranges annual background checks and updates information about each driver (Uber, n.d.d). Formally, the corporation seems to have thought this safety issue through, but in reality, it has not.

Since the beginning of its expansion beyond the domestic market, Uber has been failing to properly manage cadres in operating countries. In 2014, a serial sex offender, Shiv Kumar Yadav, became an Uber driver in India. After several female passengers came forward and spoke up about sexual assault and abuse, the man was charged with rape and sentenced to life in prison (Burke, 2014).

By that time, Uber had been operating in eleven Indian cities and allegedly applying the same safety standards as in other countries. Yet, at the time of the attack, the rapist was facing four criminal charges. The case of Shiv Kumar Yadav caused a massive uproar, to which the head of the Delhi transport department responded with a temporary ban of Uber within the city.

One might have presumed that that situation has pushed Uber to enforce stricter safety standards outside the US market. Right after the 2014 incident, the CEO Kalanick made a statement: “We will do everything, I repeat, everything to help bring this perpetrator to justice and to support the victim and her family in her recovery (Wong, 2017, para. 4).”

However, when in 2017, another Indian woman suffered from sexual abuse at the hands of an Uber driver, the way that the corporation treated her was far from fair. As Wong (2017) reports, the victim said that she felt violated for the second time when the Uber executives cast doubt on the credibility of her evidence.

Alexander, who was the president of business for Uber Asia Pacific at the time, traveled to India and obtained the assaulted woman’s private medical records. He theorized that the victim must be lying as a part of a conspiracy to damage Uber’s reputation. Subsequently, Alexander was fired, and Uber issued another statement, where it said that “[it was] truly sorry that she’s had to relive it over the last few weeks (Wong, 2017, para. 10).” Once again, Uber mishandled a rider safety case, apologized, and made a promise without backing it up with feasible measures.

Surely, one may argue that these two cases are anecdotal and not part of a bigger trend. However, based on Uber’s first yearly safety report issued in 2019, this would be a wrong assumption. Vittert (2019) analyzes the said report and points out that the company logged 5,981 sexual assault cases over one year period. Moreover, the safety report contained 464 rape cases, which is quite alarming (Uber, 2019). Further, Vittert (2019) writes that the media might have blown these statistics out of proportion.

If one takes into account the total number of taxi rides made with Uber, those where rape or sexual assault were a minority: around 0.0002%. Yet, in London, Uber was banned due to “poor social responsibility (Butler & Topham, 2017, para. 5).” Among other things, it was revealed that out of 154 rape allegations made in London in 2016, 32 were against Uber drivers (Butler & Topham, 2017). Drawing on these conflicting pieces of evidence, the question arises exactly what the scale of the problem is and how bad its ramifications can be.

To understand the gravity of the issue better, one should take a look at the scientific literature on the psychological effects of rape and sexual assault in victims. Mgoqi-Mbalo, Zhang, and Ntuli (2017), as well as Chaudhury et al. (2017), show that sexual assault and rape are associated with depression and PTSD (post-traumatic mood disorder). Depression is a mood disorder that decreases a person’s quality of life: it causes a feeling of sadness and desperation that trumps all other emotions.

PTSD is a condition triggered by a traumatic event such as rape that might manifest itself through recurrent negative thoughts, poor self-image, distrust of the world, and other consequences. Drawing on the evidence from these studies, it is safe to assume that a single traumatic episode can incapacitate a victim and haunt them for a long time. Therefore, while it is true that dangerous rides make up a tiny fraction of all Uber rides, the tragedy that rape causes in each victim’s life is tremendous and cannot be overlooked because of the numbers.

Surely, the numerous rape cases that occur in the operating countries are not completely Uber’s fault. In actuality, some of these countries are infamous for gender violence, and for them, it is a long-standing problem. The UN Women (n.d.) reports that in India, 28.8% of women have experienced physical or sexual intimate partner violence over the course of their lives.

The country ranks 87th in the Global Gender Gap Index that overviews gender discrimination based on economic, political, education, and health criteria (The UN Women, n.d.). Other operating countries encounter similar problems as well: for instance, Mexico shows even worse sexual violence rate at 38.8% (The UN Women, n.d.).

The situation with women’s rights is aggravating, which makes women go on strikes and protests to attract authorities’ attention (“Mexican women strike to protest against gender-based violence,” 2020). Going back to Uber, it seems that the company was pursuing profits without paying regard to safety in each operating country. It did not take into account the gender dynamic, which resulted in a series of crimes against women.

Sexism and Gender Discrimination

It is true that controlling safety in remote operating countries is extremely challenging, and impacting the gender dynamics there is nigh on impossible. The only domain that Uber has full control over is the internal environment of the corporation, which is not managed properly either.

In 2017, Susan Fowler, a site reliability engineer, quit Uber and published an essay titled “Reflecting on one very, very strange year at Uber” in her personal blog (Fowler, 2017). The essay gained a great deal of traction from the media because the author revealed the previously overlooked aspects of working for Uber as a woman.

After Fowler finished her training and joined one of the teams, she started receiving suspicious messages from her new manager. The manager explained to her that he was in an open relationship with his girlfriend, and while she had already found other partners, he was struggling to do the same.

Soon it became apparent that the manager wanted to have a sexual relationship with Fowler, which she reported to the human resources department. Their response left the engineer distraught: they told her explicitly that it was not the manager’s first offense of that kind, but they did not intend to do anything about it.

The HR managers gave Fowler a choice: a) she leaves the team, and b) she stays and receives poor performance reviews because of her whistleblowing (Fowler, 2020). Fowler chose the first option and changed teams, which allowed her to meet other female engineers at Uber. After talking to them, she discovered that they had the same experiences with male coworkers. Some of them had been harassed by the same manager who harassed Fowler, but like her, they could not resolve this issue by reporting him.

Toxic Management Style

It would be wrong to say that Uber’s corporate culture is only affecting women when, in reality, its toxicity is having an adverse effect on everyone. While the point of Fowler’s essay was to showcase the gender discrimination and unsafe work environment for women at Uber, she pointed out the overall chaotic organizational structure (Lopatto, 2020).

The author wrote that the corporation tried to run multiple projects at once: some of them would be abandoned half-way through, and others – canceled abruptly. Fowler (2017) says that all engineers were in a constant limbo: they did not know what would await them tomorrow, whether the team would be dissolved or given another insane project with an unrealistic deadline.

Because of the abnormal work-life balance, Fowler requested a transfer to another subdivision of Uber, which she had the right to. For many months, the engineer was denied a transfer for obscure reasons, and in the end, the woman quit the company altogether. Typically, transfers were available based on the applicant’s performance reviews. If the reviews were positive, the person could freely join another subdivision. Fowler used her outstanding reviews as the argument for her move, but was routinely rejected for vague reasons (Fowler, 2017).

At some point, the management stated that their motivation to keep the engineer in her place was related to factors outside work on which they never cared to elaborate. Eventually, Fowler (2017) quit Uber and found another job within one week. The company lost a hardworking and driven cadre due to its murky work processes. This first-person evidence demonstrates the toxicity of Uber’s internal environment and exposes its key issues: chaotic management style and the lack of transparency.

Change Plan for Uber

Talent Management and the Creation of a Healthier Work Environment

Talent acquisition and management remain some of the fastest growing areas of academic research. Collings et al. (2015) write that in academia, talent management remains a phenomenon-based and not a theory-driven field. Yet, over the last few years, there have emerged several theories of talent acquisition and management that can be applied in the multinational context. Gallardo-Gallardo, Thunnissen, and Scullion (2019) opine that talent management does not exist in the vacuum: it is always contextual and, hence, each case should be treated individually.

Gallardo-Gallardo et al. (2019) explain that there are two levels of contextualization, both of which matter when building a talent management strategy. At the first level, a corporation needs to understand the internal context and factors such as organizational structure, its mission, and vision. At a larger level, especially when it comes to multinational enterprises, the particularities of the outer environment should be taken into consideration, such as legislation, business culture, tradition, and others.

Building on the theory of talent management contextualization, one can introduce two changes at Uber: one at the domestic subdivisions and another one in operating countries with emerging markets. The situation with Susan Fowler described in the previous section gained so much traction and caused a great deal of outrage partly because it took place in a country where feminist ideals have long led work and social politics.

Today, women account for almost 46.9% of the US workforce, with 36.6% having college degrees (Catalyst, 2019; Statista, 2019). Moreover, today, women surpass men in attending undergraduate schools: in the US, 57.7% of Bachelor’s degrees are obtained by women (Jefree, 2018). These facts imply that the context of the US work relationships favors the equality and advancement of women. Uber cannot ignore this tendency, nor can it afford to lose qualified cadres such as Fowler, who had an attractive job offer a week after her resignation.

One of the most recognized ways of putting an end to the culture of discrimination in the workplace is diversity training. Now, it is understandable that at Uber with its male-centric culture, such initiatives might be met with scepsis and indifference. Bezrukova et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analytical integration of more than 40 years of research on the efficiency of diversity training and concluded that their success is contingent on particular factors.

The researchers write that diversity training alone does not help achieve the goals: they need to be accompanied by other measures targeted at awareness and skill development. Bezrukova et al. (2016) add that the presence of women at the training also helps: in this way, male participants can better relate to the experience of real people.

Promoting gender equality and diversity in emerging countries with strong machismo traditions such as India and Mexico is much more challenging. If in the US, the dominant paradigm supports the advancement of women and minorities, many developing countries where Uber is operating at the moment do not have a blueprint or an appropriate frame of reference (Poteat et al., 2017). Typical Western diversity training can fall on deaf ears, especially when it comes to drivers from underprivileged communities that do not have an educational background to grasp complex concepts.

Campos et al. (2017) claim that, in developing countries, traditional business training shows less efficiency than personal initiative training. In the context of Uber, personal initiative training could teach overseas employees and contractors autonomy and assertion in speaking up about issues.

Jamali, Lund-Thomsen, and Jeppesen (2017) write that corporations can collaborate with grassroots organizations that are already leading the change in the country, thus, amplifying their voice and providing them with a platform. Grassroots organizations are typically more knowledgeable about the situation in the country as well as citizens’ needs and concerns.

Health and Safety Promotion and Workers’ Rights

The previous subsection has clearly shown that Uber dismisses safety issues for both drivers and riders, which can be tackled using the accident theory that ties safety and productivity together (Zwetsloot, Leka & Kines, 2017). Hopkin (2018) writes that risks can be divided into two categories: entropy risks that occur because of business degradation and residual risks that happen regardless of people’s efforts.

Within this framework, Uber can harness such entropy risks as poor driver screenings, the lack of drivers’ protection, and dismissive attitude toward work hazards. Residual factors such as road accidents, disease outbreaks, and other force majeure situations can only be minimized but cannot be completely eliminated. Hollnagel (2016) explains that taking control of entropy requires mobilization of three key factors.

- Processes (work practices) in the case of Uber can be divided into two categories: workers’ rights and safety checks. Regarding the latter, Uber might want to make their driver screenings more comprehensive, especially in developing countries where collecting information might be quite challenging. As for workers’ rights, Uber cannot turn away from the gig economy altogether but can at least introduce benefits for drivers working long-term.

- The technology aspect is tied to the work practices aspect. Uber is a startup that owns its rise to new technologies. Now is the time to make use of these technologies to serve ethical causes. One of the ways to do it could be collaborating with the governments of operating countries for collecting data on drivers to not only deny convict employment but also help detect uncaught criminals.

- Human resources (people)

The management and continuing education of cadres have already been mentioned in the previous part; however, of a special note in the context of risk management is the ABC theory of work safety. The ABC, which stands for attitude-behavior-conditions, work safety theory deals with harnessing the human factor that accounts for a great percentage of all accidents (Hollnagel, 2016). Hollnagel (2016) opines that behavior stems from attitude, or the system of values of every single person, which is why attitude is the first aspect that needs to be addressed.

Conditions demonstrate that positive behavior is rewarded, and negative behavior will not go unnoticed. The ABC training can show managers that their mistreatment of abuse cases will not be dismissed after a half-hearted apology and an official statement. Eventually, the system in place should move in the direction where ethics will cease to be a formality and become part of usual work practices.

Conclusion

The last few years at Uber have been a turmoil: the company was struggling to address the existing issues while seeing more problems piling up uncontrollably. The American startup has suffered from whistleblowers that exposed the toxic corporate environment and official bans due to the lack of corporate social responsibility. Court cases and Uber’s own official statistics have revealed that neither drivers or riders are completely safe when using the company’s services.

The situation requires the implementation of a well-balanced change plan that will focus on three domains: talent management, safety promotion, and the creation of a healthy work environment. The present paper employs the contextualized talent management theory and shows how diversity training can be applied in the context of the domestic and overseas subdivisions. Safety and health concerns are addressed using the accident theory that ties safety and productivity together.

Reference List

Bezrukova, K. et al. (2016) ‘A Meta-analytical Integration Of Over 40 Years Of Research On Diversity Training Evaluation.’ Psychological Bulletin, 142(11), 1227.

Burke, J. (2014) Uber Taxi Driver Held On Rape Charge Is Serial Sex Offender, Indian Media Claim. Web.

Butler, S. & Topham, G. (2017) Uber Stripped Of London Licence Due To Lack Of Corporate Responsibility. Web.

Campos, F., Frese, M., Goldstein, M., Iacovone, L., Johnson, H.C., McKenzie, D. & Mensmann, M. (2017). ‘Teaching Personal Initiative Beats Traditional Training In Boosting Small Business In West Africa.’ Science, 357(6357), 1287-1290.

Catalyst (2019) Women in the Workforce – United States: Quick Take. Web.

Chaudhury, S., Bakhla, A.K., Murthy, P.S. & Jagtap, B. (2017) ‘Psychological Aspects of Rape and Its Consequences.’ Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal, 2(3), 1-7.

Collings, DG, Scullion, H & Vaiman, V (2015). Talent Management: Progress and Prospects. Web.

Conger, K. (2020) Uber Posts Faster Growth, But Loses $1.1 Billion. Web.

Cramer, J. and Krueger, A.B. (2016) ‘Disruptive Change In The Taxi Business: The Case Of Uber.’ American Economic Review, 106(5), 177-82.

De Stefano, V. (2015) ‘The Rise Of The Just-in-time Workforce: On-demand Work, Crowdwork, And Labor Protection In The Gig-economy.’ Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 37, 471.

Dubbal, V. & Whittaker, M. (2020) Uber Drivers Are Being Forced To Choose Between Risking Covid-19 Or Starvation. Web.

Fatemi, F. (2016) The True Cost Of A Bad Hire — It’s More Than You Think. Web.

Fowler, S. (2020) I Spoke Out Against Sexual Harassment At Uber. The Aftermath Was More Terrifying Than Anything I Faced Before. Web.

Fowler, S. (2017) Reflecting On One Very, Very Strange Year At Uber. Web.

Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Thunnissen, M. & Scullion, H. (2019) ‘Talent Management: Context Matters.’ The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(4), 457-473.

Hansen, Z. (2020) Uber Driver choked, Dragged out of Sedan During Carjacking in SW Atlanta. Web.

Harding, S., Kandlikar, M. & Gulati, S. (2016) ‘Taxi Apps, Regulation, And The Market For Taxi Journeys.’ Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 88, 15-25.

Hartmans, A. & Leskin, P. (2019) The History Of How Uber Went From The Most Feared Startup In The World To Its Massive IPO. Web.

Hill, S. (2015) Raw Deal: How The “Uber Economy” And Runaway Capitalism Are Screwing American Workers. New York City: St. Martin’s Press.

Hopkin, P. (2018) Fundamentals Of Risk Management: Understanding, Evaluating And Implementing Effective Risk Management. London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Hollnagel, E. (2016) Barriers and Accident Prevention. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

Jamali, D., Lund-Thomsen, P. & Jeppesen, S. (2017). ‘SMEs and CSR in Developing Countries.’ Business & Society, 56(1), 11-22.

Jeffrey, T.P. (2018) Women Earn 57% of U.S. Bachelor’s Degrees—For 18th Straight Year. Web.

Jones, D., Molitor, D. & Reif, J. (2019) ‘What Do Workplace Wellness Programs Do? Evidence From The Illinois Workplace Wellness Study.’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(4), 1747-1791.

Lopatto, E. (2020) To Expose Sexism At Uber, Susan Fowler Blew Up Her Life. Web.

Mexican Women Strike To Protest Against Gender-based Violence. Web.

Martin, J. (2013) Challenge 2013: Linking Employee Wellness, Morale And The Bottom-line. Web.

Mgoqi-Mbalo, N., Zhang, M. & Ntuli, S. (2017). ‘Risk Factors For Ptsd And Depression In Female Survivors Of Rape.’ Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(3), 301.

Poteat, T. et al. (2017). ‘Changing Hearts And Minds: Results From A Multi-country Gender And Sexual Diversity Training.’ PloS one, 12(9), e0184484.

Rogers, B. (2015). ‘The Social Costs of Uber.’ University of Chicago Law Revue Dialogue, 82, 85.

Shotwell, D. (2016). The Talent Management Stats You Need To Know. Web.

Sliter, M. & Yuan, Z. (2015) ‘Workout At Work: Laboratory Test Of Psychological And Performance Outcomes Of Active Workstations.’ Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(2), 259.

Sonnemaker, T. (2020) An Uber Driver Who Got Covid-19 Couldn’t Get The Company To Cover His Promised Sick Pay Until He Called Out Its Ceo On Twitter. Web.

Statista (2019) Percentage Of The U.S. Population Who Have Completed Four Years Of College Or More From 1940 To 2019, by Gender. Web.

The UN Women (n.d.) India. Web.

The UN Women (n.d.) Mexico. Web.

Uber (n.d.a) Drive with Confidence. Web.

Uber (n.d.b) Driver Screening. Web.

Uber (n.d.c) Driving Change for Women’s Safety. Web.

Uber (n.d.d) Our Approach to Safety. Web.

Uber (2019) Uber’s US Safety Report. Web.

Vittert, L. (2019) Uber’s Data Revealed Nearly 6,000 Sexual Assaults. Does That Mean It’s Not Safe?. Web.

Wong, J.C. (2019) Disgruntled Drivers And ‘Cultural Challenges’: Uber Admits To Its Biggest Risk Factors. Web.

Wong, J.C. (2017) Woman Raped By Uber Driver In India Sues Company For Privacy Breaches. Web.

Zwetsloot, G., Leka, S. & Kines, P. (2017) ‘Vision Zero: From Accident Prevention To The Promotion Of Health, Safety And Well-being At Work.’ Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 15(2), 88-100.