Performance appraisal is essential to the victorious operation of most firms. During this process, employees are evaluated formally and informally to determine the nature of their contributions to the organization. Appraisal occurs during periods and in meetings scheduled to produce a reasoned consideration of contributions. Still, it also occurs informally as employee contributions are observed or when an evaluation is brought to the attention of others.

Performance appraisal is instrumental in helping firms and employees achieve a variety of important outcomes. These outcomes include rewards and sanctions defined by the organization, emotions experienced and knowledge gained by the employees and goals and plans developed by the organization and its members. The importance of these outcomes suggests that employees often have strong attitudes about performance appraisal.

Certainty, if negative attitudes prevail among members, performance appraisal win be unacceptable to many members, and its use may hinder rather than help achieve outcomes. Indeed, when a supervisor discusses the appraisal of a subordinate’s performance, the setting of goals for performance improvement may be difficult or impossible. This is especially true if job security, self-esteem, or pay increases are believed to be threatened by the appraisal. Nonetheless, employees desire and often seek out information about their performance. This is particularly true if employees are new to their job or are uncertain about job duties or work assignments.

Performance Appraisal Attitudes

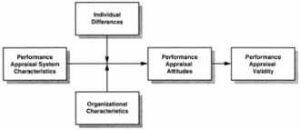

Despite the commonsense logic that attitudes about performance appraisal are crucial to its effective use, researchers only recently began to investigate the nature of these attitudes. Gabris (2001) proposed a model of the factors that affect the validity of performance ratings. Central to the model is the proposition that attitudes concerning the fairness and acceptability of the performance appraisal system are the major determinants of rating validity. In turn, these attitudes are seen as due to organizational and individual characteristics, as well as characteristics of the system itself. An adaptation of this model is shown in Fig. 1.

As conceived by Lawler (1967), characteristics of the performance appraisal system include ratter sources and the nature of the attributes that are rated by these sources. Individual differences include the incumbent’s need for feedback and the extent of the authoritarian personality. Presumably, the greater the need for feedback and the less authoritarian the personality, the more an employee would find peer and subordinate sources of performance appraisal to be acceptable. With respect to organizational characteristics, peer, self-, and subordinate ratings are seen as more acceptable in firms with a management style that encourages employees to participate in decision making.

Landy, Barnes, and Murphy (1978) were the first researchers to focus attention solely on the relation of attitudinal factors to performance appraisal. Using a single-item measure of perceived fairness and accuracy of the performance appraisal process, they identified five appraisal characteristics with regression analysis that accounted for 26% of the variance in this measure. Employees perceived greater fairness and accuracy when performance appraisal was part of a program, was done at least once a year, was based on knowledge of the employee’s performance, allowed the employee opportunity to express feelings, and led to an action plan for eliminating performance weaknesses. (Gabris, 2001)

In a follow-up study with another sample from the same organization, Landy, Barnes- Farrell, and Cleveland (1980) reported that fairness and accuracy perceptions were not related to the performance appraisal ratings received by the employees. This follow-up finding suggests that the appraisal process accounted for fairness and accuracy perceptions rather than the performance ratings. Thus, favourable attitudes about performance appraisal could not be explained simply as being due to the reception of a favourable performance rating.

Characteristics of the Performance Appraisal System

Rating Source

The immediate supervisor is the most frequently used source for performance appraisals. It is estimated that immediate supervisors generate and communicate 95% of the appraisals made in firms. However, other sources readily available in most firms include peers as well as the incumbent. Most research on attitudes about performance appraisal has focused on supervisory appraisals.

The Appraisal Interview

Perhaps the most important aspect of a performance appraisal system is the performance appraisal interview. In the interview, performance is reviewed, usually by the employee’s supervisor, and performance-related information is discussed that may affect the employee’s future work behaviour. As depicted in Fig. 2, structure and process characteristics influence outcomes from the performance appraisal interview.

The interview can serve various purposes, including discussing performance ratings, solving performance problems, setting goals, and discussing administrative decisions. Meyer, Kay, and French (1965) were the first to suggest that a single interview session should not be used to accomplish multiple purposes. They maintained that interviews focusing on employee development should be held separately from those focusing on administrative decisions.

Meyer et al. argued that the two purposes force the interviewer into two conflicting roles. The interviewer’s role for employee development requires acting as a facilitator, whereas administrative decisions require acting as a judge. An interviewer attempting to accomplish both purposes in a single session typically emphasizes administrative decisions to exclude development.

Consequently, the interviewer must deal with an employee who feels threatened about job security or pays. Meyer et al. reported improvements in employee attitudes and performance when the two roles were split into separate interview sessions. (Hall, 2007)

Other researchers have questioned the advantages of a strict separation of performance appraisal interviews by purpose. For example, motivational theory suggests that developmental goals should be linked to feedback and rewards to increase the likelihood of goal achievement. One strategy to consider is a separation of interviews based on relative emphasis. A 6-month interval could be used between an interview emphasizing employee development and another emphasizing rewards. This strategy would allow progress in solving problems and meeting goals identified in the first interview to be linked to administrative decisions made in the second interview.

Of course, more than two interviews could be conducted annually. Although research suggests that employees who are evaluated at least once a year have more favourable attitudes about performance appraisal, no guidelines are available to the optimal number of performance appraisal interviews. Very frequent interviews could be viewed as controlling and intrusive by supervisors and employees. Further research is needed on the effects of interview frequency.

The interview process has been extensively examined, and several characteristics appear to influence interview outcomes. First, employees who report more participation in the appraisal interview also report more satisfaction with the interview, more motivation to improve, and more actual improvement. Second, the support shown by the interviewer for the employee has also been linked to positive outcomes from the interview.

Interviewers are more effective when they listen to employees points of view, minimize criticisms, and acknowledge good performance. Third, solving problems that hinder employee performance has been linked to positive outcomes from the interview. Finally, mutual goal setting by the employee and interviewer is related to satisfaction with the interview, motivation to improve, and reports of actual job improvement.

Interviewing style has been used as a means to encourage employee discussion of job performance and, consequently, to obtain greater participation, minimization of threat, problem-solving, mutual goal setting, motivation to improve, and satisfaction with the interview.

The classic tripartite description reflects important variations in interviewing style. The “tell and sell” style involves informing the employee about the interviewer’s appraisal of strengths and weaknesses and then persuading the employee to follow the interviewer’s suggestions for improvement. The “tell and listen” style adds to the interview the opportunity for the employee to express feelings about the appraisal. Finally, the “problem solving” style emphasizes a nondirective discussion to encourage the employee to express ideas and feelings about strengths and weaknesses. This discussion leads to a mutual agreement about goals and plans for improving performance.

Although the interviewing style is dearly important, attributes that the interviewer brings to the interview also influence the effectiveness of the interview. An interviewer who is perceived to be credible is more likely to provide performance related information that is acceptable to the employee. Credibility can be acquired because the source is perceived to

- be an expert with respect to job performance,

- have formal power (e.g., the immediate supervisor),

- have trustworthy motives.

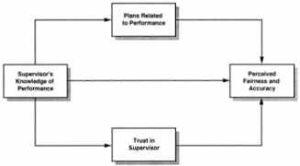

The highly sensitive nature of the appraisal interview makes employee trust in the interviewer especially critical to the acceptance of an appraisal. As shown in Fig. 3, significant direct and indirect paths were obtained from the supervisor’s knowledge of the subordinate’s performance to fairness and accuracy of appraisals. Direct paths were also obtained from trust in the supervisor and the development of action plans with the performance appraisal to fairness and accuracy.

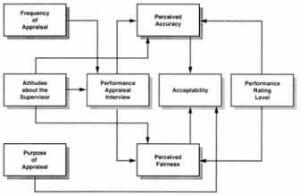

The acceptability of a performance appraisal system is determined by perceptions of fairness and accuracy, the supervisor, and the performance appraisal interview. In addition, the purpose for the appraisal and the frequency of appraisal were hypothesized to influence perceptions of the performance appraisal interview.

Hall (2007) used structural equation analysis to evaluate the hypothesized relations. The trimmed model is depicted in Fig. 4. This model suggests that the acceptability of the performance appraisal system is determined by several direct and indirect effects. Acceptability was directly influenced by perceptions of fairness and accuracy of the appraisal rating and whether the performance appraisal system was used primarily for growth and development. Acceptability was indirectly influenced by the effects that attitudes about the supervisor and performance appraisal interview had on fairness and accuracy.

Further, perceived fairness and accuracy were each directly determined by attitudes about the supervisor and appraisal interview as well as the actual performance rating. Finally, attitudes about the appraisal interview were determined by attitudes about the supervisor and the frequency of appraisal.

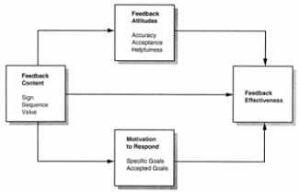

Another attribute that influences employee attitudes about performance appraisal is the content of the feedback provided by the supervisor during the appraisal, as illustrated in figure 5. The most important aspect of content is the sign of feedback. Although positive feedback is more acceptable than negative feedback, and there is research evidence that supervisors distort feedback by making it more positive, only giving positive feedback is not realistic. Many employees need improvements in their job performance.

The sequencing of feedback by its sign is a strategy for influencing attitudes about that feedback without distorting its content. A laboratory study investigated the commonsense notion that a praise first and criticize-later approach to feedback makes that feedback more acceptable to employees. It is found that a positive-negative sequence of feedback in a performance appraisal interview about the in-basket performance was perceived as more accurate than a negative-positive sequence.

Further, this sequence effect occurred only when the supervisor was perceived to have high expertise. Although these results need to be replicated in a field setting, they suggest that a praise-first approach in the appraisal interview by a credible supervisor increases the perceived accuracy and acceptance of feedback.

Another aspect of content is the specificity of feedback. The non-specific feedback in the appraisal interview, even if positive, is of little value. The information value of the feedback probably enhances the credibility of the source and leads to more favourable attitudes. More important is the response value of the feedback because it impacts the motivation to respond and ultimately on performance.

Aside from its content, feedback must be seen by the employee as helpful rather than being used to control work behaviour. Perceptions of personal control are important for attaining a sense of competence and maintaining intrinsic motivation. Thus, feedback should be given in a manner to generate feelings of accomplishment. Although no research is available, this probably requires a delicate balancing of the sign and information value of the feedback.

Individual Characteristics

Several personality theories support the notion that individuals distort performance information to maintain favourable attitudes about one’s themselves. For example, self-esteem theories propose that individuals have the need to enhance their self-evaluation and to increase, maintain, or confirm feelings of personal satisfaction, worth, and effectiveness. Self-enhancement theory assumes that people have the basic desire to think favourably of themselves and that the longer the drive is unsatisfied, the more it increases in strength.

Further, self-concept theories predict that when skills, qualifications, or abilities can be or are negatively evaluated, the self-concept is threatened. Under these conditions, protection of self-concept would be a probable reaction. In sum, performance appraisal information probably arouses desires to enhance self-esteem, think favourably of one’s self, or protect self-concept.

Self-Esteem

Although several personality variables have been related to performance feedback, little research has been reported that relates these variables to performance appraisal attitudes. Self-esteem was investigated as a correlate of subordinate reactions to their performance appraisal interviews. However, self-esteem was not related to overall satisfaction with the session or the extent to which the session was friendly, helpful, or focused on specific performance issues.

Two aspects of this research qualify the results. First, the organization had recently instituted a performance appraisal system oriented to Management by Objectives, and supervisors had been given extensive training in goal setting and conducting appraisal interviews. These organizational changes resulted in very positive attitudes about the performance appraisal. Thus, there could have been a ceiling effect on the relationships between attitudes and self-esteem. Second, the outcome of the appraisal was not controlled. Personality theories suggest that the relationships of self-esteem with attitudes about an appraisal depend on the content of that appraisal.

Age and Job Experience

These variables have been hypothesized to be inversely related to the acceptance of performance feedback. The rationale is that older and more experienced employees would have accumulated knowledge of performance standards, and they would not need feedback or find it to be acceptable.

Feedback Seeking

Finally, individuals often actively seek feedback from others about their own performance. This feedback-seeking behaviour is thought to be tied to motivations for achieving competence as well as protecting and enhancing self-esteem. According to theory, individuals differ in their history and propensity for feedback-seeking behaviour just as they differ in motivations related to competence and self-esteem. Ashford and Cummings suggest that acceptance and desire to respond to feedback is greater when the feedback is actively sought. Perhaps, individuals with a greater propensity for feedback-seeking behaviour also have more favourable attitudes about the performance appraisal.

Organizational Characteristics

Firms can do much to create a favourable context for performance appraisal. Performance appraisal should be viewed as an integral part of a manager’s organizational role. Managers should be given adequate time to make appraisals, training, and rewards for the fairness and accuracy of their appraisals. Of course, employees attach the same degree of importance to performance appraisal as they perceive being attached by their superiors. If performance appraisal has visible and continued support from all levels in the organization, employees should evaluate the appraisal process positively.

Policies

The firms should consider implementing policies that affirm employee rights in performance appraisal systems. These rights include fairness and accuracy of appraisals, privacy, use of performance standards, and supervisor competency for appraisal. The firms incorporating these rights would improve employee acceptance of the performance appraisal process. Unfortunately, no research has been conducted that directly bears on this hypothesis.

A theoretical rationale for establishing organizational policies for performance appraisal could be based on the concepts of justice developed in social psychology. Distributive justice refers to the perceived fairness of the outcomes of decision making, whereas procedural justice refers to the perceived fairness of the procedures used in decision making. Outcomes in organizational decision making include wage scales, labour-management agreements, performance appraisal ratings, and performance goals.

Processes related to these outcomes include job evaluation systems, dispute-resolution procedures, performance appraisal interviews, and Management by Objectives, respectively. Most firms already have policies concerning outcomes such as wage scales and labour-management agreements, as well as the processes of job evaluation and dispute resolution used to attain these outcomes. The perceived fairness in performance appraisal can be understood in terms of the notions of procedural and distributive justice.

Programs

Although most employees would welcome an appraisal that helps them to improve and leads to performance-based rewards, they could believe that the appraisal is based on inadequate or irrelevant information. Clearly, supervisors must be encouraged to attain first-hand knowledge of employee performance, an understanding of job duties, and the ability to conduct appraisals. Otherwise, performance appraisals would lead to few improvements and be unacceptable to employees.

Training programs have been shown to be effective for improving supervisory ability to make appraisals. Effective training should illustrate and provide practice in observing performance, recording relevant information, and making performance ratings. Training should also be provided in how to conduct performance appraisal interviews. The examined employee attitudes toward appraisal interviews were conducted by supervisors who received training in providing feedback and assigning performance goals. These training programs increased employee perceptions of the fairness, accuracy, and clarity of the appraisal interview.

In some firms, performance is constrained by factors in the work environment that are not under employee control. For example, employees may receive services and help from others to do their job, or they may have to wait for previous stages of the workflow to be completed. In these situations, performance can be impeded by poor coordination of work activities or unplanned changes in work schedules. If supervisors do not consider performance constraints in conducting appraisals, employees may believe that the appraisals are unfair and inaccurate reflections of their contributions to the organization.

The motivation of the managers who use a performance appraisal system is also critical to its acceptance. Unless managers perceive support from top management for the appraisal system, they may not be motivated to use that system. Martin (2000) described a comprehensive appraisal system, whose acceptance by managers was still in doubt after several years of operation. The system included extensive training for most levels of management, an emphasis on goal setting and development, and the splitting of salary and developmental interviews. Although the system was highly accepted by those managers who did use it, this enthusiasm did not spread throughout the organization.

Managers who did not use the system reported that they do not use it because top management had not endorsed the system. Apparently, nonusers were reluctant to engage in the time-consuming process of using the new system unless they were encouraged to do so by top management.

Early research also viewed the performance rating level as a parsimonious explanation for attitudes about the performance appraisal. The argument was that the favourability of performance appraisal attitudes could be simply due to the performance rating per se rather than the nature of the processes that determined the rating. Although the principle of parsimony is useful in model building and verification, a broader perspective includes the performance rating and process measures in a nomological network for explaining appraisal attitudes. In this way, research evidence can accumulate to help in model building and verification. The model illustrates that the level of the performance rating helps but does not solely explain attitudes about the performance appraisal.

Perhaps the single most important determinant of employee attitudes about performance appraisal is the supervisor. When the supervisor is perceived as trustworthy and supportive, attitudes about performance appraisal are favourable. Specific attitudes about performance appraisal must be viewed as tied to the general issue of supervisory effectiveness.

Supervisors often lack knowledge of their subordinates’ job duties, and they are poorly trained in providing performance feedback, gauging employee reactions to that feedback, and setting improvement goals. A focus on supervisors must also include attention to the expectations that they have for conducting performance appraisals. If supervisors believe that performance appraisal is a negative and nonrewarding endeavour, their subordinates are likely to have attitudes that match these expectations.

Another focus for research is the influence of organizational differences on attitudes about the performance appraisal. Appraisal attitudes are shaped by variables that are properly conceived at the organizational level. This level of research is difficult to conduct because it requires the sampling of firms or the sampling of distinct units in very large firms. However, attitudes about performance appraisal systems are formed in a milieu of other organizational subsystems and variables. These subsystems and variables probably shape appraisal attitudes and the usefulness of the appraisal system to a much greater degree than is currently known. (Martin, 2000)

Firms also differ in their policies about performance appraisal and the extent to which these policies are known and enforced by management. Policies can reflect that top management is serious about the importance of performance appraisal and its central role in organizational decision making. They help to foster widespread use of the performance appraisal system as well as favourable attitudes about that system. Mechanisms for establishing appraisal policies and the effects of those policies on appraisal attitudes need to be considered in future research.

Another research issue to consider is the unsettling possibility that individuals who are exposed to sophisticated appraisal systems have probably more complex appraisal attitudes. For example, in organizational settings where appraisal is done infrequently, employee attitudes are probably not well-differentiated and are strongly determined by performance-rating level. A related issue is that attitudes toward other job-related attributes probably determine the complexity of appraisal attitudes. Such possibilities suggest that models of appraisal attitudes will be exceedingly difficult to validate because they may not readily generalize across firms. Future research investigations should carefully describe the nature of the firms, performance appraisal systems, and processes under investigation.

Bibliography

Hall, L., Torrington, D. & Taylor, S. (2007), Human Resource Management, Prentice Hall.

Gabris, G. T., & Ihrke, D. M. (2001). Does Performance Appraisal Contribute to Heightened Levels of Employee Burnout? The Results of One Study. Public Personnel Management, 30(2), 157.

Martin, D. C., Bartol, K. M., & Kehoe, P. E. (2000). The Legal Ramifications of Performance Appraisal: The Growing Significance. Public Personnel Management, 29(3), 381.