Introduction

Financial globalisation is a process that cannot be reversed, and the resulting interdependence of global economies poses new challenges, not all of which can be described within the scope of economics (Aziakpono, Bauer & Kleimeier 2014). Indeed, spurred by economic and technical development, globalisation results in the clash of norms and values that constitute diverse cultures (Kline 2010; Van Meurs & Spencer-Oatey 2009). The cultural aspect of globalisation has been affecting all the features of international business. In particular, it makes cross-cultural communication important for every manager, especially one with an international assignment (Thomas & Peterson 2014, p. 211).

The problems of cross-cultural communication are typically illustrated by embarrassing etiquette blunders, that include, for example, insufficient reverence in handling the business card of a Japanese. Other cultural differences may be less embarrassing: for example, Koreans prefer to avoid negative answers, especially the word “no” (Jenkin 2014). This factor affects the process of negotiation greatly. Clever Clogs International is concerned with the cross-cultural communication challenge, and this report is aimed at describing the differences between the Netherlands and Lebanon in the terms of management-relevant cultural clashes.

The Netherlands: Relevant Facts

The Kingdom of the Netherlands is a European constitutional monarchy with a very high level of urbanisation (90% of the population is urban). The country is the eighth largest world exporter and is ranked eleven among the world importers. It is a sixth-largest EU economy that is especially concerned with transportation and trade (persistent surplus), and particular industries (chemicals, petroleum, etc.). The financial sector of the country is dominated by four commercial banks that possess about 90% of all the business assets, which makes working in the field especially challenging. The 2007 recession dealt a dire damage to the country’s economy. In 2014, a small increase of GDP allowed to hope that the country’s financial and other policies have been effective. 80% of the almost 17,000,000 population of the Netherlands are native Dutch, with no more than 5% of them being Muslim. Almost half of the population is atheistic (CIA 2015, para. 1-5). Apart from that, the country is quite open in the terms of accepting other cultures, which means that the executive is not expected to encounter discrimination of any basis (Balch 2013).

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions for Lebanon and the Netherlands

While it cannot be denied that certain management universals exist, in this report it is the difference that is highlighted (Aguinis, Joo & Gottfredson 2012). The cultural dimensions of Hofstede can be used to glean the necessary information about the values of the Netherlands.

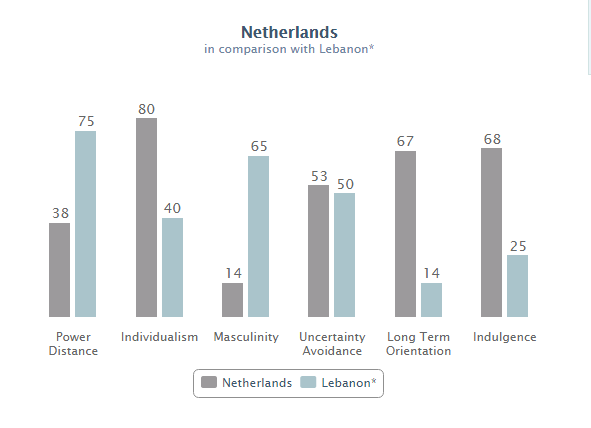

The cultural dimensions that are suggested by the Hofstede Centre (2015) include power distance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, and uncertainty avoidance as well as short/long term orientation and indulgence/restraint (Minkov & Hofstede 2011, p. 12; The Hofstede Centre 2015). The comparison of the dimensions’ scores for the Netherlands and Lebanon is shown in Figure 1.

Initially, Hofstede’s dimensions included only four parameters, but the theory was developed and changed; other dimensions, which may or may not overlap with the mentioned ones, are occasionally suggested (Minkov & Hofstede 2011; The Hofstede Centre 2015). This tendency is explained by the fact that the usage of a particular set of dimensions is defined by the aim of the cross-cultural communication. In this case, the aim is the maximisation of management practice efficiency.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions and Daily Management Practice

From the information presented in Figure 1, it is obvious that the two countries are very culturally different. It is obvious that the only dimension in which the countries have a similar score is uncertainty avoidance: both countries are moderately prone to avoid uncertainty or accept it. This parameter, among other things, defines the readiness for innovation, which Clever Clogs intends to bring along, and the Netherlands society is expected to accept change relatively well. It is obvious that the society of Netherlands is more individualistic, more indulgent and much more long-term oriented than that of Lebanon. In the terms of power distance, Lebanon demonstrates a much higher score, which means that the social inequality in the country is more prominent and is accepted as a norm. Therefore, the executive would be expected to provide a more participative management model, and the employees would be expected to be relatively more independent, goal-oriented, and pragmatic. Finally, the society of Netherlands is feminine, that is, the feminine model of behaviour (caring for others, lifting the quality of life, concentrating on happiness, not success) is a norm for the country while Lebanon’s society is explicitly masculine. Therefore, the typically feminine model of behaviour is expected from both males and females in the Netherlands, which may come as a shock to the expatriate executive but which also ensures that the executive will experience no gender-based discrimination.

Challenging Aspects of International Management

Value differences and Person-Organisation Fit

The adjustment to a new culture is a process that includes the stage of cultural shock (Thomas & Peterson 2014, p. 211). It is a natural process, and it should not discourage the executive. The support of the family and friends can be vital during this stage and should be used if possible. The value differences as described above or in any other theoretical frame often define the possibilities of person-organisation fit (Coldwell et al. 2007). Therefore, to fit in, the executive needs to pay attention to these specifics of business ethics in the Netherlands. The openness of the Netherland’s society, however, presupposes respect to cultural differences, but this aspect can affect the communication effectiveness of the executive as shown below (Balch 2013).

Negotiation and Communication

Negotiation is the feature that is most often discussed when the cultural differences are concerned (Imai & Gelfand 2010). The main challenges in this field are connected to a decrease in trust and cooperation and an increase in anxiety that characterise cross-cultural communication in comparison to intra-cultural one, which is typically mitigated by an increased cultural awareness of the participants (Imai & Gelfand 2010, pp. 83-84). This factor emphasises the importance of cultural awareness and intelligence.

Another important communication issue is the conflict management. The styles of conflict management (initially included in Thomas’ dyadic conflict model and then developed) need to be interpreted in the light of cultural differences. The dominant model of conflict management differs across cultures and the model that is effective for one society is ineffective for another one. Van Meurs and Spencer-Oatey (2009) demonstrate that the Dutch, despite their uncertainty avoidance, are not very concerned with inconvenience, which is why they do not expect the managers to avoid or neglect conflicts. Other suggested conflict management features for Dutch include the need for an open and honest communication that allows achieving the desired outcomes (Van Meurs & Spencer-Oatey 2009, p. 107).

Leadership

The leadership issues are concerned with the fact that the followers belong to another culture, and, as a result, all the aspects of leadership (for example, feedback, reprimanding, rewarding) may need careful cultural adjustment. For instance, in the Netherlands, it is suggested to emphasise individual over collective performance (without neglecting the latter) and encourage multi-source feedback from supervisors and peers (Aguinis, Joo & Gottfredson 2012).

Decision Making

The issue of ethical decision-making will always be problematic for an expatriate employee. The international law is mostly based on the principles of human rights, but even this is not sufficient to quell the clash of values and, subsequently, ethics principles (Kline 2010, p. 263). Personal decision-making can be considered a first step; apart from that, an idea has been suggested that the Netherland’s history of keeping the sea at bay affected the level of cooperation in the country, which led to the popularisation of the consensus-driven model of decision-making in the country (Balch 2013). It should be mentioned that the inclusive nature of decision-making may allow an insight into the views of the employees, which can become an appropriate asset in socially accepted and ethical decision-making.

Conclusion

The challenges of financial sector operations in the Netherlands highlight the importance of the executive’s mission, including the relevant cross-cultural management activities. The open-mindedness of the Netherland’s society presupposes that the executive will be easily accepted. Still, the vast differences between Lebanon and Netherlands, while they can be beneficial for the mission of Clever Clogs, would be expected to cause a significant cultural shock for the executive. The following points of advice can be suggested.

- Do not panic if you experience cultural shock. Try to contact the people who can offer you support and remember that this is a temporary difficulty.

- Attempt to diversify your knowledge about the Netherlands. Cultural intelligence is a crucial asset for international assignments.

- Attempt to use the features of the new employees’ attitude effectively. Their pragmatism, openness, and individualism can affect the performance of the company in a positive way; their desire to be included will help you to get accurate information about their expectations, which will help you to fit in.

Reference List

Aguinis, H, Joo, H & Gottfredson, R 2012, ‘Performance management universals: Think globally and act locally’, Business Horizons, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 385-392.

Aziakpono, M, Bauer, R & Kleimeier, S 2014, ‘Financial globalisation and sustainable finance: Implications for policy and practice’, Journal of Banking and Finance, vol. 48, pp. 137-138.

Balch, O 2013, ‘Going Dutch: why the country is leading the way on sustainable business’, The Guardian. Web.

CIA 2015, The World Factbook: Netherlands, Web.

Coldwell, D, Billsberry, J, van Meurs, N & Marsh, P 2007, ‘The Effects of Person–Organization Ethical Fit on Employee Attraction and Retention: Towards a Testable Explanatory Model’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 78, no. 4, pp. 611-622. Web.

Imai, L & Gelfand, M 2010, ‘The culturally intelligent negotiator: The impact of cultural intelligence (CQ) on negotiation sequences and outcomes’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 112, no. 2, pp. 83-98. Web.

Jenkin, M 2014, ‘Overseas clients could be as unprepared for your way of doing business as you are for theirs. Make sure you do your homework’, The Guardian, Web.

Kline, J 2010, Ethics for international business, 2nd edn, Routledge, London.

Minkov, M & Hofstede, G 2011, ‘The evolution of Hofstede’s doctrine’, Cross Cultural Management, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 10-20.

The Hofstede Centre 2015, What about the Netherlands? Web.

Thomas, D & Peterson, M 2014, Cross-Cultural Management, 3rd edn, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Van Meurs, N & Spencer-Oatey, H 2009, ‘Multidisciplinary perspectives on intercultural conflict: the ‘Bermuda Triangle’ of conflict, culture and communication’, in H Kotthoff & H Spencer-Oatey (eds), Handbook of Intercultural Communication, Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 99–120.