A Summary of Recommendations

The General Civil Aviation Authority requires an effective plan to change its current customer service and increase customer satisfaction. It is supposed that the company should have greater awareness and sensitivity regarding customers. The recommendations for improved customer service involve :

- the establishment of the Customer Service Department,

- data collection and analysis of the Customer Satisfaction Survey,

- introduction of Quick Wins program,

- training and motivation of employees;

- effective the international representation and participation,

- reengineering of service process to make it simpler,

- automation of some process in customer service;

- enhance the communication channels in which the Services are provided.

The recommendations allow one o say that though management still tends to operate from a traditional hierarchy, the company has formal processes in place for measuring performance and collecting/acting on complaints. Some companies engage in evaluating customer needs, training staff to be more proactive with customers, and/or creating teams or assigning individuals to upgrade customer services. In addition, performance-based companies more frequently compensate sales and other staff at least partially on customer satisfaction scores. Companies are strategically directed toward keeping customers, with attaining commitment and loyalty (of both staff and customers), a paramount objective (Bearden et al 23).

Appraisal of the Important Recommendations

It is assumed that the most important changes are (1) establishment of the new department, (2) employees training and motivation, (3) data collection and analysis of customer needs Since everyone in the company contributes to success through keeping customers, everyone–from the CEO to the file clerk–receives incentives and recognition based on the company’s level of customer loyalty, sales, and profits. The proposed recommendations would help the company to restructure its customer service and create a new vision of the customer and his/her needs.

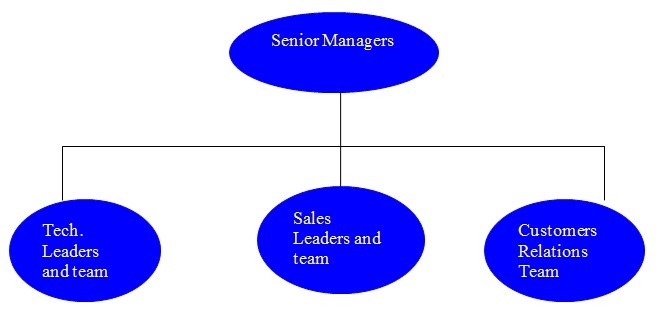

Diagram Illustrating the Existing Process

Anticipated Improvements

The long-term value strategy in GCAA is built on creating strong relationships with customers and anticipating their requirements. A significant new challenge is emerging concerning value. Companies must now strategize concerning both the physical product and the “virtual” product, such as information. Overlaps in the physical and virtual product occur in many industries, particularly those where a tangible product, such as an automobile, and an intangible product, such as service advice or computer-based information support, coexist. These relationships may be with companies that compete head-to-head (Drejer 65).

What is needed in a commitment-based customer information system is a full inventory of complaints. Unexpressed complaints should be actively gathered, if possible, whenever and wherever the company touches its customer. This, of course, also presumes that unexpressed complaints will be generated in all customer research. Complaints can be proactively elicited in any customer-provider transaction: service delivery/follow-up, sales calls, and on-site visits, to name just a few. They can be gathered qualitatively or quantitatively, by a third party or by staff, with internal, intermediate, and external customers, and with current and former customers (Perreault et al 33). They should then be combined with the expressed complaints coming from traditional sources to create a representative spectrum. This spectrum, or inventory, can be analyzed to identify the degree of impact from each area of complaint on customer loyalty. The results or deployment of complaint analysis can be either tactical or strategic. Tactically, any complaint is a red flag indicating customer unhappiness. It should be handled quickly, as positively and appropriately as possible, and at the lowest organizational level. Customer sophistication translates to providing increased value in response to the complaint and providing better training, and more empowerment, for front-line staff in dealing with the complaint, effectively and immediately (Peppers and Rogers 82)..Very often, it’s little more than room upgrades, free nights or free meals; but, the message has been delivered that the company encourages complaints and values its customers. Customer databases also afford companies the advantage and flexibility to be selective about their sales, marketing, and operations resource investments. A craft products retailer uses customer purchase history to divide its base into quintiles, according to service volume (Bearden et al 33). The data show that the top quintile, its largest purchasers, already has a very high rate of repurchase. With research, the data also reveal that these customers are giving the retailer a very high percentage of their craft product purchases. So, a loyalty-enhancing program for this first tier would not be a particularly good investment (Drejer, 21). The second tier of customers spends almost as much on craft products as the first tier; but, unlike the first tier, they are less loyal and more apt to purchase from competitors. In other words, the company has a lower share of the customer within the second quintile. So, while sales could profitably be gained from multiple quintiles, the greatest growth opportunity, in absolute dollars, comes from the second tier–not the top shoppers (Peppers and Rogers 82)…

Action Plan

Strategy 1: Establishment of the Customer Service Department

Strategy 2: Employee Training and Motivation

Strategy 3: Data collection and analysis of customer needs

Customer Service Strategies

Generating the Customer satisfaction Survey and Quick Wins program has also tackled core functions in the GCAA, and this process is still under progress. The long-term value strategy is built on creating strong relationships with customers and anticipating their requirements. A significant new challenge is emerging concerning value. Companies must now strategize concerning both the physical product and the “virtual” product, such as information. Overlaps in the physical and virtual product occur in many industries, particularly those where a tangible product, such as an automobile, and an intangible product, such as service advice or computer-based information support, coexist. The two most important components of the program are the collection and use of customer operational and performance data and the training and empowerment of staff. GCAA generates customer quality metrics (customer surveys, employee studies, training evaluation exit interviews) that are shared and applied across the company (Fill 191), They benchmark outside the company and industry for best practices, and they identify process owners to undertake improvements (Peppers and Rogers 87). Staff is given responsibility and authority to act, more so because management/approval layers have been minimized. Recognition is stressed, and staff is encouraged to make suggestions. Teamwork and cross-functionalism exist throughout the company, with the objectives of improving work processes, preventing problems, and eliminating defects and waste (Kotler and Armstrong 54).

To increase customer involvement in service provision, training programs are recommended. Performance-based companies like GCAA take a proactive approach to customers and internal processes. While management still tends to follow traditional hierarchical and bureaucratic models, inhibiting internal, horizontal communication somewhat, many of these companies have gotten closer to their customers. Methods of doing this include complaint monitoring and handling through customer service centers, segmentation of customers according to their needs, and more representative, thorough, and current measurements that track levels of company performance on key attributes and transactions. Some measurement programs also assess the importance of the attributes (Fill 34).

GCAA senior management–beyond saying they are customer-focused. and drafting mission and vision statements and periodic memos for staff–must be visible, preferably to internal, intermediate, and external customers. This creates an atmosphere of shared responsibility, commitment, and coherence for staff. In many organizations, senior management focuses entirely on strategic planning and decision-making and setting up structures and technologies. They are detached from the day-to-day, indifferent to operational issues. Implementation is left to middle managers and frontline staff. Involvement and visibility are rare. Some of this, at least in the United States, is derived from history. Our free enterprise system was built on individual effort and achievement. It is only in more recent times that interdependence, as a concept, has been seen as the more effective model for organizations. They develop a better understanding of how things work in the organization and are more receptive to process innovations, cross-functionalism, and individual and team empowerment. They set an example by being involved with the business of the company, which encourages others to learn and be proactive. Every year, for example, Disney World senior executives spend several days taking tickets or selling popcorn and hot dogs. Although Home Depot conducts extensive customer research, their president spends at least a quarter of his time in the stores talking to customers and staff. It can’t, however, be window-dressing. Executives must prepare for the experience and must share the same pressures as front-line contact staff (Bearden et al 72).

Organizational Changes

The possible problems and constraints are resistance to change and financial investments in new technology and customer support services. Companies typically have five scarce resources: people, facilities, time, money, and technology. Technology is a driving strategic force. Technology impacts speed, customization, service, quality, design, and availability and use of information. For GCAA, matrix structures flourish in an environment that is task-oriented or project-oriented, bringing together resources and sets of capabilities for a particular purpose. They have no locus of control and direction, nor do they require one. Matrix structures are particularly effective in an environment of change. Cluster structures are the least prevalent, functioning by and for the benefit of individual members. They have no center or hierarchical control. Mostly, cluster structures exist in small professional and not-for-profit service organizations (Bearden et al 72). Staff can be defined as the ability to contribute based on function and training. It has little to do with management level, or who delegates and who does not Management style is often lattice or horizontal, with a company focus on continuous improvement in all activities: understanding and serving customers, creating knowledge and information flow around customer needs, staff communication and empowerment, team process, and so forth. Performance measurement is ongoing, with improvement activity prioritized around customer retention, their intended market action, and proclivity to remain loyal. Shared values goals are the company’s set of overriding, guiding meanings, directions, and concepts–as understood by the organization and its suppliers and customers–that the organization considers significant and unique, even differentiating. It can also be the basis for corporate mission or vision, that banner which all members of the organization are expected to march behind and honor.

Benefits of the Proposed Action Plan

Front-end reactive customer data can include inquiry and complaint calls and letters, purchase histories of current and former customers, demographics, warranty/guarantee cards, and the like. Proactive data can come from third-party/staff generated qualitative and quantitative research (among potential, current, former, competitive, and internal customers), customer-supplier interaction (sales calls, advisory councils, customer training, customer visits, trade shows, telemarketing), market/benchmarking observation, staff suggestions, and so forth. At the same time, internal customer research should not be a critical or solo element of research. One major corporation uses “surrogate customer” panels of internal staff as an occasional substitute for collecting customer data. This can be very dangerous. Insofar as customer research is concerned, it should be designed to provide as much objective depth and direction as possible. Remember, this is customer value, loyalty, and retention-based research as opposed to satisfaction research. The goal is to obtain an understanding of perceptions from all relevant customer groups. Companies seeking to focus on customers can no longer afford traditional hierarchies and bureaucracies. Fiefdoms and decision-making control or information hoarding inhibit communication and cross-functionalism and create barriers to listening and cooperating, taking energy away from attention to customers. There also may be bias by the sender or receiver, information omission or distortion, overload, or lack of clarity or immediacy. Proactive networked companies also allow “communities of practice” to form, in which groups with a common value-added interest-such as customer loyalty–informally communicate and collaborate. Part social, part professional, these informal groups stimulate innovation and cross-functionalism. At the company communities of practice are identified and recognized for their abilities to listen and learn from each other, and maybe assigned specific tasks (Bearden et al 24). One such group is responsible for cross-functionally assessing microchip designs. Willingness to embrace staff diversity and empowerment and to have staff question existing processes, especially as related to customers, clearly separate marginal or good companies from excellent ones. Companies that fail to listen to internal customers or that give them insufficient opportunities to communicate and participate ultimately weaken their competitiveness and productivity. Staff is less proactive and loyal, and this is reflected in their relations with customers. However, studies by management consulting firms, marketing research polling companies, and the business press tell us over and over that the majority of employees in most companies don’t feel they make a difference. Closely related to GCAA staff communication are skills enhancement and internal and external staff empowerment. As with communication, these are areas of challenge for many companies. Staff is given insufficient cross-functional training and latitude for action, frequently because management is more concerned with keeping control (Drejer, 32).

Conclusion

The implementation of new strategies at GCAA shows that customer service, the third group having heavy customer contact, also has a largely reactive relationship with customers. Customers call in with inquiries or complaints, often on special telephone numbers. Or they call with service requests. Some may even write. Except for the “welcome letter” or welcome call or similar approach that some companies use, customers initiate the contact. With the increasing focus on optimizing customer loyalty and long-term value, the structural transformation of sales, marketing, and customer service is well underway. Companies are coming to understand that the customer simply wants a closer relationship and more value from suppliers–and makes no particular distinction as to whom in the company provides it. In commitment-based companies, sales and marketing are more actively involved in service. Customer service operates as a marketing profit center. There is more cross-functionalism, more cross-training, more cross-boundary teaming on behalf of the customers. Teams can provide sales follow-ups, enhancements, and add-ons. They can cross-sell. They can reclaim lost customers. They can survey current or lost customers and generate unexpressed (latent) complaints.

Works Cited

Bearden, W. O., Ingram, Th. N., LaForge, L.W. Marketing, Prentice-Hall, 2004.

Drejer, A. 2002, Strategic Management and Core Competencies: Theory and Application. Quorum Books, 2002.

Peppers, D., Rogers, M. Return on Customer: Creating Maximum Value From Your Scarcest Resource. Currency, 2005.

Fill, C. Marketing Communication: Contexts, Contents, and Strategies 2 and. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999.

Kotler, Ph., Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing. Prentice Hall; 11th edition, 2005.

Perreault, W.D., Cannon, J.P., McCarthy, E.J. Marketing: Principles and Perspectives. McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 4 edition, 2003.