The word innovation means a new way of doing something. It means the incremental, revolutionary, or radical changes in the products, processes, or the process in which the organization is. When we talk about the difference between innovation and an invention it is said that an invention is an idea that is turned manifested while innovation is an idea that is applied successfully. Innovation doesn’t mean that product, the process should be out of the blue but it should be significantly differentiable from the competitors. It can be applied to almost all the fields like arts, economics, business, and government policy. For the business purpose, the innovation should bring value to the product/process, value to the customer as well as value to the producer. The main purpose of innovation is to come out with something or to make someone better which leads to a positive direction. It leads to increased productivity, the increased value of the brand as well as helps in enhancing wealth in the economy. Industrial strategies involve four main types of innovation. (Kuratko & Hodgetts, 2001) which are:

- Invention: Invention involves “breaking” from the existing industry value proposition by creating a new business model.

- Extension: Extension involves adding something new to a current business model to enhance the outcomes in a positive direction.

- Synthesis: Synthesis involves re-combining already existing elements from the current business model to create a new business model.

- Duplication: Duplication involves adding a unique and significant element to a current business model.

The four types of innovation match the two main types of entrepreneurial creativity mentioned by Kirton (1987), That is, ‘Innovators’ and ‘Adaptors’. ‘Innovators’ prefer to break the rules to be creative. ‘Adaptors’ prefer to work within the rules to improve things. When formulating strategy, ‘Innovators’ are more likely to use the ‘Invention’ or ‘Extension’ types of innovation (as well as ‘Synthesis’ if it breaks the rules). Conversely, ‘Adaptors’ are more likely to use ‘Synthesis’ and ‘Duplication’ types of innovation. Combining Kuratko and Hodgetts’ (2001) innovation types with Kirton’s (1987) creativity styles, it is argued can produce Innovator heuristics to facilitate the formulation of entrepreneurial strategy (Dew & Robinson, 2004).

Customer Value

The ultimate goal of entrepreneurial strategy based on creative destruction is enhancing customer value. Such enhancement is not merely limited to product improvement. For example, Southwest’s no-frills airline increased customer value by reorganizing the transportation process. Southwest’s new strategic approach changed the rules of the game in the aviation industry.

The new business model was based on value chain efficiency in the performance of all Southwest’s activities achieved by rapid gate turnaround, which allows frequent departures and greater use of aircraft, Turnaround productivity resulted from flexible union rules, with well-paid gate and ground crews, as well as from no meals, seat assignment, or baggage transfers, which means avoiding performing activities that slow down airlines. Southwest also utilizes airports and routes (type and length) that avoid traffic. This also enables standardized aircraft (Boeing 737) thereby producing unique high-convenience and low-cost positioning (Porter 1996).

Ultimately full-service airlines were adversely affected by this disruption since they could not compete on cost and convenience which Southwest offered, providing improved customer value. Accordingly, creating customer value requires a holistic approach. Few techniques facilitate holism of thinking, especially when trying to envisage a future state that is vastly different from the current. It is not therefore surprising that conflict softens arise when senior members of management teams have differing views of the future. Achieving synergy at the management level is important, otherwise, progress toward actual disruptive strategies may be hampered by interpersonal conflict. For such cases, the Business Ethics Synergy Star (Robinson, Davidsson, van der Mescht and Court, 2006) is invaluable.

However, when considered from the perspective of a single function, it is less than likely that a disruptive strategy will emerge. Quality Assurance Managers may argue that creating customer value simply requires improved quality. Alternatively, Marketing Managers may argue that creating customer value simply requires marketing techniques for improved ‘actual product’ and ‘augmented product’ functions. However, neither of these approaches can produce an effective entrepreneurial strategy since neither explicitly addresses disruption.

Attractive Quality

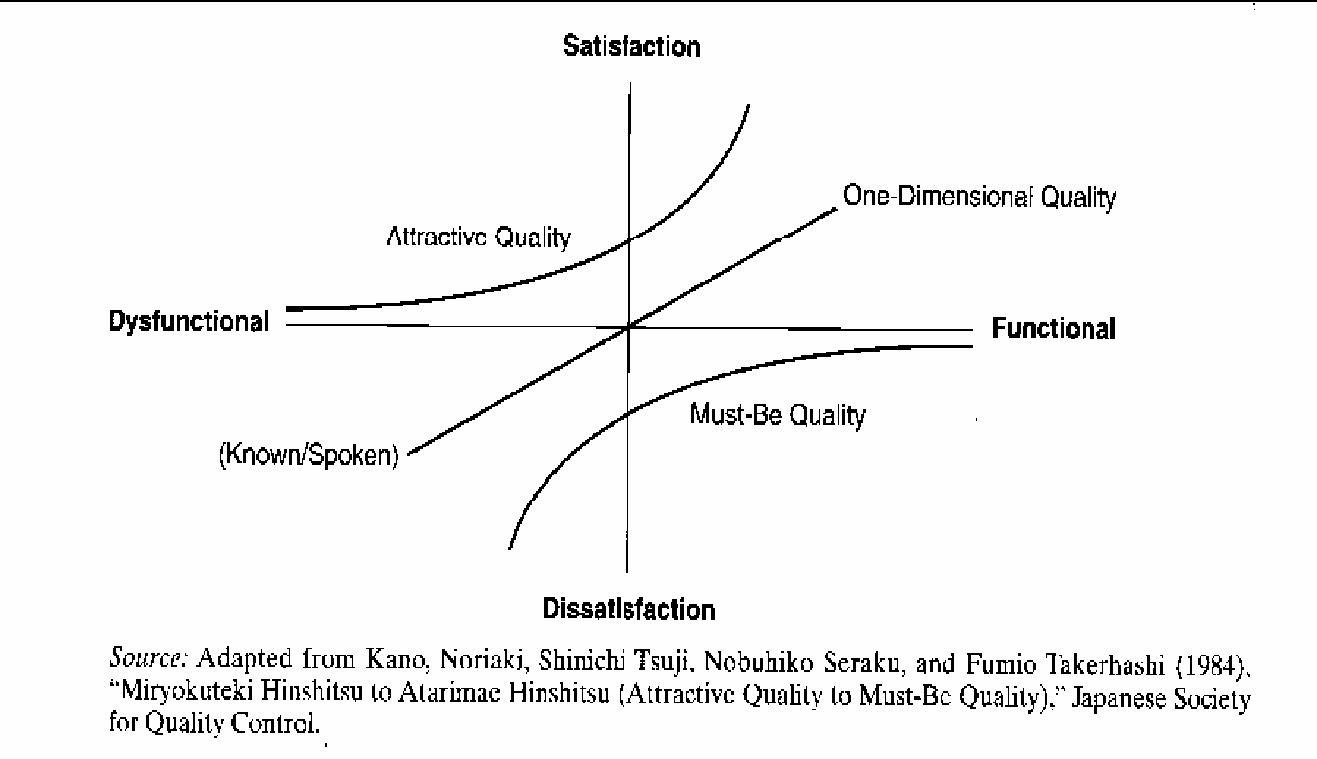

Kano et al’s (1984) diagram (Figure 1, below) identifies three distinct types of quality which correlate to Quality Assurance, Marketing and Disruption perspectives.’ Must-Be Quality (correlating with Quality Assurance) relates to elements that fail to significantly improve customer satisfaction, but without which, customers become dissatisfied. The main purpose of Quality Assurance is to avoid such dissatisfaction. For example, the small joystick mouse located in the middle of a laptop’s keyboard was so small and close to the keys that its use was difficult. Hence laptops with such buttons were regarded as inferior and improving laptop touchpad is not considered a valuable innovation.

‘One-Dimension Quality’ (correlating with Marketing) relates to the relationship between product function and satisfaction, such as actual and augmented product elements, which customers mention when asked for feedback on improvements. For example, the longer battery life of laptop computers provides increased satisfaction, all other things being equal. Hence, longer life battery laptops are regarded as more satisfactory, but since they are usually available to all manufacturers, and not unique, there is little strategic advantage from enhanced functionality.

Distinguished from the above perspectives, ‘Attractive Quality’ (correlating with Disruption) relates to a quantum leap in satisfaction and customer value. For example, a wireless synching feature enabling file transfer from PDA or mobile phone to laptop provides attractive quality for increased satisfaction since it can be proprietary and difficult to imitate for rivals. Thus this differentiation can provide a competitive advantage. However, primary market research cannot assist such a strategy since customers are unable to articulate the value of disruptive innovation before experiencing it, therefore, one must have a means or method to systematically design creative disruptions producing novel attractive quality as well as client value.

Value Innovation

Kim and Maugborgne’s (1997) Value Innovation assists in providing a systematic method for firms to break existing paradigms of industry competition and develop entrepreneurial strategies. Value Innovation aims to increase client value by giving a client more of what it wants, and less of what it doesn’t need. This process relates to elements of both the SCAMPER (Michalko (2000) and Morphological Analysis (Zwicky, 1969; Van Gundy, 1995; Michalko, 1996; and Mattimore, 1994). SCAMPER is an acronym for Substitute, Combine, Adapt or modifies, Magnify or add, Put to other uses, Eliminate or reduce, and Reverse or rearrange. Value Innovation, the new factors are then combined by using Morphological Analysis to form an entrepreneurial strategy.

However, the utility of Value Innovation is limited by neglecting to specifically define industry factors, failing to consider other factors, or new client wants (Dew & Robinson, 2004). Dew & Robinson (2004) postulate a method of combining the drivers of client wants in various ways to develop numerous potential strategies, called the ‘TERMS’ approach. The entrepreneur can then synthesizes (one or more) disruptive strategies, to converge upon a superior business model.

TERMS Technique

The perception of value is a combination of many factors, with every client uniquely weighing factors, making it subjective. (Kotler et al, 1998). The TERMS technique models client value using five generic factors: Time, Emotion, Risk, Money, and Situation. These factors enable entrepreneurs to classify rival and substitute offers in order of relative value, and to assist with changing perspectives to create potential client value.

Using TERMS for Small & Medium Business Disruption Strategy

The TERMS process consists of eight steps (Dew & Robinson, 2004):

- Find out the value curve in TERMS for the industry.

- Visualize a specific buyer from a potential target segment.

- Empathize with the buyer’s TERMS.

- List qualitative TERMS factors that affect the value.

- Find out the most important qualitative factors.

- Synthesize a big business model based on the most significant factors.

- Do again with different explicit customers.

- Select the best business models on the foundation of individuality and segment attractiveness.

Qualities of Entrepreneurs

To become an entrepreneur is not just starting a business or two but is all about having the attitude and passion to succeed in business. It s just not aptitude, but the attitude which decides the altitude of the business. Doing well entrepreneurs has an inner drive to succeed and grow their business, rather than having a high profile business degree or technical knowledge in a particular area. (www.entrepreneur.com, 2008)

Most successful entrepreneurs have the following qualities:

- Taking criticism and rejection positively: There is no such word as no, cant in the dictionary of entrepreneurs. They always take their path if the criticism is constructive and useful for them otherwise they will simply discard their criticism. Before taking any new initiatives or while starting their own business, they know that rejections and obstacles are a part of their business.

- Entrepreneurs always remain highly motivated and energized for their business: For any entrepreneur, self-motivation is key to success. The high goals and objectives of any entrepreneur show that they are highly motivated.

- Competitive Nature: Most successful entrepreneurs live on competition only. The only way to reach their goal and met their self-imposed high values is to compete with successful businesses.

- Huge internal force to succeed: A successful entrepreneur usually has a very healthy opinion of him/her and quite often cultivates a strong and assertive character. They trust their abilities to succeed and aim at high goals. At times this self optimism is mistaken by others as flamboyance or even arrogance but entrepreneurs usually are just too focused to notice or spend too much time thinking about such unconstructive criticism.

- Have an eye to watch out for New Ideas and Innovation: Every entrepreneur has a passion and desire to do things better and to improve their offerings; be it products or services. They are continually looking for ways to improve. They’re creative, innovative, and resourceful.

- Inner Zeal to Get Success: Entrepreneurs are self-driven to succeed and expand the base of their business. They see the bigger image and are often very determined. Entrepreneurs set massive goals for themselves and stay dedicated to achieving them despite the obstacles that get in the way.

- Flexible to Change: If something is not working for them they simply adjust. They know how to keep themselves on top of the business and for this they keep themselves change and updated with time. They update themselves with the latest technology, pieces of equipment and are always ready to change if needed.

True entrepreneurs are passionate, resourceful, and are driven to improve and succeed with time. They are the real pioneers and are comfortable fighting on the frontline. The big ones laugh at them and are criticized but they have their passion which leads to success in their business.

Dark Side of Entrepreneurs

- Salary: there should be a regular paycheck to employees either the business is running in profit or loss.

- Benefits: with the start of the business, there are very few benefits but as the business expanded it go to increase.

- Work schedule: there is no proper work schedule for the entrepreneur. He has to come early and go late as per the requirement of the business.

- Administration: All the decisions of the business are made by the entrepreneur and there is no one above him to take important decisions or monitor the ones that are taken.

- Incompetent staff: Sometimes there is a lack of experienced people as per requirements of the business, so it is very critical to deal with these people.

Strategic Planning

Strategic planning of an organization is defined as the process of defining the strategy of the organization with its goals and objectives and making decisions pr according to capital and resources available. Various techniques can be used in strategic planning, including “SWOT analysis” SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats ) and “PEST analysis” PEST analysis (Political, Economic, Social, and Technological analysis) or “STEER analysis(Socio-cultural, Technological, Economic, Ecological, and Regulatory factors).

Benefits of Strategic Planning

- It makes sure the most effective use of the organizational resources while keeping focus on the key priorities for the organization.

- Providing a platform from which progress can be measured and establish a mechanism for informed change when needed.

- In an organization, strategic planning serves different purposes which include:

- it will help to clearly define the goal and the objectives of the organization, which are real and consistent with the mission and finally achievable in the timeframe.

- Goals and objectives should be clear to each employee of the organization.

- It helps develop a sense of belongingness and ownership.

Other reasons include that strategic planning:

- More focused organizations help to produce more efficiently and effectively.

- Bridge gap between staff and board of directors (in the case of corporations)

- Strong team building in the staff and board of directors

- Provides the glue that keeps the board together

- Produces great satisfaction among planners around a common vision.

- Strong team building in the staff and board of directors

SME’s and Networks

There is now a growing body of literature that attests to the importance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in economic development and poverty alleviation in developing countries. Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have a prominent role to play in the European economy. They are a major source of entrepreneurial skills, innovation, and employment. In the enlarged European Union of 25 countries, some 23 million SMEs provide around 75 million jobs and represent 99% of all enterprises.

Studies on the Role of Networks. (European Commission, 2005). Overall, an SME tends to be independent and managed by its owner or part-owners with a small market share in its industry sector. The definition of SMEs also differs from nation to nation through the general acceptance is that an SME is one that usually is controlled by an individual or a partnership arrangement. The number of employees and turnover also at times defines an SME. In India, the Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) sector play a major and crucial role in the overall economy of the nation. By some industry estimates in terms of value, the sector accounts for about 39% of the manufacturing output and around 33% of the total export of the country. (www.smenetwork.net, 2008)

Numerous studies have demonstrated the important role of entrepreneurial networks in innovation (Humphrey & Schmitz, 1996, Murphy, 2002, Schmitz, 1999,), in promoting mutual learning, and in supporting capacity building (Bangens, 1998, Flora & Flora, 1993). In this study, we define entrepreneurial networks as economic exchanges of a long-term nature as opposed to market or hierarchical-based exchanges. Networks have further been applauded for their role in leveraging resources for the firm (Lechner & Dowling, 2003, Premaratne, 2001). Through networks resource-constrained small firms have been able to enter distant export markets faster than expected (Rutashobya & Jaensson, 2004, Schmitz, 1999), thus challenging many of the traditional internationalization theories.

Entrepreneurs’ Locus of Control

Almost every entrepreneur has a very strong internal locus of control. Locus of control is a concept that defines if a person is having internal motivation or not, is guided by self or not, and is in overall control of his decisions or not. Entrepreneurs believe their future is determined by the choices they make. Psychological profiles are the most used in entrepreneurship research. The trait approach is an attempt to explain key personality factors and their relationship to nascent entrepreneurship.

Human capital

The situational character of start-up decisions is increasingly being emphasized within this body of theory originally conceived as a sub-discipline of neoclassical economics. From this perspective, an individual’s ability to start a company is not decisive, but rather the commercial potential of that individual’s human capital resources concerning various career alternatives (Becker 1964, 1976; Mincer 1974; Schultz 1960). Although this theory is primarily concerned with the human capital resources of non-independent employees; studies have revealed its transferability and applicability to the field of entrepreneurship research.

Intentions Models

Intention models, such as the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), or Shapero’s model of the entrepreneurial event (Shapero, 1984) are of particular interest in tracing the path leading up to new ventures. These approaches look at the time before start-up, in an attempt to explain the individual’s decision to launch an entrepreneurial venture. They are proven to be a good predictor of planned behavior, in particular when that behavior is rare, hard to observe, or involves unpredictable time lags. Intentionality is typical of emerging organizations although the timing of the launch of a new business might relatively unplanned, such as when a sudden new opportunity surfaces (Krueger et al. 2000; Bird 1988). Entrepreneurial behavior is often only weakly predicted by attitudes alone or by exogenous factors that are either situational or individual (demographic characteristics or personality traits) We assume that much of entrepreneurial behavior is planned; becoming a nascent entrepreneur and setting up a new venture is not just as a response to a situational stimulus. In particular, career decisions (as also seen with the human capital theory), are planned in nature and not responses to stimuli. They reflect a process in which beliefs, attitudes, and intentions evolve as we cognitively process our knowledge beliefs and experiences.

Entrepreneurial learning is very easily known as the continuous process that helps in the development of necessary knowledge for being proper in starting up and well managing new ventures. There have been a lot of efforts while investigating the potential learning effects of entrepreneurs’ experiences but hardly focused on the difference between “entrepreneurial experience” and “entrepreneurial knowledge” (Reuber, Dyke, and Fischer 1990) or the “experientially acquired knowledge”. The main difference which comes up is considering the entrepreneurs’ experiences for any new venture creation or events as direct observation, while the practical aspect which an entrepreneur has encountered represents the knowledge acquired from this particular experience (Reuber et al., 1990).

The former can be argued as to experience while the latter is considered equivalent to experimentally acquired knowledge. Studying entrepreneurial learning is mainly equal to comparing the difference between entrepreneurs’ “total stock” of experiences at a given point of time and researchers have then compared this stock of experiences to deviations in the new venture performance. (Bailey, 1986; Box, White, & Barr, 1993; Lamont, 1972; Sapienza & Grimm, 1997).

A major difference that can be directed toward these past approaches is that to know the role of experience in entrepreneurial learning are the findings from literature and research on the new venture performance, which showed that it is very difficult to figure out the effects of single endogenous and exogenous factors that ultimately may influence firm performance (Keeley & Route, 1990; Sandberg & Hofer, 1987; Storey, 1994; Wiklund, 1998). Literature and research suggest that much of the learning that takes place within an entrepreneurial context is experiential (Collins & Moore, 1970; Deakins & Freel, 1998; Minniti & Bygrave, 2001; Reuber & Fischer, 1993; Sarasvathy, 2001; Sullivan, 2000).

This means that complex and past practical experiences from which entrepreneurs learn, are of great importance as they will help in to understand entrepreneurial learning better. Past research suggests that role of experience and in particular prior start-up experience, as a substitute for entrepreneurial learning (Box, White, & Barr, 1993; Lamont, 1972; Ronstadt, 1988; Sapienza & Grimm, 1997). Despite this, the current knowledge of how entrepreneurs are learning from past experiences is rather scattered. (Reuber & Fischer, 1999; Stare Bygrave, & Tercanli, 1993).

Now having understood the basic difference between the experience of an entrepreneur and the knowledge acquired, we can work on investigating the experimental process where the practical and personal experience of the entrepreneur is continuously transformed into knowledge. A conceptual framework was developed, to organize the different arguments and reflections on the process of entrepreneurial learning that has been found in the literature. The term conceptual framework is laid as the basic goal for the initial stage for the better advancement and understanding of entrepreneurial learning as an experiential process by exploring antecedents and results of the changing process of entrepreneurs’ experiences, rather than to fully specify the model.

Knowledge and the firm

Entrepreneurial knowledge is not only dependent on individual personality and cognitive capacity but is also ‘situated’. For most studies, the overriding ‘situation’ is the institution of the firm and its immediate network. For example, Takur (1999) found that whilst management capability had a strong determining influence on venture growth, this influence was only manifest in the ability to organize; in this case, using resources to create space, or ‘slack’ needed by others to exploit opportunities.

The influence of these virtual cycles in terms of their contribution to the development of entrepreneurial spirit has been brought out in a few studies. (Minguzzi and Passaro, 2001). This study was also able to distinguish between ‘learning entrepreneurs’ and ‘bounded entrepreneurs’. Proximity to final customers provided ‘learning entrepreneurs’ with a stimulus for change, while ‘bounded entrepreneurs’ tended to avoid and resist change in favor of focusing on the production of existing commodities (Minguzzi and Passaro, 2001).

Rather than accept the identification of entrepreneurial spirit with a willingness to adapt and undergo renewal the authors also identified, how the availability of regular, orthodox, and mutually re-enforcing knowledge in demographically knit market conditions encouraged entrepreneurs to resist innovation and discontinuity. Where the final market is changeable entrepreneurs were increasingly flexible but in other markets, entrepreneurs preferred existing distributions of knowledge and the comfort of using familiar solutions. The closer to the final consumer and the more direct the relations (the fewer the intermediaries) the more open and successful is the entrepreneurial activity (Minguzzi and Passaro, 2001). They investigate the importance of social capital to the acquisition and use of knowledge from the perspective of the key customer relationships of young high-tech SMEs.

Promotion is an area of entrepreneurship policy worthy of further development because of the critical role it plays in fostering a culture supportive of entrepreneurship changing mindsets and influencing the motivation component of the policy framework. The first stage of the individual entrepreneurial process begins with the awareness that the option exists. This is followed by the formation of attitudes and beliefs, personal identification with the entrepreneurial role, formation of the intent to start a business, the search for an idea, the business planning, and preparation phases, and, finally, the start-up. These researches determined that a person’s motivation to explore entrepreneurship is initially heavily influenced by external factors like entrepreneurship culture or the existence of entrepreneurial “heroes”, which bear an influence on each person’s occupational entrepreneurial identity.

Regions are complex ecosystems, and entrepreneurship is a complex phenomenon. To facilitate entrepreneurship on a broader regional scale with sustainable effects a systems approach is required. This is considered also in European initiatives like the ‘Lisbon Strategy’, the ‘Green Paper on Entrepreneurship in Europe’ and the corresponding ‘Opinion of the Committee of the Regions’. Still, too many regional policy approaches neglect the complexity employing using superficial, short-term, or isolated concepts. The entrepreneurship rationale demands a holistic approach.

An education system is a mirror of the dominant values of a certain region and society. If entrepreneurship shall be important for a region, education is, therefore, a vital starting point. The regional promotion of entrepreneurial spirit and competence within education is a grass-roots approach to promote the entrepreneurial learning of individuals, social settings, and organizations.

Entrepreneurship is interaction and does not exist in a vacuum. As an entrepreneur, one would integrate others’ expectations and outside developments into one’s ideas and activities. Thus, reflection and interaction are core dimensions of entrepreneurial competence. Learning which aims at improving reflection and interaction contributes to personal growth. If we base entrepreneurship training and education on the learning goal of personal growth we enable entrepreneurship pedagogy and can support entrepreneurial activity.

Opportunities to professionalize will have a positive impact on entrepreneurship training and promotion. Training of Trainers (ToT) can offer such opportunities for teachers, lecturers, consultants, incubator managers, and even advanced students. It should be also open for entrepreneurship promoters in politics and administration. The BEPART approach is the development of an international ToT program based on a broad concept of entrepreneurship and an ‘action learning approach’. It aims to learn from and with each other, as well as to support international exchange and dialogue in the field of entrepreneurship education and promotion.

The importance of small and medium-sized enterprises for today’s economy through, for example, job creation and economic growth have often been highlighted. The service sector employs the majority of employees in Western countries and, as such, entrepreneurship within this sector receives growing attention (Dobon and Soriano, 2008). Many research endeavors have aimed at identifying factors that explain how business owners make their fundamental contribution to economic development (Altinay & Altinay, 2006; Bryson, Keeble & Wood, 1993).

Despite the important insights gained from these studies little, however, is known about possible different types of business owners within the service industry. The need to differentiate between different types of business owners when studying business success is an important issue, because different groups may strive for different goals and thereby depend on different success factors. Recent investigations showed, for example, that business owners who are guided by personal values of power and achievement, find business growth a more important success criterion, and hence also have larger businesses, than business owners who value power and achievement less (Gorgievski & Zarafshani, 2008). In contrast, business owners with other value orientations, such as benevolence, valued other success criteria more, such as having satisfied customers and employees, or social and environmentally friendly enterprising. Not distinguishing between such groups may foreclose an effective capturing of the factors that enhance the performance of each of these groups.

Traditional discriminators between business owners and non-business owners

In the literature, two major individual difference approaches to describing business owners can be distinguished: a personality and a competency approach. The personality approach focuses on relatively permanent traits, dispositions, or characteristics within the individual that give some measure of consistency to that person’s behavior. (Feist & Feist, 2006). More recently, the focus in entrepreneurship literature has shifted towards a broader assemblage of branded entrepreneurial competencies, which also include knowledge, skills, and abilities that assist people in their efforts to exploit opportunities and establish successful ventures, and that is generally believed to be more attainable, variable and subject to cursory change than personality characteristics (Baron & Markman, 2003; Baum, Frese & Baron, 2007).

Many entrepreneurial decisions will involve ambiguity because decisions result in actions that are innovative and original. Scheré (1982) referred to the role of the entrepreneur as “an ambiguity-bearing role”. He found that entrepreneurs display more ambiguity tolerance than managers. It was also found that firm founders scored significantly higher on tolerance of ambiguity than did managers. (Begley and Boyd, 1987a) In a more recent study, Koh (1996) confirmed that tolerance of ambiguity is one of the essential features differentiating entrepreneurs from people who are not entrepreneurially inclined.

However, several studies did not replicate these findings (Shane et al., 2003, Babb and Babb 1992 and Begley 1995) found no significant difference intolerance of ambiguity between founders and business owners who had acquired an already existing firm, or founders and managers. Regarding the difference between entrepreneurs and small business owners concerning growth and innovation, we expect that entrepreneurs will face more ambiguous and uncertain situations than small business owners (Timmons, 1990). Small business owners can be expected to face more stable and well-known situations, and people who are less tolerant of ambiguity may more likely seek such environments.

Corporate entrepreneurship can leverage a firm’s financial resources, market knowledge, and managerial expertise to introduce a new or improved product, feature, or process to market. Compared to innovations started by “two guys in a garage,” entrepreneurship within a firm has the advantage of access to the firm’s market and industry experience. The challenge of corporate entrepreneurship is that the risk-averse culture of traditional corporations stifles opportunities for innovation.

To promote entrepreneurship within a corporate environment, firms must release their grip on efficiency and instead embrace the failures which enable them to learn new ideas and methods. They must empower the innovative leaders with access to senior management, and equip them with the support of cross-functional teams. These mechanisms and structures form a sustainable competitive advantage that enables a firm to create and capture more value, more quickly.

Intra-Corporate Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurial activity within a corporation is the ability to create and capture added value beyond that which the corporation is currently doing. Value creation can result from new products or services, improvements in current product or service offerings, or process improvements. Central to the idea of value creation is the concept of innovation. Innovation is closely tied to entrepreneurshipin entrepreneurs and is an essential component of fostering entrepreneurial activities within a firm. To foster entrepreneurial activities within an organization is to enable a culture of learning and innovation.

Learning and innovation involve tradeoffs that have to be made against efficiency and performance. Innovation naturally leads to taking risks and exploring new ideas. This runs counter to operational efficiency and also means taking risks that inevitably lead to failures as well as successes. Thus, cultivating entrepreneurial activities within a firm means introducing operational inefficiencies and failures. For firms that follow a low-cost strategy, entrepreneurial activities can lead to a short-run competitive disadvantage against competitors that strictly follow a low-cost strategy. The cost of failure can cut into the thin margins of the established firm. However, the short-run disadvantage can evolve into long-run advantages if the company seeking innovation is successful in creating and sustaining additional value.

Thus the main thoughts that rake up the mind of entrepreneur are the arrangement and alignment of resources. He has to take care that the business is not stranded up due to resources. He has to maintain a balance and ensure that the growth’s momentum does not slow down nor is the business stretching too much.

Identifying and Cultivating Entrepreneurs

The entrepreneurs are a firm’s hands-on champions who develop ideas into added value. The entrepreneurs need not be the source of an idea, though often they are. An entrepreneur’s primary purpose is to identify the potential value in an idea and passionately champion the idea within the firm to capture the value. The entrepreneur is a visionary who is internally motivated by challenge and a strong sense of what is needed by the firm, not by promotions. The entrepreneur undertakes great personal risks in the form of forgone time or salary while working to overcome obstacles in the organization.

Personal risk is necessary for success, as it serves to increase the entrepreneur’s conviction and drive. Obstacles in the organization also challenge the entrepreneur and augment his conviction and internal drive. The risk and obstacles instill a sense of rationality in the entrepreneur. Without personal risk and obstacles, the entrepreneur might pursue ideas with little chance of adding value to the firm. A system of risk and obstacles serves to reinforce the concepts of conviction, drive, and focused innovation.

In the modern-day economy when businesses are falling like a pack of cards; the importance and scope for SMEs are on the rise and this provides just grounds for budding entrepreneurs to go on the hunt. The market is facing tough competition and optimistic people trust that this will help the process of market development.

There was a progressive liberalization of European air routes by the European Commission throughout the 1990s, notably facilitating the entry of new firms. During this period, several low-cost carriers emerged, notably Ryanair and EasyJet. Significantly, these new entrants operated a very different business model from that of the traditional scheduled carriers. It was anticipated that fierce price competition would ensue.

The introduction of competition can sometimes lead to substantial reductions in price. For both international telephone calls and European economy airfares, the average price was comfortably more than halved within a decade. In two other cases (new cars and replica kits), very significant reductions (10 %+) were observed. On the other hand, in neither book retailing nor (particularly) retail opticians is the evidence entirely conclusive.

Competition can be enhanced in several ways. This certainly includes competition policy per se (e.g. replica kits, NBA, new cars), and deregulation/ liberalization (e.g. airlines, international telephone calls, opticians), but also the market itself can throw up new opportunities (e.g. rapid technological advance in telecoms).

Although government policy may often be important and necessary for change, it is rarely sufficient. We also need a pool of resourceful entrepreneurs, capable of exploiting changed market conditions (e.g. Ryanair, Specsavers, and OneTel). 4. Competition is not just about the price, it is typically multi-faceted. Sometimes freeing up a market stimulates new ways of doing things (e.g. new business practices by low-cost airlines, changing retail book outlets, spectacles as a fashion item). These are generally unpredictable ex-ante, but may ultimately be worth more than just a lower price.

Until the early 1990s, the aviation market in Europe (and most other parts of the world) was heavily regulated in terms of access of airlines to routes, and prices were fixed, to a greater or lesser extent, by international agreement. This chapter examines the impact of the liberalization which took place through the 1990s. It was anticipated that this would produce new entry, and this is exactly what happened with the emergence and rapid growth of low-cost airlines. However, these firms, notably Ryanair and EasyJet in the UK, were not just entrants, they were entrants with a quite different business model from that of the traditional airlines, and so this is a story of liberalization coupled with innovation.

Change in the competitive environment

Although this is a study of the impact of liberalizing a market by opening it up to the entry, it is as much about the impact of the new business practices introduced by the entrants. While the former was a necessary condition for the latter, it was no sufficient. Thus it is a story of the effects of a combination of

- removal of market imperfection and

- entrepreneurial initiative.

We shall not attempt to disentangle their relative contributions, since the two are inextricably linked. We now introduce both in turn.

European Aviation Industry’s liberalization

Before liberalization and the establishment of a single European market in 1993, the air transport market in the EU was a collection of separate national markets. Within each member state, domestic air transport was governed by national rules, which varied in their competitive nature. Although the UK domestic market was more liberal than most other European domestic markets, the regulatory system helped to protect the interests of national carriers rather than promote competition. International air transport between member states was governed by bilateral air service agreements between each pair of member states. This restricted access to markets and often allowed only one airline to operate a service on a limited number of specified routes. The airlines met and coordinated fares through the International Airline Tariff Association (IATA), which was formed by a group of scheduled airlines in 1945. At IATA conferences airlines broke off into separate meetings to discuss fares by country pair.

Low-Cost Airline: Sector Development

The emergence of low-cost airlines has been undoubtedly the most striking development post-liberalization. These airlines have adopted the business model pioneered by the US domestic airline Southwest. For UK consumers, whose travel originates in the UK, there are currently two main low-cost carriers: Ryanair and EasyJet. Since liberalization, a number of other low-cost carriers have entered and exited the market, including BA’s Go and KLM’s Buzz (acquired respectively by EasyJet and Ryanair). Low-cost carriers offer a differentiated product when compared with traditional schedule and charter carriers. The key to their success has been their low-cost strategy, which has allowed them to charge very low fares. Their product is clearly defined as a point-to-point service provided at the lowest possible cost. Immediately post-liberalization was estimated that low-cost carriers could achieve unit costs as low as half those of major traditional carriers (CAA (1998, p.ix)). More recently traditional carriers have been able to reduce their costs, but low-cost carriers still have a cost advantage. Low-cost carriers successfully minimize their costs by:

- The use of a homogenous fleet; this reduces pilot training costs and means it is easier to obtain spares and maintenance services on favorable terms. It also simplifies the scheduling of crews and equipment;

- Outsourcing various functions, especially maintenance and handling, which they obtain at competitive prices without the need to maintain a specialized labor force;

- The pressure that they exert on suppliers to obtain contracts on the most favorable terms;

- The introduction of smaller/narrower seats;

- Not providing free drinks or meals on flights; not only does cut catering costs but also allows the airlines to operate with fewer staff;

- Selecting airports that need the use of the airline and therefore offer them concessions on airport charges;

- Minimizing turnover times and therefore increasing aircraft utilization. This is achieved by free seating;

- Staff working longer hours; and

- Lower distribution costs; most tickets are now brought online and customers simply receive an email confirmation, so there is no need to use travel agents.

The major marketing strategy that these airlines employ is to keep costs minimum on account of frills and use timely departures and arrivals as their USP. Business travelers prefer this class of service on account of being cost-effective and timely. Usually, small haul trips are preferred by such airliners. The host nations in such cases may decide to generate some more revenues in form of taxes since the airlines work on considerable margins. The recent years have seen a downturn for the aviation industry owing to reduced air travel post 9/11 and rising aviation fuel. Thus the government should hold up any moves to tax these airlines anytime soon.

References

- CAA (1998), The Single European Aviation Market: the first five years (CAP 685), Civil Aviation Authority, London.

- CAA (2002), The Aviation Safety Review: 1992- 2001 (CAP 735), Civil Aviation Authority, London.

- CAA (2003), The Future Development of Air Transport in the United Kingdom – The CAA’s response to the Government’s consultation documents on air transport policy, Civil Aviation Authority, London.

- Kohli, A. K., and B. J. Jaworski (1990). Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Proposition, and Managerial Implications, Journal of Marketing 54(2), 1-18.

- Narver, J. C., and S. F. Slater (1999). The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability,” in Developing a Market Orientation, Ed. R. Deshpande. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, (P 45-77).

- Pinchot, E., and Pinchot, G. (1978). Intra-Corporate Entrepreneurship.

- Pinchot, E., and Pinchot, G. (1996). Five drivers of innovation.

- Ahmed, S.U. (1985). nAch, risk-taking propensity, locus of control and entrepreneurship. Personality and Individual Differences, 6, 781-782.

- Begley, T.M., & Boyd, D.P. (1987b). Psychological characteristics associated with performance in entrepreneurial firms and smaller businesses. Journal of Business Venturing, 2, 79-91.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management (17), (P 99 -120).

- Barney, J., & Arikan, A. M. (2001). The resource based view: Origins and implications. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishers.

- Dew, R. & Robinson, D. A. 2004. TERMS – Creating Disruptive Entreneurial Strategy. Regional Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Regional Entrepreneurship Research Exchange. Australian Graduate School of Entrepreneurship, Melbourne.

- Dollinger M.J. (1999). Entrepreneurship Strategies and Resources. Prentice Hall, US.

- Leonard D. & Rayport J.F. (1997). Spark Innovation Though Empathic Design Harvard Business Review.

- Michalko M (2000). Four steps toward creative thinking, The Futurist Washington Vol 34 Iss 3 (P 18-21).

- Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Barras, R. (1984). Towards a theory of innovation in services, Research Policy 15: (P 161-73).

- Cabral, Regis (2003). Development Science, The Oxford Companion to The History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 205-207.

- European Commission, (2005), “The new SME definition”.

- Entrepreneur Website, (2008).

- Entrepreneur Website, (2008). Web.

- SMENetwork Website, (2008).