The firm and the operational processes required to create, manufacture, distribute, and use an item or brand are referred to as supply chains (Hugos, 2018). By proactively managing connections with supply chain partners, a business organization can achieve a competitive edge (Lambert and Enz, 2017). Additionally, Hugos (2018) insinuates that organizations that understand how to create and engage in solid supply chains will significantly competitive edge their marketplaces. Companies rely on their supply chains to offer them the materials and services they require to thrive and grow (Hugos, 2018). Every company is a part of one or more supply chains and plays a role in each of them. Hugos (2018) enumerates that because of the unpredictability of how marketplaces will unfold, it is becoming indispensable for businesses to be proactive in addressing the supply chains in which they engage.

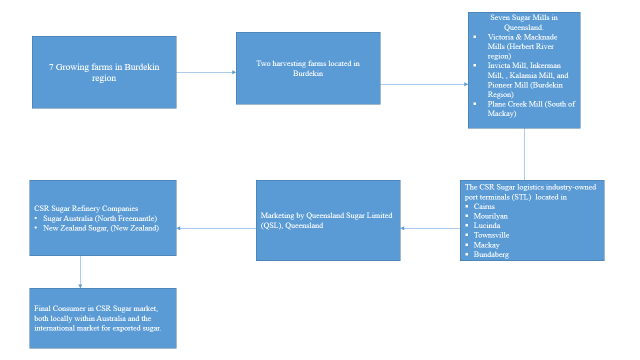

The primary supply chain entities for their geographical locations for CSR Sugar Australia include the following. The chain begins with the seven growing farms in the Burdekin region, Australia. Connellan (2016), in his research, ascertains that sugarcane is produced in the area. Still, in Burdekin, two harvesting sugar companies deal with harvesting the sugarcane from the growing farms. It then owns and runs seven sugar mills in Queensland (Valix et al., 2017). In the Herbert River region near Ingham are Victoria Mill and Macknade Mill. In the Burdekin Region are the Inkerman Mill, Invicta Mill, Pioneer Mill, and Kalamia Mill (Valix et al., 2017).

To the south of Mackay is the Plane Creek Mill. Under milling, Cogen, a subsidiary of CSR Sugar, helps with sugar production across the seven mills (Valix et al., 2017). The CSR Sugar logistics industry-owned port terminals (STL) are located in Cairns, Mourilyan, Lucinda, Townsville, Mackay, and Bundaberg. The marketing of the product is then done the Queensland Sugar Limited (QSL), based in Queensland. The last supply chain entities of CSR Sugar Australia are the refinery companies. They are Sugar Australia, located in North Fremantle and New Zealand Sugar.

Key Roles and the Logistical Functions of the CSR Sugar Supply Identities

The various supply identities involved in the supply chain of CSR Sugar play vital roles and logistic functions in ensuring a smooth transition of the sugar product at each stage. The seven growing farms in Burdekin use weather and climatic data frequently in groundwater technologies for sugarcane cultivation. Significant attempts have been made to use climatic data to calculate the ideal irrigation period for a potential operation to produce the highest output (An-Vo et al., 2019). The two harvesting companies in Burdekin play an essential role in the transportation of the harvested sugar from the farms and consequently storing them in their respective warehouses before being transported for milling.

The seven sugar mills in Queensland are vital since they process the product, packaging the product, warehousing, and transporting it to the QSL marketing board for sales purposes. The CSR Sugar logistics industry ensures proper inventory control of the sugar product as it handles across the different chain entities. Additionally, they assist in material handling of the product to ensure that fewer damages are incurred in handling the product. The QSL logistical functions include the advertisement and promotion of the CSR Sugar products to the various CSR Sugar markets internally and externally. The refineries’ logistical functions and roles include warehousing, packaging, inventory control, and transportation to the desired markets and the QSL.

How each of the Entities Manages their Relationship with their Supply Chain Partners

Efficient and effective supply chain partnerships, as well as long-term interactions can improve long-term productivity. Such diverse partnerships should be carried out more inventively among supply chain participants (Govindan et al., 2016). Companies must implement some efficient regulating systems to handle such interactions and alliances. As the purpose of entrepreneurship in peace grows in importance, various issues have arisen on how to efficiently coordinate initiatives and harmonize the social and commercial goals of the institutions engaged (Kolk and Lenfant, 2016). The seven growing farms and the milling companies enter into partnerships to share the costs and benefits of the crop. By sharing the costs and benefits, in cases where they are faced with competition for restricted resources, organizations that collaborate can receive more reserves, reputation, and incentives (Liao et al., 2017).

The CSR Sugar logistics-owned company and the QSL ensure information sharing to gain a competitive edge. Because there is an enormous amount of generated information between the two entities, it is critical to select the most usable information on important transactions that can contribute to supply chain enhancements (Nakasumi, 2017). Due to the higher demand for CSR Sugar, the QSL and the refineries maintain effective collaboration and management by sharing information regarding the latest technological methods in marketing and manufacturing. The present use of software, for instance, ERP, encourages these supply chain counterparts to rely on computerized systems to offset the effects of market unpredictability (Khan et al., 2016).

Because the supply chain developed long and many supply chain entities are involved, the supply chain is generally complex for this product. The extended supply chain enumerates that more costs are incurred in farming, harvesting, transportation, production, and distribution to the final consumers or markets. With the costs being incurred at the different stages towards realizing a quality end product, the cost of sale to the final consumer will be high. For instance, the QSL mandated with the marketing will incur product promotion costs that will lead to CSR Sugar’s high price cost.

References

An-Vo, D.A., Mushtaq, S., Reardon-Smith, K., Kouadio, L., Attard, S., Cobon, D. and Stone, R. (2019) ‘Value of seasonal forecasting for sugarcane farm irrigation planning.’ European Journal of Agronomy, 104, pp.37-48.

Connellan, J.F. (2016) Nitrogen accumulation in biomass and its partitioning in sugar cane grown in the Burdekin: ASSCT peer-reviewed paper.

Govindan, K., Seuring, S., Zhu, Q. and Azevedo, S.G. (2016) ‘Accelerating the transition towards sustainability dynamics into supply chain relationship management and governance structures.’ Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, pp.1813-1823.

Hugos, M.H. (2018) Essentials of supply chain management. John Wiley & Sons.

Khan, M., Hussain, M. and Saber, H.M. (2016) ‘Information sharing in a sustainable supply chain.’ International Journal of Production Economics, 181, pp.208-214.

Kolk, A. and Lenfant, F. (2016) ‘Hybrid business models for peace and reconciliation.’ Business Horizons, 59(5), pp.503-524.

Lambert, D.M. and Enz, M.G. (2017) ‘Issues in supply chain management: Progress and potential.’ Industrial Marketing Management, 62, pp.1-16.

Liao, S.H., Hu, D.C. and Ding, L.W. (2017) ‘Assessing the influence of supply chain collaboration value innovation, supply chain capability and competitive advantage in Taiwan’s networking communication industry.’ International Journal of Production Economics, 191, pp.143-153.

Nakasumi, M. (2017) ‘Information sharing for supply chain management based on block chain technology’. In 2017 IEEE 19th Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), 1, pp. 140-149.

Valix, M., Katyal, S. and Cheung, W.H. (2017) ‘Combustion of thermochemically torrefied sugar cane bagasse.’ Bioresource Technology, 223, pp.202-209.