A Company Situationer

Transcom Worldwide is a global outsourced business process provider. Nearly a decade old and riding the technology wave of Internet-enabled information processing and remote communications, Transcom was a Swedish start-up that is nominally headquartered in Luxembourg but really maintains its operational nerve centres in St. Albans and Leeds. From these two sites, the listed company controls ‘near-shore’ subsidiaries in Lithuania and Estonia, a major offshore group in the Philippines, subsidiaries and affiliates in virtually every European nation, in Canada and the United States. In the past two years, moreover, Transcom has established beachheads in North Africa, South America and the Middle East. All in all, the company operates 75 service sites in 29 countries and employs in excess of 21,500 full-time employees.

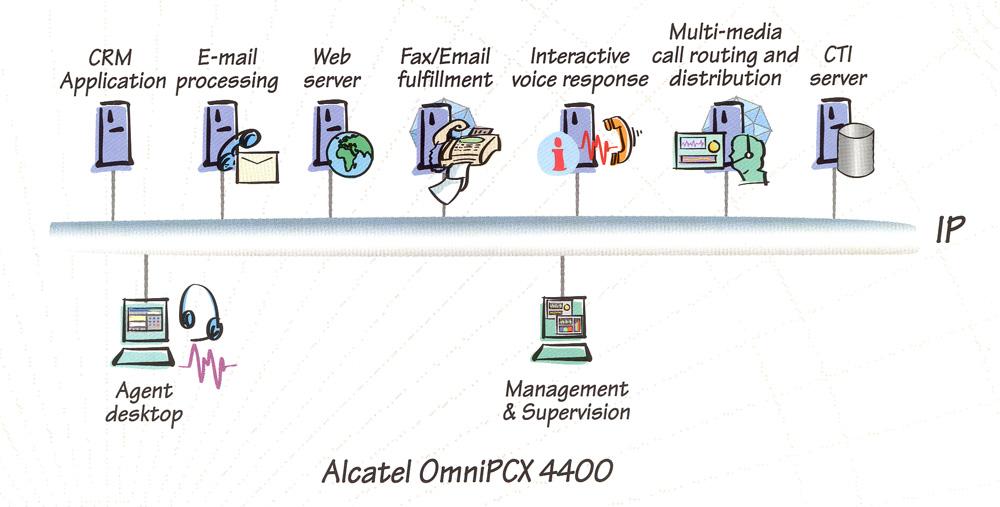

Having come this far in almost no time at all is not even atypical since a global survey reveals that individual sites are just eight years old (Holman, Batt, and Holtgrewe, 2007). This is consistent with the fact that cost-efficient call centre operations needed the development of voice-over-IP telephony to cut down on long-distance call costs, as well as “Web 2.0” technologies such as interactive voice response (IVR), chat, forums and real-time monitoring of remote desktops.

Company Objective, Vision and Scope

Daring to set its sights beyond the prosaic confines of call centre operations, Transcom has lived the vision of innovation by diversifying into the variety of business process outsourcing (BPO) services shown in Table overleaf. Since every site has a ‘remarkably national face’ and tends to serve local clients (Holman, Batt, and Holtgrewe, 2007), Transcom is on track to grow revenue organically by both geographic expansion and, following the billion-dollar example of New York-based Convergys, gain a fair share of the lucrative North American market.

To ensure uniform application of management tenets earned from comparatively long experience, the company strives for the consistent application of an organizational climate characterized by the “…values of Honesty, Passion, Fun, Innovation and Excellence. Our ultimate goal is always to excel by being honest, passionate and innovative while enjoying what we do…” (Transcom, 2009c, p. 3 ). Such an emphasis on the human relations aspect of management may seem like lip service to platitudes but it is in fact the only possible answer to the resource structure of BPOs everywhere.

In essence, the business of Transcom is to provide clients an external resource for carrying on necessary but ‘non-core’ activities. A business looking to reduce overhead in general and management span of control, in particular, will not mind outsourcing many administrative departments: maintenance, security, temporary staff, customer service, large document processing jobs, promotion and refund fulfillment, legal research, collection of moribund accounts, telemarketing, etc. And this is where international chains like Mondial, Convergys, and Accenture compete with Transcom.

All BPOs must compete to acquire and retain clients on cost because cost saving is the primary rationale for a business to outsource one or several business processes to independent third parties. Other than location and head office overhead, the components of direct cost at each site are limited to manpower, computing and communication (C & C) equipment and their associated software. The cost of both C & C hardware and software is not a factor since it is the same for both the client and the outsourcer. The software itself does not contribute materially to saving by outsourcing. In the first place, some clients who buy or develop specialized customer-service (CS) software are perfectly willing to have their outsourcer install this on the latter’s premises. Secondly, the last five years have seen a steady shift in software development, away from pricey industry leaders offering off-the-shelf products to enthusiasts who develop substitutes that they then release to the “open source” community free of charge.

Therefore, the real cost difference between client and outsourcer is that the latter is free to operate without bloated company overhead and with young recruits not entitled to extra benefits because of seniority. An equally critical factor is that call centers offer no job security since very stringent performance metrics are the rule. Nonetheless, Transcom is unique for cross-training an account team for other work instead of letting all go when an account is lost to a competitor.

To understand the cost advantage is to have insight into why a diverse range of clients in financial services (AIG, Grupo Santander, Citibank), telecoms (Orange), media and technology (Sky.it, Xerox), retail (Future Shop/Best Buy, Yves Rocher), and travel and leisure (Expedia, Scandia), to name just a few, chose to give some or all of their European outsourcing requirements to Transcom.

At the end of the fiscal year 2008, Transcom reported €631 million in revenues from three principal lines of business. These spanned customer relations management (more familiarly referred to as ‘call centres’), credit management (collecting on past-due accounts), and miscellaneous ‘customer-related solutions’ that included interpreters, paralegal services, and systems/productivity consulting for other call center chains (Transcom, 2009b). The complete declared scope of Transcom business:

Source: Transcom (2009c)

The Business Process: Measuring Intangible Performance

For all of FY 2008, Transcom managed 2.5 million collection cases and about 21 calls per productive seat/shift for a total of 145 million calls handled all year round. Every single conversation with a customer is a complex process, generating performance assessment and monitoring measures (‘metrics’ for short) that all link to measuring cost efficiency whilst meeting service level agreements (SLA’s) with the client.

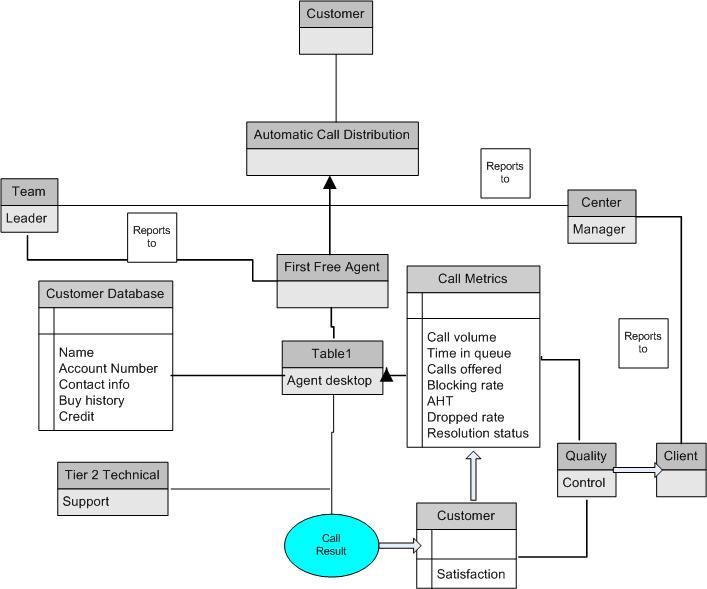

Call center managers need to assess a lot of tactical performance metrics. Starting with time and output reports for a given city-location, massive real-time computerization has given the ability to “drill down” to account teams handling one client, the three-shift units that make up each account, and so on down to the individual agent whose metrics are three standard deviations lower than either the standard or the team average.

Figure 1 (overleaf) is one overview that reveals the rationale for call queue metrics. The first challenge is to accommodate all callers who need to address some concern with customer support agents who, they believe, work in-house in the cable company or bank that issued their credit card statements. Thousands of calls can come in at any given minute or hour, during the holiday shopping season, or on the week when subscribers receive their statement of account. Hence, the most fundamental metric is: what proportion of callers get to talk to a live agent?

From the viewpoint of callers, the critical criterion might seem to be: a) whether they get a ringing tone right away; and, b) how much time they spend in the queue, listening to a recording (‘we value your business, please hold…’), before finally getting an agent to whom they can relate their problem. The first criterion is a matter of investing in enough trunk lines. All subsequent performance metrics reflect staffing decisions and quality of training.

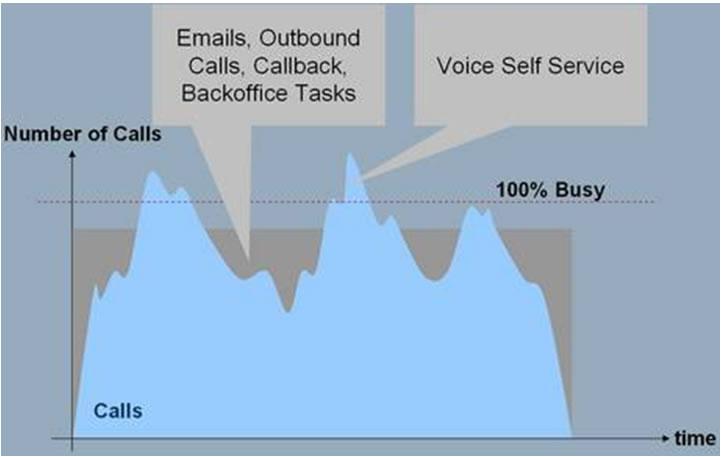

So, to start with, total call volume is assessed critically, by the agent, by the shift team and the account team. This varies seasonally (e.g. airline and hotel CS teams get more calls during the peak travel season, naturally), working day or holiday, even by hours during the day and night. In the course of an eight-hour shift, Figure 2 (below) illustrates how incoming call volume can ebb and flow. From Operations Research, Erlang C calculators can help with staffing decisions to ensure there are enough agents to meet all known peaks in call demand (Eastbay, 2009). In case there is an unexpected overflow of calls, some contact centers insert interactive voice response (IVR) right after the entry point trunk hunting program: if no free agents can be found after a reasonable waiting time when the caller hears ringing tones, IVR kicks in and guides the caller through a preliminary series of questions where computerized scripting prompts the caller to enter his account number, contact number and indicate his concern from a multiple-choice list. If at the end of this process, an agent is available, then the information already entered by the caller immediately displays onscreen and this cuts short the preliminaries. If the call queue remains absolutely congested, the script can take care of promising the customer a callback.

Slack periods are more easily dealt with by having agents do outbound sales, respond to pending emails, callback requests and catching up with updating the file of customers who have called that day.

DW Requirements and the Existing System

In order to manage for efficiency and provide clients hard data about fulfilling the service levels agreed to at the start of the engagement, Transcom must provide clients such measures as:

- Service level = The percentage of all incoming calls answered by a live agent within so many seconds or minutes (e.g. 90 seconds), net of dropped calls before the time cut-off is reached. This is a “strategic” statistic since SL dictates how many telephone trunk lines should be installed and how many agents should report at what times of the day, after accounting for “normal” absenteeism (but not tardiness because this is ruthlessly minimized) and to take up the workload when others take meal and coffee breaks. This is the first and most essential element of maintaining customer satisfaction, aimed as it is at the risk that a complaining customer who cannot get through might decide to switch to another brand or service.

- Blocking rate = The percent of calls “offered” (meaning total agents available to take calls that very minute) that are not allowed into the system; generally % of callers receiving busy signals even after repeated tries. Since this is the converse of Service Level, the customer-oriented client who pays for enough agents and facilities to attain 99% SL in effect demands no more than 1% Blocking Rate from his outsourcing center.

- In turn, average handling time (AHT) is a measure of productivity. AHT is the sum of average “productive” talk time (ATT) + average after call work time (ACW), both divided by the number of calls handled for the hour or day. ACW amounts to all the necessary “paperwork” and recordkeeping after each call (Bergevin, 2005). The longer AHT is, of course, the less productive an agent is.

- First-call resolution: This refers to the proportion of completed calls that require neither a callback nor the customer calling again to follow up on a product or service problem. This metric reflects several system issues such as agents so well trained they readily provide answers on the first call, ease of accessing knowledge databases on the agent’s terminal so as to identify solutions for comparatively rare queries, built-in utilities for ‘escalating’ knotty problems to more experienced ‘tier 2’ agents or specialized technical support, and the speed with which clients themselves can say, honor warranty claims. ‘First call resolution’ is obviously a customer satisfaction matter.

- Customer Satisfaction Rate (CSAT): At the end of a transaction or conversation, Transcom might give clients the benefit of customer satisfaction feedback from the caller. To prevent bias, the agent disconnects and an IVR program comes online with the customer. This CSAT subroutine can be as straightforward as a script that says, ‘Press 9 on your handset to indicate that you were totally satisfied, 0 if you were completely disappointed, and any other number in between that will accurately convey your satisfaction with the way your concerns were addressed.’ This should normally reflect satisfaction with agents’ handling of the complaint, service request, or record update. But all those who feel they waited too long in the call queue to be attended to will certainly modulate their opinions no matter that the customer service call went smoothly when they finally got through.

The Rationale for a Data Warehousing Solution

All of the aforementioned performance metrics can be collected manually, inputted into spreadsheets and chartered for the sake of call center management and clients as well. However, this is slow, tedious, mistake-prone and totally inefficient in the fast-paced environment of outsourced CRM and credit management. This becomes more obvious when one considers that the channels available to customers have multiplied as net-based technology progressed (Figure 3 below).

The need for a data warehouse at Transcom is mandated by:

- The need of account team supervisors for performance metrics that will assess each agent in the team against minimum standards;

- Regular reports to clients (weekly seems to be the industry norm) to show that service level agreements are being met and the risk of dissatisfaction with customer service is mitigated before widespread damage is done;

- By providing the tool to build Business Intelligence, correspondingly, data warehousing improves decision-making and generates a competitive advantage for Transcom ( Schnur, 2008).

- Merging and prioritizing account activity over the multiple channels shown in Figure 3;

- Collating and synthesizing the sheer volume of information generated for every agent or account team day after day.

- Enabling table formats and graphic views pertinent to the needs of each account.

- Creating BI ‘dashboards’ that give supervisors and managers visibility to performance metrics in real-time.

- Enforcing an outward-looking approach to performance assessment – versus other account teams, in-country sites and other national markets within the Transcom umbrella – rather than the team-centric and parochial view supervisors tend to adhere to.

- Prodding planners and decision-makers to try a variety of query, reporting, multidimensional databases, online analytical processing (OLAP) tools, DW, data mining, and web-enabled reporting capabilities to gain new insights and act on them more speedily.

- Giving country managers the ability to compare performance across multiple sites on a regular basis and Transcom Global head office inter-country facts and trends, plainly impossible with the standalone systems currently in place.

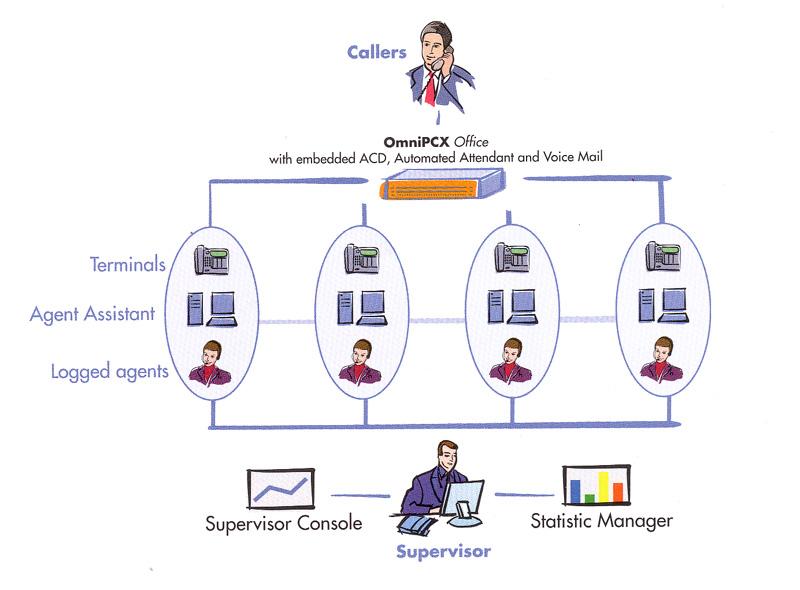

By way of example, every Transcom contact center is already equipped with an Automatic Call Distribution (ACD) system to absorb and route multiple incoming calls to the first free agent. Though call centers are averse to compiling and disclosing the blocking rate to clients, every ACD can be programmed to provide the information. The reason is that SL may indeed reach 99% if 9,900 were taken care of among 10,000 who waited, say, 90 seconds or even longer while hearing a ringing tone. But if, in reality, a total of 12,000 had dialed their credit card company toll-free cardholder assistance “hotline” but 2,000 had gotten a busy signal, then that means the real BR was not 1% but no fewer than 16.7%. One in six disgruntled cardholders reached no one and were therefore frustrated (Bergevin, 2005).

Bibliography

Bergevin, R. (2005) Call centers for dummies: Your guide to profitable call center management. Missisauga, ONT., John Wiley & sons.

Eastbay (2009) Online traffic calculators. Web.

Expertflow (n.d.) Reasons for having a call center. Web.

Holman, D., Batt, R. & Holtgrewe, U. (2007) The global call center report: International perspectives on management and employment.

MIPC/Matrix IP (n.d.) Products and services. Web.

Schnur, K. (2008) Business intelligence/data warehouse [Internet], University of Wisconsin-Stout. Web.

Transcom (2009a) About Transcom United Kingdom. Web.

Transcom (2009b) Transcom Corporate Fact Sheet. Web.

Transcom (2009c) 2008 Annual Report and Accounts. Web.