Executive summary

The present paper overviews IKEA’s internationalisation path that started in the 1980s – about forty years after its establishment. The author seeks to explain what justified the Dutch company’s expansion into foreign markets by applying the so-called OLI paradigm. The OLI paradigm demonstrates that IKEA used its “Democratic design” as a key-value to propose abroad (ownership), reaped benefits from moving its production (location) and guarded its original know-hows (internalisation). Interestingly enough, contrary to Porter’s views, IKEA is an example of a company that focused on both cost leadership and differentiation and did so successfully. Besides, its thoughtful balance of standardisation and localisation gained the trust of consumers in such complex markets as China.

Over the years, IKEA has become an efficient franchisor, which is reflective of its values of entrepreneurial spirit and prioritisation of financial stability. However, at times, franchisees caused legal problems for IKEA, proving that this entry mode is indeed characterised by the lack of control on the franchisor’s part. Lastly, the Dutch company is an example of a large corporation with a strong vertical differentiation, which gives the system a certain rigidity. IKEA seeks to address the said rigidity through its democratic corporate culture enforced in all operation markets.

Introduction

IKEA is a Dutch multinational enterprise (MNE) that develops and sells ready-to-assemble furniture pieces, home accessories, kitchen appliances, and other household goods with occasional home services. The MNE was founded in 1943 in Sweden and, by 2008, had become the world’s largest furniture retailer. As of 2019, there were 433 IKEA stores operating in 52 countries. The average yearly revenue generated from selling goods is 41.3 billion US dollars or 45 billion euros. The company has been successful with diverting part of its sales online. At present, IKEA’s official website contains more than 12,000 products and attracts as many as 2.1 billion visitors every year.

Lutz (2015) writes that upon closer look, it becomes apparent that IKEA owes its success to its thoughtful positioning and marketing. The company made the process of buying furniture and household items not only less burdensome but actually quite entertaining. Lutz (2015) points out how IKEA turned its stores into destinations and attractive places not only for shopping but also for leisure.

The Dutch MNE was able to strike a chord with younger consumers by proposing clean designs, building an image of corporate responsibility and offering goods at an affordable price. Of course, like any other business, IKEA has not been impervious to failures and disappointing ventures. Some of the most memorable and didactic ones are the disastrous entrance in the American market and the launch of the entertainment center with a built-in TV (Petty, 2017).

Today, IKEA is a global phenomenon whose success story has yet to be repeated by other furniture companies. It is apparent that IKEA owes its growth and popularity to the thoughtfully selected internationalisation path, which will be discussed in this paper. Typically, becoming an MNE is associated with many additional costs, issues and challenges. They include but are not limited to working languages and time zones, working around a different and often worse legal structure, maintaining long-distance communication, and handling costly shipping.

This analysis includes a theoretical review that elucidates the particularities of the OLI (ownership-location-internalisation) paradigm that was first proposed by Hymer and later developed by Dunning. The chosen paradigm justifies the decision of a company to turn into a multinational enterprise (MNE) and explains the necessary predispositions and requirements for becoming one. The respective subsection focuses on the three main components: ownership, location and internalisation.

IKEA is a prime example of a company that has successfully combined two opposing foreign corporate strategies: standardisation and localisation. The respective subsection of this paper overviews the case of China, where IKEA has been building its presence since 1998. The Dutch company was able to transfer its values and keep the original designs while accommodating the lifestyle of the average Chinese citizen. The subsection also demonstrates how IKEA was able to strike a balance between cost leadership and differentiation: essentially, it offered original solutions to household furnishing and maintenance at an affordable price.

The primary foreign market entry mode of IKEA is franchising, which is reflective of the company’s values: an entrepreneurial spirit and financial stability. The respective subsection of this paper discusses the case of IKEA franchisees in Turkey. The case confirms the theory of franchising that shows that this mode of entry puts a company at risk of a loss of control. Lastly, IKEA’s organisational structure has also played a role in allowing the company to become international. As of now, the IKEA structure can be categorised as hierarchical, reflecting the massive size of the business that integrates 400 IKEA stores in more 52 markets. Vertical hierarchical structures are often characterised by poor communication and disintegration, which IKEA seeks to overcome by enforcing corporate culture.

Theoretical Review

Internationalisation Theories

As compared to a firm that only operates domestically, i.e., in one country, an international company expands to multiple markets and, therefore, faces unique costs and difficulties. For instance, a company on its way to becoming multinational has to adapt to other working languages and time zones, work around a different and often worse legal structure, maintain long-distance communication and handle costly shippings. The question arises as to why a company would decide to go international given the challenge of doing so. It is true that there are other workable options available: strengthening its position on the domestic market, becoming a supplier for foreign brands, or outsourcing to third parties.

Under the supervision of Kindleberger, in 1969, the Canadian economist Hymer explained and justified the internationalisation of companies by outlining the so-called ownership advantage. The researcher strayed away from the dominant neoclassical paradigm and departed from the notion of the perfect market structure (Strange, 2018). What Hymer proposed instead is to view the market’s imperfections as the impetus behind starting conflicts, fueling competition and gaining advantages (Strange, 2018).

One such advantage described by the Canadian economist is the ownership advantage or ownership condition. In order to outweigh the additional costs of going international, a company needs to own an asset that provides a great value. Some of the examples of such assets are a blueprint, a patent, or copyright: simply put, anything that other contenders cannot copy and offer to the target audience.

The work of Hymer has found successors, the most prominent of which is Dunning. Dunning expanded the concept of ownership advantage to build the OLI paradigm, which stands for ownership-location-internalisation (Sharmiladevi, 2017). Dunning pondered that moving production overseas provides a location advantage, and that, in turn, allows a multinational enterprise (MNE) to spare paying tariffs and shipping costs.

Besides, in some countries, low-skilled labor is extremely cheap, which shrinks a company’s expenses further. The internalisation advantage implies that by refusing to license production to an outside supplier, a company has better chances to protect its blueprints and patents. Despite being fairly recognised in the business world, the OLI paradigm has not escaped criticism (Chowdhury, 2015). In particular, Hymer’s and Dunning’s theories have been questioned because they failed to explain the role of managers and the dynamic evolution of the MNEs.

International Corporate Strategies

Given the costs and challenges associated with internationalisation, it is only reasonable for a company to develop a comprehensive and thorough strategy. In 1980, the American academic and economist Porter proposed the theory of generic strategies. Generic strategies reflect the choices made by an MNE regarding both the type of advantage that it wants to juxtapose to its contenders and the scope of influence. According to Porter, there are three main advantages that an MNE might want to concentrate on: low costs, differentiation and focus (Raksha, 2015). Porter’s ideas have been criticised for his insistence on focusing on one out of two strategies: low cost or differentiation. Today, it is suggested that for some MNEs, it is possible to both build cost leadership and differentiate their products or services, or in other words, find a middle ground.

The theory can be generalised using the following statements:

- If a company is reaching its target audience in most or all segments of a market based on offering the most affordable price, its key strategy must be cost leadership;

- If a company targets customer in most or all segments by capitalising attributes other than prices such as higher product quality, service, or unique design, it is employing a differentiation strategy. These attributes command a higher price, and since they provide an added value, consumers might as well agree to pay more and benefit the company;

- If a company prioritises market segmentation and puts effort into marketing goods to one or a few segments, it is pursuing a focus strategy.

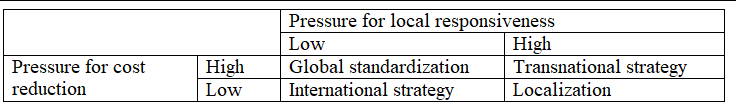

While the aforementioned statements apply to MNEs, there should be made some adjustments to show how they streamline their strategies overseas. There are four basic international corporate strategies that vary in terms of pressures for local responsiveness and pressures for cost reductions (Rizea, 2015) (see Table 1):

- global standardisation pursues low-cost strategy on a global scale and avoids customisation;

- localisation, or customisation, requires higher local responsiveness but not cost reductions;

- a transnational strategy is the most reasonable when pressures for both local responsiveness and cost reductions are high;

- international strategy implies centralising research and development at home and manufacturing locally (low pressure for cost reductions and low local responsiveness).

Foreign Market Entry Theories

Table 2. Foreign market entry modes and their characteristics.

Among foreign market entry modes, experts describe indirect and direct strategies. Indirect strategies are indirect/direct exporting, licensing, franchising and contractual agreements (see Table 2). Direct strategies include joint ventures and wholly-owned subsidiaries/ greenfield investments (see Table 2). Further on, this section will discuss franchising in more detail as it is the foreign market entry mode that is the most appropriate for conceptualising IKEA’s strategy. Franchising is defined as a business model in which a franchiser licenses its blueprints, know-how, intellectual property, procedures, business methods and the rights to sell to a franchisee.

Some of the advantages of the franchise business model are the provision of leveraged growth and development as well as entrepreneurial flexibility. In its interpretation of the theory of franchising, the American researcher Mishra (2017) shows that it is the appropriability of the business model that determines if this decision makes sense or not. Mishra (2017) explains that companies with higher inventory turnover and lower labor intensity are less motivated to franchise their outlets. On the contrary, when faced with the uncertainty of appropriability, companies are more likely to seek potential franchisees.

Like any other business model, franchising has its advantages and disadvantages. Hussain, Sreckovic and Windsperger (2018) write that franchising helps to overcome the most common barrier to expansion, which is the lack of capital. Deciding to license its business model to franchisees, a company can escape the risk of debt or the cost of equity. Further, franchising often means higher profitability because franchisees have an incentive to generate more revenues. On the contrary, franchising often means poorer control over outlets: their production, use of the business model and reputation.

Organisational Structure

Organisational architecture is defined as the totality of a company’s organisation, which entails formal organisational structure, control systems and incentives, organisational culture, processes and people. The organisational structure includes the following elements: the formal division of the organisation, the location of decision-making responsibilities and the establishment of integrating mechanisms (Welch, Benito & Petersen, 2007). Researchers describe the three key dimensions of organisational structure: vertical differentiation, horizontal differentiation and integrating mechanisms (Welch, Benito & Petersen, 2007). Further, in this subsection, organisational structure will be discussed in the context of the global standardisation and partial localisation strategies, as they make the most sense when analyzing the IKEA business model.

The degree of vertical differentiation reflects how centralised or decentralised a company is and how the responsibilities are distributed and delegated. A company that decides to go down the standardisation path might want to strengthen centralisation (O’Neill, Beauvais & Scholl, 2016). There exist the following arguments in support of such a decision: centralisation helps with the coordination and integration of operations.

A centralised company can easily make sure that all the decisions across the board are aligned with its mission, vision and relevant objectives. Lastly, it helps to avoid the duplication of activities carried out by different subunits. Horizontal differentiation is reflective of how a company decides to organise its same-level subunits on a global scale (Christensen, Lægreid & Rovik, 2020). Standardisation is typically associated with worldwide product divisions, which is relevant for the company analyzed. Companies that have chosen standardisation are likely to have many integration mechanisms such as knowledge networks and corporate culture.

An Assessment of the Corporate and Functional Strategies

IKEA’s Internationalisation Strategies

The most applicable paradigm in the case of IKEA is Dunning’s OLI paradigm. Further on, IKEA’s internationalisation path will be conceptualised within the said paradigm:

Ownership

As stated on the IKEA official website, the key concept behind production, research and development is “Democratic design.” The elements of the concept are as follows: a beautiful design, good function, sustainability, good quality and availability at a low price. The uniqueness of “Democratic design” is exactly the value that IKEA owns and that it can propose to customers abroad (“Vision & business idea,” n.d.). Lutz (2015) explains that the Dutch company not only developed interesting solutions but also completely transformed the shopping experience. According to the analyst, before IKEA entered the scene, shopping for furniture used to be burdensome and anxiety-inducing.

The company introduced the concept of ready-to-assemble pieces putting which together would give buyers an extra feeling of self-accomplishment. On top of that, IKEA built a lifestyle philosophy drawing on the ideas of hygge: a slow mode of living with a focus on enjoying little things (“Vision & business idea,” 2011). Hygge was novel to North America and some European and Asian countries with fast-paced lifestyles, which made this philosophy especially attractive.

Location

Moving part of its production overseas benefitted IKEA in the long run. For instance, at first, the Dutch company tried to export goods to China. However, they soon discovered that because of the shipping, the price was not exactly comfortable for the average Chinese citizen (“IKEA in China: big furniture retail adapts to the Chinese market,” 2020). For this reason, IKEA opened several factories in China to manufacture furniture and household utilities locally and maintain cost leadership in the country.

Internalisation

Becoming a multinational enterprise allowed IKEA to keep its know-how and blueprints within the company, which could have been compromised had the company chosen to outsource to third parties. A prime example of enforcing internalisation is IKEA’s policies in China. Lee (2011) writes that when the company just entered the Chinese market, it discovered that local retailers started to copy its format. They used the same color schemes, maze-like zonation, miniature pencils and mockup rooms (Lee, 2011). After this, IKEA improved the secrecy of its blueprints and stopped distributing catalogs to China (Lee, 2011). In summation, IKEA chose to become an MNE because it had original ideas to offer, could benefit from moving production elsewhere and wanted to guard the confidentiality of its developments.

IKEA’s International Corporate Strategy: A Recent Example

A topic that dominates the literature on internationalisation and marketing is standardisation vs. adaptation from a company’s point of view. In this regard, IKEA is a prime example of a multinational enterprise that has gone very far while adhering to standardisation with only partial localisation. Probably, the briefest and concise description from the IKEA official website that allows gaining an insight into its strategy is as follows: “IKEA offers a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible can afford them (“IKEA mission and vision statement analysis,” 2019).”

From this formulation, it becomes apparent that IKEA combines the two generic advantages put forward by Porter: price leadership (“at prices so low that as many people as possible can afford them”) and differentiation (“well-designed, functional home furnishing products”). IKEA makes it a point to work in the same way and build the same image in all countries that it operates in. Arguably, this decision gives the Dutch company various operational advantages and allows it to keep prices relatively low and attractive.

China is a prime example of IKEA combining standardisation and localisation as well as finding a middle ground between cost leadership and differentiation in a way that lower costs do not subtract from quality. IKEA entered the Chinese market in 1998 when it opened its first store in Shanghai (“IKEA in China: big furniture retail adapts to the Chinese market,” 2020). Soon enough, the company ran into the same problems that it had with other overseas markets: Chinese living conditions were different from those normal for European countries. IKEA struck a balance by retaining the original designs and brand imagery (stylish, Scandinavian furniture) and adapting the size and modularity to fit smaller Chinese apartments.

At first, the Western brand was primarily attracting younger audiences between ages 20 and 35 that apparently, were more sensitive to foreign trends and influence (“IKEA in China: big furniture retail adapts to the Chinese market,” 2020). However, after a few years since the official launch, IKEA witnessed growing popularity with the population over 45 who started trusting the corporation more.

Building and maintaining cost leadership in China was another challenge to be faced. Soon after the entry, IKEA discovered that while its prices were considered low by North Americans and Europeans, for Chinese customers, they were barely affordable (Lingxiu, 2017). The Dutch company was risking significant losses, and still, it decided to go through with cost reductions, which is consistent with the theory outlined in the previous section.

Besides, IKEA had to make readjustments to complement the average Chinese customer’s lifestyle (Lingxiu, 2017). In Europe, IKEA stores were mostly located in the suburbs next to metro stations and were overall designed to be accessible by car. In China, the company settled on constructing buildings on the outskirts next to railway stops because the Chinese were primarily reliant on public transportation. In summation, IKEA brought its original blueprints and designs to China to attract customers and retained them with its readjustments to their lifestyle.

IKEA’s Foreign Market Entry Strategy: A Recent Example

One of the primary foreign market entry strategies employed by IKEA is franchising. On its official website, the company explains that the decision to franchise its business model was motivated by the desire to offer IKEA products to as many customers as possible. Ever since the early 1980s, when the company just started its global conquest, its founder Ingvar Kamprad was concerned about two things: fostering and nourishing the entrepreneurial spirit and conserving the original concept.

A franchise system was seen as one of the pillars for ensuring the long-term growth and development of the Dutch company. Franchising has the potential of providing greater financial stability while allowing franchisees to push their limits, test new ideas, explore new markets and reach out to wider audiences. This attitude is reflected in the following statement by Kamprad: “From the very start, our aim has been to create the greatest possible financial security for employees and for the various groups of IKEA companies (“The IKEA franchise system,” n.d.).”

Turkey is an example of a country where IKEA stores operate under a franchising agreement. As any potential franchisees, Turkish applicants were evaluated by Inter IKEA Systems B.V. Once they were chosen, an agreement was signed, with which the franchisees were granted the right to operate IKEA stores and sell goods through approved channels using pre-established methods. Today, the Dutch company has opened six stores in Turkey, all under franchising agreements. The contract is mutually beneficial: IKEA franchisees pay 3% of their annual net sales to Inter IKEA Group, and in return, they receive access to the company’s trademarks.

The franchise system in Turkey has accounted for steady growth: it allowed the company to develop its concept, lay a solid foundation and strengthen its presence in the Asian country. Because several successful franchises all over the country increased overall sales, IKEA was able to keep the prices in Turkey low enough to be affordable for middle-class consumers. On the contrary, the franchising system in Turkey has shown its pitfalls as well. As it has been mentioned in the previous section, a franchiser puts itself at risk of losing control over franchisees, which, unfortunately, happened to IKEA eight years ago.

In 2018, the Dutch company found itself in the middle of a workers’ right controversy: it turned out that IKEA Turkey was blunting employees’ attempts to organise into a union. Respecting workers’ rights is one of IKEA’s priorities, which is why the company had to take legal action against its franchisee.

IKEA: Organising for the Strategy

As compared to other retailers, it is safe to say that IKEA has a unique organisational structure. In particular, around the world, a large number of companies are operating under the IKEA brand, but all IKEA franchisees retain their independence from Inter IKEA Group. Quite a big share of franchises are owned and operated by INGKA Group. It should be noted that IKEA and INGKA Group were founded by the same person and share a common history and heritage. However, since 1980, the corporations have been operating under different owners and management (“Company information,” n.d.).

As for horizontal differentiation, IKEA has many global divisions whose independence is associated with the selected mode of entry into the respective market (for instance, less independence for joint ventures and more freedom for franchisees). Inter IKEA Group integrates a group of companies that include:

- Inter IKEA Systems B.V. is a worldwide franchisor that handles franchise agreements with 12 franchisees in 52 markets;

- IKEA Range & Supply is responsible for the supply and development of products in the home improvement and furnishing chain;

- IKEA Industry is the key producer of home furnishing products and the manufacturer behind 10-12% of the total range (“Company information,” n.d.).

Vertical hierarchical structures that are typical for large corporations such as IKEA have their own set of challenges. First and foremost, given the large number of countries that IKEA operates in, there might be issues with communication and transfer of ideas and solutions. The Dutch company seeks to mitigate these difficulties by establishing a strong corporate culture. On its official website, IKEA writes that it prioritises democratic values and nurtures the atmosphere of mutual support (“Culture & values,” n.d.). The company works hard to ensure that each outlet respects diversity in the workplace and ensures equality of all people.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Today, IKEA is a global phenomenon and the most successful furniture retailer in the world. Starting in the 1980s, IKEA has been aggressively expanding into foreign markets and, as of now, has more than 400 stores operating in 52 countries. The success of IKEA can be explained through the so-called OLI paradigm that was first developed by the Canadian economist Hymer and further expanded by Dunning. It seems that IKEA has successfully pinpointed the kind of value that it had to add to customers’ experience (“Democratic design”). It also addressed the issues of cost leadership wisely by moving its production to target markets. However, at the beginning of its internationalisation path in China, it had problems with the internalisations of know-how and blueprints.

The foreign corporate strategy of IKEA is a prime example of how a large corporation can keep a recognisable image and original branding while appeasing customers’ diverse tastes. The entry mode (franchising) is in line with IKEA’s key values, even though, on some occasions, it proved to be problematic because of the poor control over franchisees. Lastly, the Dutch company is a trailblazer of the democratisation of corporate culture that puts together a rigid, hierarchical structure.

Despite the so far almost flawless history of success, IKEA might face challenges entering new markets and strengthening its position in the countries where it has already operated for a while. For Western countries, IKEA might have to position itself against two trends: online shopping and originality. In the era when customers can get anything in two clicks, spending a day at a suburban IKEA store might seem burdensome. Therefore, IKEA might want to enhance the online shopping experience and introduce customisable models instead of cookie-cutter solutions. As for emerging markets, IKEA might have to tip the balance between standardisation and localisation toward localisation to gain the locals’ trust.

Reference List

Chowdhury, AK. (2015). The theory of multinational enterprises: revisiting eclectic paradigm and Uppsala model, Business and Management Horizons, 3(1), 72-79.

Christensen, T, Lægreid, P & Rovik, KA. (2020). Organization theory and the public sector: instrument, culture and myth, Routledge.

Company information. (n.d.). Web.

Culture & values. (n.d.). Web.

Hussain, D, Sreckovic, M and Windsperger, J. (2018). An organizational capability perspective on multi-unit franchising. Small Business Economics, 50(4), 717-727.

The IKEA franchise system. (n.d.). Web.

IKEA in China: big furniture retail adapts to the Chinese market. (2020). Web.

IKEA mission and vision statement analysis. Web.

Lee, M (2011) Chinese retailers hijack the Ikea experience. Web.

Lingxiu, J (2017) IKEA marketing entry strategy in China. Web.

Lutz, A (2015) Ikea’s strategy for becoming the world’s most successful retailer. Web.

Mishra, CS (2017) The theory of franchising, in Creating and Sustaining Competitive Advantage (pp. 307-355), Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

O’Neill, JW, Beauvais, LL & Scholl, RW. (2016). The use of organizational culture and structure to guide strategic behavior: an information processing perspective, Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 2(2), 816.

Peker, E & Hansegard, J. (2012). IKEA’s Turkish labor issue. Web.

Petty, A. (2017). The untold truth of IKEA. Web.

Raksha, N. (2015). Competitive strategies as an effective instrument of enterprise development, Ebsco Index, 3(4), 69-76.

Rizea, RD. (2015). Growth strategies of multinational companies, Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiesti Bulletin, Technical Series, 67(1), 59-66.

Sharmiladevi, JC. (2017). Understanding Dunning’s OLI paradigm, Indian Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, 8(3), 47.

Strange, R. (2018). Corporate ownership and the theory of the multinational enterprise, International Business Review, 27(6), 1229-1237.

Vision & business idea. (n.d.). Web.

Welch, LS, Benito, GRG & Petersen, BB. (2007). Foreign operation methods: theory, analysis, strategy. Glos: Edward Elgar Pub.