Week 1: Introduction to Quality

During the first week, the task was to understand the essence of such concepts as service quality and attributes of products. In addition, it was necessary to define competitive advantage and its relation to quality. According to Fernandes et al. (2017), supply chain management (SCM) and quality management (QM) are the concepts that promote competitiveness in organizations. Quality is an important aspect of the relationships that customers and suppliers have to develop (Fernandes et al. 2017).

Therefore, the idea to begin the course with definitions and their connections turns out to be a good step in learning SCM processes. I like the possibility to compare the definitions of quality and investigate the attributes of a product like performance, conformance, and serviceability (Dubey et al. 2019). Deming, Crosgy, and Juan shared similar issues in quality description like attention to commitment, financial benefits, and customer orientation. Still, they different in orientation (technical by Deming, process by Juran, and motivation by Crosby) and methods of achievement. This information is characterized by a number of positive outcomes, developing necessary managerial skills and contributing to future progress.

Today, managers are involved in the creation of multiple strategies to improve their supply chain practices. The potential expectations include the enhancement of competitive advantage and the achievement of superior performance (Datta 2016). In other words, I understand the scheme in the following way: the higher quality of products is, the better outcomes and profits may be observed. The idea of SCM is to establish effective flows and services to support customers and introduce good working conditions. Quality is a standard according to which managers should study and work. As soon as quality aspects are identified, a company is able to succeed in competition at different levels.

Week 2: Quality Management Background

The second week was devoted to the evaluation of QM through the prism of different models and theoretical frameworks. It was interesting to admit that a number of cultural, scientific, and occupational factors determined the progress and effectiveness of QM in various spheres. Deming, Juran, Feigenbaum, Ishikawa, and Taguchi contributed to QM development in modern business (Dahlhaard-Park, Reyes and Chen 2018). Deming was a pioneer in modeling QM activities, who introduced his 14-points philosophy, starting from improvement purposes and ending with transformations (Glykas 2019). Juran added several categories to classify the processes in terms of planning, control, and improvement. The donation of Ishikawa was based on the necessity to respect customers and employees and their societal interests.

The strength of this week is the intention to limit information to the most important aspects. Regardless of a variety of ideas, three main principles (teamwork, improvement, and customer) were identified. Statistical thinking was proved crucial for understanding variations in supply chain management (Lizarelli, Antony and Toledo 2020). However, not to be confused with SCM theories and methods, the worth of ISO 9000 was explained.

The International Standards Organization (ISO) defines such principles as customer focus, leadership, employee engagement, process approach, improvement, evidence-based decision making, and relationship management cannot be neglected (Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek 2016). All these formulas and plans on how to manage supply chain quality turn out to be the result of many scientists’ work, and this course is a good attempt to gain a better understanding of how quality may be improved.

Week 3: Quality with a Customer Focus

Compared to previous weeks where a customer focus was mentioned as a crucial part of SCM and QM, this week aims at discussing the peculiarities of this particular principle. A description of a “customer” was given to clarify who this person could or could not be. In fact, it was defined as a recipient of a product/service who pays for it directly or indirectly and gains certain benefits (Elg, Wihlborg and Örnerheim 2015).

As soon as a company knows what a customer is, its leaders and managers can develop specific relationships and supply chain themes. As cited in Elahi and Ilyas’ study (2019), there are several critical dimensions of this concept, including the level of satisfaction, expectations, and relationships. When all these issues are combined and used to identify the level of expected quality, business success may be observed.

During this week, I was involved in many activities to compare how different organizations work with their clients. Apple and Amazon proved that the role of a customer is crucial, and supply chain management strategies are necessary to obtain competency in delivery services. I have concluded that there are no right or wrong questions about the role of a customer in supply chain business, and this course, along with its models, theories, and methods, shows how to investigate and comprehend customer needs. However, I also know that customers vary in their interests, and the same approach is never effective, so good managers should realize the uniqueness and worth of every client.

Week 4: Achieving Quality Through a Motivated Workforce

There are many ways to develop high-quality services and products, and motivation is one of them. On the one hand, it is expected to motivate customers to buy products and pay attention to services. On the other hand, if employees are not motivated, they can hardly present good work. The central theme of this week was quality achievement through a motivated workforce. As any future employee, a student wants to know about the methods that employers use to attract a new workforce.

This course helps comprehend why workforce engagement and satisfaction are closely related to business success. It is not enough to create a favorable environment and set several goals. It is essential to assess human and organizational capabilities and use special rewards (Péter et al. 2018). I enjoyed the period when I studied the importance of cooperation between leaders, managers, and ordinary workers.

There are many strategies to sustain the workforce and help people meet their professional and personal purposes. Creating an environment for everyone to work at their full potential has to be within the limits of an organization (Kakkar 2019). I want to believe that modern business is based on trust, respect, and autonomy. However, such factors as money (monetary rewards) and family (family support) also matter in quality and supply chain management. I have learned that motivated employees take responsibility for efficiency in the supply chain industry, and motivation is never the same because many things depend on people, their knowledge, and their openness in communication.

Week 5: Achieving Quality Through a Process Focus

This week’s goal was to understand the activities in supply chain management based on a process approach. Isaksson (2019) says that the idea of a process is to deliver value to a customer. Discussing the main QM principles, Deming and Juran underlined the necessity to build a number of processes to produce products/services, achieve results, and enhance communication or information exchange (Dash and Tripathy 2016).

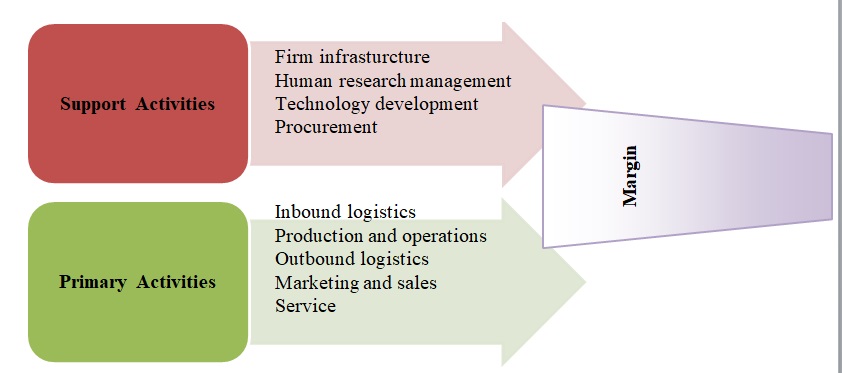

The connection between this management principle and SCM is obvious because any process is an attempt to improve the already offered ideas, transform inputs, and increase competitiveness. I have discovered that a company should follow more than one process management principle (identify values, determine key work, measure opportunities, etc.). An understanding of values is an obligatory step for managers who want to improve their activities and achieve a competitive advantage. During this week, Porter’s value chain model was thoroughly studied as a possibility to map the market and analyze chain actors and relationships (Zamora 2016):

Value chain analysis is illustrated in Figure 1 to underline the importance of support and primary activities and increase margins that lead to competitive advantage. Using this framework, it was discovered that businesses are responsible for making decisions that lead to profitability, mistakes, or changes in competitive positions. Many processes turn out to be the activities that managers, leaders, and local employees have to complete in regard to their resources, goals, and abilities, and this week is a chance to combine practical and theoretical skills.

Week 6: Supply Chain Design for Quality & Product Excellence

I would like to define the wroth of the material studied during this week as an essential part of many supply chain management activities. First, the design process was discussed through the prism of quality and competition in the modern market. Second, illustrative examples were introduced in the form of a product development process (idea generation, preliminary concept development, process development, full-scale production, market introduction, and market evaluation) and the Design for Six Sigma (DFSS) approach. Salam and Khan (2018) explain supply chain excellence as a result of a properly chosen strategic framework for product/service development and delivery. Therefore, I found this week’s focus crucial for my further job.

Managers are free to rely on different principles and activities in developing their supply chain methods. Current achievements and innovations have significantly shaped the quality and variety of service experience, and it is reasonable to use service design thinking in SCM. However, the DFSS approach remains a key factor in achieving management success. Concept development, detailed design, design optimization, and design verification are the four elements. Jenab, Wu and Moslehpour (2018) prove that DFSS should not be considered a methodology but an attitude toward delivering products and services. Therefore, it is wrong to omit a phase or change the order to the steps in this model. Now, I know that my SCM success depends on how well I determine a product need (concept), choose parameters and ensure functionality (design), identify failures and benefits (optimization), and achieve the desired quality level (verification).

Week 7: Measuring and Controlling Quality in the Supply Chain

The goal of this unit is to recognize how quality control can be measured in the supply chain. At this moment, I have learned how to develop effective supply chain process designs and why quality is a major concept in service delivery. Now, it is necessary to describe the methods of how to define wheather all quality measures are followed. First, I learned that measurement includes data collection and analysis to classify product values and processes. Second, one should remember that performance and quality measurement is required at the macro and micro levels, focusing on different contexts (Gunasekaran, Subramanian and Rahman 2017; Tundys and Wi´sniewski 2018).

Attribute measurements show visual examples that have to be inspected, and variable measurements focus on statistics and deviations. Finally, as any management process, measurement is characterized by specific outcomes, which, in this case, comprises quality improvement.

Applying measurements to the supply chain means to find out the balance between cost and quality and maximize available business opportunities. According to Gulc (2017), measuring tools cannot be simply applied to a service sector, and it is required to understand suitable tools and expected level of quality. Therefore, such characteristics as accuracy, stability, reproducibility, and repeatability matter. It was also correct to mention that Deming preferred statistical data to measure performance quality ambiguously (Agrawal 2019). Compared to previous lessons, this week contributed to a better understanding of what defines service quality, how managers measure their work, and why the basics are important to achieve the desired outcomes.

Week 8: Supply Chain Improvement & Lean Six Sigma

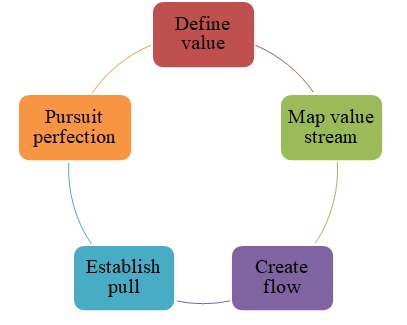

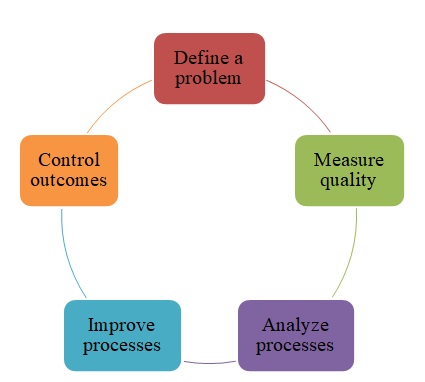

As soon as the main measurement principles and characteristics of supply chain quality management were presented, it was time to learn how to improve the current conditions and what methods are frequently applied. This week was based on the idea that processes cannot become better if managers do nothing to improve them. Many researchers have a similar position that organizations are responsible for their services and productivity (Fourie and Umeh 2017; Nakano and Oji 2017). As a result, new models are developed, and the already approved frameworks are utilized. In the majority of cases, every time an improvement is made, a new (or changed) value is distinguished, and the evolution of Lean, as well as Six Sigma, principles proves the possibility of the creation of credible processes. In Figures 2 and 3, the steps of the approaches are presented (Salah and Rahim 2019):

The process of evolution is evident in the supply chain industry, and it was expected that similarities of the chosen approaches could provoke their integration. This week was used to explain why and how Lean and Six Sigma strategies were combined, following their common processes like concept definition, analysis, and control (measurement) and differences like those in the implementation stage. Lean Six Sigma has become one of the leading business methodologies in SCM that promotes brainstorming, mapping, standardization, and analysis. I find this material necessary to develop new supply chain processes and learn how to correct mistakes and shortages.

Week 9: Excellence in Supply Chain Knowledge Management

At the beginning of this week, the topic of excellence in supply chain knowledge management (KM) was called one of the most complex but necessary issues in the field. It was necessary to introduce KM as an effective response to economic and organizational challenges caused by such processes as globalization and transformation. Raudeliūnienė, Jurgita, Davidavičienė and Jakubavičius (2018) explain KM as an effective tool to increase organizational effectiveness and define companies’ potential in the modern age. Abubakar et al. (2019) underline the importance of making correct decisions and demonstrating outstanding performance. Therefore, this week creates a solid foundation for a KM perspective, using the studies in sociology, psychology, philosophy, and economics.

Students have learned that KM is a systematic form of management, and there are six main aspects. As a future supply chain manager, I should know how to gather and share relevant knowledge, which is why I need a strategy. The next step is the creation of organizational culture in terms of which people need to cooperate. All organizational processes must be discussed, and effective leadership is a requirement.

Finally, KM depends on how well technologies and corporate politics are applied. Using the examples of maritime/logistics supply chains, Kalogeraki et al. (2018) proved that the application of KM strategies improves many processes and includes a variety of autonomous players, who have to be motivated and coordinated. Therefore, the KM system that is learned during this week represents a clear plan with important tasks for leaders in the supply chain.

Week 10: Leadership for Supply Chain Quality Management Excellence

Many factors determine the quality of employee work and services that clients use. However, if I were asked about who performs a central role in business success, my answer would be “a good leader.” Therefore, the week during which leadership for SCM excellence has to be studied was one of the most expected units in this course. I wanted to know what identifies a good leader and why many modern organizations prefer to focus on customers or managers instead of understanding leadership qualities (Luo, Shi and Venkatesh 2018). In fact, the theme of leadership is too broad, and it was difficult to choose one course and follow it precisely.

There are many leadership styles that people prefer, relying on their knowledge and qualities. Leadership theories have to be employed to characterize people and their contributions to organizational excellence (Mokhtar et al. 2019). For example, the Great Man Theory helps me realize that some leaders are born, not made, and their capacities are innate not obtained with time. Although I am not a supporter of this idea, I like to think that some people do not need to study to do great things. Many other theories that are based on traits, skills, and situational approaches prove the necessity to focus on particular aspects of leadership. Personally, I prefer a transformational theory according to which leaders cooperate and develop along with a team. This method is effective in the supply chain as it promotes continuous improvement and information exchange at all levels.

Week 11: Building and Sustaining Supply Chain Success

The last week of the course aims at gathering and analyzing all the material mentioned in previous weeks. However, in addition to assessing the level of knowledge from past studies, it was also expected to make final improvements in understanding what promotes supply chain success. The contributions by Edgar Shein (2019) were discussed because this person admits the necessity of a new model (culture) to build professional relationships on openness and trust. In the supply chain, organizational culture defines how all work has to be done and how different beliefs and values shape group relationships.

However, because of network expansion, competitive global markets, lack of support, and managerial complexity, it becomes difficult to achieve an organizational culture in the supply chain. Therefore, to solve problems and achieve success, contemporary SCM strategies should be identified. First, it is necessary to remember critical success factors (customer focus or leadership), implement supply chain competence (quality product or delivery reliability), and make strategically competent decisions (optimization or technology management).

At the end of the course, I feel that I know a lot to sustain supply chain success by focusing on specific SCM goals and frameworks. I like the approach by Rajabion et al. (2019) about knowledge sharing as one of the most effective SCM mechanisms to improve employee performance, promote innovation, increase competitive advantage, and stabilize human relationships. This course shows that it is never too late to study and build new models, relying on constantly changing factors in the supply chain and skills.

Reference List

Abubakar, Abubakar Mohammed, Hamzah Elrehail, Maher Ahmad Alatailat, and Alev Elçi. 2019. “Knowledge Management, Decision-Making Style and Organizational Performance.” Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 4 (2): 104-114. Web.

Agrawal, Nichant Mukesh. 2019. “Modeling Deming’s Quality Principles to Improve Performance Using Interpretive Structural Modeling and MICMAC Analysis.” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management. Web.

Dahlgaard-Park, Su Mi, Lidia Reyes, and Chi-Kuang Chen. 2018. “The Evolution and Convergence of Total Quality Management and Management Theories.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 29 (9-10): 1108-1128. Web.

Dash, Aishwarya and Sushanta Tripathy. 2016. “Journey of Quality Management Practices Towards 21st Century.” International Journal of Management & Business Studies 6 (2): 14-19.

Datta, Partha Priya. 2016. “Enhancing Competitive Advantage by Constructing Supply Chains to Achieve Superior Performance.” Production Planning & Control 28 (1): 57-74. Web.

Dubey, Prince, Naval Bajpai, Sanjay Guha, and Kushagra Kulshreshtha. 2019. “Entrepreneurial Marketing: An Analytical Viewpoint on Perceived Quality and Customer Delight.” Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 22 (1): 1-19. Web.

Elahi, Fazal, and Muhammad Ilyas. 2019. “Quality Management Principles and School Quality: Testing Moderation of Professional Certification of School Principal in Private Schools of Pakistan.” The TQM Journal 31 (4): 578-599. Web.

Elg, Mattias, Elin Wihlborg, and Mattias Örnerheim. 2015. “Public Quality–For Whom and How? Integrating Public Core Values with Quality Management.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 28 (3-4): 379-389. Web.

Fernandes, Ana Cristina, Paulo Sampaio, Maria Sameiro, and Huy Quang Truong. 2017. “Supply Chain Management and Quality Management Integration.” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 34 (1): 53-67. Web.

Fourie, Cornelius Jacobus, and Nicholas E. Umeh. 2017. “Application of Lean Tools in the Supply Chain of a Maintenance Environment.” South African Journal of Industrial Engineering 28 (1): 176-189. Web.

Glykas, Michail. 2019. “Quality Management Review: A Case Study of the Application of the Glykas Quality Implementation Compass.” Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology 6 (12): 11260-11279.

Gulc, Aleksandra. 2017. “Models and Methods of Measuring the Quality of Logistic Service.” Procedia Engineering 182: 255-264. Web.

Gunasekaran, Angappa, Nachiappan Subramanian, and Shams Rahman. 2017. “Improving Supply Chain Performance Through Management Capabilities.” Production Planning & Control 28 (6-8): 473-477. Web.

Isaksson, Raine. 2019. “A Proposed Preliminary Maturity Grid for Assessing Sustainability Reporting Based on Quality Management Principles.” The TQM Journal 31 (3): 451-466. Web.

Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek, Małgorzata. 2016. “ISO 9000: 2015 Quality Management Principles as the Framework for a Maintenance Management System.” Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Poznańskiej 69: 49-65. Web.

Jenab, Kouroush, Cuibing Wu, and Saeid Moslehpour. 2018. “Design for Six Sigma: A Review.” Management Science Letters 8 (1): 1-18. Web.

Kakkar, Sandeep. 2019. “Important Factors Motivating the Workforce: A Study of IT Startup.” Think India Journal 22 (15): 303-316.

Kalogeraki, Eleni-Maria, Dimitrios Apostolou, Nineta Polemi, and Spyridon Papastergiou. 2018. “Knowledge Management Methodology for Identifying Threats in Maritime/Logistics Supply Chains.” Knowledge Management Research & Practice 16 (4): 508-524. Web.

Lizarelli, Fabiane Leticia, Jiju Antony and Jose Carlos Toledo. 2020. “Statistical Thinking and Its Impact on Operational Performance in Manufacturing Companies: An Empirical Study.” Annals of Operations Research. Web.

Luo, Wen, Yangyan Shi, and Venkataswamy Gurusamy Venkatesh. 2018. “Exploring the Factors of Achieving Supply Chain Excellence: A New Zealand Perspective.” Production Planning & Control 29 (8): 655-667. Web.

Mokhtar, Ahmad Rais Mohamad, Andrea Genovese, Andrew Brint, and Niraj Kumar. 2019. “Supply Chain Leadership: A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda.” International Journal of Production Economics 216: 255-273. Web.

Nakano, Mikihisa, and Nobunori Oji. 2017. “Success Factors for Continuous Supply Chain Process Improvement: Evidence from Japanese Manufacturers.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 20 (3): 217-236. Web.

Péter, Erzsébet, Kornél Németh, Andrea Katona, Nikoletta Göllény Kovács, and Ildikó Lelkóné Tollár. 2018. “Skilled and Motivated Workforce – The Key to Success Promises, Expectations.” Pannon Management Review 7 (4): 9-33.

Rajabion, Lila, Amin Sataei Mokhtari, Mohammad Worya Khordehbinan, Mansoureh Zare, and Alireza Hassani. 2019. “The Role of Knowledge Sharing in Supply Chain Success.” Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology. Web.

Raudeliūnienė, Jurgita, Vida Davidavičienė, and Artūras Jakubavičius. 2018. “Knowledge Management Process Model.” Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 5 (3): 542-554. Web.

Salah, Souraj, and Abdur Rahim. 2019. “Introduction and Overview: Combining Lean Six Sigma with Process Improvement.”International Journal of Lean Six Sigma 1 (3): 249-274. Web.

Salam, Mohammad Asif, and Sami A. Khan. 2018. “Achieving Supply Chain Excellence Through Supplier Management.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 25 (9): 4084-4102. Web.

Schein, Edgar H. 2019. “A New Era for Culture, Change, and Leadership”. MIT Sloan Management Review 60 (4): 52-58. Web.

Tundys, Blanka, and Tomasz Wi´sniewski. 2018. “The Selected Method and Tools for Performance Measurement in the Green Supply Chain – Survey Analysis in Poland.” Sustainability 10 (549). Web.

Zamora, Elvira A. 2016. “Value Chain Analysis: A Brief Review.” Asian Journal of Innovation and Policy 5 (2): 116-128.