The soft drinks sector is considered one of the most competitive markets in the food industry. It has a relatively low barrier of entry, wide availability of technologies that enable local producers to compete with international brands, and low requirements for research. Due to relative parity in taste and quality, many companies are forced to compete using non-economic methods. Yet, at the same time, this market has two leaders that establish the rules of competition.

The cola market is considered the largest in the soft drinks sector due to cola being the most favored and widely-recognized carbonated beverage in the world. This market is dominated by two competing giants: Pepsi and Coca-Cola. Together, these companies have a market share of roughly 70-75%, with Coca-Cola’s share being around 45% versus Pepsi’s 30% (Cotterill, Putsis, Rabinowitz, & Druckute, 2015). The presence of two large competitors that shape the industry is known as an oligopoly market. The purpose of this paper is to provide an economic analysis of these two giants through the prism of oligopoly with the perspective for the 21st century.

Strategic Behavior of Pepsi and Coca-Cola

An oligopolistic system of competition is defined by the mutual interdependence of all large companies engaged in the vigorous competition (Krishnendu, 2017). The amount of profits and market share of both companies depends not only on prices but also on the immediate reactions of one’s direct competitors. Coca-Cola and Pepsi produce roughly the same product of the same color and the same taste. They are widely popularized in the market.

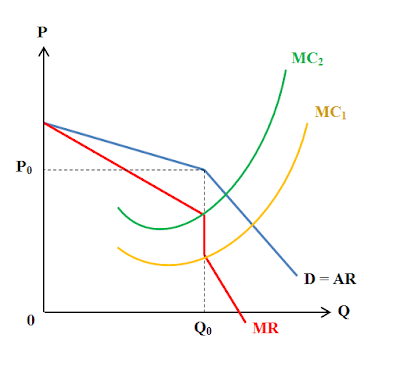

An oligopoly operates on two assumptions. The first assumption is that if a company increases the price of their product, the competition will not do the same, because they are expecting an increase in sales and market share, which would bolster their profits in the short and long-term perspectives (Krishnendu, 2017). However, if a company chooses to drop its prices, the competition would follow to prevent their customers from switching to the opposing brand. The relationship between prices in an oligopoly is demonstrated in the following graph:

As shown in Figure 1, the price loses its elasticity beyond P0. If both Coca-Cola and Pepsi decrease their prices together, the demand remains static. The appearance of the demand curve unique to oligopolistic markets and cannot be applied to a perfect competition model. The price of the product is always higher than the marginal costs, which makes the profit maximization rule used in perfect competition models inapplicable as well.

Since Coca-Cola and Pepsi are the main powers that control the industry, they can set the price higher than the marginal costs without losing any market share. In addition, this system is not productively efficient when compared to the perfect competition, where P is calculated using the following formula: P=min ATC (Yanagihara & Kunizaki, 2016). It enables both Coca-Cola and Pepsi to receive supernormal profits in the long run by restraining output and matching the competitor’s price. Thus, the concept of mutual interdependence revolves around Coca-Cola and Pepsi reacting to each other’s price changes. Since each company is capable of matching another, the strategy of beating the competition with lower prices ends up in a stalemate.

Fair Elasticity of Prices

Even though Coca-Cola and Pepsi products are nearly identical in terms of quality and taste, the price for these products is not perfectly elastic. The concept of perfect elasticity states that customers are highly sensitive to prices and will not hesitate to switch brands should one company increase prices even by a tiny margin (Krishnendu, 2017). However, there is a possibility to effect this elasticity and reduce it by affecting the customers’ perceptions of the product and growing customer loyalty.

For example, the current situation shows that although in the event of a price increase for Coca-Cola products most customers would switch to Pepsi over Coke, a portion of customers would remain loyal to the brand. Thus, although the number of sales would decrease, it would never reach Zero, resulting in fair, but not perfect elasticity (Krishnendu, 2017). Both companies experience cross-elasticity due to similarities in products, as the majority of customers would switch between Coca-Cola and Pepsi products based on the price tag alone.

Non-Price Ways of Competition

Since it was proven that both companies could match each other in price, quantity, and quality of the product, Coca-Cola and Pepsi engage one another in non-price competition. To gain an advantage, both companies use extensive advertising campaigns to promote their brands, generate customer loyalty, and highlight the small differences between their products. The expenditures made by both companies to advertise their product are the reason the demand curve is shifting to the right, which results in the gradual growth of price and output for both products (Otuki, 2013).

Coca-Cola and Pepsi have different strategies of competition. Pepsi focuses on promoting its products by hiring celebrities to endorse their products. Some of the celebrities enrolled in Pepsi’s advertising campaign were Madonna, Beyoncé, and Britney Spears (Otuki, 2013).

Coca-Cola, on the other hand, makes its bid on careful studying of the market and generating greater exposure by coming closer to the people. Some of the more innovative moves included the introduction of “Happiness Machines,” where customers received random gifts ranging from flowers to pizza, along with their cola (Allen, 2015). In addition, Coca-Cola is looking to differentiate its products based on the lower amounts of calories and sugar in their products.

In 2010, they launched a new product called “Diet Coke,” which managed to grab a large portion of the diet soft drink market (Koschmann & Sheth, 2016). Pepsi did try promoting a similar product in 1993, but improper timing resulted in a marginal failure. In 2010, however, Coca-Cola’s move enabled it to triple the number of sales on Pepsi, the total sales being in 2.5 billion bottles for both products vs. 0.9 billion for Pepsi alone (Koschmann & Sheth, 2016). This helped secure a greater market share for Coca-Cola over Pepsi. However, since the soft-drink industry is relatively slow on innovation, Pepsi entrenched itself in its current market share positions and is content with holding its market share and prepare for the next Cola Wars.

Conclusions

Competition between Coca-Cola and Pepsi in the 21st century serves as a perfect example of oligopoly economics. Although nearly any soda company is capable of producing cola of similar quality and at a similar price, Coca-Cola and Pepsi are the most recognizable companies in the market and control most of their shares. While the competition results in frequent promotional efforts, price drops, and other venues that benefit the customer, the existence of these companies set a high entry barrier for newcomers, as it is very hard to claim any significant market share. Thus, while an oligopoly offers a greater choice when compared to a monopoly, it is still far from instilling fair competition.

References

Allen, F. (2015). Secret formula: The inside story of how Coca-Cola became the best-known brand in the world. New York, NY: Open Road Media.

Cotterill, R. W., Putsis, W., Rabinowitz, A. N., & Druckute, I. (2015). Soft drinks: The carbonated drink industry in the United States. In V. J. Tremblay & C. H. Tremblay (Eds.), Industry and firm studies (pp. 204-244). New York, NY: Routledge.

Koschmann, A., & Sheth, J. N. (2016). Do brands compete or coexist? Evidence from the Cola Wars. Web.

Krishnendu, G. D. (2017). Oligopoly, auctions and market quality. Tokyo, Japan: Springer.

Otuki, N. (2013). Coca-Cola mulls price cut in market battle with Pepsi. Business Daily. Web.

Yanagihara, M., & Kunizaki, M. (Eds.). (2016). The theory of mixed oligopoly: Privatization, transboundary activities, and their applications. Tokyo, Japan: Springer.