Abstract

Decision-making is becoming a very complex phenomenon for managers today. Currently, managers are faced with more complex decisions than any other group of managers before them. However, the battle to sustain and increase organizational profitability still remains arduous in many economic sectors. The sophistication of consumer demands and the ever-growing threat of competition further complicate the realization of organizational objectives. This paper explores how management accounting helps in the decision making process by investigating costing and its antecedents as critical tools in the decision making process.

Particularly, this paper focuses on marginal costing, activity based costing, activity based management, target costing, break-even point analysis and variance analysis as important tenets of management accounting that aid in decision-making. Comprehensively, this paper proposes that management accounting helps to gather all relevant managerial data through different tools such as cost sheets, labor cost reports, overhead utilization reports and the likes.

Using different costing techniques, managers are able to explore the alternatives for decision making using such information. The outcome for this process is better organizational performance and a better understanding of the decision problems. However, the most important contribution of management accounting to managers is its role in helping them merge organizational objectives with organizational activities.

Introduction

Accounting has been traditionally associated with numbers and the management of financial records. Most literatures have similarly referred to management accounting in this regard. However, few researchers have focused on the importance of accounting as a management tool. Indeed, it is through the importance of including accounting in the decision-making process that management accounting was birthed. Ideally, management accounting is supposed to provide the groundwork for making important decisions in an organization because management accounting provides the knowledge of history which is important for making future company decisions (Chadwick 1998).

To determine the status of the current and future states of management accounting, it is therefore crucial to explore the history and development of management accounting. The investigation into the history of management accounting encompasses the first section of this research paper. The second section investigates costing as a critical component of management accounting. The third (and last) section investigates costing concepts such as activity based costing (ABC), activity based management (ABM) and how they aid managers makes better managerial decisions for optimum organizational performance. Comprehensively, this paper demonstrates that management accounting is an important tool in decision making, based on the premise that it not only organizes organizational data but shows how businesses can be profitable and efficient.

History and Evolution of Management Accounting

Many people have often perceived research into the history of management accounting as unimportant because it has minimal scientific basis and contributes little to the process of developing current practical (accounting) problems (Chadwick 1998). From the development of these debates, the quality and sophistication of studies investigating the history and development of management accounting have significantly improved.

Two perspectives prevail in the understanding of the history of management accounting. The first perspective is the economic rationalist view and the second perspective is the Foucaldian view (UNISA 2011). The economic rationalists view centers on the perception that accounting is a mere technological response to the changing needs of the business environment (UNISA 2011). For example, the industrial revolution brought a new wave of economic changes to the business environment and in this regard, the accounting techniques developed at the time were a response to these changes in the business environment. The faucoldian understanding of management accounting was an effort to understand modern management accounting. This movement followed the economic rationalist view (UNISA 2011).

The entrenchment of the faucoldian approach therefore implies that the history of management accounting has been influenced by new developments, advances and insights of modern accounting. The Faucoldian understanding of management accounting shows focuses a lot on the 18th century period (thereabout) because of the monumental economic changes that occurred at the time (UNISA 2011). Proponents of the faucoldian view often believe that the history of management accounting can be linked to a social theory because its understanding can be best understood from the social, political and economic conditions of the time (Chadwick 1998).

Despite the apparent differences between the faucolian view of management accounting and the economic rationalist view of the same, it is important to point out that both views are significant to the understanding of management accounting. The economic rationalist view is especially important to understand the developments that have occurred in managerial accounting throughout the decades while the foucaldian view is best used to understand how management accounting developed to be a profession.

Before we take a deeper insight of managerial accounting, it is equally important to point out the differences between cost accounting and managerial accounting because both terms have been used synonymously. UNISA (2011) explains that “Cost Accounting is concerned with cost accumulation from inventory valuation, whereas management accounting relates to the provision of appropriate information for decision making, planning, control and performance evaluation” (p. 3). UNISA (2011) also explains that the history of management accounting is very short and exciting by explaining that “while management accounting concepts can be traced back at least to the beginning of the industrial revolution, management accounting as a discipline seems to have got off the ground in the late 1940s” (p. 4).

Nonetheless, UNISA (2011) explains that, the history of management accounting can be placed in two historical contexts. The first historical context denotes the first managerial accounting revolution while the second historical context is denoted by the second managerial revolution. These eras define periods where major strategic changes occurred in the discipline of managerial accounting.

The First Managerial Accounting Revolution

The first managerial accounting revolution is divided into two parts: 1700s -1800s and 1950s -1980s

1700s – 1950s

The history of management accounting before the 1950s period is often termed the ‘classical’ period. UNISA (2011) points out that the contributions to the field of management accounting during this period were particularly unfruitful because throughout the 1820-1885 periods, financial information was merely being recorded. The emergence of hierarchical organizations through the industrial revolution (such as the emergence of milling industries and rail-road companies) however brought an end to this accounting practice and heralded a new era of critical financial recording. Particularly, the emergence of these companies created a new demand for accounting information.

The economic revolution brought about by the industrial revolution (between the 18th and 19th century) posed new challenges for accountants (Chadwick 1998). The complexity arose from the increased sophistication of business operations and consequently, there emerged a new need to complement new business processes. From the proliferation of manufacturing processes, accountants were required to provide the right financial information to control expenses and price products accordingly (Khan 2006).

The term – management accounting was not commonly used in the Anglo-Saxon world (before the first management accounting revolution) because cost accounting was used in its place to refer to processes of cost computation and financial control (Maskell 1991). UNISA (2011) points out that even though there was no particular recognition of management accounting before the 19th century, there is a strong possibility that businessmen were already using the concept, unknowingly. In a recent address made at the Chartered Institute of Management Accounting (CIMA), it was confirmed that several management accounting practices existed before the 19th century (UNISA 2011).

These management accounting practices were mainly practiced in the textile, iron and extractive industries (Johnson and Kaplan 1991). For instance, in most farming industries, calculations were characteristic of a farm’s decision-making processes. Historical evidence in the works of a French mathematician named Agustin Cournot also provided evidence of the application of management accounting principles because he often said that a monopolist would stop production once the expenses exceeded the receipts (UNISA 2011). It is therefore clear that management accounting was a technical precondition for the pursuance of organizational objectives. However accounting organizations that existed at the time focused more on cost accounting as opposed to managerial accounting.

In North America, the first organizations to adopt management accounting were found in the textile or cotton-manufacturing industries (Johnson and Kaplan 1991). The application of management accounting was evidenced in the ascertainment of overhead costs and direct labor costs. This was mainly done during the conversion of yarn into fabric. An electrical engineer named Emile Garcke and an accountant named John Manger Fells were the first professionals to document the principles of management accounting (around 1887) (UNISA 2011). These pioneers were also later accredited to be the founders of the principles of marginal costing.

In a paper titled On the relation of cost to value, another accounting pioneer named Friedrich von Wieser also added to the growing proliferation of cost accounting principles by coming up with the concept of ‘opportunity cost’ (UNISA 2011). Many evidences of manufacturing cost records were later unveiled by historians but among the oldest records were sourced from the books of Boston manufacturing company. These records dated back to early 1815 and they showed sophisticated sets of accounts which were used in decision-making (Johnson and Kaplan 1991).

1950s -1980s

Epstein and Lee (cited in UNISA 2011) demonstrate that the first elements of management accounting as we know them today first gained prominence in the 1950s. This move heralded the birth of modern management accounting as we know it today but it slowly faded off towards the start of the 1980s period. It is also believed that this period kicked off a desire for new tools of research which also meant that managers were better equipped with new accounting tools for better decision-making (Hansen and Mowen 2006). According to UNISA (2011), most of the accounting management tools developed during this period was reflective of the economic theory.

UNISA (2011) further points out that different assumptions such as: tasks are made to be routine at the management and the operational levels, the external business environment is relatively stable (with few demand and price fluctuations), the sole purpose of management accounting is to aid decision-making, characterized the research that occurred during this period.

Principles of management accounting were first formalized during the first management accounting revolution where several leading higher education institutions such as Harvard and MIT integrated the discipline into the curriculum of master in business administration (MBA) (Hansen and Mowen 2006). This development occurred after the Second World War. In addition during, this period, management accounting was no longer only perceived as a tool for decision-making but also as a tool to aid in traditional business problems like how to improve profitability and efficiency in the organization.

Developments in the field of economics and decision theory were attributed to be the leading causes of the change in perception of management accounting (Hansen and Mowen 2006). However, the biggest flaw of these external forces was the failure to include environmental changes (like changes in technology, competition or even product demand) to the decision-making process. From this realization, UNISA (2011) stated that the new decision-making tools of management accounting assumed an unlimited rationality data, thereby making their outcomes to be less beneficial compared to the initial costs used to develop them

The Second Management Accounting Revolution (1980-1999)

When mathematical modeling techniques were used in the development of management accounting, there came a sharp division between educators and researchers of management accounting (Hansen and Mowen 2006). By the start of the 80s, there was a wide consensus among educators and researchers that the current curriculum used to teach management accounting was no longer relevant to the existing business environment (Bhimani and Bromwich 2009).

From these concerns, notable researchers in accounting such as Kaplan and Johnson recommended a raft of recommendations such as extending management accounting into non-financial areas, understanding contemporary problems and the information needs of managers, plus introducing innovative practices in management accounting as possible strategies to improve the usability of management accounting techniques (Johnson and Kaplan 1991). These developments heralded the introduction of the post-modernism period of management accounting (1980-1990) (Johnson and Kaplan 1991).

The main characteristic of the post-modernism period was the abolishment of a mechanistic view of accounting to the acknowledgement that accounting was operating within a set of organizational interdependencies. UNISA (2011) categories the main changes that occurred in the post-modernism period within two categories comprised of measurement issues and control issues.

These developments were also characterized by the realization that production processes had undergone immense changes over the years but management accounting procedures did not reflect such changes. According to two researchers, Epistein and Lee (cited in UNISA 2011), the acknowledgement of these changes required a modification of management accounting practices to reflect new costing models (to accommodate changes in production processes), and the recognition that investments in new accounting practices need to be cost-effective.

The above developments were also made with the recognition that most accounting researchers were not reflective of the challenges that accounting practitioners faced. These developments also acknowledged the extent that accounting practitioners were out of touch with their organizations. Through these disconnects, it was important for management accounting to be supportive to the quest to realize organizational goals. The balance scorecard technique was hereby perceived to be very useful in the development of measurement and control problems (Johnson and Kaplan 1991).

Seeking to respond to the challenges of management accountants, most management accounting literatures became more management-oriented. These developments greatly characterized the second management accounting revolution. Some management accounting literatures proposed the changing of organizational structures to reflect the modern business environment while others supported the changing of the concept of cost accounting to cost management. Concisely, the second management accounting revolution empowered management accountants to better measure newer and more complex accounting situations which were characteristic of the modern business environment (Johnson and Kaplan 1991). This development had a profound impact on accounting practice and accounting research.

Comprehensively, based on the history of management accounting, it is clearer now that changes in the business environment will continue to shape the way management accounting is practiced. For example, the year 1999 clearly shows a period when management accountants had to change their practices to be cognizant of the need for better decision-making in organizations (UNISA 2011).

How the History of Management Accounting is Relevant in Today’s Business Environment

Based on the above analysis of the history of management accounting, it is crucial to highlight how the history of management accounting is relevant to today’s business environment. The relevance of management accounting to today’s business environment is shrouded in controversy regarding the relevance of management accounting in the first place (considering the fast-paced technological environment) (Kamal 2011). Some researchers have often argued that management accounting has not changed much from the early 20th century and therefore, it is of little relevance to the 21st century business environment (Kamal 2011).

Based on this criticism, it is seen that there are many management accounting techniques which have been invented in recent decades thereby limiting the effectiveness of management accounting to influence managerial decisions.

Kamal (2011) proposes that recent additions to management accounting, like activity based techniques and strategic management accounting have developed across a range of industries and they now redefine the way management accounting influences managerial decisions. The new technologies have been developed to complement modern accounting practices and prop up modern technologies in management practices (Kamal 2011). For example, the introduction of total quality management (TQM) and just-in-time (JIT) accounting procedures have been borne from these new accounting practices. These accounting procedures have been invented in recent times to improve organizational competitive advantage in the wake of global competition.

Introduction to Costing

From the above literature, we can see that accounting has tried to encompass changing market dynamics and address the needs of present-day managers. However, through the incorporation of costing into mainstream accounting practices, there has been a rich history describing how costing became a mainstream accounting procedure. Costing was part of a three-faced accounting process which was also characterized by financial accounting and capital accounting (as the other pillars of the three-faced accounting system) (Kucera 2012). Financial accounting focused on the daily issues relating an organization’s financial performance but it also focused on important matters of profitability (as well).

For instance, railroad companies started to come up with operating ratios as early as the 1850s, thereby providing the right framework for analyzing a business’s profitability or loss (Kucera 2012). As the name suggests, capital accounting mainly focused on understanding the value of an organization’s goods. This development was particularly useful to rail road companies which experienced immense challenges trying to quantify the value of the huge capital invested in the business (through repairs or renewed investments) (Finkler and Ward 2007).

Costing as we know it today developed from the innovations made in financial accounting and capital accounting. Indeed, costing developed from the ascertainment of costs between different departments or divisions within an organization (Finkler and Ward 2007). Through this development, costing was able to accommodate the divergent needs of companies which had different departments. The needs of multi-divisional companies were effectively accommodated towards the end of the 19th century.

However, during this period, there were serious overlaps between elements of financial accounting, capital accounting and cost accounting. In this regard, Kucera (2012) explains that, “For example, to accurately determine unit costs, it was necessary to relate overhead costs and capital depreciation to the volume of production. At the same time, unit costs were typically used to determine prices, which in turn affected financial accounts” (p. 4).

Early evidences of the use of costing were documented in the use of cost accounting techniques by the Louisville & Nashville Railroad in the 1860s (Finkler and Ward 2007). Kucera (2012) explains that “This enabled the company to determine such measures as comparative cost per ton-mile among its branches, and it was by these measures, rather than earnings or net income, that the company evaluated the performance of its managers” (p. 3). Upon the evolution of accounting practices by the late 19th century, costing was no longer a preserve of rail road companies because it spread to other large companies across the world as well.

The major turning point in the application of cost accounting is its usefulness to organizations. At the center of this observation are the roles of management accounting in cost control and the improvement of organizational efficiency (Finkler and Ward 2007). The introduction of cost control as a critical component of accounting birthed the concept of costing. Conjecture Corporation (2003) explains that costing systems are just part of a wider synchrony of organizational systems. As implied in earlier sections of this paper a costing system is mainly intended to ensure that company costs are maintained at a favorable level to a business. While data used in costing systems can be easily integrated into other organizational systems, it is normally used to provide accurate information for decision making (Finkler and Ward 2007). Therefore, an organization’s upper management is the main user of costing information.

Usually, the information present in costing systems is used by managers to determine the status of operational expenses and all the expenses that are related to the general operations of a business (Kinney and Raiborn 2008). This usefulness of costing information encompasses the first base of costing in the decision-making processes. Usually, these expenses are skewed to encompass production expenses. The second aspect of organizational operations that costing helps to improve in the decision-making process is the ascertainment of performance costs.

Through the ascertainment of performance costs, managers are able to examine all organizational expenses that have a direct or indirect impact on the company’s profitability (Conjecture Corporation 2003). Profitability is usually determined after considering all direct expenses of production. A performance cost module normally encompasses different organizational expenses such as marketing and public relations costs.

Through the above understanding of costing systems, it should be understood that costing systems are not intended to replace existing accounting systems. Instead, costing systems are part of accounting systems, although they are unique to the fact that they focus on extracting information for easy analysis (Kinney and Raiborn 2008). For example, if a manager wants to quickly identify expenses that have been beneficial to the company, he would easily analyze the costing reports.

The efficiency in analyzing the critical aspects of the company’s performance improves a manager’s efficiency because it equally improves their efficiency in utilizing company resources (Kinney and Raiborn 2008). Comprehensively, we can easily see that costing minimizes waste and inefficiencies in the organization. Regarding efficiency, costing facilitates the direction of company resources to more productive areas of operations as opposed to using company resources for operations that have a poor or low yield (Kinney and Raiborn 2008).

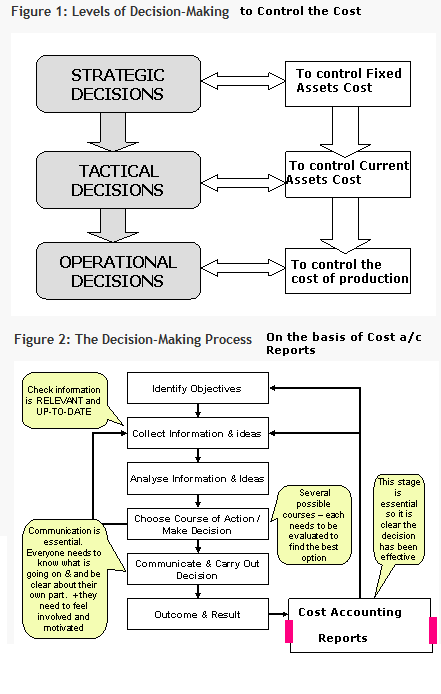

Practically, costing has been used to understand the value of inputs and outputs “by tracking and categorizing this information according to a rigorous accounting system, corporate management can determine with a high degree of accuracy the cost per unit of production and other key performance indicators” (Conjecture Corporation 2003, p. 3). The usefulness of such information is invaluable to management because they need it to make critical decisions about an organization’s performance, including production decisions, competitive strategy decisions, investment decisions, and several other tenets of management. The diagram below shows the relationship between costing procedures in the development of strategic decisions, tactical decisions, and operational decisions.

In detail, we can see that costing helps in controlling fixed assets costs, current asset costs and the overall cost of production. Furthermore, from the diagram above, we can also see how cost accounting reports aid in the decision-making process by collecting information and ideas, analyzing these pieces of information and ideas, choosing the right course of action and finally, communicating and carrying out the decision. These pieces of information are ordinarily important for internal company operations, although their importance is also appreciated in management accounting circles.

Overview of Current Costing methods

As mentioned in earlier sections of this paper, accounting practices have been keeping up with the changes in the business environment. Because of these developments, different accounting practices have developed newer tools that effectively meet the needs of management. Some of the most important developments in the accounting filed have happened within costing systems (Kinney and Raiborn 2008). Therefore, some of the most celebrated costing methods we know today have developed from their adaptability to the changing business environment (and the sophistication of business processes). An overview of the current costing methods reveals that process and job-order costing, activity based management and activity based costing are some of the major costing methods practiced today.

Process and Job-order Costing

Process costing is the most conventional costing method used in manufacturing. This accounting method has been traditionally associated with mass production of goods and services such as the bottling industry (which fills millions of bottles with soda every day) (Conjecture Corporation 2003, p. 3). If we were to analyze the application of activity based costing on a bottling company (like the one mentioned above)

“Activity-based costs might include operating the dispensing machines, performing quality checks, moving pallets of bottles, and so forth. Each of these activities may involve human labor, equipment costs, energy and expendable resources, and materials, but for analytic purposes the costs are all lumped together under a single activity concept” (Perkins 2002, p. 12).

By contrast, the job-ordering costing method is very detailed because it factors all costs associated with a production process. This costing method is particularly preferred when a company engages in the production of only a few goods (such as the production of ships) or when the production processes are very dissimilar (Sheeba 2011, p. 67). In job order costing, the production costs are not associated with the production of other products. They are calculated individually (Sheeba 2011, p. 67). However, job-order costing is not only used in manufacturing because other industrial processes also incorporate the costing method in their operations. In spite of the differences between process costing and job-order costing, a business may decide to use job order costing and process costing in their operations (at the same time).

Activity Based Costing (ABC)

Activity based costing is considered to be a complementary (or supplementary costing method) because of the contribution of the two previously discussed costing methods. Traditional costing methods normally classify costs into direct costs, labor costs and other generic costs but activity based costing normally classifies all the costs associated with one product (regardless of whether they are labor costs, material costs, or any other cost) (Bradtke 2007).

The advantage of this costing technique (ABC) is that it can provide management with a better insight into which tasks are the most expensive and which ones add more value. Such an analysis may expose areas where disproportionate amounts of money are being spent and which tasks are being underfunded or run at relatively expensive costs (Bradtke 2007). Such realizations may prompt the management to outsource certain services to third parties who may undertake them cheaply. Sometimes, this method can be referred to as “activity-based cost management (ABCM) or simply activity-based management (ABM)” (Perkins 2002, p. 12).

Activity Based Management (ABM)

Another accounting technique that has gained prominence among most organizations today is the activity based management technique. This costing technique is misunderstood by many to be a replacement of cost of sales and inventory evaluation but this is not the case (SaferPak Ltd 2006). In fact, in the valuation of cost systems (in financial books), there is no direct reference to activity based management (SaferPak Ltd 2006).

However, even as we understand how different costing techniques help managers in decision-making, we need to comprehend the fact that activity based management is more of a managerial process as opposed to a technique. The implementation of the ABM process needs to be embraced by all levels of employees in the organization for its comprehensive advantages to be truly realized. ABM was initially not such a popular concept in management but recently, it has come of age and is now being used in different economic sectors such as manufacturing, service sectors, utility sectors and similar economic sectors (SaferPak Ltd 2006).

SaferPak Ltd (2006) explains that with the adoption of ABM, businesses can better manage and make decisions regarding their product and service costs ,but more importantly, they can make crucial decisions regarding customer profitability. SaferPak Ltd (2006) further notes that by itself, ABM plays a critical role in change management processes in the organization. This is the very basis which it helps managers make better and more informed decisions regarding their companies’ operations.

The contribution of ABM processes on change management initiatives do not however encompass all the areas that this managerial, technique aids in decision-making; there are other business processes such as “profit improvement initiatives such as Business Process Reengineering, Shareholder Value Added and Customer Relationship Management” (SaferPak Ltd 2006, p. 3) that potentially use ABM concepts.

Among the greatest misunderstandings about ABM is what it potentially offers to managers to make them better decision-makers. SaferPak Ltd (2006) professes that ABM concepts mainly help managers better understand product and customer profitability so that they can be improved for the benefit of the organization and the customers as well. In addition, ABM concepts also help managers understand the cost of business processes so managers can make informed decisions about the company’s business processes. Traditional accounting techniques (such as standard costing techniques) are however shy of providing such information and it is therefore surprising that many organizations have not embraced ABM yet (Banjerjee 2005).

Many management techniques have been used in different organizational contexts to the benefit or frustration of the organizations concerned. However, 80% of companies which adopt ABM techniques in the managerial processes are reported to find the concept very beneficial (Banjerjee 2005). The main basis for this success is the fact that many organizational activities use resources (such as human resources, materials, equipment and the likes) and such resource utilization can be effectively measured by adopting ABM techniques.

Since most organizational processes are based on activities, knowing what these activities are, what they cost and what drives them is therefore a useful advantage in the decision-making process (Banjerjee 2005). Most importantly, knowing how different components of organizational activities are linked together helps to provide a more comprehensive oversight of how an organization works.

Manufacturing activities provide an example of one type of organizational activity that has been studied for decades. Cost drivers such as materials, and labor are known to constitute some of the most notable overheads in manufacturing processes (Banjerjee 2005). However, what many people do not know is that these costs (materials and labor) only account for about 75% of all manufacturing costs (SaferPak Ltd 2006, p. 3).

The other 25% is known to be overhead costs which are normally unmeasured. The situation is reverse in the service industry because material and labor costs only account for about 25% of the overall costs while the larger 75% of costs are rarely measured (SaferPak Ltd 2006, p. 3). Traditional management information systems derive their weaknesses from the lack of analyzing these unmeasured costs. Conveniently, ABM fills this gap by measuring these neglected costs. SaferPak Ltd (2006) points out that analyzing a business merely on the basis of which activities drive up its costs is the framework for developing new knowledge. This new knowledge also forms the right framework for the realization of higher business profitability.

In a nutshell, ABM sheds some light on invisible costs and entices managers to act on these invisible aspects of a business’s operations for the improvement of organizational performance (Banjerjee 2005). Nonetheless, since ABM majorly focuses on numbers, it is ordinarily perceived to be a tenet of financial accounting. However, the main strength of ABM is providing accurate information for all business processes and organizational departments. Its financial nature does not limit the extent which it can benefit an organization.

Normally, regardless of the nature of business, managers in different organizations are normally hungry for information that can help them to know how the company can better position itself in the market (for which accurate product and customer profitability information is pertinent) and how the company can improve its internal capability and decrease its unit costs (where information regarding changes in procedures, systems and processes that result in product development need to be considered carefully) (SaferPak Ltd 2006, p. 3). Apart from these managerial needs, it is important to also point out that today’s organizations are also very complex in structure and therefore, integrating the ABM model in the business’s process requires careful structuring and negotiations.

Integrating the ABM model is however only the start; effectively integrating ABM in the managerial process is a way to give managers new insight into what factors drive organizational costs (however, managers are not always empowered to know what tools to use to control these cost drivers) (SaferPak Ltd 2006, p. 3). Nonetheless, the ABC model was first introduced as a way to establish product costs more accurately but with the emergence of activity based management (ABM), a new way of enhancing business profitability was introduced.

Future of Costing

The activity based costing movement which started in the late 80s has taken most corporations by storm because it has created rigorous cost accounting systems for most companies. However, the needs of most managers are encompassed within the analytical prowess of the ABC system, but many organizations still need the conventional abilities of traditional costing models such as job-order costing to manage their operations (Bradtke 2007).

The failure to include both conventional and new costing systems has prompted many organizations to abandon ABC systems since they can be expensive to implement in large organizations (Baker 1998). Some organizations still view ABC system with much suspicion because historically, there are some organizations which reported the costing model as an unfit substitute for conventional costing methods (Bradtke 2007). Other organizations which have embraced it perceive it to be an ‘either-or’ costing model. Based on the concerns expressed by many organizations, ABC has been largely used as a supplementary costing model because it cannot effectively replace traditional costing models (Bradtke 2007).

Proponents of ABC systems are looking for ways to better integrate it with traditional costing methods so that organizations can effectively benefit from the advantages of both costing models. In 1999, the leading organization for managerial accountants (institute of Management Accountants) revised the guideline for the implementation of ABC systems by highlighting the potential pitfalls for adopting such a costing model (Bradtke 2007). Currently, its guidelines are developed from the successes of ABC implementation (from previous years).

Going forward, there is a lot of attention currently given to a related practice – target costing, which has been garnering a lot of attention since the mid 90s (Clifton 2003). Target costing is mainly intended to engineer a product’s production process from the start so that it can effectively match with the intended costing model. Some observers perceive target costing to be an elaboration of the engineering costing approach (Clifton 2003). Target costing has also been proposed by some observers as a possible solution for the mismatch between production processes and their costing models because it aims to create optimally efficient processes from the start (Clifton 2003).

A profitable and marketable selling price is often established from the start so that the pitfalls of incurring product expenses and looking for ways to cut costs at the end are avoided. Observers often cite the fact that target costing techniques do not necessarily require the input of the accountants because product marketing managers and engineers also have a significant role to play in the implementation of the costing model (Clifton 2003). Several professional bodies such as IMA systems have embraced target costing and subsequently formulated guidelines for its overall implementation. Clifton (2003) believes that target costing is going to be the future costing model.

Analysis of Costing Concepts

From earlier sections of this study, we have seen that costing is an important component of accounting. From this importance, we can affirm that costing is important in the decision-making process because different managers rely on costing procedures to ascertain different values of their production processes. Managers are increasingly faced with the problem of making good decisions for their companies and in today’s world of many alternatives, this process is very difficult. However, prudent decision-makers are still expected to select the best alternative strategy among a sea of other viable strategies to determine their best courses of action.

The positive message for managers is that there are several cost accounting techniques that are within their disposal and which can be used in the decision-making process (Ilango 2009). Some of these details will be discussed critically in subsequent sections of this paper but an overview of the importance of costing procedures on managerial decision-making borders on its importance in controlling material costs, controlling labor costs, controlling overheads, measuring efficiency, budgeting, price determination, curtailment of loss during the off-season, expansion and arriving at prudent managerial decisions (Ilango 2009). These areas in the production process highlight important tenets of production and ultimately, the important components of management.

The business environment is often very unpredictable and is therefore marred by a lot of uncertainties. Managers are therefore faced with a lot of challenges regarding their business processes because operational costs and market dynamics greatly influence their overall profitability. It is through such uncertainties that managers rely on costing models to determine the actual cost of processes or departments so that they can stabilize their budgets (Ilango 2009). The costing models therefore allow the managers to correctly analyze the fluctuations in budgets and operational costs and how company resources are used socially for profit.

Here, it is important to highlight the fact that cost accounting is still an important component of managerial accounting because cost accounting models inform a manager’s decision to cut costs for the overall improvement of a company’s profitability. There is a sharp contrast in the way cost accounting is used as an internal management tool because it is usually more pragmatic, thereby distinguishing it from accounting tools that are preferred by external users (Ilango 2009). Through this understanding, like financial accounting, cost accounting does not need to necessarily follow the guidelines laid down by the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) (Ilango 2009).

Among the greatest hallmarks of cost accounting is its ability to create value from production processes. It does so through the conversion of currencies into measurable units, thereby making it easier for managers to find the relation between production and actual sales. Ilango (2009) affirms that

“By taking recorded historic costs a bit further, cost accounting allocates a company’s fixed costs over a specific time period to what items are actually produced during that period of time, creating a total cost of product production. Products that were not sold during that period of time produced a full cost of those products, recording them in a complex inventory system that uses accounting methods of its own that are in compliance with the GAAP standards” (p. 2).

Through the above process, managers are able to concentrate on every period of production, bearing in mind the standard cost of producing every product in their different product manufacturing segments. There may be cost distortions in the above example if the overheads of producing a product are calculated viz-a-viz what the unit costs are (of producing only one product) (Ilango 2009). However, these cost distortions are often very minimal in organizations which manufacture goods in mass. Among the greatest additions of cost accounting to the managerial decision making process is its ability to effectively collect data which is thereafter used in the decision-making process. Different data collection tools are used in cost accounting. Some of them are discussed below.

Cost Sheet

The cost sheet is an important tool for business decision-making. Cost sheets are often produced from analyzing different costing procedures but their importance is best highlighted when trying to determine the right price for each unit of product produced (Allen 2009, p. 352). Cost sheets often contain information regarding a product’s price throughout different periods and therefore, a manager can compare different cost sheets to ascertain the right margin to increase or reduce the cost of the product. Managers can also easily identify which areas of production are taking up most of the company’s expenses, simply by looking at the cost sheet (Allen 2009, p. 352).

Usually, this process is done when the cost sheet shows a company’s costs increasingly escalating. Through a careful analysis of the cost sheet, a manager can identify areas of wastages and effectively reduce the same. Managers can also reduce the wastage by using quality product techniques to eliminate unnecessary production processes and by focusing on the limited production processes which add to the company’s value preposition. The standardization of raw materials can also be effectively achieved in this manner (Allen 2009, p. 352).

Labor Cost Reports

Labor cost reports are usually very effective in streamlining a company’s human resource inputs by ensuring there is no time wastages. Idle time is equally effectively reduced and staff turnover equally minimized (Ilango 2009). Labor cost reports are also very useful in making crucial management decisions regarding peak and off-peak seasons. For instance, the labor cost report is a useful tool to avert any losses that may arise from an off-peak season.

In such situations, the management may decide to adopt a flexible recruitment program where workers are temporarily laid off during off-season to avert any loss that may arise from paying idle workers (Ilango 2009). Alternatively, Ilango (2009) explains that workers can be diverted to busier departments of the organization during busy seasons, thereby averting the possibility of experiencing worker-overcrowding in unproductive organizational departments.

Overhead Utilization Reports

Overhead utilization reports are often very important during the allocation of resources to production processes (Ilango 2009). Sometimes, certain overhead costs are unjustified and some organizations run a loss by paying off such expenses. The overhead utilization report however empowers managers to pay only genuine overheads. Similarly, the payment of genuine overheads makes it easy for managers to distribute such costs on products, genuinely. Overhead utilization reports are therefore quite important in cost control because they calculate correctly the cost of overheads. Similarly, the overhead utilization report empowers managers to control organizational expenses which are not directly attributed to the production of the primary goods and services (Ilango 2009).

Cost Accounting Tools for Decision-Making

Marginal Costing

Some of the decision-making abilities of the above cited cost accounting techniques rely on the accuracy of the cost accounting tools used for decision-making. Marginal costing is one such technique which is used in decision-making. For example, in solving linear programming problems, linear variables have to be analyzed (like production costs and variable costs) (Ilango 2009).

The variable level and production costs are the most common variables in marginal costing but by acknowledging the relationship between production cost and variable costs, it is easy to determine an organization’s production level by simply maximizing its profitability or reducing the organization’s expenses (Finkler and Ward 2007). Indeed, through the marginal costing technique, it is easy for an organization to strike an equilibrium point of operation.

Cost Benefit Analysis or Breakeven Point Analysis

Closely related to the analysis of an organization’s equilibrium point of operation is the cost benefit analysis or breakeven point analysis. These techniques have been used by most managers around the world (mostly) to purchase fixed assets at reasonable cost. Most importantly, since the cost benefit analysis is crucial in purchase decisions, it is easy to point out the importance of this technique in helping managers make informed decision about expanding their businesses. Indeed, business expansions require the purchase of new equipment and machinery. Managers are therefore likely to find the cost benefit analysis and break-even costing tools to be important in the formulation of the right purchase decisions (Finkler and Ward 2007).

Nonetheless, these techniques are not only important for managers who are already in business; businessmen who want to start a new business may also find such costing techniques to be very important in their purchase decisions because it gives them an oversight of when they are going to recover their investments. The prudent production of goods and services has also been heavily reliant on cost benefit analysis and the break-even point analysis (Ilango 2009). Here, it is easy to determine the right level of production which amounts to the total revenue expected. The equality between the production level and the revenue realized is often perceived to be the break-even point (Ilango 2009). This is the production level desired by most businesses if they want to secure themselves from losses.

Activity Based Costing

Although activity based costing has been identified in earlier sections of this paper as a popular costing technique, it is also important to mention that it is a crucial tool used to prepare costing reports for managerial decision-making processes (Finkler and Ward 2007). As explained in earlier sections of this paper, activity based costing often assumes that activities are the main cost drivers for organizations, as opposed to the volumes of products produced within a given organizational department.

From this understanding, it is best to point out that managers who oversee the activities of companies which engage in different activities are likely to benefit from the advantages of activity based costing in the decision-making process (Accounting Coach 2012). Companies that also experience a wide variation of company tastes and preferences are also likely to benefit from the advantages of cost accounting in managerial decision-making.

The main logic of activity based costing is to allocate company resources across different organizational activities and therefore, managers who run companies that have minimal overhead costs and probably manufacture identical products are not going to find activity based costing to be highly beneficial (Accounting Coach 2012). However, it should not be mistaken that the overhead referred to in this case is manufacturing overheads only. Certain market dynamics such as customer demands are likely to affect other company overheads such as administrative overheads or selling overheads because of sophisticated demand. In such a case, the activity based costing technique would often demand that customers who are responsible for the high rise in overhead costs should be allocated such costs. Nonetheless, Accounting Coach (2012) cautions that

“If there is the diversity of products and customers (some require costly activities and some do not), it is not fair to simply spread all of the cost of all of the activities to all of the products and customers on the basis of just one activity, such as machining hours” (p. 11).

Referring to the above example, it is not fair to allocate company overheads which are not directly related to machine hours to the products and customers who do not necessarily use such activities. Only products and customers who demand these activities should be assigned the costs relating to such activities (Accounting Coach 2012). Managers who oversee the operations of companies which have very little diversity within their products and customers (or the company overheads are only related to a few company activities, such as, machine hours); the activity based costing technique is not likely to strongly complement their decision-making process. If machine hours is the main cost driving activity, it is only logical to allocate the company overheads using the machine hours as the main criteria.

However, if a company manufactures products that are not necessarily similar regarding the attention and activities that serve the customers, activity based costing is a good tool to complement the company’s decision-making process (Accounting Coach 2012). Comprehensively, the main contribution that activity based costing would provide such managers, is to identify efficient ways of production which can be used to base future company activities. The main objective for adopting ABC techniques is therefore to identify areas where there are production wastages and minimize them for optimum productivity. This process increases an organization’s return on investments.

Variance Analysis

The concept of variance analysis is very important in costing. Its importance hails from its ability to break down different variances into unique costs components such as standard costs and actual costs (Finkler and Ward 2007). Variances are often determined by the difference between expected and actual costs, although some literatures point out that variances are also caused by the difference between the budgeted, planned and standard costs (Sahai and Ageel 2000).

“These variations are often caused by several internal and external environmental factors but largely, they can be understood within the confines of material cost variations, variations of volume and labor costs variations” (Sahai and Ageel 2000, p. 4). These confines can be computed as costs or revenues. The differences between the planned and actual costs often have a compelling impact on the future of an organization and therefore, organizations are likely to be affected by such variations (Sahai and Ageel 2000).

Variations are however not similar in their nature and effect. There are some variations which have a strong impact on the organization while other variations have a minimal or no impact on some organizational activities. The effect and nature of these variations often determine the distinctions accorded to them. Specifically, when we analyze the effect of variations, we see that there are two types of variations (merely through the understanding of effects).

The first group of variations is determined when the eventual outcome is better than the expected outcome. Many scholars usually define these variations as favorable variances. These variances are also denoted by the abbreviation (F) but when the actual results are worse than the expected results, the variances that cause such outcomes are referred to as unfavorable variances (Sahai and Ageel 2000). This group of variances constitutes the second type of variance in this situation. These variances are often denoted by the letter (U) or the parentheses (A) (Sahai and Ageel 2000).

A second typology used to understand variances is according to their nature. Perhaps, the first typology used to categorize these variances is cost. Variable overhead production variances are also categorized into this group because of their close association with costs. Fixed production (overhead) variances and sales variances constitute the second and third typologies for understanding the nature of variances.

Managers find variance analysis to be a useful concept in decision-making because it bridges the gap between what the managers expect and what actually occurs. For example, managers may set the price of their products at a given level but market forces may erode their expectations, thereby resulting in unfavorable outcomes (Sahai and Ageel 2000). Variance analysis helps managers to avoid the pitfalls of such situations by helping them make informed decisions regarding future situations and how they can effectively manage such occurrences. There is no better way to understand the importance of variance analysis for managers than through budgeting. Indeed, variance analysis is an effective tool for budgetary control if not evaluating the performance of an organization.

Role of Management Accounting in Decision-making

Essentially, from the cost accounting techniques discussed above, we see that management accounting offers immense benefits to managers through different strategies. However, through the structures of these cost accounting tools, we can see that different management accounting concepts help to clarify important steps in the decision-making process, thereby simplifying the process altogether. One step that management accounting concepts help managers to overcome is the clarification of the decision problem

Clarification of the Decision Problem

Of all the benefits that management accounting concepts help managers, it is clear that management accounting concepts help identify the root cause of the problem by eliminating all distracters. Among the main disadvantages associated with the decision-making process is the fact that no decision has a guarantee of success. Therefore, managers only have to depend on probabilities by selecting the decision that has the highest probability of succeeding. However, it is not easy to do so if there are many distracters on the way. Management accounting helps to unearth the hidden problem rather than the apparent problem that most managers waste their time on. By identifying the right problem, it is easy for managers to effectively come up with the solutions to such organizational problems.

Merging Organizational Objectives with Organizational Activities

Different organizations have different goals and objectives. Depending on the stage of business lifecycle that an organization is in, managers are likely to have different organizational goals. Indeed, organizations that have existed for a long time are likely to be motivated by the goal of increasing profitability while businesses that are just starting up may be mainly preoccupied by increasing their market share (Sahai and Ageel 2000).

Cost accounting concepts help align such organizational goals with organizational problems by better highlighting the outcomes of different processes. For instance, if an organization is experiencing runway costs, it means that the likelihood of the organization being profitable is dismal. Therefore, through this revelation, an organization may decide to reduce its overall costs to improve its profitability. Somewhat, management accounting concepts help establish the right criteria for decision-making so that organizational managers know what to do with organizational processes so that they achieve their organizations’ objectives.

Exploration of Alternatives

By the very nature of management accounting processes and concepts, managers are able to evaluate their alternatives in decision-making. For instance, this paper highlights the cost-benefit analysis and activity based costing as possible techniques used in costing. Concisely, from the evidence given in earlier sections of this paper, both costing techniques use different techniques to achieve desirable objectives. The ABC technique bases its calculations from organizational activities while the cost benefit analysis tries to strike the best balance between different costs and benefits associated with different organizational processes (Accounting Coach 2012). Already, the focus on organizational activities and cost benefits provides an alternative for managers to choose which assessment criterion suits their organization.

Development of the Right Decision Model

The development of a right decision model primarily centers on eliminating all irrelevant information and focusing on what is important. This is the primary basis where management accounting techniques help managers develop the right decision model because they help eliminate all irrelevant information from the decision-making process and refocuses their attention to what truly matters (Accounting Coach 2012). For example, if we were to analyze the concept of costs, management accounting techniques would propose that only the costs that affect the future and those costs that differ among alternatives are the ones to be considered during the decision-making process.

Normally, in most decision-making dilemmas, differential costs, incremental (marginal costs) and opportunity costs would be the most relevant costs to consider during the decision-making process (Weygandt and Kimmel 2009). The differential cost normally refers to the difference in cost items between two or more decision models/projects or situations. In situations where the same costs or same amounts are witnessed in two or more alternatives, the differential cost becomes irrelevant to the managers (Accounting Coach 2012).

For instance, when a developer considers setting up an amusement park or apartment blocks on a piece of land, the piece of land is irrelevant in both cases because it would be used regardless of whether the developer decides to build an amusement park or set up apartment blocks. In the same regard, future costs and benefits that are witnessed across different decision alternatives become utterly irrelevant to managers.

However, a true example of the relevance of differential costs in managerial decision-making would apply in a situation where a company engages a market by using different distributors. If the company pays the distributing agent a commission of 15 million, any alternative decision where the company would pay less for the same service would be considered relevant. For example, if the company decides to engage sales agents as opposed to using distributors, the alternative would be ‘material’ for managers. If the alternative to appoint a sales agent costs 12 million, the differential cost would be (15 – 12) million to equal 3 million.

Obviously, this alternative would be cheaper and most companies would consider it but still, the risks associated with changing this alternative would have to be considered (Weygandt and Kimmel 2009). If the risk is high, it is probably a bad alternative to change the company’s market strategy from distributors to sales but if the risk is low, it is a viable alternative to change strategy. Ideally, in the decision-making process, differential costs should be compared with the differential revenues so that a comprehensive understanding of the existing situation is conceptualized.

For instance, in the above example, if the differential cost is 3 million, and the net worth to be realized from the change in strategy is 6 million; both values need to be considered in the decision-making process (Weygandt and Kimmel 2009). The consideration of both values will provide a better understanding of the decision to change the company’s marketing strategy.

Incremental and marginal costs do not behave any different from the differential costs discussed above (Accounting Coach 2012). Whereas managers look at differential costs as the cost associated with pursuing two alternatives, marginal or incremental costs are often perceived to be the costs associated with producing additional units (Accounting Coach 2012). For example, if we were to use the concept of marginal cost in an institutional setting, the cost of admitting more students would amount to the incremental cost. In a manufacturing company, the cost of running an additional shift would amount to the incremental costs.

For managers to arrive at the best decision (regarding whether to run a second shift not), like the differential costs discussed above, managers have to compare incremental costs with incremental revenues (Accounting Coach 2012).

Finally, another relevant cost which is highlight by costing techniques and which is of high value to managers is the opportunity cost. Opportunity costs are a critical component of most managerial dilemmas because managers are often faced with different alternatives that present different opportunities for the organization. These opportunities present different opportunity costs. Ideally, opportunity costs present the cost of forgoing a specific alternative.

For example, if Mr. Brown leaves his banking job which pays him about 500 pounds (monthly) and gains admission into a local university where he pays a monthly fee of about 100 pounds every month, his opportunity cost would be 400 pounds. If we were to analyze a second example where a fresh university graduate who gets two offers – one, in an investment bank which pays 1000 pounds and another, as a teaching assistant in a local university with monthly remunerations of 900 pounds, she would have something to lose if we were to compare her situation with a fellow student who only gets the teaching job and is happy to take it (Accounting Coach 2012).

These examples show that whenever an organization or person intends to undertake a specific project, it (or they) should not ignore the existing alternatives because these alternatives may similarly present opportunities for organizational success (Accounting Coach 2012). Ideally, an organization should evaluate all existing alternatives and decide which alternative is the best. Basically, this is the main characteristic for most managerial decisions but opportunity costs make it simple for managers to overcome such dilemmas (Accounting Coach 2012).

Perhaps the biggest deterrent for managers in choosing the right courses of action is the mix up between relevant and irrelevant costs. The presence of irrelevant costs greatly shrouds the process of decision-making because it hinders the effective conceptualization of the ‘real’ decision dilemma. However, cost accounting concepts help managers sieve through the volumes of irrelevant information by pointing out the necessary areas of managerial consideration.

Some notable irrelevant costs are like sunken costs (Accounting Coach 2012). These costs are past costs or historical costs and they cannot be changed with any future consideration. For instance, if a piece of land is purchased in London by a construction company for 30 million pounds and the company intends to erect a perimeter wall for another 2 million pounds, the initial 30 million would constitute the operation’s sunken costs but the extra 2 million pounds to erect the perimeter wall would constitute future costs (or out-of-pocket) expenses. The decision to erect the perimeter wall is definitely relevant to managers.

Similarly, if the managers decide to erect a three meter wall (or four meter wall) is similarly relevant in the decision making process. However, the cost of purchasing the land still remains the same at 30 million pounds and therefore, it is a sunk cost. Nonetheless, there are certain situations where a company’s managers need to make special decisions depending on the nature of the relevant costs or benefits. For example, a company’s managers may decide to accept or reject an order when there is excess capacity or they may also decide to accept or reject an order when there is no excess capacity (Accounting Coach 2012).

There are also certain situations where a company’s managers may decide to outsource the company’s activities or when they may be required to add or drop a company’s product. In the same fashion, a company’s managers may also deem it appropriate to drop an organization’s service or even department. In certain occasions, the managers may decide to sell or process an organization’s product further but in other occasions, he may decide to optimize limited resources because of production constraints.

Comprehensively, we can see that cost accounting techniques are very important for managerial decision making because they collect information from cost data bases and provides managers with the same information for decision-making. Many people often believe that such information only constitutes financial data but far from this, non-financial data is also relevant in this context. In fact, even non-numerical information is derived from these cost accounting techniques and used in the decision-making process. Accounting Coach (2012) explains that “While numerical information consist of operational statistics such as units produced, raw materials considered and labor hours used, the non-numerical or qualitative information pertain to customers satisfaction, employees moral, access to markets and image of an organization” (p. 5).

Therefore, for every decision made, there are different considerations factored and for all relevant decisions made (that have a bearing on the future), relevant costs must be calculated. If these qualifications are not met, the associated costs would be irrelevant. Since most decisions are made in a lot of uncertainty, costing techniques help managers make the best decisions by pointing out the best and worst situations of management (Debarshi 2011, p. 4).

Such guidelines can be seen from sensitivity analyses and simulations. Even though there has been a lot of progress made technologically, traditional costing techniques are still crucial to the decision-making process but more importantly, the introduction of the ABC, ABM and EVA techniques have made cost accounting techniques much stronger and more useful to managers (Accounting Coach 2012).

In other words, cost accounting techniques help produce simplified versions of managerial problems, thereby simplifying the entire decision-making process altogether. These cost accounting techniques not only help simplify the problem, they also help to bring together different elements to the problem such as the existing constraints, criteria and the alternative ideologies. When these factors are effectively exposed, managers have a better understanding of what they are dealing with but more importantly, they have a better conceptualization of all the relevant dynamics of the problem. This insight helps managers make better and more-informed choices (Debarshi 2011, p. 4).

Collecting Data

It is almost common knowledge that the best strategies are developed from the analysis of relevant data. It is therefore almost impossible to come up with the best strategies without collecting adequate data and more importantly, relevant data. There is no better tool that managers can use to gather the right information for making managerial decisions than through existing management accounting tools. Some of these tools include costing techniques and they have been highlighted in earlier sections of this study to show different dynamics of an organization’s operations. Indeed, different data is collected throughout an organization’s operations and they are later availed to the mangers for use at their discretion (Debarshi 2011, p. 4).

Some of the highlighted pieces of information noted in the sampled costing techniques are the operation costs, benefits accrued from existing operations, future breakeven point, which activities take up most costs, which activities bring the most revenue (and the likes). Management accountants are often the main custodians of such information and even though they mainly manage financial data, they also maintain records of physical units produced and any other tangible products used in the production process (Debarshi 2011, p. 4). Often, such information is also compounded with information about labor activity in the organization.

Such information also adds to the pool of data that cost accounting techniques help to accumulate. As if to mean that the pool of information already highlighted is not enough evidence of relevant information gathered by cost accounting techniques, management accountants are often tasked to provide information about employee morale, customers satisfaction and brand image as useful and additional information that are vital in the organizational decision-making process (Debarshi 2011, p. 4).

This information may be in form of primary or secondary data but the main focus should be on the relevancy of such information. For example, outdated information is not often tolerated in managerial accounting. Costing techniques only help to gather such information and avail them to the managers so that they can make better and informed choices. Accounting Coach (2012) elaborates that “A management accountant is a member of cross functional team and, having unrestricted access to MIS, makes a contribution by providing facts and figure which bring objectivity to the report” (p. 6).

To further explain the role of the management accountant in the decision-making process, Accounting Coach (2012) elaborates that “Besides, a management accountant would ensure that the information must be relevant (pertinent to the decision problem); accurate (precise); and timely (arrive in time for the decision to be made). Companies will occasionally trade-off accuracy for timeliness” (p. 7).

Management’s Role in the Decision-Making Process

Perhaps, the greatest hallmark for any potential manager is the ability to make the right decisions. Throughout most organizational structures, managers are often mandated to make executive decisions. The ability to make decisions is cited by Langley (1995) to be the greatest obligations of free people. In the same breadth, Langley (1995) points out that among the greatest characteristics of managers is to have the courage to make a decision.

Indeed, the most notable characteristic of our daily lives is decision-making. As noted in the above assertion, in the organizational structure, decision-making is the greatest underpinning of management. Concisely, many people often understand management and decision-making to be almost two concepts cut from the same cloth (Anderson 2012). This perception is created from the observation that managers make the most important decisions in the organization (Debarshi 2011, p. 4).

As will be seen in subsequent sections of this paper, decision-making involves the right selection of organizational strategies from a pool of other alternatives (Monahan 2000). However, arriving at the best option is not a walk in the park because managers have to judge the effectiveness of almost every alternative available. The process of evaluating every alternative requires the managers to be availed with relevant data and information pertaining to the same. For this reason, managers are often reliant on economic and financial forecasts. Most of such information is prepared by managerial accountants.

From the above explanation, it is open to our understanding that accountants play a critical role in the provision of accounting and economic information to managers. The importance of such managerial decisions should not be underplayed if the future of an organization is at stake. Langley (1995) points out that there is no shortfall of examples where managers have made poor decisions and driven their organizations to bankruptcy.

Langley (1995) even claims that “the road to bankruptcy is characterized by poor decisions” (p. 3). Since the road to making good decisions is often marred with many uncertainties, managers often fear to make the wrong decisions. Regardless of this fear, managers are still required to have the courage to make the most important decisions for their organizations (Anderson 2012). Indeed, good decisions are healthy for the long-term sustainability of an organization.

The role of managerial accounting in the decision-making process is emphasized in several definitions of accounting as explained by the statement that accounting as a profession is aimed at communicating and measuring important information to users (managers) so that they can make informed choices about their organizational processes. In addition, two researchers, Sundem and Stratton (cited in Langley 1995) perceive the role of managerial accounting in the decision-making process to be confined within the provision of detailed financial data for the formulation of prudent financial decisions. Therefore, the mere process of collecting and measuring financial information (through management accounting) can influence an organization’s decision making process (Anderson 2012).

Usually, these decisions are influenced to align with the existing organizational goals. Two researchers, Otley and Merchant (cited in Langley 1995) often perceive the main function of accounting information to instill some sense of control in an organization’s activities. Since managers often wield a lot of executive control over a company’s operations, it therefore comes as no surprise that accounting information is used to exercise executive control. This control is often witnessed in both strategic and operational activities (Anderson 2012). Therefore, it is flawed to differentiate the concepts of planning and control.

Nonetheless, the process of decision-making falls within the context of planning, control and the influence of organizational processes. From this understanding, it is simple to show how the decision-making process is part of an organization’s wheels of control. An accountant researcher named William J.B (cited in Langley 1995) explains that managers have the power to decide which information they want to include in their overall decision-making process. When the accounting information is considered to be more than the non-accounting information, it is only logical to say that the accounting information may have a stronger bearing on the overall decision-making process. However, the level of input regarding the accounting information may vary from one decision to another and from one manager to the other (Anderson 2012).

For example, different managers may have different goals, perceptions and experiences which may limit their use of accounting information (Monahan 2000). In addition, it is important to point out that when the accounting information provided has a strong bearing on the overall decision; it is more likely going to be considered. Usually, in such situations, the accounting information used is highly relevant. Furthermore, managers are also more likely to use accounting information if they have a high reliability and if there is inadequate financial accounting information available. Nonetheless, it is critical to point out that it is much simpler to use accounting information in the decision-making process because it is easier to grasp, describe and enumerate (Anderson 2012).

Tools for Decision-Making

Since managers need to keep tabs about an organization’s running costs, management accounting techniques play an important role in the decision-making process. Mainly, cost accounting techniques are used to determine the overall cost of goods produced in an organization. From this understanding, cost accounting techniques are considered among the most important tools for guiding managerial decisions (Monahan 2000). Indeed, without being provided enough information about operational costs, it is very difficult for an organization’s management to make informed investment decisions or set the right selling prices. This cost foundation is the main premise used by managers to adopt cost accounting techniques (Monahan 2000).

However, there are certain situations where managers prefer to use less rational tools of decision-making, although they may still be valid in the long-run. Langley (1995) explains these reasons as constituting “experience, intuition, moral conviction and the more trivial reasons in business politics – turf wars, power struggles, personal self-aggrandizement and the like” (p. 7). From this understanding, it is therefore important to point out that quantitative factors are not the only bases used to formulate important managerial decisions. Almost always, there is a situation where there are managerial decisions which are based on other factors apart from numbers.

Pricing and Competition