As the dreams for a global village get realised, challenges of diversity in the business place have become a common feature that can not be wished off as teams of totally different cultures, ethnicity and values work under the same management. These cultural diversities call for the need for corresponding diversified or hybrid management practices and structures that will accommodate everyone. Today, the success of any project that is built on a multi-cultural project setting is highly dependent on the way the issues on organisational culture are addressed and accommodated. Organisational culture, according to Deshpande and Webster (1989), can be defined as the practices that assist the workforce of an organisation to function together by guiding their thoughts and conduct. Previous researches have presented organisational culture as a complex interlink between norms and values within an organisation’s workforce that is generated over a period of time and impacts on the important organisational practices and actions (Barney, 1986). Therefore, organisational culture can be seen as a significant element and ingredient in implementing change in project management, for it is the “glue” that joins together the diverse cultural structures that can not be avoided in a globalised business environment (Pettigrew, 1990). According to Hofstede (1991), organisational culture can be likened to the computer software that works in our minds and should direct necessary changes to accommodate diverse values in the contemporary business environment that is extremely competitive.

There are four main categories of organisational culture that includes power, role, support and achievement culture that could trace origins from different societal setups around the world (McKenna, 2000). Any organisational culture that supports and adapts can be an important prerequisite for success in project management practices. In any organisation, there are a number of values that determine the effectiveness of project management practices. These values include the following:

Formalisation

In an organisation, formalisation represents the set of regulations, practices and documentation. These documentations define the behaviour of the workforce in the organisational and may include such documents as policy and job description booklets. Some scholars have criticised formalisation, citing that it could inhibit a free environment where creativity and innovation can thrive within an organisation. However, Zaman (2006) states that there has been no empirical evidence that has in particular supported this argument because high levels of innovative and creative management practices have continued to be evident in formal organisational settings. In addition, these kinds of formal regulations enhance organisational learning that eventually leads to effective communication, better problem-solving techniques and guides decision-making processes (Gold et al., 2001).

Trust

Fukuyama (1996) defines trust as the hope that emanates and develops within an organisation from one quarter to another, based on honesty and cooperation and driven by the shared norms and values. Trust between the professional sectors within an organisation is more important than person-to-person trust though efforts should be made to maintain both. Trust is a significant value in an organisation, and as Lopez et al. (2004) observe, it creates a secure atmosphere that is conducive for innovative risk taking practices that are aimed at experimenting on newly acquired knowledge and perfecting it.

Learning

Learning, according to Lee and Choi (2003), is the level of opportunities, varieties and efforts to encourage development within the workforce of an organisation. An organisational culture that values and encourages learning can be said to be more valuable than any form of technological innovation. This is because organisational learning builds the capacity for everyone to be innovative and also allows people to relate knowledge to organisational needs (Sinkula, 1994). Knowledge acquisition also helps in opening up ways for effective communication within an organisation (Bhatt, 2000).

Collaboration

Sonnenwald and Pierce (2000) define collaboration as the human action towards sharing in the completion and meaning of a given task driven by a mutual objective to enable the organisation to realise its mission and vision. Organisational collaboration creates an atmosphere where people can learn from one another and share responsibilities for important organisational tasks that call for collective responsibilities. Collaboration, therefore, is a useful tool for knowledge creation and innovation within an organisation that enhances the perfection of specialised tasks as it does not give room for a few individuals to be the only masters in their own field.

Organisational Structure

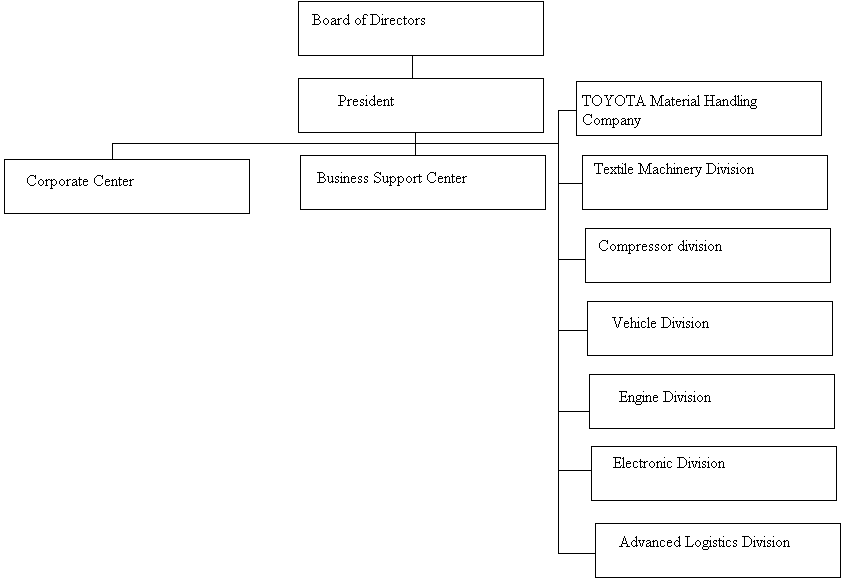

An organisational structure is an arrangement that helps in facilitating the way the project activities are coordinated and implemented (Fukuyama, 1996). The structure helps in creating an environment where the staff would work as a team with minimum conflicts, disruptions or overlaps. Due to the unique nature of every project, it is paramount for the management of an organisation to prudently study the environment within which the project is to be conducted and assess the amount of power bestowed upon the manager before deciding on the best structure (Gold et al., 2001). Once the best structure for the project is selected, the uncertainty and confusion that is common in the initial stages of a project can be avoided. The project manager is expected to ensure that the organisational structure developed defines the needs appropriately for the projects within all the stages of the project. An effective structure would clearly define the link between organisational management and the external environment as well as the authority levels in the form of a chart. For example, the operations for Toyota Company major decisions are ratified by a Board of directors who delegates the actual control of the company to the president. The president controls the various company divisions through respective managers, as shown in the flow chart below.

The chart, which is drawn in the form of a pyramid, shows where every member of the project is placed and shows the working relationship and the links of supervision within the organisation. The structure should, however, not be too rigid as to compromise its primary aim of fostering interaction between the staff but should enhance a formal environment through which the manager can be able to effectively influence the workforce towards achieving their organisational goals (Deshpande and Webster, 1989).

There are factors that influence the design of an organisational structure, and the main ones are the specialisation level and the necessity to coordinate. Specialisation has an impact on the organisational structure on the basis of the areas of speciality in technical fields. There are those projects that can be more specialised and focused on a certain area of development, while others have broader fields of development (Hoefstede, 1991).

Coordination is another important factor that should be put into consideration when designing an organisational structure, for it brings out the unity required for various project elements to work in unison. The project manager ensures that all the fields are integrated together so that each of them can play a part in generating the overall organisational goals. The need for integration is necessitated by the division of labour that is common in most organisations where every department carry out specialised tasks that need to work in harmony with others to achieve a common goal (Lee & Choi, 2003).

Types of Organisational Structures

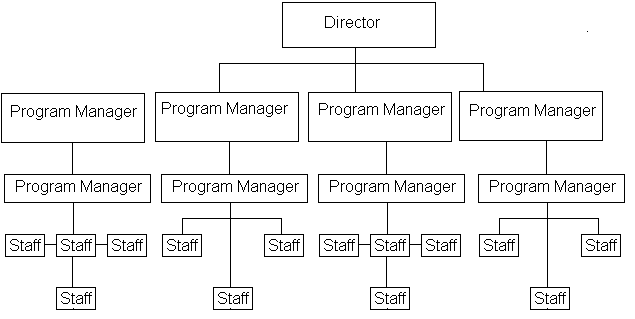

Programmatic-Based

This is a traditional structure where the project managers are given the power over the resources, and therefore, it is only suitable if the project is being carried out within a single project sector and not for projects where a diverse mix of partners may be a factor. In this structure, the staff normally constitutes people from one locality, and the resources are sourced from a single unit. This structure has an advantage in that the lines of authority are well defined, and negotiation for resources from different units does not arise since all resources are drawn from one unit. The structure is also composed of a workforce that knows each other and works in an environment free from cultural conflicts. The structure, however, has a disadvantage in that all specialists needed in the projects may not necessarily be available from one area. The following figure shows the organisational chart for programmatic based organisational structure.

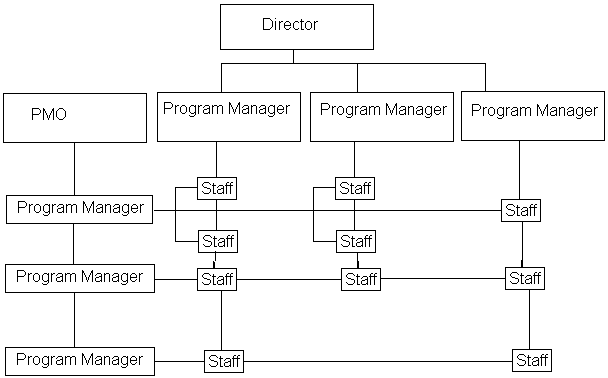

Matrix-Based

In the matrix structure, different program units are allowed to concentrate within areas of their expertise but can incorporate experts from other units. For instance, an electrical engineer may work at his unit be temporarily be sent out to other areas which may require electrical experts. The major advantage of this structure is based on its efficient way of utilising resources, especially the skilled personnel that is fully utilised across all the units where the services are needed. The structure is also very flexible in accommodating changes within a project and allows team members to share knowledge, a factor that enhances knowledge and professional skills development across the organisational units (Lopez et al., 2004). Matrix structures, however, have a disadvantage in that reporting and feedback relationships are complex, and the staff may end up reporting to the wrong managers who may take wrong to have the concerns executed. Working under many managers may also require a high level of time management skills to ensure that all targets are fulfilled as planned. The structure is also a challenge to some project managers that must consult with other project managers and programmatic managers to ensure that priorities are aligned to achieve a common goal.

Organisational structure chart for a matrix structure

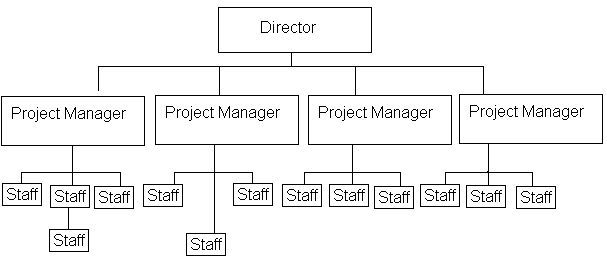

Project-Based

In project-based organisational structures, the project managers are entrusted with high powers of controlling the resources of the project and can acquire such resources either within or outside the parent organisation (Pettigrew, 1990). The projects lines accord the manager total control over the project affairs, therefore, significantly reducing the time feedback time for technical issues about the project. The staff under this structure are engaged on a full-time basis, thus, ensuring that they remain loyal to the project and gain a full understanding of their requirements towards achieving the project goals. This kind of structure is commonly used in large and complex projects that have a large capital base that can be able to sufficiently meet the cost to maintain a structure where resource and cost efficiency are not major priorities. The team members normally focus on one task at a time, and they lack time to share knowledge, a fact that limits professional development. One major disadvantage with this structure is that it gives room for duplication of resources because those resources that are scarce are allocated among different projects. Re-allocation of team members after successful completion of a project is also a challenge under this organisational structure. The resources used in this project may also not be required for the full length of the project, a fact that forces the project managers to engage in short consultation services that could be very expensive to the organisation (McKenna, 2000).

Project-based organisational structure

Organisational Culture Versus Organisational Structure

The entry of diverse cultural norms and values that each of the members of an organisation’s workforce brings into the workplace is, in normal circumstances, done unconsciously (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000). Though part of our cultural values may be demonstrated to others and one may explain what makes them happy or otherwise, yet most of what constitutes our culture are dictated mainly by hidden values that can easily catch up with us at the place of work. For instance, principles of interpersonal relations, approaches to people on authority, how we perform tasks, time consciousness, communication and learning patterns may be guided by instincts that are beyond one’s control (Sonnenwald & Pierce, 2000). Cultural values are transferred from one generation to another, and no one culture can be said to be right and another wrong. However, within different sets of culture, there are some elements of behaviour that is considered right or wrong. These cultural values influence the way in which people conduct themselves in the workplace and the kind of organisational structures that they are likely to create and adopt. Given the fact that the success of organisational goals is a function of time, such conflicts and underneath heat may be very expensive to the organisation. It is therefore very important to understand the organisational culture before deciding on the organisational structure to implement for such an organisation.

The following issues should be put into consideration when choosing an organisational structure for a project with a multi-cultural face.

Authority

Authority is a sensitive issue in any organisation, and given the fact that responsibility in a multi-cultural setup will be divided and delegated to people from different cultural backgrounds, then care must be taken to ensure that the structure does not use this factor as a point of conflict. Imposing a hierarchy that cannot be accepted by partnering parties can be disastrous to the project as it can cause low motivation of the workforce and slow down the project activities, which can be detrimental to the realisation of organisational goals. For instance, the south-European culture detests the flat hierarchies that are highly respected in Latin American culture. Having these two cultures represented within the same project means taking into account the feeling for each party and ensuring that both of them are at peace.

Time

When major partners for a project share different cultural backgrounds, then major conflicts in most of the project stages are expected, a fact that would certainly cause major time rags in the execution of the project. This time spent on reconciling one party to the other should be provided for in the planning stage. For instance, in Scandinavian and German cultures, project activities are scheduled in such a way that each takes its allocated time. This is a totally different approach from that taken by such cultures as France, where time is not considered as a commodity that can be put into a schedule that allows the activities to roll out on their own naturally. Therefore, different activities can be done simultaneously. In the Middle East, a project manager can divide attention between completely different activities, an act that really annoy a manager from Northern America or Northern Europe. The different perceptions in time can be a major cause of frustrations in project participation (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000).

Conflict

In general terms, projects have potential loopholes that can bring in conflicts between partners. Some of the common sources of conflicts are tight budget lines, activity time frames, goal setting or creation of project groups across project line functions. In a multi-cultural setting, it is more challenging to discover some hidden interests and hard-line stands that could be taken by some of the parties (Zaman, 2007). Conflicts can very easily emanate over the issues fueled by differences in cultural values, as behaviour patterns are usually rooted in these cultural systems. Even in cases where the parties are well aware of their differences, crossing the lines of intolerance in any of the parties may sow a seed of conflict that may later germinate to the full brown conflict that can jeopardise the project (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000).

Risk

Risk is an integral component in project management that can not be wished away, yet different cultures may have very different perceptions of the way risk should be handled in a project (Barney, 1986). In most cases, people prefer working in jobs that are secure, but unfortunately, projects are usually based on the temporary time frame, and the pressure on the workforce to perform and achieve the goals is very high. For instance, some cultures in Eastern Europe would not be very motivated to work in a high-risk project and would prefer having organisational structures that would significantly reduce the risk levels. There are other cultures that consider work related risk as a personal responsibility, in which case taking risk is only restricted within the levels of risks that can be computed based on the task at hand. The design of an organisational structure should consider such cultural views to ensure that the design is palatable to the parties represented in the project (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000).

Communication

Communication that can build healthy relationships is that which is generally harmonious in nature, but in some cases, communication used in projects focusing directly on tasks to be accomplished may be considered confrontational to some a larger extent (Sinkula, 1994). Appropriate use of communication to express an opinion in a given culture may completely be considered inappropriate in another culture because cultural norms are embedded in one’s language. Whenever there is a mismatch in communication mode, an unintended message may be sent and may cause frustration with the affected parties (Deshpande and Webster, 1989).

Organisation

The main function of a project manager and his team is to set flexible systems that would facilitate the achievement of the organisational goals and are greatly motivated when these goals and objectives are addressed. The activities of the organisation are therefore considered and treated as a more important component of the projects than the building of relationships among the workforce (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000). However, challenges emerge when people attempt to introduce task driven management styles in a culture that is mainly relationship-oriented, having been pushed by the need to have the activities scheduled for the project done and finished within limited time spans. For instance, the French culture, which is more relationship-oriented, would spark off conflict when its members work alongside Germans whose culture is more task oriented. However, it is important that an organisation commit to building a culture that is more adaptive where the workforce would be able to work together and be rewarded as a team. This approach is more encouraged in collectivist societies though people from cultures that encourage individual achievements may have problems in such a setup (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000).

Agreements and Contracts

The success of any project is based on mutual concessions signed among the major partners that define the roles, responsibilities and powers vested upon each one of them. The challenge in a multi-cultural setting is, however, the time that it takes to come up with a consensus on how these demarcations would be drawn as the perception on major issues that would direct such decisions are far much different. For some cultures, “gentleman’s agreement” is enough to strike a deal of great financial magnitude, while in others, a little deal must be clearly written and details emphasised and agreed before registered lawyers before it can be accepted for execution. The line of contention is usually on what each of the cultures would perceive as right or wrong, and in most cases, every individual believes that his perception is more logical than that of the partner (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000). Such differences may often result in mistrust and irritation that may not augur well with the progress of the project. The impact and consequences of these tugs-of-war may be devastating both to the individual and the parent organisation that may lose their reputation, identity or even money that may not be recoverable in case major mistakes are committed (Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000).

Conclusion

It is important to deal with cultural issues and challenges early at the start of the project and continuously review as the project progresses. This would ensure that the partners remain motivated and that financial gain for both partners and the parent organisation is realised. To facilitate the early evaluation of potential sources of conflicts, it is important for both the parent organisation and the parties to the project to develop a comprehensive understanding and appreciation of each others culture and identify risks and opportunities that can be exploited from the beginning of the project. The parties should jointly define the project’s goals and objectives and come up with a schedule through which these goals shall be realised. Identification of these important projects’ element helps in ensuring that the parties can define guidelines for the best organisational structure that takes into account their cultural differences. The parent organisation management and the project manager should work hand in hand to ensure that cultural awareness is brought up at the start-up of the project. The potential areas of conflict or disagreement should be identified and mechanisms put in place to coordinate information and track the progress in agreements that initiate mutual understanding among the participating parties. With such arrangement in place, the areas of conflict would be smoothly addressed, and the parent organisation will be able to initiate and nurture a favourable cultural environment that will aid the project activities, and the project managers will be well informed in their efforts to design structures that shall be most appropriate for their respective projects.

List of References

Barney, J. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11, 656-665.

Bhatt, G. (2000). Organizing knowledge in the knowledge development cycle. Journal of Knowledge Management, 4(1), 15-26.

Deshpande, R., & Webster, F., Jr, (1989). Organizational culture and marketing: defining the research agenda. Journal of Marketing, 53, 3-15.

Fukuyama, F. (1996). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: The Free Press.

Gold, A.H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185-214.

Hoefstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations. London: McGraw-Hill.

Lee, H. & Choi, B., (2003). Knowledge enablers, processes and organizational performance: An integrated view and empirical examination. Journal of Management Information Systems, 20(1), 179-228.

Lopez, S.P., Peon, J.M.M., Ordas, C.J.V. (2004). Managing knowledge: the link between culture and organizational learning. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(6), 93-104.

McKenna, E. (2000). Business psychology and organizational behavior. Hove: Psychology Press.

Pettigrew, A.M. (1990). On studying organizational culture. Administrative Science Quarterly, 570-581.

Sinkula, J.M. (1994). Market information processing and organizational learning. Journal of Marketing, 58, 46-55.

Sonnenwald, D.H., & Pierce, L. (2000). Information Behavior in dynamic group work contexts: Interwoven situational awareness, dense social networks and contested collaboration in command and control. Information Processing and Management, 36(3), 461-479.

Zaman S., (2007). Innovation and Organizational culture, Unpublished M. Phil Thesis, Quaid-I-Azam University, NIP, Islamabad, Pakistan.