Introduction

Even the most ordinary observer will realize that the present marketing environment has drastically gone through transformational changes in the recent years. The increased competition between companies both at the local and global arena has drastically changed the way things are done in the marketing scene. Companies have used many strategies such as mergers and acquisition, concentrated in building the image of their core business lines rather than dwelling on the initial non-essential lines of business. Some have adopted various techniques of marketing based on various aspects of corporate management strategies.

Basically, the nature of the retail environment continues to change with the simultaneous emergence of difference communication channels, emergence of specialized services, and competition among industry players that has brought about many brand choices for consumers to select from. The space of technological change is almost difficult to comprehend, with its double impact both on the nature of product and services consumers receive from companies, and how these customers are communicated to. Companies therefore have many channels in which they can reach their customers or target market, albeit at an increased cost.

Yet with all these numerous but confusing diversification of communication channels, marketing communication still present the single most important opportunity for companies to convince potential consumers of the superiority of their products and services (O’Grady & Lane 2006). Coffee companies have strived to approach the marketing of their coffee products and services in the industry that seen dynamic changes due to changes in lifestyle of the people.

Dr. Café, a Saudi Arabian coffee company has established itself as one of the top coffee sellers. Figuratively, the brand name, Dr. Café could be interpreted to mean a segmentation strategy to cut a market niche in the coffee industry. According to their business model, the company prides itself to delivery coffee products with high quality reinforced with good customer knowledge. They also “excel in extraordinary 1st place experience”1.

The company’s business model defines what they communicate to the customers (Dr. Café 2010). Popularly known as Dr. CAFÉ@ CAFÉ, the company is designed to continuously build a wonderful experience with its clients, whom they fondly refer to as ‘guests’ to foster the close touch with them. Some of these strategies Dr. Café has adopted are what entails their strategic marketing. In the integrated marketing communication, there is need to integrate all aspects of communication where the need to build a strategic goal is developed. Basically, strategic marketing communication, commonly abbreviated IMC can be viewed in two main perspectives.

The first perspective is based on an effort by a company to develop strategic communication with the target customers, and the second approach is for a company to focus on brand management. This report analyzes various components of IMC that Dr. Café has applied in as effort to establish and maintain progress with their customer initiatives. With the help of a marketing framework supported by competitors approach to integrated marketing communication behaviors, the report will identify the gaps that Dr. Café faces, and provide adequate recommendations necessary to enhance brand name and image.

Coffee Industry Statistics and Market Situation

The Saudi Arabian market analyses indicate that young people have increased the trend of spending a lot of time out of their homes, as they tend to socialize a lot. Coffee shops have become immensely popular given the fact other forms of entertainment are not available in the Kingdom. It must also be acknowledged that religious factors in the country and its entire region eliminates alcoholic drinks as forms of entertainment hence giving coffee shops good business opportunities particularly for expansion. Still, studies also show that older people have maintained the tendency to sit in the traditional coffee shops to get their regular taste of beverages, predominantly coffee. This trend shows that coffee shops have a wide range consumer base to choose from, as far as demography is concerned.

The economy of the country has grown significantly and trend indicates that there’s a positive future. Hot drinks sector continue to be popular among the population across the board and thus the purchasing power of coffee is expected to continue rising. The growth of Gross Domestic Product of the country has boosted the consumer buying power, increased the trend of going out. The ability to afford luxury is one thing that has driven the coffee industry, now that this market segment is non-alcoholic zone.

Interestingly, competition has increased significantly, as the country is well organized in terms international trade access. There are diverse races in Saudi Arabia, comprised of Arabs, Asians and people from the west. This kind of diversity has meant that different coffee shops have strived to define their products to suit different market segments. The most common strategy for many of these companies is to diversify their products. Nestle and Starbucks are the dominant multinationals with forays in the Saudi Arabian market, accounting for 23% of the market share (Euro Monitor 2010). Domestic coffee sellers like El Farouk Coffee Center and La Najjar Company, Dr. Café, and others represent 12% of the market share (Euro Monitor 2010).

Dr. Café’s Brand Image

Dr. Café has established a brand name, “Dr. Café@ Café to foster long term memories from their guests, based on high quality products, knowledge about their customers and first class service that reinforces word of mouth marketing strategies. The brand name therefore serves as the focal point for delivering of exclusive products and services in a professional manner to their clients. How does this kind of customer-focused approach to marketing affect the brand image? To answer this question there is a need to explain the concept of brand image in the context of integrated marketing communication.

IMC Elements Used by the Dr. Café

In order to penetrate the market niche and develop a strong brand image, Dr. Café has adopted various integrated marketing communication elements such as advertising, support media, direct marketing, sales promotion, personal selling, public relations and publicity. However, some elements have not been fully integrated in the marketing strategies. The pop-up display of its products online is one way in which they advertise their various products.

To reinforce brand image among coffee consumers, personal selling is used in the marketing initiative where the company has developed a procedure in which they can share personal stories as far as experience with coffee products is concerned. The use of advertising as one of the main marketing elements is especially a common phenomenon aspect of the company. So far, the company advertises its coffee products online, with main channel being through their website and other social networks. Other support media have also been effectively applied in an effort to reach out to a wider section of the market niche.

For example, social networking sites like Facebook and twitter have offered the company opportunity to access many potential customers. Notably, the company has pages with these social networks where they are able to display their products and communicate with clients directly.

Instead of using the conventional channels of advertising like TV commercials, Dr. Café has adopted unconventional marketing strategies where most of its marketing initiatives are done directly to the customers on a one-on-one basis. They reinforce their relationship with the public by forming alliances with other industry stakeholders. This is to ensure there’s a maintained stability in relation to exploitation of resources for long term stability.

However, this initiative is not exhaustive as the company has not engaged much into corporate social responsibility activities that would ensure positive relationship with the people. Although TV commercials have not formed the company’s core channels for marketing, it’s sometimes necessary to use it in order to reach a wider market segment now that the company is expanding its global operations.

Comparison with other Competitors

An ordinary look at the existing companies will easily show that there are some specific brands that are more superior to others, either globally or regionally. For example, US based Starbuck has emerged as a market leader in the global coffee selling industry. While Dr. Café operates mainly in Asian countries, Starbuck and Nestle have wider global presence in many countries allover the six continents. This can be attributed to their increased expansion strategies through franchises that started way back be fore Dr, Café was started. Just like Starbucks, premium pricing strategy is what Dr. Café has used to develop their niche market of luxury consumers.

Like many other coffee sellers like Café Coffee Day, Dr. Café has not only concentrated in coffee beverage selling but has also ventured in coffee accessories to carter for wider needs of their customers. Comparatively, Dr. Café as a brand name has not expanded so much. Its global competitors like Nestle and Starbucks have a global appeal and known brands. But with time, the company is expected to increase its global presence through franchises and become one of the most popular brands. According to Corstjens & Lal (2000), brand image is all about perception, and not reality as one may think.

This therefore means that brands only exist in the minds of the customers; hence management of brands is basically management of perception (Corstjens & Lal, 2000, p.282). Others have argued that failure of some specific brands is associated with their inability to distinguish between operation effectiveness and strategy, thus creating an array of confusion in the execution of brand management (Porter & Lunde, 2002). In a nutshell, there are specific theories that have been applied to explain or guide brand management or brand superiority. These theories allure to the fact that without good strategic plans, it is quite difficult for any industry to weather the market challenges, no matter how big it is in terms of market shares and capital.

Building a strong brand would mean making strategic decisions that are meant to ensure a sustained growth in a market full of competitors (Clarke & Rimmer, 2007). Coffeetime, starbucks, cafecoffeeday, and barniescoffee are the major competitors in coffee selling business in Saudi Arabia. For instance, Starbucks, a multinational company headquartered in the US has established as a market leader through brand name.

According to Porter & Lunde (2002), business decisions would be considered strategic if some aspects of innovations are involved in the management of business units. It is observed that a combined and effective operational strategy lies in the superiority of performance, which is considered a basic aim of any organization that is interested in success. Wrigley (2002) says that a firm can only do better than its competitors if it manages to operate differently as compared to its competitors.

Dr. Café has adopted a strategy where it has exclusively identified its market niche, with the aim of waging off competitors (Fernie & Arnold, 2002). Through the market niche they serve, they have adopted quality product and service as their basis for operation analysis. However, this sole strategy has not managed to fully reinforce the brand name.

Brand value extension of Starbucks is dependent on its product uniqueness in terms of product value. However, according to many studies, successful brand extension is an integrated concept that entails how employees commit themselves to the company, money value, provisions of a variety of products to its customers, and corporate social responsibility (Dragun & Howard, 2003). But a keen look at the Dr. Café’s strategy shows that the company does not have any corporate social responsibility as part of brand building strategy. In fact, corporate social responsibility is known to be one of the major components of integrated marketing communication. The company is expanding through its international forays in other global markets like Singapore and Malaysia (Currah & Wrigley, 2003).

One of the most commonly studied theories of brand management is imitation of business models by other competitors. Some observers have alluded to the fact that Dr. Café has imitated some business models and ideas from Starbucks Coffee. Imitation is an attempt to adopt what other firms had adopted earlier. According to Chang (1995, p.384), such tactics definitely generate a mixed response from their loyal consumers, and eventually degrading the reputation of the leading company. It can therefore be compared with substituting brand identity of the company, which subsequently increases the shift from what the firm is known for.

Brand Personality and IMC

There are three theoretical building blocks of brand personality: personality, expression of self and congruence between brand personality and consumer self (Dawson, 2001). The personality constructs is derived from the cognitive theory of social psychology explaining human personality (Dawson, 2001). Consumers’ attempts to constructs their identity with a brand is widely studied in the field of consumer behavior, and also borrows from the field of psychology as concerns construction of identity. Brand-self congruence is adopted from social psychology and is based on social identification process that consumers engage in with the brands they consume (Evans, Lane & O’Grady, 2002). These three supporting themes can be used to analyze Dr. Café’s establishment as compared to other competitors

One important side of brand personality is based on the construct of what consumers actually feel about the brand. One would consider what brand is more appealing, hence motivates the consumption, which comes with the symbolic benefit of its use (Evans, Lane & O’Grady, 2002). Some studies have strived to focus on the categorization of human personalities from the psychological of brand perception.

Dawson (2001) made an extensive investigation with the aim of identifying which personality traits people associate with a wide range of brands. He concluded that it is possible to transfer the idea of personality dimensions from “human personality psychology to brands and brand management” (Dawson, 2001, p.254). The consumers perception on the brand is seen in the dimension of a possibility that helps it develop into a recognized element.

From the company’s perspective, the brand personality can be uncovered by analyzing the product-related attributes such as brand name, logo, communication style, price, distribution, etc (Dawson, 2001, p.255). Notably, brand image can be unlocked trough research that targets consumers’ perception. This is what Starbucks has consistently done to ensure its brand remains on top of coffee sellers around the globe.

Both the perspective of a consumer and a company add up to the brand personality. Other than more product-specific attributes associated with brand personality, it is also reflected on to the traits attributed to the brand and in the associations, symbolic values as well as emotional responses that the brand receives (Quinn & Alexander, 2002). Sparks (1996) found out that for a brand personality to be successful, it must show a lot of consistency and durability. This could explain why the consistency and durability of Nestle brand continues to lure consumers because they feel close association with the brand at personal level.

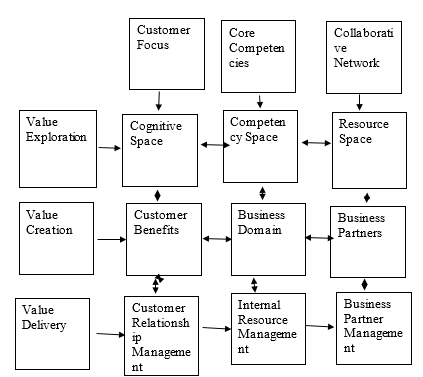

Integrated Marketing Communication through Value Addition

Integrated marketing communication relies on the product and service value. Basically, there are two main reasons for adding value to product and services (Mooij 2010). The first is to enhance consumer benefit, and second is to build business domain. These can be achieved through formation of partnership with other firms, whose roles ensure business objectives and goals are reached.

Diagram 2.

It must be noted that the ability to develop products that appropriately suit customers depends on the firm’s ability to afford the necessary resources. These resources will not only aid the production process but will also help in the distribution process, where the products are expected to reach the target customer at the right place and time. To enhance faster business penetration, Dr. Café has adopted one of the fastest means of communication to reach its target market so as to ensure and faster sales profitability.

Business Partnership and IMC

Dr. Café has adopted one of the most common strategies for retailers and hospitality industry players: partnership and franchising. On its part, the company wants to increase its international market share and strong brand name through franchises and forming partnership with other business around the globe.

In this aspect, it is critical to note that many businesses would find it absolutely difficult to go into partnership with other businesses because of the difference in their divergent needs. Moreover, a firm can only benefit from business partnership if it is able to stand out among its partners as offering the best deal in a particular area of specialization (Hitt & Ireland, 2008). According to Hitt & Ireland (2008), the first step in developing an effective joint marketing strategy is to find out what the other firm need to effectively form marketing strategies. Basically, this would still need assessment of a firm’s internal resources to ensure it has the capacity to develop and offer the needed part for marketing. Dr. Café has endeavoured to expand this strategy and made it as part of their internationalization strategies for business success.

Marketing Communication and customer focus

It is noted that the most important aspect of marketing is focusing on the customers’ needs. This call for a clear and concise cognitive space to ensure the necessary actions is taken care of in the process of marketing. Once the position of the customer has been established, it is important to make them have the benefits they would need to get attracted to in terms of product and services. Basically, Dr. Café has successfully applied this strategy in its efforts to establish its customer base. It’s not surprising the company refer to its clients as “guests” to reinforce a sense of belonging among its customers. The significance of this terminology is to ensure their clients feel that they are being treated like guests and not just ordinary customers.

Many business experts have agreed that there are mainly two strategies that can be used to penetrate international market- standardization according to the local market and differentiating, and market fragmentation. Hitt & Ireland (2008) state, “cultural approaches to internationalization of the product need some relevant promotional mix decisions” (p.21). The first is to establish if the product can be made in line with consumer behavior. That is the company must establish if there is convergence in tastes and a concomitant diminution in the difference in culture of different regions or countries. The second is whether the firm should view globalization as a move away from competition at local as well as regional level to widening the market opportunities in the international arena.

The above view exposes some critical issues in the assessment of consumer tastes and behavior. The first is how products differ in the terms of cultural perception from different regional markets. The second is whether the consumers have free access to the global market or whether there are strong intermediaries that control the supply of the products. Marketing communication can be used to impact on a number of cognitive and behavioral changes that include areas such as repositioning brand, changing misunderstanding, effecting the changes in beliefs and attributing the priorities among other issues.

Similarly, proper research helps managers acquire adequate knowledge for effective marketing communications. The desired communication can also help build brand of a product. Moreover, marketing communication is meant to affect the buyer demand and create brand identity within the goal of building brand image (Travis, 2007). From effective marketing communication, the buyer is able to identify category needs, where they can categorize the products or services that they believe will impact on their motivational state. In this perspective, the buyer will be able to recognize and recall the brand within the set category to ensure there is sufficient reason to make purchase of the product or service.

The increased fragmentation of the modern market has created a situation where marketers are faced with tough decision making processes, especially on how to build and develop a strong business initiative through powerful communication to the target market segment. In Saudi Arabia, different consumer audiences have emerged where Dr. Café targets varied markets segmented by either age or gender.

Product Placement Marketing Communication

Through their retail coffee shops, Dr. Café has endeared itself to establish a serene environment to provide visual appeal to its guests, therefore impacting on their psychological sense of belonging. The company takes a lot of effort to establish its coffee joints so as to provide the luxurious nature of the process.

In this line, the company has adopted some extra services to its clients such as providing wireless internet connections at their joints, designed places to suit family needs and meeting spaces to carter for the needs of various groups. Again, there are stores that provides drive though option as well as patio sitting arrangements for the guests. It is through marketing communication that the Dr. Café can reach the intended market by developing a proper channel of communicating the existing product in the new market. The company has endeared to placing its product in the internet for advertisement as away of communicating the product to the internet users, hence marketing.

They use online placement of products where one can shop online and get the delivery of products done to them as soon as they demand. The adoption of product home delivery is important, particularly in reaching large institutional consumers such as hotels, schools, governmental and non-governmental organizations, etc. This trend has been on a steady rise as internet users increase in number due to emergence of numerous social sites, hence can warranty the desired success.

Dr. Café’s Application of IMC in Promotional Program development

Dr. Café has applied IMC in an effort to enhance promotional program development in many ways. The retail mix approach to develop promotional programs involve many aspects locations, the pricing strategy, advertisements, a strategic design of the stores for easy access and visibility, custom- approach to service , and application of personal selling to the target clients.

When developing promotional programs, the company highlights its strategic locations within the city centres with serene environment to define their appeal strategies. It also uses its assorted products to appeal to the guests. One of the most points highlighted in these promotional initiatives is the fact that its coffee is brewed by The Eva Solo, a renowned coffee brewer whose sexy features are seen as the main attraction to his coffee products. To enhance profitability and maintain the high quality associated with its coffee products, Dr. Café applies premium pricing strategy and ensures expenditures of ads and promos are minimized.

Dr. Café Card and the Marketing Communication

Dr. Café has developed a credit card that can be used to seek service at any of its coffee joints around the world. The card has been designed with an appealing coloration with the intention of giving clients individual specialized treatment. The card gives access to all Dr. Café’s products and services.

The electronic card holder can use it to update his or her account details, and offers the owner an opportunity to get wide arrays of rewards and privileges. Virtually all the products and services offered by Dr. Café can be accessed using the card; hence the brand phrase, “one card no limits”2. This is a step in the right direction for marketing communication strategies for the company.

Strategic Management as a Marketing Communication

Strategic management can be defined as an act of business management technique that helps to formulate, implement, and evaluate some specific critical decisions to reach the organizational objectives (David, 2007). This definition therefore means that strategic management is a type of management inclined towards integrating management process, marking, finance, productions, research and development, and technology in order to reach organizational maximum success (David, 2007; Hill & Jones, 2005). In some occasions, strategic management may be applied in relation or synonymously with the strategic plan of a firm (Hammer & Champy 1993).

However, most common application of strategic management is in the strategy formulation, implementation, and evaluation. That is to say that once a strategic plan is put in place, it takes strategic management initiative to carry out the plan and proceed with the process of implementation and evaluation. One can therefore safely argue that strategic management is to exploit as well as create new and different opportunities for marketing product or services.

Strategic Management Stages and the Concept of IMC

Strategic Formulation

Strategy formulation stage involves developing a vision and mission, establishing the external opportunities and threats of the firm, establishing internal strength and weaknesses of the firm, long term objective establishment, identifying and generating alternative strategies, and finally choosing certain strategies to follow up (Hitt & Ireland, 2008). In this perspective, it is important to note that Dr. Café has managed to establish a marketing communication strategy through establishment of its missions and long term objectives, based on its expansion and product strategies. This is what will guide its managers on certain principles of business reorganizations and marketing.

Some of the formulation process are linked to the ability of the manager to decide on whether to pursue new business opportunities to enter, what business initiatives to drop, how to allocate the available resources to different initiatives, guides the decision on whether to expand certain operations or just diversify, whether to go into the international market, whether to involve the firm into a merger or joint venture initiative (Stahl & Grigsby, 2008; Johnson & Scholes, 2003).

Through such initiatives, the company has acknowledged that one principle of their operational principles is anchored in the belief that they are limited resources to pursue more expansions as fast as they would want to. It therefore means that management of the companies using the brand name, Dr. Café would need to produce best results with the limited resources available. Thus, the franchise strategy-formulation decisions will tie those franchises to produce only certain products, venture into specific markets, use the available resources prudently with an improved technology as a supporting tool over particular period of time and finally maintain the brand image through exemplary services (Yip, 2004).

Strategies also determine long term competitive advantages over time (Warnaby & Woodruffe 1995). Irrespective of the economic situation, strategic decisions have multidimensional consequences and long term effects on the organization’s future. It is through it that top managers are able to get the best perspective to fully conceptualize the effects of their decisions to formulate; and have the authority to weigh on the resources needed to achieve a specific goal of implementation (De Toni & Tonchia, 2003).

Strategy Implementation

In this stage, the managers are expected to establish annual objectives, identify and implement policies, be the motivational factor to employees, and allocate resources such that the strategies that were formulated can be carried out (Drejer 2000). In other words, strategy implementation involves developing a culture that is supportive of the set strategy, creating an effective structure for the organization, refocusing the marketing efforts, budget preparation and development and usage of information systems, and ensuring that the organization’s performance is connected to the employee compensation.

Dr. Café strategy, however, has not implemented the one component of strategy implementation of employee mobilization. It is often considered the action stage of strategic management; it involves the mobilization of employees together with managers to put into action the formulated strategies (Drejer 2000). Recent studies suggest that employees should form the first ambassadors of the company they work for. In most cases, this stage is considered to be the most challenging stages of strategic management. Experts believe that this is the stage where strong personal discipline, commitment, and sacrifice are required (De Toni & Tonchia, 2003; David, 2007).

Acur & Bititci (2004) observe that successful strategy implementation lies in the ability of the manager to motivate his staff, putting a lot of emphasis on both material and emotional motivation. This calls for strong interpersonal skills among the managements and employees alike (Acur & Bititci, 2004). This is because it’s a process that affects all the employees and managers in the organization. Such questions as; what must be done for successful implementation of part of this marketing plan? How can it be done best? In this regard, the challenge involved is to psych up managers and employees to continuously and consistently work towards the set strategic marketing goal.

Strategy Evaluation

Preliminary preview of research materials revealed that Dr. Café has not adopted much of the strategic evaluation of their marketing initiatives. This is the last stage of strategic management. The primary method to establish whether a particular strategy is not working is through evaluation (Porter & Lunde 2002). Evaluation helps the managers establish whether a particular strategy is successful or not. Since external and internal factors continuously affect strategic management; hence marketing, strategy evaluation would help to establish what areas to change or to emphasize (Acur & Bititci, 2004).

The basic activities involved in evaluation are: reviewing of external as well as internal factors is combined to form the base for the present strategies, performance measurements, and taking corrective actions (Acur & Bititci, 2004). Drejer, (2000, p.206) observe that strategy evaluation is necessary because today’s success is not a guarantee of tomorrow’s success; as success will always create unique problems with it, which may be as a result of complacency.

Recommendation

It is evident that Dr. Café has not exhausted all the necessary marketing communication strategies that would be defined as integrated. In lieu to this, I recommend an integrated marketing framework illustrated below.

An Integrated marketing Communication framework

This marketing framework is based on the belief that customers should enjoy products and services offered by companies. To get full benefits of these products and services, the respective providers need to offer them at an appropriate time and place. In some instances, consumers may be privileged to get custom-made products. The value addition delivery means the company will rely on its internal resources to create what its clients really need and desire to have.

The pricing should take care of actual value that can be considered fair if a market segment is focused (Kotler, Jain & Maesincee 2002). It may sound quite simple in theoretical perspective, since all that is required is to create a product that is needed by a particular group of people, put it at the right place regularly frequented by these people, and finally offering the right price. According to this framework, there are several aspects of marketing needed to solve marketing puzzle within the practical sense. The first requirement is to find out what these customers want in terms of product quality, quantity, placement, and pricing. This can be achieved through appropriate market research.

It was established that Dr. Café takes little initiative to market its brand through corporate social responsibilities (CSR). In the recent business environment, it has become apparent that CSR has presented an important aspect of marketing communication. It builds company’s image through involvement into the social courses within the respective communities. There is a need for Dr. Café Company to adopt this collaborative approach to marketing communication with an aim of increasing brand identity. This can be achieved through increased involvement with the celebrities and charitable organizations through organized events.

Globalization and Internationalization of Dr. Café

Dr. Café’s expansion strategies offer another approach to market itself strategically. Although the company has emphasized its strategic marketing initiatives in the domestic market with its customer oriented initiatives, the strategy may not work in the global market. Globalization has compelled many firms to go international in their marketing endeavors. Basically, international market presents significant avenue for the companies to expand their market reach as well as increase profitability. However, it is noted that increased complexity of the international market makes the whole marketing aspect seems like a puzzle.

To penetrate the global market, Dr. Café Company needs more than just customer focus. National wealth in the economically heterogeneous world market and cultural factors determine the economic viability of the marketing strategies that a company would deploy (Hunt, 2002). Secondly, in some fields, the global market is somewhat saturated, creating a form of cut-throat competition within the business environment. In essence, international market’s complexity is compounded by the need to navigate varied socio-political and economic situation in various target countries (Joshi, 2005). It is therefore more logical for Dr. Café to adopt more of the integrated marketing communication in its efforts to successfully market itself internationally.

Sales Promotions as a Marketing Communication

The other strategy is that of collaborative approach to marketing communication involving celebrities. This marketing communication technique is very common in the modern business environment where brand image is associated with personality brands like movie stars and popular musicians.

Saudi Arabian population is not highly heterogeneous. Direct marketing would be a powerful marketing communication tool to provide an edge in an attempt to increase the accessibility of the target market within the country to compete effectively with other coffee sellers. This is because engaging the clustered group of people in terms of language, religion, and culture would be easier. This subsequently calls for more in homogenous approach to advertisement to target specific market segments. For example, the dominant Arabians should be approached in a similar manner, albeit with gender and other fragmentation criteria taken care of adequately.

It is important the company has adopted online marketing strategies as part of its larger marketing efforts. Online marketing is one of the best ways of providing an easy and cheap way of accessing the market, especially through the use of social networking sites.

Studies indicated that international markets needs proper communication between investors, consumers and retailers. In a particular study, it was revealed that many coffee sellers like Nestle had suffered improper relationship within the above highlighted groups of people due to ineffectual and inconsistent communication within the market in the environment (Riera, 2000). Once bad rumors have occurred, the company may find it difficult to eliminate the perception from the minds of the consumers. It is therefore important for the company to initiate a way of addressing any issue that may interfere with its brand identity.

This is to ensure that its brand credibility is build without interference. As has been observed, brand identity can be affected by any form of changes in assortments, how the store is laid out and the pricing strategies. Varley (2005) observe that if any of the change occurs, the customers may find it relatively difficult to “achieve post-integration synergies, and even weaken comparable performance” (p.156).

Studies have indicated hospitality business need access the international market only after strengthening its domestic market through proper integrated marketing communication. It is therefore prudent for Dr. Café to strengthen its domestic market base first (Vida, 2000). If a company fails to develop good reputation at the local level, it is virtually impossible for the good reputation to be established at the international market (Vida, 2000).

Human Resource and IMC

Although Dr. Café’s “foundation fundamentals involves people, system and knowledge” (Dr, Café 2010), their human resources strategy as a component of integrated marketing communication is not clearly stated. Experience in the human capital is needed for any form of success in the retail industry, especially at the international level (Palmer & Quinn, 2003). Palmer & Quinn (2003) state that one way of acquiring good experienced human capital is through the support from collaborative approach to human capital sharing. With this approach, the company would be in a position to deepen its knowledge transfer process and enforce the culture of self-reliance in the market share.

Reference List

Acur, N., & Bititci, U. (2004) “A balanced approach to strategy process”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 24 issue 4, pp.388-408.

Chang, S.J. (1995) International expansion strategy of Japanese firms: capability building through sequential entry, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38 No.2, pp.383-407.

Clarke, I., & Rimmer, P. (2007) The anatomy of retail internationalisation: Daimaru’s decision to invest in Melbourne, Australia, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 17 No.3, pp.361-82.

Corstjens, M. & Lal, R. (2000) Building Loyalty through Store Brands. Journal of Marketing Research, Vol.37, No.3, pp. 281-291.

Currah, A., & Wrigley, N. (2003) The stresses of retail internationalisation: lessons from Royal Ahold’s experience in Latin America, International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, Vol. 13 No.3, pp. 221-43.

David, F. (2007) Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Dawson, J.A. (2001) Strategy and opportunism in European retail internationalization, British Journal of Management, Vol. 12 No.4, pp. 253-66.

De Toni, A., & Tonchia S. (2003) “Strategic planning and firms’ competencies: Traditional approaches and new perspectives”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 23 Issue 9, pp. 947-976.

Dragun, D., & Howard, E. (2003) Value effects of corporate consolidation in European retailing, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 31 No.1, pp.42-54.

Drejer, A. (2000) “Organisational learning and competence development, The Learning Organization”, An International Journal, Vol. 7 Issue 4, pp.206-220.

Dr. Café (2010). Web.

Euro Monitor (2010) Hot Drinks in Saudi Arabia. Web.

Evans, W., Lane, H., & O’Grady, S. (2002) Learning how to succeed in the American market, Business Quarterly, Vol. 157 No.2, pp. 77-85.

Fernie, J., & Arnold, S.J. (2002) Wal-Mart in Europe: prospects for Germany, the UK and France, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 30 No.2, pp. 92-102.

Hammer, M. & Champy, J. (1993) Reengineering the Corporation, Harper Business, New York.

Hill, C., & Jones G. (2005) Strategic Management: An Integrated Approach, Boston. Wiley Publishers.

Hitt, M., & Ireland, D. (2008) Strategic Management: Competitiveness and Globalization, Concepts and Cases. London. London School of Economics.

Hunt, S. (2002) Foundations of Marketing Theory: Toward a general theory of marketing. London. M.E. Sharpe.

Johnson, G., & Scholes, K. (2003) Exploring Corporate Strategy, 6th ed., Prentice Hill: London.

Joshi, M. (2005) International Marketing. New York. Oxford University Press.

Kotler, P. Jain, D., & Maesincee, S. (2002) “Formulating a Market Renewal Strategy,” in Marketing Moves (part 1) Fig 101. Boston. Harvard Business School Press, p. 29.

Mooij, M. (2010) Global Marketing and Advertising: Understanding Cultural Paradoxes. London. Sage Publishers.

O’Grady, S., Lane, H.W. (2006) The psychic distance paradox, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 27 No.2, pp.309-34.

Palmer, M., Quinn, B. (2003) The strategic role of investment banks in the retail internationalisation process: is this venture marketing? The European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 37 No.10, pp.1391-408.

Porter, A., & Lunde, P. (2002), Trade and Travel in the Red Sea Region: Proceedings of Red Sea Project. New York. Sage Publisher.

Quinn, B. & Alexander, N. (2002) International retail divestment, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 30 No.2, pp.112-25.

Riera, J. (2000), Tesco sourcing teams to drive down global costs, The Retail Week, No.17, p.1.

Stahl, M., & Grigsby, D. (2008) Strategic Management: Total Quality and Global Competition, New York. Wiley Publishers.

Sparks, L. (1996) Investment recommendations and commercial reality in Scottish grocery retailing, The Services Industries Journal, Vol. 16 No.2, pp.165-90.

Travis, T. (2007) Doing Business Anywhere: The Essential Guide to Going Global. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Varley, R. (2005) Retail Product Management: Buying and Merchandising. London. Routledge Publishers.

Vida, I. (2000) An empirical inquiry into international expansion of US retailers, International Marketing Review, Vol. 17 No.4/5, pp.454-75.

Wrigley, N. (2002) The landscape of pan-European food retail consolidation, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 30 No.2, pp.81-91.

Warnaby, G. & Woodruffe, H. (1995) “Cost Effective Differentiation: an Application of Strategic Concepts to Retailing”, International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp.253-270.

Yip, G. (2004) “Using Strategy in Change Your Business Model”, Business Strategy Review, Vol. 15 Issue 12, pp. 17-24.