Abstract

The past two decades have placed much emphasis on sustainability practices within different industries. In 2017, half of the top 100 fashion brands implemented a sustainable approach in their practices (McKinsey, 2017). Fashion as an industry highlights sustainability is a part of its social and environmental movements. Conversely, emphasis on sustainability from the consumer perspective has been a mainstream issue. Consumers are constantly drawn to companies with clear sustainable practices and products. Yet, companies have constantly fallen short of upholding their socially responsible image in front of the public eye.

Widespread societal concern that firms are disseminating false or ambiguous environmental information has led to a growing number of customers becoming skeptical about the environmental performance and benefits of green products. Previous research has considered how skepticism might have a detrimental effect on consumer responses (Annamma, Sherry, Venkatesh, Wang, & Chan, 2012). Other studies identify several barriers consumers might face when purchasing sustainable products. Therefore, there exists a need for a better understanding of how skepticism affects green purchase behavior (Wunker, 2017).

This study will identify consumer perception barriers of green purchasing behavior and examines the effect of these barriers towards CSR practices. Moreover, consumer perception influences consumers’ attitudes towards purchasing. Specifically, this research considers consumer perception on purchasing decision and word of mouth intention. To set a scope to this study, the target group will be the young consumers (between 18 and 35 years old) who live in The Netherlands and purchase sneakers from Nike and Adidas. A quantitative methodology through questionnaires will be used to collect primary data and the result will be analyzed by SPSS software.

List of Abbreviations

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

- Word Of Mouth (WOM).

- Parley x Footwear (Px-F).

- Plant-Based Footwear (P-BF).

- Footwear Sustainability Index (FSI).

- Air Sole Innovation (ASI).

Introduction

Study background

In the past two decades, business sustainability has gathered much attention from both academics and practitioners across different industries all over the world (Turker & Altuntas, 2014). Sustainability is an integral aspect of businesses because it promotes prudent utilization of resources and markets companies. While the topic has gained much controversy, most businesses consider sustainability essential for their practices.

The three dimensions of sustainability have been referred to as the Triple-Bottom-Line, seeks to address social, economic, and environmental issues (Govindan, Khodaverdi, & Jafarian, 2013). In order to improve a sustainable business, firms must create Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies, through designing policies that integrate environmental, social, and ethical rights into business operations.

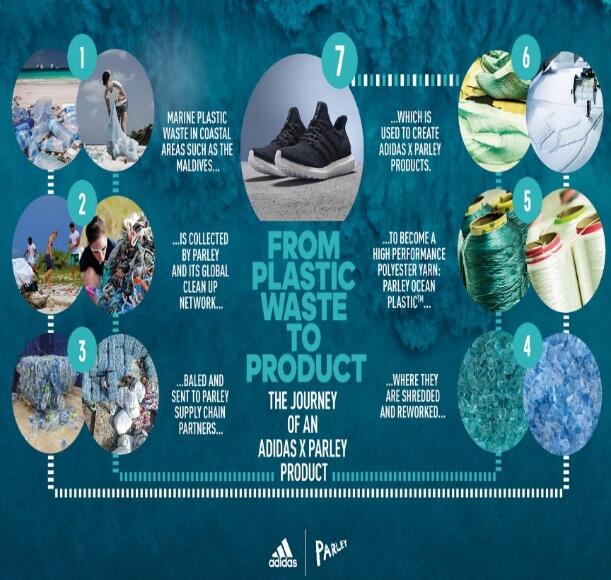

A company’s association with environmental issues determines its reputation (Caplan, 2003). Due to this fact, more fashion companies are taking sustainability into consideration (Choi & Cheng, 2015). Adidas and Nike, for example, have stepped up seriously. Adidas has created a greener supply chain, eliminated plastic bags, and participated in different sustainable projects. Their cooperation with Parley allows Adidas to use recycled ocean plastic and yarn to produce new products “Parley x Footwear” (Px-F) (Amir, 2018). Nike, however, pursues sustainability by reducing the amount of toxins released from its production lines.

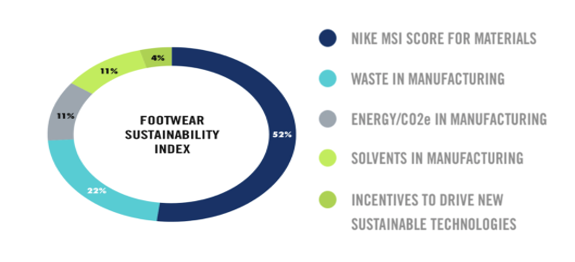

By using the Considered Index, designers can manage a shoe’s environmental effect throughout the design operation. Adidas also introduced the Plant-Based Footwear (P-BF), in its strategy, which increased their CSR perception. In addition, Nike introduced Footwear Sustainability Index (FSI) and Air-Sole Innovation (ASI), allowing the company to measure the environmental impact of each product (Appendix 2).

These companies have earned large amount of loyal customer bases because of their sustainability efforts (McKinsey, 2017). According to CGS’s findings, brand loyalty is related to product quality; however, the second-highest reason consumers return to a specific brand is its sustainable practices (Sungchul & Ng, 2011). Thus, fashion companies can fiercely compete in their market by implementing sustainability into their strategy.

Several barriers affect purchasing decision regarding sustainable products. Skepticism is one of the barriers that hinder consumers from choosing green products in the market (Wunker, 2017). Consumer skepticism is defined as “the consumer’s tendency to question any aspect of a firm’s activities” (Morel & Pruyn, 2003, p. 352). Consumer’s skepticism appears when firms spread ambiguous environmental information regarding the sustainability initiative and environmental performance. A study by Yiridoe et al. (2005) suggested that consumer’s skepticism on green products appear from mislabeling, misinterpretation, and misrepresentation of green products.

Thus, even though consumers may want to buy green products, skepticism about environmental performance may hold them back from doing so. One essential aspect of CSR is preventing skepticism (Fuentes, 2018). Kwong and Balaji (2016) assert that skepticism has a negative impact on consumer purchase intentions. Yet, there is a need for a deeper understanding of how skepticism affects the green purchase decision. Fashion firms need to overcome consumer skepticism as it can influence consumers’ purchasing decisions, which can place a company at a disadvantage.

Problem statement

As competition rises among shoemakers (World Trade Organization, 2018), an increasing number of companies tend to adopt sustainability practices. However, a recent study shows that consumers may not be willing to buy green products because of their skepticism (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). According to Bronn and Vrioni (2001), since more firms engage in CSR, consumer skepticism is rising.

When consumers doubt greenness of company’s products, consumers might shift to other brands or spread negative word of mouth (WOM), which negatively affects a company’s reputation (Shim & Yang, 2016; Zeynep & Atik, 2015). According to the latter, firms must change this ‘negative attitude’ in consumers’ behavior. However, this creates a challenge for fashion companies since their practices need to be communicated clearly to consumers without generating skepticism, specifically in the case of Nike and Adidas.

Research aim

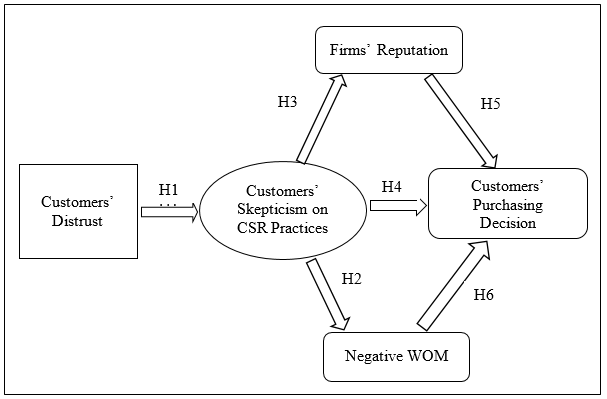

The purpose of this paper is to study consumers’ perception of sustainability practices of Adidas and Nike. The research aims to model how consumers’ distrust contributes to the occurrence of skepticism on CSR practices. Moreover, the study seeks to demonstrate how skepticism on CSR practices influences firms’ reputation, which in turn determines the purchasing decision of customers in the sneakers industry. Subsequently, the study models how corporate reputation and negative WOM affect the purchasing decision of consumers. As a beneficial aspect, this paper aims to develop insights on how consumers’ perception of CSR practices influences their purchasing behavior. Insights from the ‘suspicion’ of consumers, aids in the improvement of the CSR practices of footwear companies like Adidas and Nike.

Literature review

Dimensions of sustainability

Sustainability is an important issue nowadays for success (Haanaes, 2016). Several global fashion companies introduce sustainable initiatives, including Adidas and Nike (Payseno, 2018). Williams and Millington (2004) define sustainable development “as the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (p. 100). There are three major dimensions of sustainability, which are referred to as the triple bottom line (Govindan et al., 2013; Williams & Millington, 2004).

According to a study by Dahlsrud (2008), there are many available definitions of CSR. The definition from Crane (2013) is useful, namely “CSR is defined as the way organizations combine economic, social, and environmental concerns into their values and operations in a transparent and accountable manner.” The definition emphasizes the social, environmental, and economic imperatives, which can be referred to the triple bottom line approach.

Barriers to sustainable consumption

Nowadays, consumers understand the importance of sustainability, but several barriers affect purchase intention (Bonini & Oppenheim, 2008; Wunker, 2017). Additionally, the study by Joshi and Rahman (2015) mentioned that there is a weak link between consumers’ green attitudes and purchasing behavior, which is referred to as ‘attitude-behavior-gap’. Bonini and Oppenheim (2008) studied more than 7000 consumers in eight major economies and concluded that 87% of consumers were concerned about the social and environmental influences of the goods purchased. Yet, when it comes to buying green goods, only 33% of these consumers admitted they should buy green goods.

One reason behind this is consumers’ skepticism regarding CSR initiatives. Morel and Pruyn (2003) defined consumer skepticism regarding CSR initiatives as “consumer’s tendency to question any aspect of a firm’s CSR activities.” Additionally, according to Webb and Mohr (1998), skepticism occurs when consumers question and distrust a company’s CSR practice. Distrust of green fashion can be seen as a negative perception based on lack of awareness and understanding. Thus, an insight into the perception of consumers towards green fashion is necessary to remedy distrust as a barrier.

Distrust and CSR perception

Since the second half of the 20th century, long debate on CSR has been taking place, since then firms always mention social responsibility as a part of their sustainable practice (Rosenbaum & Wong, 2015). However, customers fail to determine whether companies pursue this to gain profit or a genuine desire to be sustainable. Skepticism stems from distrust of advertising assertions that organizations make regarding their products (Obermiller & Spangenberg, 2013; Kwong & Balaji, 2016). Since companies want to expand their market share and retain customers, they have to exploit diverse opportunities for advertising.

However, consumers develop distrust when they realize that the quality of products do not match attributes that companies advertise. According to Morel and Pruyn (2003), distrust relates to skepticism because when consumers are skeptical, they doubt the information of products they intend to purchase. In this case, adverts made by Adidas and Nike are prone to distrust, leading to ‘green skepticism’ on CSR practices. Thus, the following alternative hypothesis (H1) predicts the effects of customers’ distrust on skepticism on CSR practices.

- H1: Customers’ distrust is a positive predictor of skepticism on CSR practices.

CSR perception and WOM

The interaction between organizations and customers influence the perception of CSR practices. According to Wang (2018), WOM comprises both negative and positive statements that customers or potential consumers share and influence the perception of products and services offered by companies. Previous studies show that consumer skepticism contributes to the occurrence of negative WOM because it influences attitudes, purchasing intentions, and brand image (Balaji, Khong, & Chong, 2016; Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013).

The dialogic theory holds that effective interaction between organizations and customers creates robust channels of communication, alleviates distrust, and causes the spread of positive WOM (Uysal, 2018). Hence, firms need to diminish the level of distrust and skepticism among customers to prevent the spread of negative WOM about company’s CSR practices (Servaes & Tamayo, 2013). In this case, consumer skepticism affects the perception of CSR, resulting in the occurrence of negative WOM. As a result, the following alternative hypothesis (H2) was formulated:

- H2: Consumer skepticism on CSR practices is a positive predictor of negative WOM.

CSR perception and firm reputation

Reputation plays a central role in organizations because it determines the impact of marketing strategies. The attribution theory postulates that the way customers perceive, belief, and trust CSR practices influences the reputation of organizations (Chen & Chiu, 2018). According to Rim and Kim (2016), corporate reputation has an intricate link with the perception of CSR practices. In essence, the kind of reputation that companies have in competitive markets relies on the nature of CSR practices espoused. When customers distrust CSR practices, they acquire a negative perception of firms and develop skepticism. Previous studies found out that consumer skepticism has a negative influence on the way consumers perceive the company’s reputation (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore, & Hill, 2006; Ellen, Webb, & Mohr, 2006; Elving, 2013).

Consumers may believe that companies take advantage of CSR practices to increase their profits (Kim & Lee, 2009). Skepticism towards firms’ CSR practices, lead to a deterioration of its corporate reputation (Shim & Yang, 2016). Therefore, the second alternative hypothesis (H3) was formulated:

- H3: Consumer skepticism on CSR practices is a negative predictor of corporate reputation.

CSR and purchasing decision

According to Dawson (2006), purchasing behavior comprises of attitudes that determine the way consumers choose products, select brands, and undertake their shopping. A purchase decision is the result of each of these factors, and thus, it is useful for firms to collect information regarding consumers’ choices and utilize them to improve their offering. Dewey (2012) established that the process of purchasing constitutes the following five phases (Figure 1). Before making a purchase decision, customers recognize the problem, search appropriate information, and evaluate available alternatives.

This study investigating if consumers are skeptical towards the green sneakers offered by both Adidas and Nike, this study goes a step further of Kwong and Balaji (2016), which aimed to investigate the role of skepticism in green purchase behavior. The study of Kwang provides results from a study in which it has been investigated whether skepticism of organic labels influences consumers’ purchasing intentions of organic products.

Kwang study was limited as it was conducted in Malaysia, this study found that consumers’ skepticism of organic labels has a negative impact on purchase intention, and negatively related to future purchase intentions. Therefore, this research aims to determine whether the consumers’ skepticism in the sneakers segment is related to the green purchase decision. Hence, the following alternative hypothesis (H4) was formulated:

- H4: Consumer’s skepticism towards CSR practices affects the purchasing decision of green sneakers.

Firms’ reputation and purchasing decision

Firms’ reputation and consumers’ purchase decisions have a direct relationship, which explains the association between brand image and consumer behavior. According to the theory of reasoned action, consumers evaluate qualities of organizations, brands, and products before making the critical decision of purchasing of a given product (Mi, Chang, Lin, & Chang, 2018). CSR practices that create a positive brand image of an organization encourage consumers to purchase products of choice.

An empirical study performed among 212 chief executive officers of various organizations revealed that corporate reputation enhances brand attitudes, increases consumer awareness, and promotes preferences of products (Jung & Seock, 2016). However, marketing managers ought to be wary of the impact of negative reputation on the attitudes and purchasing decisions of customers. Jung and Seock (2016) advise organizations and marketing managers to avert negative reputation because it creates negative attitudes and aggravates purchasing decisions of customers. Thus, the theory of reasoned action explains the relationship between corporate reputation and the purchasing decision of consumers.

Further analysis of the literature shows that the reputation of organizations plays a significant role in customer satisfaction and subsequently determines the purchasing decisions. Reputable organizations tend to satisfy their customers, and thus attract and retain them for a long time. In their study done among 300 Saudi organizations, El-Garaihy, Mobarak, and Albahussain (2014) established that corporate reputation mediates the impact of CSR practices on the competitiveness of an organization. This finding shows that the purchasing decision is a direct effect of firms’ reputation and an indirect effect of CSR.

In the current world where competition is key for the survival and growth of businesses, organizations focus on building a competitive reputation in their target markets. Hanaysha (2018) argues that organizations use CSR to create a positive brand image in the market aimed at influencing consumer behavior and purchasing decisions in favor of their products. Burke, Dowling, and Wei (2018) recommend that market managers should employ reputation as a marketing strategy because it enhances understanding of the company’s brands among customers and influences their purchasing decisions. Therefore, the study formulated the hypothesis that:

- H5: Firms’ reputation is a positive predictor of the purchasing decision of green sneakers.

Negative WOM and purchasing decision

The spread of knowledge and information is a critical aspect of marketing that determines the purchasing behavior of consumers. Before the advent of information technology, WOM has been a major method that companies utilize in sharing knowledge and information about products. When customers consume certain products, they share knowledge and information regarding their quality and brand of the organization, which influence attitudes and views among potential consumers (Vallejo, Redondo, & Acerete, 2015). In essence, the conversation that emanates from the sharing of knowledge and information influences the purchasing decision of customers.

According to Fu, Ju, and Hsu (2015), varied antecedents determine if consumers engage in either positive WOM or negative WOM. Depending on the quality of products and relationship with companies, consumers have varied drivers of WOM. Fu et al. (2015) assert that distributive justice drives the negative WO, whereas interactional justice drives positive WOM. Hence, negative WOM have undesirable effects on the purchase decisions of customers.

Owing to increased competition, companies have realized that customers spread information and knowledge of their products and reputation using WOM. A survey conducted among 1200 consumers in Jordan demonstrated that negative WOM is a statistically significant predictor of the purchasing decisions (Zamil, 2011). The quality of products and the nature of relationships that companies cultivate with their customers have a marked impact on the purchasing decisions.

Ahmad, Vveinhardt, and Ahmed (2014) surveyed 100 students in Pakistan and found out that WOM is a key factor that allows making of informed purchasing decisions of certain products in the market. Essentially, WOM enables customers to share their attitudes, experiences, ideas, and beliefs in their routine aspects of social communication. The advancement in information technology has led to the emergence of electronic WOM where consumers spread negative and positives of products and companies on the Internet or various social platforms (Potural & Turkyilmaz, 2018). Comparative analysis shows that negative WOM has a higher impact on the purchasing decision than positive WOM (Hornik, Satchi, Cesareo, & Pastore, 2015). Therefore, the study posed the following hypothesis:

- H6: Negative WOM is a negative predictor of the purchasing decision of green sneakers.

Conceptual model

Figure 2 is the conceptual model that depicts relationships between variables of the study and the placements of the six hypotheses. The conceptual model indicates that consumers’ distrust influences CSR skepticism (H1), which in turn determines WOM (H2), firms’ reputation (H3), and purchasing decision (H4). Furthermore, the conceptual framework indicates that both firms’ reputation (H5) and negative WOM (H6) influence customers’ purchasing decision. The conceptual model indicates that consumers’ distrust is an independent variable that determines consumer’s skepticism on CSR practices. As an independent variable, consumers’ skepticism on CSR practices directly affects WOM, firms’ reputation, and purchase decisions. Subsequently, firms’ reputation and negative WOM independent variables that have a direct effect of the purchasing decisions of customers.

Research questions

The overall research question is that what are the direct and indirect impacts of customers’ distrust, consumers’ skepticism regarding CSR practices (Adidas & Nike), consumers’ reputation, and negative WOM on the consumers’ purchase decision in the sneakers industry?

Specific research questions in line with hypotheses are:

- What is the relationship between consumers’ distrust and skepticism on CSR practices regarding sneakers industry?

- How does consumer skepticism on CSR practices influence the WOM among sneakers’ consumers?

- How does consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices influences firms’ reputation?

- How does consumer skepticism on CSR practices influence the green purchasing behavior in sneakers’ consumers?

- What is the effect of firms’ reputation on consumer’s purchase decision?

- What is the effect of negative WOM on consumer’s purchase decision?

Methodology

Data collection

This study will follow a quantitative method to study attitudes, behaviors, and other variables from a large sample population (DeFranzo, 2011). Furthermore, a quantitative method will identify the perception of samples on the variable ‘consumer skepticism on CSR practices’, which linked to the barrier ‘distrust’ from the literature review. Based on the aim of the study, a survey can lead to participating more customers as samples for collecting data.

The two shoemakers (Adidas and Nike) will be the main focus, with their ‘BCI’, ‘P-BF’, and ‘FSI’, ‘ASI’ sustainability line of green sneakers. These lines will be tested by consumers in the sneaker segment according to the level of skepticism towards CSR practices, and whether these variables will affect their purchase decision and their WOM intention of green sneakers. A cross-sectional survey will be used to identify these relationships.

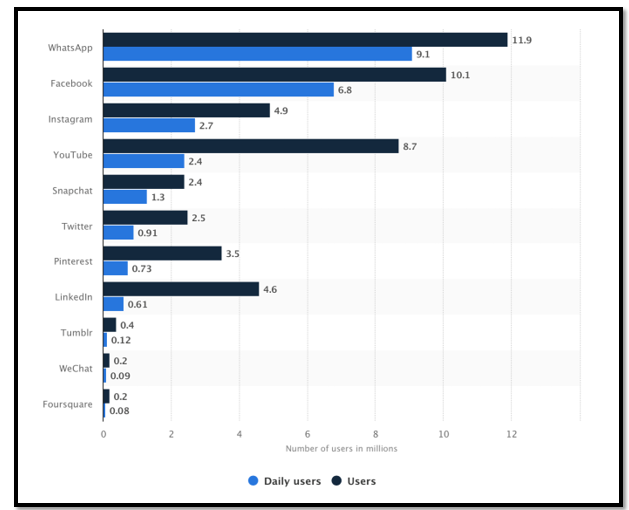

The survey questions, including multiple-choice questions will be formulated with an online tool ‘Thesis tools Pro’ and will spread through social media channels and at Dutch Universities. The questionnaire will be sent to the participants using social media channels with an online tool ‘SurveyMonkey’, and the data can be tested in SPSS software (Collis & Hussey, 2014). This research uses social media platforms such as Facebook messages and WhatsApp as they are the most used platforms in The Netherlands (Statista, 2019) (Appendix 5).

Population and sample

The target group in this survey is the young consumers between 18 and 35 years old who live in The Netherlands; however, they can have a different nationality. The age group (between 18 and 35) is more open to change compared to other ages and the most enthusiastic about keeping up with the latest fashion trend (Farsang, 2014). According to demographics, people in the age group 16-35 years consist of approximately 4 million of the current population of the Netherlands (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2018), which is too large to investigate. With a population of 4 million, the margin of error of 5%, and the confidence interval of 95%, the appropriate sample size should be at least 384 respondents (Jani, 2014).

The author will try to reach at least 400 respondents. Participants will be contacted through the random sampling technique. The participants will receive a link to the online questionnaire through social media platforms. A short definition of sustainable practice in sneakers industry with some examples will be given to the respondents at the very beginning of the questionnaire, to ensure that the participants are aware of the purpose of this study.

Data analysis

After cleaning data using Excel program, the data will be entered to SPSS software to manage the analysis of the survey results. T-test, one-way ANOVA, and multiple regression are inferential statistics that will be used to assess data that will be collected through a questionnaire survey. The demographic variables will be the control variables. These variables will be researched because previous research mentioned that these variables show significant differences in purchasing decision (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). In order to ensure that the respondents live in the Netherlands and belong to the age group (18-35) as required, a control question will be asked at the beginning of the questionnaire.

Furthermore, controlling questions will be asked in the beginning to test whether participant read the questions correctly and to increase the internal reliability. T-test and one-way ANOVA will be used to analyze the impact of demographics. Multiple regression will be used to test whether the independent variables affect the dependent variables (Mertler & Reinhart, 2017). By doing this, the author can investigate if the consumers’ skepticism on CSR practices in the sneakers industry influences WOM, firms’ reputation, and green purchase decisions.

Validity and Reliability

To ensure validity, the study will utilize well-designed survey instruments with appropriate questions and scope. According to Trochim, Donnelly, and Arora (2016), researchers should ensure that surveys meet content validity, criterion validity, and construct validity. To achieve content validity, the study will seek expert review of research instrument before administering to respondents to ensure that it covers distrust, CSR skepticism, WOM, firms’ reputation, and purchasing behavior.

Given that experts have extensive knowledge about CSR, critical assessment of the survey questions to ascertain if their contents meet the required aspects of the research is necessary. Since there are established instruments that measure variables of interest, the study will correlate them with the designed variables to determine the criterion validity of the research instrument (Field, 2017). Comparative assessment of the questionnaire will indicate if it offers a valid alternative of measuring variables of interest in the study. The study will also use factor analysis and principal component analysis to evaluate the construct validly Likert items used in the measurement of various variables.

Field (2017) explains that factor analysis and principal component analysis eliminate redundant variables and enhance construct validity. Therefore, by ensuring that the research instrument meets content validity, criterion validity, and construct validity, the collected data will have a high level of validity. In sampling, the study will ensure external validity using the random method to eliminate researchers’ bias and attain a representative sample size.

To enhance the reliability of the study, the study will test data collected using the designed research instrument. Internal consistency and test-retest are two forms of reliability techniques that the study will use (Field, 2017). The study will use internal consistency in assessing the reliability of Likert items of the critical variables of interest. The assessment of the internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha will check if respondents have a similar understanding of research questions and provide dependable answers. In the analysis of the internal consistency reliability, the study will use Cronbach’s alpha and consider values that are greater than 0.7 as reliable (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Moreover, Pearson correlation will be used in the evaluation of test-retest reliability. A strong correlation coefficient that is greater than 0.8 will be considered reliable in measuring variables of interest (Field, 2017). In test-retest reliability, a strong correlation means that variables do not deviate significantly from one time to another owing to differences in conditions of the study.

References

Adidas Group. (2019). Sustainable and Recycled materials. Web.

Ahmad, N., Vveinhardt, J., & Ahmed, R. (2014). Impact of word of mouth on consumer buying decision. European Journal of Business and Management, 6(31), 394-403.

Annamma, J., Sherry, J. F., Venkatesh, A., Wang, J., & Chan, R. (2012). Fast fashion sustainability and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fashion Theory, 16(3), 273-295. Web.

Balaji, M. S., Khong, K. K., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2016). Determinants of negative word-of-mouth communication using social networking sites. Information & Management, 53(4), 528-540. Web.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on the consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46-53.

Bonini, S., & Oppenheim, J. (2008). Cultivating the green consumer. Web.

Bronn, P. S., Vrioni, A. B. (2001). Corporate social responsibility and cause-related marketing: An overview. International Journal of Advertising, 20(2), 207-222. Web.

Burke, P., Dowling, G., & Wei, E. (2018). The relative impact of corporate reputation on consumer choice: Beyond a halo effect. Journal of Marketing Management, 34(13), 1227-1257. Web.

Caplan, A. (2003). Reputation and the control of pollution. Ecological Economics, 47(2-3), 197-212.

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Trends in the Netherlands 2018. Web.

Chen, B. H., & Chiu, W. (2018). The relationship among consumer attributions, consumer skepticism, and perceived corporate social responsibility in Taiwan. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 10(1), 29-38. Web.

Choi, T., & Cheng, E. (Eds.). (2015). Sustainable fashion supply chain management: From sourcing to retailing. New York, NY: Springer.

Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2014). Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate & postgraduate students. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1-13. Web.

Dawson, J. F. (2006). The retailing reader. London, England: Routledge.

DeFranzo, S. (2011). What’s the difference between qualitative and quantitative research. Web.

Dewey, J. (2012). How we think. North Chelmsford, MA: Courier Corporation.

El-Garaihy, W. H., Mobarak, A. K. M., & Albahussain, S.A. (2014). Measuring the impact of corporate social responsibility practices on competitive advantage: A mediation role of reputation and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Business and Management, 9(5), 109-124. Web.

Ellen, P. S., Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (2006). Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 147-157. Web.

Elving, W. J. L. (2013). Skepticism and corporate social responsibility communications: The influence of fit and reputation. Journal of Marketing Communication, 19(4), 277-292. Web.

Farsang, A. G. (2014). Survey results on fashion consumption and sustainability among young consumers in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the UK and the US in 2014. Web.

Field, A. P. (2017). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publisher.

Fu, J., Ju, P., & Hsu, C. (2015). Understanding why consumers engage in electronic word-of-mouth communication: Perspectives from theory of planned behavior and justice theory. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14(6), 616-630. Web.

Fuentes, M. G. (2018). Avoiding CSR skepticism through brand reputation and brand-cause fit enhancement. Web.

Govindan, K., Khodaverdi, R., & Jafarian, A. (2013). A fuzzy multi-criteria approach for measuring sustainability performance of a supplier based on triple bottom line approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 47(1), 345-354. Web.

Haanaes, K. (2016). Why all businesses should embrace sustainability. Web.

Hanaysha, J. (2018). An examination of the factors affecting consumer’s purchase decision in the Malaysian retail market. PSU Research Review, 2(1), 7-23. Web.

Hornik, J., Satchi, R. S., Cesareo, L., & Pastore, A. (2015). Information dissemination via electronic word-of-mouth: Good news travels fast, bad news travels faster! Computers in Human Behavior, 45(1), 273-280.

Ismael, A. (2018). Adidas sold 1 million pairs of sneakers made from ocean waste in 2017 — now the company is introducing a line of recycled clothing and taking steps to become even more sustainable. Web.

Jani, P. N. (2014). Business statistics: Theory and applications. New Delhi, India: PHI Learning.

Joshi, Y., & Rahman, Z. (2015). Factors affecting green purchase behavior and future research directions. International Strategic Management Review, 3(1-2), 128-143. Web.

Jung, N. Y., & Seock, Y. (2016). The impact of corporate reputation on brand attitude and purchase intention. Fashion and Textiles, 3(20), 1-15. Web.

Kim, S. B., & Kim, D. Y. (2016). The influence of corporate social responsibility, ability, reputation, and transparency on hotel customer loyalty in the US: A gender-based approach. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 1-13. Web.

Kim, Y. J., & Lee, W. (2009). Overcoming consumer skepticism in cause-related marketing: The effects of corporate social responsibility and donation size claim objectivity. Journal of Promotion Management, 15(4), 465-483. Web.

Kwong, G. S. & Balaji, M. S. (2016). Linking green skepticism to green purchase behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 131(1), 629-638. Web.

McKinsey. (2017). The state of fashion. Web.

Mertler, C. & Reinhart, R. V. (2017). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Practical Application and Interpretation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Mi, C., Chang, F., Lin, C., & Chang, Y. (2018). The theory of reasoned action to CSR behavioral intentions: The role of CSR expected benefit, CSR expected effort, and stakeholders. Sustainability, 10(4462), 1-17. Web.

Morel, K., & Pruyn, A. (2003). Consumer skepticism toward new products. European Advances in Consumer Research, 6(1), 351-358.

Nike. (2018). Sustainable business performance summary. Web.

Obermiller, C., & Spangenberg, E. R. (2013). Ad skepticism: The consequences of disbelief. Journal of Advertising, 34(3), 309-324. Web.

Payseno, K. (2018). Top 20 corporate social responsibility initiatives of 2018. Web.

Potural, M., & Turkyilmaz, M. (2018). The impact of eWOM in social media on consumer purchase decisions: a comparative study between Romanian and Bosnian consumers. Management and Economics Review, 3(2), 138-160.

Rosenbaum, M. W., & Wong, I. A. (2015). Green marketing programs as strategic initiatives in hospitality. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(2), 81-92. Web.

Servaes, H., & Tamayo, A. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: The role of customer awareness. Management Science, 59(5), 1045-1061. Web.

Shim, K. & Yang, S. (2016). The effect of bad reputation: The occurrence of crisis, corporate social responsibility, and perceptions of hypocrisy and attitudes toward a company. Public Relations Review, 42(1), 68-78. Web.

Skarmeas, D., & Leonidou, C. (2013). When consumers doubt, watch out! The role of CSR skepticism. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1831-1838. Web.

Statista. (2019). Number of individuals using the leading social media platforms in the Netherlands in 2018, by social network (in million users). Web.

Sungchul, C., & Ng, A. (2011). Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(2), 269-282. Web.

Trochim, W. M. K., Donnelly, J. P., & Arora, K. (2016). Research methods: The essential knowledge base. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Turker, D., & Altuntas, C. (2014). Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. European Management Journal, 32(5), 837-849. Web.

Uysal, N. (2018). On the relationship between dialogic communication and corporate social performance: advancing dialogic theory and research. Journal of Public Relations Research, 30(4), 1-15. Web.

Vallejo, J. M., Redondo, Y. P., & Acerete, A. U. (2015). The characteristics of electronic word-of-mouth and its influence on the intention to repurchase online. European Journal of Business Management and Economics, 24(1), 61-75.

Wang, J., Wang, L., & Wang, M. (2018). Understanding the effects of eWOM social ties on purchase intention: A moderate mediation investigation. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 28(1), 54-62. Web.

Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (1998). A typology of consumer responses to cause-related marketing: From skeptics to socially. Journal of Public Policy Marketing, 17(2), 226-238. Web.

Williams, C. C., & Millington, A. C. (2004). The diverse and contested meanings of sustainable development. The Geographical Journal, 170(2), 99-104. Web.

World Trade Organization. (2018). Competition policy, trade and the global economy: Existing WTO elements, commitments in regional trade agreements, current challenges and issues for reflection. Web.

Wunker, S. (2017). 10 obstacles to new product success. Web.

Yiridoe, E. K., Bonti-Ankomah, S., & Martin, R. C. (2005). Comparison of consumer perceptions and preference toward organic versus conventionally produced foods: A review and update of the literature. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 20(4), 193-205. Web.

Zamil, A. (2011). The impact of word of mouth (WOM) on the purchasing decision of the Jordanian consumer. Research Journal of Internatıonal Studıes, 20(1), 24-29.

Zeynep, O. E., & Atik, D. (2015). Sustainable markets: Motivating factors, barriers, and remedies for mobilization of slow fashion. Journal of Macromarketing, 35(1), 53-69. Web.

Appendices

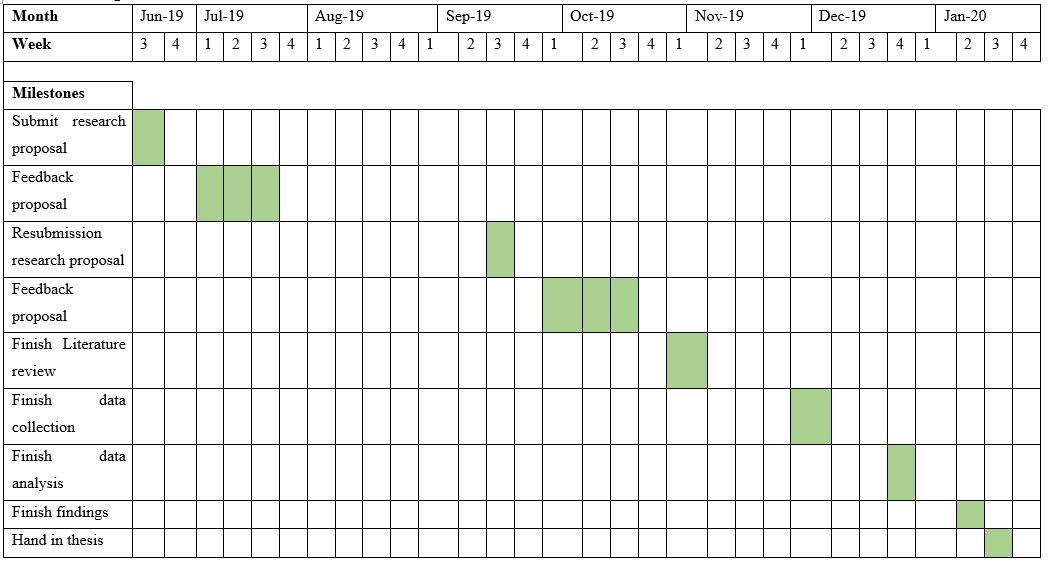

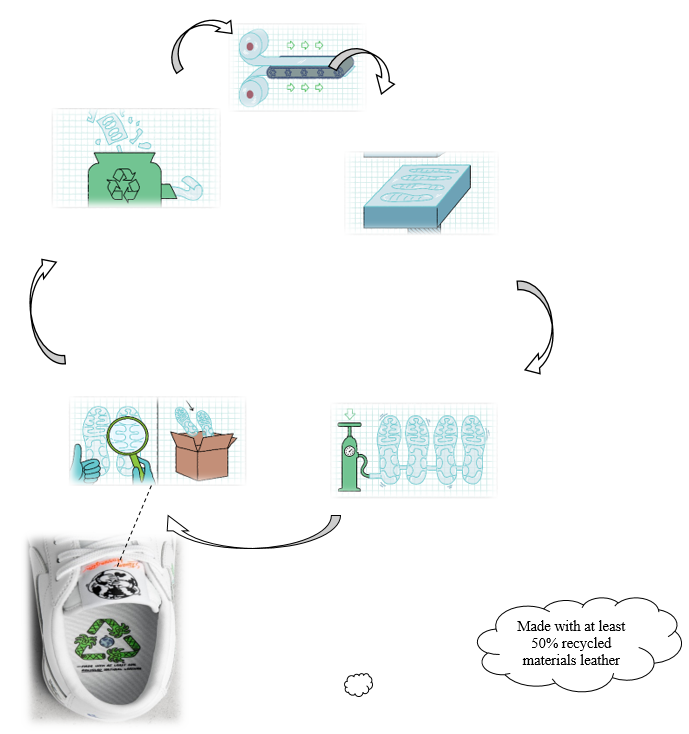

Appendix 1: List of tables and figures

Tables

- Table 1: Planning of master thesis.

Figures

- Figure 1: Purchase decision processes.

- Figure 2: Conceptual model.

- Figure 3: Sustainability of Adidas.

- Figure 4: Sustainability of Nike.

- Figure 5: Sustainability of Nike.

- Figure 6: The usage of social media platform in The Netherlands in 2018.

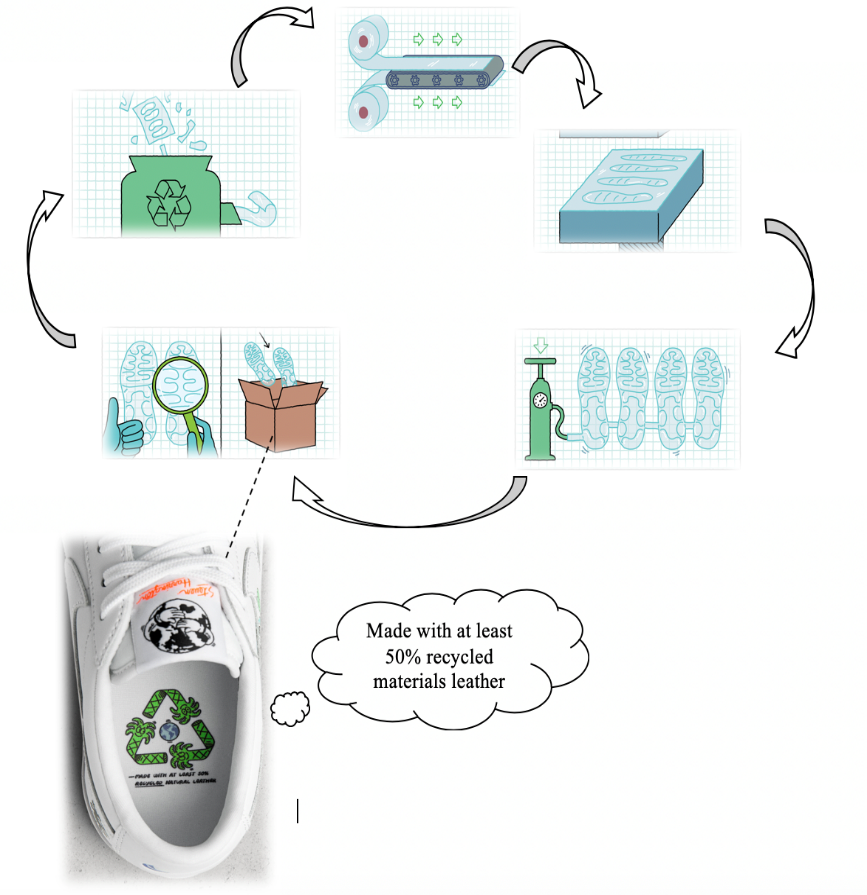

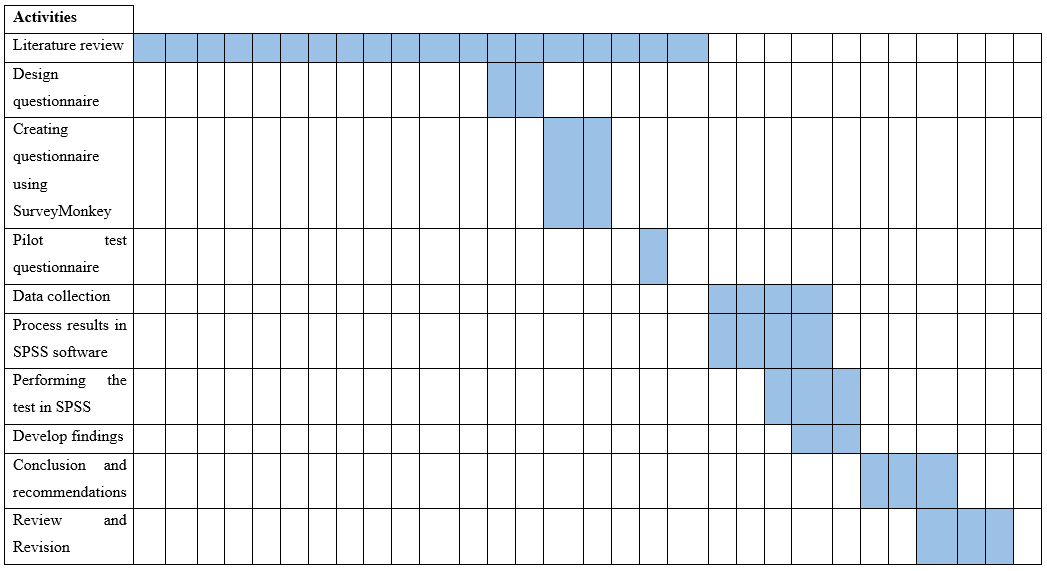

Appendix 2: Initiatives from fashion companies Adidas and Nike

Adidas

Parley x Footwear (Px-F)

In the area of the sustainability plan, Adidas offers various initiatives. Like their cooperation with Parley, which allows Adidas to use recycled ocean plastic and yarn to produce a new product (Px-F). This cooperation makes the company moving forward to become even more sustainable (Amir, 2018). The project aims to improve the environmental impact of the ocean waste that already polluted the ocean, in order to produce the Parley x footwear.

Sustainable product initiative (P-BF)

The initiative intended to use plants rather than oil-based materials in the footwear production process. Plant-Based Footwear (P-BF) already launched to the market in 2018. The first shoe ‘made from things that grow’ that has an upper comprised of organic cotton and a base originating from industrially grown corn, which is a non-food source (Adidas-group, 2019). Adidas started to produce sneakers made from 100% organic cotton, a sole made from a corn-based rubber substitute and an insole made from castor bean oil. 75 % of the shoe is made from biological material. The upper is made entirely of the shoe’s namesake cotton, while the sole is made from a corn-derived bio-based TPU in order to create sustainable footwear.

Nike

Footwear Sustainability Index (FSI)

The focus on sustainability at Nike can be recognized by the (FSI) (Nike, 2019). The (FSI) provides scores based on a variety of relevant environmental criteria and forms the basis for how Nike measure the sustainability of products. The index takes into account the energy, water, and chemicals used to make materials. This index provides a way for Nike’s product creation teams to measure the complete environmental profile of each product and make better choices in developing sustainable products. It is also helping teams understand how to improve the sustainability scores of products through using better materials, such as cotton that is recycled, organic cotton materials that require fewer chemicals or less energy in manufacturing.

Air-Sole Innovation (ASI)

Nike introduced the (ASI) in 1979. Nike is investing in the recycling process since then so waste material can be reused to create value. 75 % of all Nike’s shoes now contain some recycled material (Nike, Annual report , 2018). Recently, the waste material left from Nike’s shoes is being used in tennis courts, athletic tracks, and Nike shoes in order to prevent waste of this material. Furthermore, Nike reuses its shoe materials until they need to be recycled. By reusing these items as much as possible, the company tries to reduce its waste in a way that causes as little damage to the environment as possible (Marc J. Epstein, 2010).

Appendix 3: Planning

Table 1: Planning master thesis.

Appendix 4: Questionnaire

Sustainability practices in the sneakers industry (sports footwear industry)

Dear participant! My name is Rami, currently researching my final project to attain a master degree at Hanze University Groningen – The Netherlands. My research is about the consumers’ perception regarding sustainability practices in the sneakers industry “sports footwear”. The questionnaire will only take 5-8 minutes of your time and your answers will be processed completely anonymously. If you have any questions about the questionnaire, please don’t hesitate to send an e-mail to: [email protected]. I really appreciate your input.

By clicking on the button below, you agree that you belong to the age group 18-35 and that you currently live in The Netherlands

– Agree, start with the questionnaire

– I do not agree, I do not participate in this study

Part 1: General information

- Q1: Which age group do you belong to?

- 18 – 22

- 23 – 29

- 30 – 35

- Other

- Q2: What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

- Q3: What is your nationality?

- Dutch

- Other, namely…

- Q4: How much money do you usually spend on sneakers per month on average?

- Less than €40 per month

- Between €40 and 150 per month

- Between €150 and 200 per month

- More than €200 per month

- Q5: Adidas and Nike are two examples of fashion companies. Do you mainly buy sneakers from these two brands?

- Yes, I buy from Adidas

- Yes, I buy from Nike

- Yes, I buy from both companies

- No, I do not buy from these companies

- Q6: How long do you already shop from these two companies?

- Less than 2 years

- Approximately 2 – 3 years

- Approximately 3 – 4 years

- More than 4 years

- Q7: Would you consider buying sneakers from these two companies?

- Yes

- No

- I already buy sneakers from these companies.

Part 2: Sustainability practices from Adidas and Nike

The following questions are focused on the sustainability lines of the two fashion companies Adidas and Nike. Read the following text about company A (Adidas) and company B (Nike), you will receive a number of questions about this later.

Company A

- In 2015, Adidas has partnered up with Parley for the Oceans which allows the company to use recycled ocean plastic and yarn to produce new product “Parley x Footwear” (Px-F). The project aims to improve the environmental impact of the ocean waste that already polluted the ocean, in order to produce the Px-F.

- Adidas introduced Plant-Based Footwear initiative (P-BF) in 2018. The initiative aimed to intended use plants rather than oil-based materials in footwear production process, ‘the first shoe made from things that grow’ in order to create sustainable footwear.

Company B

- By the end of 2017, Nike’s footwear teams had improved their internal index scores by introducing Footwear Sustainability Index (FSI) allowing the producer to measure the environmental impact of each product. FSI is used to decrease 2.5 % in average carbon footprint per unit. The FSI encourages Nike’s teams to choose better materials to decrease the environmental damage.

- Nike introduced the Air-Sole Innovation (ASI) in 1979 with the aim of minimizing Nike’s impact by using more recycled materials. The company is investing in the recycling process so waste material can be reused to create value. Now, 75 % of all Nike’s shoes contain some recycled material.

Q8 (Controlling question 1): When was company A partnered up with Parley for the Oceans?

- 2014.

- 2015.

- 2016.

Q9 (Controlling question 2): When was the (P-BF) initiative of company A introduced?

- 2016

- 2014

- 2015

Q10 (Controlling question 3): According to company B, the internal index scores (FSI) lead to decrease the average carbon footprint per unit by …

- 3%

- 2.5%

- 3.5%

Q11 (Controlling question 4): When was the (ASI) initiative of company B introduced?

- 1970

- 1979

- 1980

Q12: Answer the following questions using scale 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

To what extent do you agree with the following statements about these two companies?

Q13: Below you see several pictures. To what extent do you agree with the statements about the advertisements of these companies? Using scale 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Advertisement 1

Below you can see two of the sustainability lines of Adidas, in order to create sustainable footwear

Advertisement 2

Below you can see the sustainability line of Nike, in order to measure the environmental impact of each product, also to decrease the carbon footprint per unit

Q 14: To what extent do you agree with the statements about the sustainability practices of Adidas and Nike?

Q15: According to the following scale, to what extent do you agree with the coming statements about the sustainable sneakers from the two companies Adidas and Nike?

Part 3: Reputation, and purchase decision

Q 16: Please rate the reputation from Adidas and Nike from 1 till 5

Q 17: To what extent are you willing to purchase sustainable footwear from the companies Adidas and Nike?

Q 18: How much do you agree with the following statements?

Appendix 5: Usage of social media