Introduction

Today, the US auto industry experiences problems caused by economic decline and financial crisis. Therefore, because innovation is all about creating new realities, change must deal first and last with sight. Many critics admit that the US auto industry will not be able to survive without innovations and new trends in technology as a driver of change. Financial investments are seen as “unrealistic” because of the impaired sight of the state (Daft, 2003). The greatest validation of any change and innovation process is when those involved admit, It is assumed that the strategic intention not only informs all changes in the car industry, but it also adjudicates it, thereby providing almost instantaneous responsive changes–time and place specific. Change presupposes a purpose, an intent; change is continuous creative energy. But change is energy used without specific intent; it is the continuous dissipation of energy.

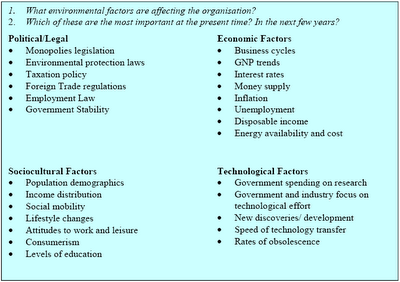

Important Developments in External Environment

The American economy has witnessed fundamental shifts from a production orientation to a consumer orientation, from an economy of scarcity to an economy of abundance, from an agricultural to a mature industrial economy, and from concern about not being able to produce enough goods and services to becoming fully capable of satisfying basic needs through the availability of more than adequate production capacity. In this transition, necessities are now taken for granted, former luxuries become necessities, and expensive, luxurious items, previously unattainable, fall within reach (“Capitalism and the auto crisis” 2008). In such an economic environment, marketing factors become important ingredients of economic growth. In a very real sense, marketing faces a number of increasing challenges in the United States. Although we have developed productive and technical capacities to the point where they are increasingly effective, both outstrip the economy’s marketing capabilities (Ivancevich, 2007).

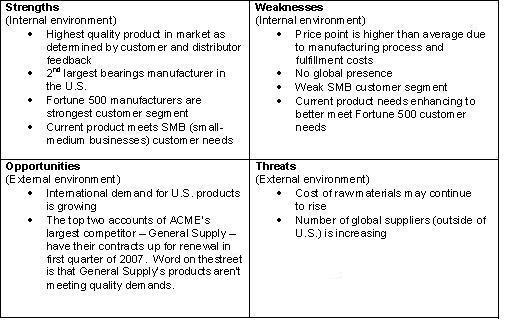

The market-focused economy now challenges society to develop a marketing capacity that will match its physical productive resources. Marketing is a phenomenon of mass systems, reaching its highest form and most efficient development in the creation of mass markets. Mass production can exist only in association with mass distribution, for production does not automatically create its own demand (see appendix 1,2). Automation, for example, is predicted on the belief that mass markets can be created to absorb continuing supplies of products (“Capitalism and the auto crisis” 2008).

Change Strategy of Ford Motor Company

At Ford, organizational change can appear in different shapes, sizes and forms; it can be reflected in various change programs such as total quality management, business process re-engineering, performance management, lean production are being enforced in organizations all over the world. Moreover, each organization has to find its own approach on how to implement change, reduce resistance and achieve higher productivity. As restructuring process in an organization can bring to a variety of issues related to resistance to change and culture breakup or, the opposite, to a high standard performance, it is important to have a detailed management plan, create an appropriate organizational environment to deliver change, follow carefully the steps of change models and focus on human resources.

Organisational Structure

Changes of Organisational Structure of Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company is a leading American car producer with annual sales of about 146.277 billion (2008). In order to complete with Japanese manufacturers, the US industry and Ford Motor Company should introduce innovative technologies based on green technological solutions and energy saving technologies. In such a situation, the mission of car manufacturers will change from profit-making companies to innovators and unique designers. Thus, it will be crucial to introduce changes in every operation and management processes within the system! Anything about the current process and production that cannot be thus transformed must be abandoned. And anything not existing that is needed to complete the production must be created–from within the production itself.

For example, in an auto company, one of the most basic, routine activities is production of car parts; the specifics of the transaction may change from time to time, because of innovation and technological improvements, but it is still production. In actual practice that is the case; the change process seldom reaches to the basic operational aspects of the company. But in whole-context organization, the change is given a new meaning by being cast into a completely new context (Ivancevich, 2007).

Effectiveness of Ford Motor Company’s Change Strategy in Relation to The Organisational Structure

In order to survive in highly competitive world, organizations have to improve their flexibility and be ready to meet change from external environments. He says that changes in organization are often facilitated by such factors as uncertain economic conditions, globalization and fierce competition, the level of government intervention, political interests, scarcity of natural resources, and rapid developments in technology.

As well as increasing demand for high-quality goods, services and customer’s satisfaction, flexibility in organizational structure determines the changing nature of workforce and conflict within the organization (p.909). Therefore, in today’s fast changing business environment, change turns out to be an unavoidable part of social and organizational life.

Organisational Culture

An attempt to rapidly alter or manage culture within the corporation is often a recipe for disaster. Rarely do such attempts provide a sense of security for the employees. This can have a devastating impact on morale. A process of research and interactive collaboration can identify what changes truly need to be made, as well as smoothing the transition toward such changes (Cope, 2000).

Existing Organisational Culture of Ford Motor Company

Certain types of organizational culture are, by their nature, more resistant to change than others. Carter McNamara, a researcher, has identified four distinct culture types. Within each type, variations may exist that limit or enhance the acceptance of cultural change. The Academy Culture typically describes a situation in which employees are highly skilled and remain within the organisation while they advance (McNamara, 1999).

Examples may include colleges, hospitals or large firms. This type of culture is often the most receptive to change, as long as the need for it and the methods of change are well defined. In the Academy culture, employees are given the chance to enhance their skills in a collaborative environment. The collaborative environment fosters trust among the employees and facilitating effective change is made easier. At the same time these employees are highly independent of thought, hence the need for management to provide a convincing argument. Part of that process should involve close collaboration with employees (Hammer and Champy, 1993).

Effectiveness of Change Strategy in Relation to The Organisational Culture

This culture fosters a highly competitive culture. Employees are looking out for their own interest and company loyalty is not an issue. This factor makes cultural change extremely difficult in the Baseball team environment. The structure of the business itself inhibits imposition of any cultural scheme. It is the exception rather than the rule when the rule when this type of culture can be managed to any significant extent. The Club Culture is one in which the central requirement for employees is to conform to the group.

Seniority is valued. Employees start at the bottom and work their way up through the organization. The need to fit in can both help and harm the effort to manage culture. Changes that are dictated from the top have a better chance of acceptance in this type of culture. At the same time, close bonds develop between employees on the same level of the hierarchy to the exclusion of the other levels. That is to say, upper management may not be well connected to the needs and developing culture of those beneath them. Therefore, managing culture in this type of organization is risky but not impossible (Ivancevich and Matteson 2007).

Innovation versus Stability

The study of organizational culture itself can be a valuable tool for management. The information retrieved can be a predictor of the success or failure of larger organizational change. Additionally, it has been shown that a common trait of effective managers at all levels is an intimate familiarity with the corporate culture and the needs of the individual employee. Relationships within the organisation unquestionably affect the company’s ability to provide the final product. In contrast, the lack of focus on human issues has destroyed companies that were otherwise well-managed (Jansen, 2000).

Market Driven versus Technology Driven

Ford is a company that thinks in new cultural terms may be in for a rude awakening. Corporate culture cannot be controlled as the numbers on the balance sheet might be. It develops, in part, because of company actions. However, the human element means that part of the corporate culture will arise independently of anything the company does. The larger the company is, the more difficult it is to manipulate the culture in any meaningful way. The more deeply a negative culture is entrenched, the longer it will take to change it (Levy and Merry1986).

Social versus Economical

This is not to say that the company is completely helpless to its own entrenched culture. A forward-looking, innovative company can accentuate the productive elements of culture and mitigate the negative ones. A careful, inclusive process can create an atmosphere in which corporate culture can be influenced. Shaping a corporate culture in order to achieve a desired effect involves a combination of psychology and management skill. Most importantly, it requires interconnectedness between those managing the culture and the culture itself.

Companies with a history of long-standing, static cultures will have all the more difficulty when trying to change those cultures. Issues of employee trust and feelings of worth can have a large bearing on the acceptance of an effort by management to influence the organisational culture. From there, continual consultation and evaluation with the employees can foster an atmosphere of trust. All aspects of organizational culture cannot be “managed.” Inevitably, the interaction of human beings will create cultural elements separate from what management strives for. However, management can provide leadership and create an atmosphere in which a productive culture can emerge (Podlesnik and Chase 2006).

Organisational Politics

Each area task force consisted of the area manager (task force leader), one or two department managers, two or three supervisors (with leadership functions), and a number of employees equal to the total number of managers on the task force. In addition, each task force was assisted by two facilitators: one member of the company’s personnel office and one of the consultants. While management representatives were chosen by the chief executive, the employees selected their own representatives to serve on their task force.

Employee selection followed a presentation of the project at a corporate area meeting with all employees. Improvement in the quality of work, the original goal of the organizational assessment, was addressed starting in mid-1990 by establishing quality circles. The project detour, however, points to the importance of employee involvement and the improvement of the quality of working life as a precondition for achieving other organizational goals. Employee commitment to new organizational goals is unlikely unless their own concerns and interests are seen as central to organizational change (Ford Motor Company 2009).

Change Strategy in Relation to Organisational Politics

The innovation process starts with an idea and ends with the actual implementation and utilization of a piece of new machinery, for example. Information has to be collected and communicated, employees may have to be trained, departments may have to be reorganized. Every innovation has an impact on those directly and indirectly affected by it. Jobs can change or be lost, or new jobs may be created.

New technologies may help eliminate certain problems but may create many others. Such planned or ongoing organizational innovations can be utilized by applying the judo principle, that is, using the forces already at work for the purpose of enhancing competence development through participation. To achieve this, the “typical” approach to planning and implementing technological and organizational innovations in a given organization needs to be explored. The analysis of the innovation process itself provides an opportunity for employee participation and yields information about where and how possibilities for competence development can be strengthened. It also identifies the weaknesses in organizational innovation processes where worker participation may lead to better outcomes (Armstrong 1006 p.346).

Both types of change can be opposed by individual and by organization itself, which may cause a failure. As Sherman and Garland 2007() points out, the better the technological or organizational innovation is understood — the more is known about its goals, the actual innovation process, and all those participating in it — the easier it becomes to identify opportunities for influence. For each innovation a better alternative may exist. There is no one right way to plan and implement an innovation process. The following overview describes what questions to ask, and how asking the right questions about technological and organizational innovations, the innovation process itself, and the innovation participants can identify alternatives and opportunities to influence the process as well as the outcomes. Whereas Mullins (2007) gives reasons of organizational resistance emphasizing such weak areas as culture, maintaining stability and predictability, investment in resources (as extra expenditures), past contracts and arrangements (with government, trade unions, other companies or customers) , threats to the power and influence of certain groups within the organization.

Effectiveness of Change Strategy

By comparing alternatives the bottom-line advantages and disadvantages of different options can be explored. Considering alternatives is also important because it often shows that planning for innovation has been done very superficially, with little consideration of the variety of possible impacts. This analysis is likely to expose the underlying purpose of a proposed innovation. Robots are sometimes introduced with the argument that they eliminate the health and safety hazards of certain jobs. These goals might be reached in other ways, however, without the job reductions that often accompany the introduction of robots. Talk to the people in charge of planning the innovation, and talk to other people in the organization who are knowledgeable about the subject but are not involved in the planning. Consult experts from labor unions, universities, and other institutions (Ivancevich, 2007; (Levy and Merry, 1986).

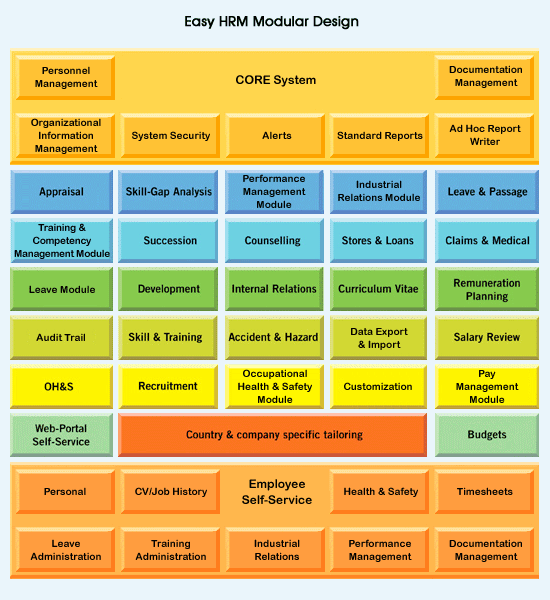

Human Resource

In spite of these very legitimate concerns, Ford often lacks a coordinated strategy to get supervisors actively involved in the change process. Instead, it is assumed that resistance to change is normal and is likely to disappear over time. It has been argued throughout this book that, in order for work reorganization projects to be successful, the employees affected have to be involved in the design and implementation of the change process; If these elements are included in a broader change strategy, the frequent assumption that a gain for the workers must mean a loss for supervisors becomes unjustified. Work redesign is not a zero-sum game.

The benefits for one group need not be to the detriment of another group. This is evident if we contrast the role of supervisors in group-based work organization based on socio-technical systems principles with their role in a traditional systemIn a traditional work system the supervisor is expected to control the task execution for each individual job, particularly if the jobs and work tasks are linked so that the scope of activities and decision latitude of individual workers are very limited. Detailed job descriptions and task instructions support the execution of the supervisory function. Instead of direct instruction and control, supervisors play a mediator or facilitator role in helping the work group solve production problems or conflicts within the group. They provide constructive (learning-oriented) feedback about deviations from production goals and objectives. This leadership role involves assisting the group in defining their primary work activity and in setting realistic goals in the context of existing resources and constraints.

Recommendations For Change Strategy

Effective organizational functioning requires that organizational stakeholder interests be optimally balanced. The main stakeholders in the modern enterprise may encompass customers, employees/union, management, shareholders, suppliers and other business partners, and the public at large. In some areas the interests of these stakeholders overlap; in other areas they may conflict. For example, union/employee concerns about fair, increasing wages may be in conflict with management efforts to cut costs. Or a company’s neglect of environmental protection regulations may save money in the short run, but may negatively affect workers’ health or the broader public if spills or soil or water pollution accidents occur.On the other hand, there are many areas of overlapping interests. Employee skill and competence enhancement, for example, may require the reallocation of resources and thus represent a cost in the short run, but may benefit customers, employees, management, and shareholders in the long run if it results in employee job satisfaction, improved quality, and reduction of waste and thus contributes to organizational competitiveness (Ford Motor Company 2009).

It may be useful for management and union/employee representatives to do their own independent assessment of overlapping and conflicting interests first and then use their different analyses as the basis for discussion and negotiation on how a competence development process can optimize mutual interests (Senior, 2001). In the new manufacturing environment several factors combine to create new imperatives for compensation policy. The new management strategies based on JIT and TQM have resulted in a reconceptualization of productivity and a rethinking of the relationship between productivity and quality. The new social relations of production emphasize group problem-solving with a serious attempt to extend worker concerns beyond the context of their immediate job and to tap the knowledge and creativity of workers in addressing broad organizational concerns.

In the case of autonomous work groups–or what the authors of this book call work design for competence development–jobs may be broadened, technology reorganized, and responsibility and accountability internalized within the group. The new technology involves automated systems that are potentially both more highly integrated and more flexible. Computer systems that are vastly more powerful, more user friendly, more easily integrated, and less costly will result in the introduction of automated systems in lower volume, less standardized environments.

Change Strategy in Relation to Organisational Structure

Employees are encouraged to list all the problems that concern them now or that have bothered them for a while. The focus of the problem collection is on the daily hassles people have to contend with. Competitive pressures from more advanced countries and more advanced organizations and the dynamics of the customer-supplier relationship will eventually force most companies to adopt part or all of these changes.

The focus of change (management strategies, social relations of production or technology) and the rate of change will vary from organization to organization and from industry to industry depending on position within the international economy, basic technology (process, mass production, batch production, etc.), and a host of other factors. The new practices will focus more and more attention on production costs, quality, and rapid response to changing markets. As the new production system becomes entrenched, interest in new and more compatible systems of compensation will grow (“Capitalism and the auto crisis” 2008).

Both the meaning of productivity and the means of attaining higher productivity levels change in the context of just-in-time manufacturing and total quality management. Under Taylorism the main focus of productivity enhancing efforts is direct labor, and the main approach is micro analysis of individual direct labor jobs. Industrial engineers simplify by breaking jobs down into elements or even micro motions, eliminating unnecessary motions, resequencing for efficiency, and redesigning the layout, tools, and even product, all with the goal of minimizing the amount of necessary direct labor time for the operation. As simplification progresses, the complexity of remaining tasks is reduced, and it becomes easier and easier to imagine mechanized or automated systems capable of performing the operation (Senior, 2001).

Change Strategy in Relation to Human Resources

Both purchasing situations and the decentralization of authority affect pricing policies at Ford Motor Company. Prices may vary by the quantity purchased, and the purchaser’s geographic area, trade position, and the functions he performs, as well as by the method and timing of purchases. In large, decentralized companies featuring profit-center accounting, intra-company pricing and transfer pricing, (prices charged by one company unit to another) can influence product prices and raise significant conflicting problems (Ivancevich, 2007).

Obviously, regardless of economic models, it is difficult to establish an optimum price because demand and costs change over time. The attention usually settles on current profit maximization rather than on the long-run maximization; the whole life cycle of a product and the total product line, rather than a single item, must be considered in pricing; and price must be considered from the perspective of the total marketing mix. The concept of price or demand elasticity refers to the sensitivity of buyers to price changes. When small variations in price bring about relatively large variations in buyer reaction, the price elasticity is high. The situation is reversed for low elasticity. Since various customers react differently to price changes, knowledge of demand elasticity helps to set prices. But the major problem is that detailed data are not available (Senior, 2001). Yet, several techniques can be used to approximate elasticity, including market tests, statistical techniques of historical or cross-sectional analysis, and surveys (“Capitalism and the auto crisis” 2008).

Change Strategy in Relation to Organisational Politics

The operating principle is to anticipate problems and solve them in advance, before they have the opportunity to disrupt. This is the principle that instructs preventive maintenance, setup reduction, and statistical process control programs. All of this works better when workers are involved and committed to making the system work. One way of looking at quality circles, team concept models, and semi-autonomous work groups is as a form of “preventive” labor relations designed to anticipate and solve human problems before they are transformed into production problems (Schien, 2000, see appendix 3).

Construct a dialogue concerning desired futures

A process must be invented that allows people to coordinate their individual perceptions of contradictions and problems in order to construct a shared vision. This can occur through the dialectic of collectively reflecting on problems, taking action to implement improvements, and then reflecting again on the effectiveness of the changes. The need to create a mechanism for an ongoing dialogue is central to the processes of both individual competence development and social system change.

Build a “good dialectic” through open information and communication

Information and communication are key ingredients in constructing a dialogue in which employees can invent alternatives and develop new goals. Most organizations make little effort to communicate their goals, the challenges they face, and their strategies for addressing them all the way down to the shop floor or the “front line” of their operation. The manufacturing worker who has never been informed about where the part that he or she produces goes is not a rare exception. The more employees know about the “bigger picture” and how their work fits into it, the more aligned their creativity becomes with future work demands. Yet communication has to be a two-way process. Communication not only has to flow top-down, involving more than newsletters and piles of memos, it also has to flow bottom-up. Through direct, verbal, two-way communication a dialectical process of mutual learning and dialogue can be initiated. The most valuable information often comes from employees’ experience. Such information is generated if employees are given the opportunity to experience and link aspects of work activities that they did not perceive before or saw as unrelated.

Competence develops through engagement in new activities

The process of competence development begins with direct participation in new activities. These new activities expand the range and scope of task demands and response possibilities. The critical exploration of existing work arrangements, in relation to both organizational and individual goals, reveals contradictions and problems between how things are and how they could be. This kind of “gap analysis” lays the foundation for inventing alternative possibilities. Envisioning and implementing changes in current work activities and arrangements allow for continuous adaptation and reassessment, help identify additional training and skill requirements, and foster the development of new goals and employee interest in taking on new challenges.

Start with contradictions

Most employees are aware of many problems and contradictions that interfere with optimal job performance in line with their own goals and those of the organization. But many of them have never been asked about their perception and ideas or, if they volunteered them anyway, quickly found out that nobody cared. First and foremost, employees have to realize and to be able to believe that work activities can be changed. Contradictions between the reality of their work situation and their subjective goals, even if recognized, do not automatically result in change-oriented action as long as the situation is defined as “resistant to change.” The willingness to change and think about alternatives grows with a heightened awareness of contradictions in existing work arrangements if the situation is perceived as open to change and if the changes proposed seem desirable and feasible (Mullins, 2007).

Change Strategy in Relation to Organisational Culture

After the desired changes have been successfully implemented, they have to be consolidated, and the process has to be firmly integrated in the organizational culture. Subsequent innovations should be utilized to develop new project teams. Participation structures and processes should be integrated and defined in written agreements (e.g., labor contracts). The goal is to make employee participation not just a one-time project, but a part of organizational culture and employees’ everyday work activities. Involving employees in innovation processes presents two basic difficulties (Mullins, 2007).

The first problem is to demonstrate to employees that they stand to benefit from cooperating in the process. The prospect of participation in planning and decision-making may arouse fears and possibly resistance among employees new to this process, based on their previous experience that workplace changes are frequently accompanied by deskilling and the elimination of jobs. They know that too often they bear the negative consequences of “work improvement” projects. In addition, many employees have found that management has failed to act on their input and suggestions for improvements in the past. These types of experiences do not provide positive reinforcement for continuing to participate. Some barriers emerge from the concern that employee participation may eliminate the privileges of some groups in the organization.

Many supervisors fear the loss of control and decision-making power. They are worried that employee participation means less decision-making latitude and influence for them. Employee participation is intended to open up new domains of responsibility and decision-making for supervisors as they are freed, for example, from certain tasks that the work group can take on. Other obstacles are related to the discomfort of having to give up cherished old habits. New aspects of culture should bleed into every activity of the corporation. They are intangible qualities, but they should be significant none the less. Management of the corporate culture requires recognition of what can and can not be changed. The manager must go one step further and ask why the change should be made and how people will react to it (Mullins, 2007).

Conclusion

In sum, in Ford Company there is a critical need to address radical change, personal inconvenience, and new accountability. The new production system is spreading rapidly due to powerful competitive pressures. It provides companies with a new approach to improving productivity, controlling costs, and enhancing profitability. Unions typically have been exposed to this system piecemeal and have had difficulty understanding the relationship between the various components of the system. Its internal logic, goals, and potential impact have also remained obscure. This lack of clarity about the underlying production system and its relationship to compensation practices has meant that existing pay practices have been difficult to change and new practices have been difficult to design and implement effectively.

Bibliography

CAPITALISM AND THE AUTO CRISIS. 2008. Web.

Cope, Mick. 2000, Know Your Value. Publisher: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

Daft, R. L. 2003. Organizational Theory and Design. 9th Edition. South-Western College Pub; 8 edition.

FORD Motor Company. 2009. Web.

Hammer, M, Champy, J, 1993, Re-engineering the Corporation. Nicholas Brearley, London.

Ivancevich Michael T. Matteson John M. 2007. Organizational Change, Ashford University.

Jansen, K. J. 2000, The Emerging Dynamics of Change: Resistance, Readiness, and Momentum. Human Resource Planning, 23 (2), 53-55.

Levy, A., Merry, U. 1986. Organizational Transformation: Approaches, Strategies, Theories. Praeger Publishers.

Mullins, L.J. 2007. Management and Organizational Behaviour. 3 d Edition. Pitman Publishing.

Podlesnik, CH., CHASE, PH. N. 2006, Sensitivity and Strength: Effects of Instructions on Resistance to Change. The Psychological Record, 56, (1): 303.

Senior, Barbara. 2001. Organizational Change, Capstone Publishing.

Schien, E. H. 2000. Organizational Culture and Leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Sherman, W. S., Garland, G. E. 2007, Where to Bury the Survivors? Exploring Possible Ex Post Effects of Resistance to Change. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 72, (1); 52.

Appendix