Abstract

This pilot study is conducted as part of a minor thesis in the Master of Information Systems.

It aims to explore the use of social networking sites (SNSs) by Saudi female students in Australia, with particular emphasis on Facebook. Using the appropriation technology model, the study also aims to uncover the factors associated with and influencing their attitude towards using SNS and whether the experience of studying in Australian institutions may influence the students’ perception towards and use of SNSs.

To report the perceptions of these females about their experiences on SNSs in general and Facebook in particular, the authors conducted five semi-structured in-depth interviews with international Saudi female students in Melbourne. The study found that the majority of these females started using Facebook after they came to Australia. However, most of them heard about the site from friends or media but not from their education providers. Despite that, all the students showed a positive attitude and an increased willingness to use the site as part of their education experience.

Currently, the majority used Facebook mainly to keep in touch with their friends and family irrespective of their geographical boundaries; to gain knowledge on the various social and political events that happened around them, and to have fun through posting photos and comments. Interestingly, while the respondents reported their trust and awareness of Facebook privacy and apply them to their profile identity information, they appeared to be conscious about the privacy of their photos. These concerns resulted in the students’ unwillingness to post any personal photos which may result in undesirable social consequences such as damaging their family reputation.

In terms of the effects of their Facebook experience on their lives, the students consider the advantages Facebook gave them are more than the disadvantages. The majority of the participants said Facebook strengthens their relationship with their friends and family made them more sociable and more self-confident, others expressed concerns about the time Facebook took away from practicing more productive activities such as their hobbies, family and study.

Introduction

Research Background

In today’s highly competitive and knowledge-driven economy, education, and in particular higher education plays a vital role in the overall growth of the economy. Over the past few years, higher education in Australia has experienced rapid growth in the number of international students; including those from Saudi Arabia (Australian Education International, 2011). In 2011, a report by Australian Education International (2011) ranks Saudi Arabia among the top ten key sources of international students in Australia for the first time (Australian Education International, 2011). Of all the Saudi students in Australia, there are over 1,517 Saudi female students whose numbers are expected to increase due to the recent extension of King Abdullah’s scholarship program (Ministry of Higher Education, 2010 as cited by Alhazmi, 2010).

In contrast to other international female students in Australia, it could be argued that international Saudi female students are being faced with different challenges during their study period in Australia. Therefore, Australian instructors must understand these challenges to be able to meet the needs of this particular student demographic.

Among the various challenges encountered (eg linguistics difficulties), the transition from a highly segregated educational environment to a mixed class environment can be considered as one of the most influential challenges which have adversely affected their academic achievements due to the difficulty to communicate with the opposite gender (Alhazmi and Nyland, 2011). In the Saudi culture, women are not allowed to mix or communicate with unrelated men in areas such as education, public transport, and the workplace (Al-Saggaf, 2004).

In addition to the cultural and social challenges, Shaw (2009) points out another major challenge experienced by the international Saudi students that need to be examined, which is the transition to a completely new educational environment that greatly differs from their home country’s educational environment. By studying in Australia, International Saudi students moved from a text-based and exam education system in Saudi Arabia (Oshan, 2007) to a research and web-based education system wherein technologies such as wikis, blogs, and social networking sites (SNSs) have been integrated into most of the universities learning management systems (Kennedy & Judd, 2010).

In contrast to Australian universities wherein Web 2.0 technologies are incorporated into the classrooms to provide students with a high-quality educational experience through the creation of an effective collaborative environment to share and develop their ideas (Gray et al., 2010), only recently has Internet access become available to students in Saudi universities. Consequently, it would be difficult to expect current Saudi students to be savvy users of various information and communication technologies and thus be able to apply these technologies in learning settings (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010).

Additionally, findings from various studies; Kennedy et al. (2007); Gray et al. (2010) which examined the use of various web 2.0 technologies such as SNSs by college students showed that students from different countries, both developed and developing ones; from different cultures such as collectivist vs. individualist; or even students from the same country may have different perceptions and experiences on the same set of technologies due to demographic factors. Therefore, different cultural backgrounds of students should be considered when using technology in any educational context as individual backgrounds may influence the student’s personal experience with the intended technology (Gray et al., 2010).

In the context of international female Saudi students, these students belong to one of the most conservative cultures in the middle-east (Al-Saggaf, 2011), which greatly influences their tendency to adopt online communication technologies (Oshan, 2007). In Saudi society, online communication tools are means of facilitating the prohibited connection between women and men, and thus some Saudi families restrict their daughter’s Internet use and freedom in an attempt to protect their reputation, which is taken very seriously in the Saudi culture (Oshan, 2007). Consequently, females largely show more anxiety before joining an online communication site than males (Oshan, 2007).

The presumption of this research, however, is that the unique opportunity presented to international Saudi students studying in Australian universities, which are well regarded for their technology, gives them immediate exposure to the internet and its applications and allows them to exploit the benefits which web-based technologies (e.g wikis, blogs or even SNSs) can provide to enhance their learning.

It also helps them overcome some of the social, technical (connectivity and accessibility), and cultural (family restrictions and pressure) barriers identified by their counterparts in Saudi Arabia (Oshan, 2007). Moreover, it increases the Saudi women’s need to use online communication technologies which would help them to keep in touch with their remote friends and family. Consequently, it is believed that these students will use and adopt Web 2.0 technologies more than their counterparts in Saudi Arabia.

Why Facebook (FB)

Of the various Web 2.0 technologies (e.g. wikis, blogs, social bookmarking), social networking sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and MySpace have increasingly attracted millions of users worldwide, and have been integrated into their daily practices (Ellison et al., 2007). Facebook (FB) in particular has established a huge base of users mainly among college/university students not only in developed countries (Jones, 2004; Jones & Soltren, 2005; Lamp et al., 2006; Young & Quan-Haase, 2009) but even in conservative countries such as Saudi Arabia (Al-Saggaf, 2011; Al-Otaibi, 2011).

Its popularity, aside from being an easy-access online portal, is because of its potential for professional, educational or personal purposes (i.e., online business meetings, enhance the learning experience, provide a collaborative environment for teaching, contact loved ones abroad, etc.) (Alexander, 2006). It has been argued that women are more likely to make use of SNSs than their male counterparts as these sites have the potential to fulfill their interpersonal and expressive communication style (Tufekci & Spence, n.d.; Hargittai, 2007).

However, Al-shadadi’s (2009) study showed that the population of women participants on FB in Saudi Arabia was only 38% of the total number of the 231 thousand subscribers. Despite the low uptake, however, the researcher found the presence of Saudi women on FB is much higher than on other SNS or online forums, which is why FB has been chosen as the SNS for this study. Another reason to focus on FB is the outstanding popularity of FB among college students population and the sample of our study (i.e. Saudi women students) belonging to that population (Jones, 2004; Jones & Soltren, 2005; Lamp et al., 2006; Young & Quan-Haase, 2009).

Additionally, in Saudi Arabia wherein the freedom of expression is limited, FB can provide Saudi women with a safe avenue to make their voices be heard and discuss their problems and concerns (Al-Saggaf, 2011), as well as to express their feelings without the need to use their real names (Al-shadadi’s 2009 as cited in Shaheen, 2010).

Research Problem

To date, many studies have examined the use of Web 2.0 technologies in general and SNSs in particular by college students from different cultural backgrounds. However, most if not all are conducted on students from developed countries such as the US, UK (Lampe, Ellison et al., 2006; Lampe, Ellison et al., 2007; Shade, 2008; Pempek, Yermolayeva et al., 2009; Young, 2009) or on international students (Gray et al., 2010) other than international Saudi women. Consequently, due to the lack of studies conducted on Saudi female’s use of and attitude towards SNSs, it would be difficult for educators in Australian universities to understand the reasons behind their resistance or acceptance of the specific technology which would affect their effective utilization of these technologies for their learning experience.

To the best knowledge of the researcher, there has been no published research focused on the experience of international Saudi female students in Australia in general and on their use of SNSs in particular. However, there are a few studies (Table1) focused on the experience of international Saudi students in Australia. Most of the studies examined the various cultural and social adjustment issues which adversely affect the Saudi students’ educational experience in Australia.

Table 1: Research on International Saudi students in Australia.

Therefore, the current study aims to contribute to the literature through the empirical examination of the use of SNSs by Saudi female university students in Australia – with a particular focus on FB. It will also examine the motives among Saudi women for using FB and whether their uses in Australia differ from those in Saudi Arabia.

Research Questions

The current research aims to answer the following questions:

- Why do International Saudi women students use Facebook?

- This question aims to discover the factors that may encourage or discourage Saudi students to use FB.

- How do international Saudi women students use Facebook?

- This question attempts to discover the students’ main uses and their information revelation behavior such as the amount and accuracy of information included in their profiles. It also aims to assess the students’ awareness of the potential of Facebook for their educational experience as well as to compare their use of Facebook when they were in Saudi and Australia to discover if there are factors that lead to changes in their use.

Research Objectives

The main objectives of this research are:

- To identify the motivators to use Facebook and whether they encounter any barriers when they use them and, if so, what those barriers are.

- To determine students’ general patterns of use and whether their uses in Australia differ from those in Saudi.

- To assess the students’ awareness of the potential of SNSs for their academic achievements.

- To explore female students’ positive and negative experiences in the use of social networking sites.

- To identify factors associated with and influencing female use of and attitude toward the use of these sites.

Theoretical Model

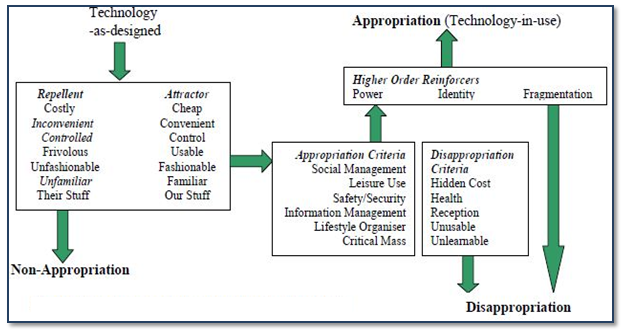

The study employs a Technology Appropriation Model (Carroll et al., 2001) as the theoretical lens to examine the use of SNSs by Saudi women. The model is chosen because it provides the means to describe and explain the appropriation process through which SNSs are transformed from being a technology as designed to a technology that meets the Saudi female students’ needs and thus contributes to the integration of SNSs in their daily practices.

By using the proposed model, we would be able to answer the research questions by identifying three sets of factors that explain why the students adopt SNSs (i.e, attractors), how Saudi women adapt and shape it to meet their needs (appropriation criteria) and whether the technology is adapted and integrated (reinforces) into the students’ everyday lives (appropriation) or they decide not to use it (disappropriation) (Carroll, Howard, et al. 2001).

Significance of Research

The findings of this research will contribute to the literature on social media in Saudi Arabia, as being the first study to examine the use of SNS by non-resident Saudi students. The study will also contribute to the international students’ literature; as the study will be conducted on a group of students who belong to the international students’ population in Australia.

Moreover, with the increasing number of scholarship Saudi students studying in Australian universities, it is believed that the findings of this study will help Australian educators understand important issues in Saudi female students’ SNS use and attitude, which may affect the students’ effective utilization of these technologies for their academic achievements.

The current study would contribute to the social networking sites literature as being the first study to examine the use of FB by applying the lenses of the technology appropriation model (Carroll et al., 2001) to come up with the conclusion as to whether Saudi women consider FB as an appropriate technology or not. In the SNSs literature, many studies were conducted using the Gratifications and Use theory and were focused on examining the motives to use FB (Joinson, 2008; Pempek et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Al-Otaibi, 2011; Raacke & Bonds-Raacke, 2008).

The paper presents an exploratory study that will provide baseline data for future studies in the field, recommendations, and suggestions to encourage Saudi female students, regardless of their location, to the effective use of SNSs for the empowerment of their social, academic, and professional lives.

The Paper Outline

The thesis comprises of six chapters.

- Chapter 1 presents the background of the topic, research objectives, and its significance.

- Chapter 2 discusses the literature review relating to the research objectives.

- Chapter 3 is the methodology section describing and justifying the research approach and methods.

- Chapter 4 examines the findings of the study.

- Chapter 5 discusses the results, closes with the conclusion and recommendation, and highlights some important ideas for further exploration of issues that could not to be covered in this thesis.

Literature Review

This chapter will present an overview of the current research conducted on the usage of social networking sites (SNSs), with a focus on its usage in Saudi Arabia. The literature review will present a comparison of the findings between the studies conducted on Saudi students and the other studies in SNS literature with regard to trends in usage of Facebook among students, motivators, privacy and trust issues, and positive and negative impacts of Facebook use. Finally, a brief description will be given of the proposed theoretical model used in the current study.

SNS Literature Overview

To date, an enormous body of research has examined the use of SNSs such as Facebook by university students (Lampe, Ellison et al., 2006; Lampe, Ellison et al., 2007; Shade, 2008; Pempek, Yermolayeva et al., 2009; Young, 2009). Themes such as: the uses and gratifications of SNSs (Joinson, 2008; Pempek et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Raacke & Bonds-Raacke, 2008), their role in building and maintenance of social capital (e.g., Ellison, Steinfeld & Lampe, 2007), their role in the political and civic engagement (Valenzuela et al., 2009) concerns about privacy (Gross & Aquisite, 2006; Young & Hasse, 2009) and gender differences in the use of SNSs (Muscanell & Guadagno, 2012) were examined.

However, much of the data is limited to university students in developed countries such as the US and Australia; thus they do not reflect the population from developing countries due to the various social, technical and cultural differences between the two worlds that influence the students’ personal experience with the technology (Gray et al., 2010).

SNS Research on Saudi Students

In the context of Saudi Arabia and social networking sites, till now there have only been limited studies (Table 2) conducted to investigate the usage of Facebook by Saudi students especially by the female Saudi students. The lack of studies on the use of SNSs by Saudi students can be attributed to the fact that SNSs is a recent phenomenon and their introduction in Saudi Arabia was met with a fear that online communities could destroy Saudi family values and social traditions (Al-Otaibi, 2011).

Table 2: Previous Research Conducted on Saudi students’ Usage of Facebook.

As seen in the table above, the only research to examine Saudi female students’ use of SNSs was on Saudi females studying in Saudi Arabia. The only published study relating to Saudi female students’ use of Facebook was an ethnographic study conducted by Al-Saggaf (2011) conducted in 2009 and published in 2011. It examined the use of Facebook by 15 young female Saudi students at a private Saudi university.

Another study was a conference paper written by Aljasir et al. (2012) which examined the reasons why Saudi college students do not use Facebook. The third was a master dissertation written in Arabic by Al-Otaibi (2011), who examined the use of Facebook by Saudi students at three public universities in Saudi Arabia. The last study was a working paper presented by Alshadadi (2009) at a seminar in Saudi Arabia on “Issues of Saudi women on Facebook” (as cited in Shaheen, 2010), but this researcher did not have access to this paper. Both Al-Otaibi’s (2011) and Alshadadi’s (2009) studies have gained the Saudi media attention as being the first studies to examine the use of Facebook by Saudi students.

A review of Al-Saggaf’s article showed that despite the assumptions of divergent motivations between different cultural settings as to social networks’ use, the experience of young Saudi females and Facebook usage show far more similarities with their young adult counterparts in the West (Al-Saggaf, 2011). Al-Otaibi’s (2011) findings, however, showed the opposite. This literature review will focus on comparing different findings between the studies conducted on Saudi students and the other studies in SNS literature.

A Comparison Between Trends in Facebook Usage Among Saudi Students and Other Students

SNSs Experiences: Time commitment difference

In Saudi, Alotaibi (2011) found that more than (77%) of the students use Facebook, with the majority (74.4%) using it every day. However, in contrast to Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007 Pempek at al., 2009, Saudi students seem to spend much more time, between 1 to 5 hours every day, than their western counterparts who use Facebook on an average of 10 to 30 minutes. In Pempek et al.’s (2009) study, the students spend approximately 30 minutes on FB throughout the day.

Much of this time is spent on lurking rather than updating or posting content. One explanation for the difference in the time spent on Facebook between Saudi and US students could be the lack of outside leisure activities provided to Saudis which may lead them to spend more time staying at home and thus Facebook can help them to pass their free time (Oshan, 2007). However, the amount of time spent on FB varies with demographic factors such as age (Lampe et al., 2006) and marital status (Al-Otaibi, 2011), with younger students and married couples using it for more time than older and single students. In Saudi culture, married people have more free time than the singles (Al-Otaibi, 2011).

This study will add to the literature by examining how much time Saudi female students in Australia commit to Facebook. Do they compare with their counterparts in Saudi Arabia or are they like Western students? Does the amount of time dedicated to FB vary with age and marital status of the students?

Motivators

Previous studies have identified several reasons that motivate Saudi students to use Facebook. Table 3 shows the motives Saudi students identified as reported by Al-Saggaf and Al-Otaibi:

Table 3: Motivations of Facebook usage among Saudi students.

Al-Saggaf (2011) found that the majority of his participants use FB mainly to keep in touch with old and existing friends, to find out about these friends (i.e. surveillance function) referred by Lampe et al. (2006) as ‘social searching’ which helps these users to gain emotional support and fellowship. Similar findings are documented by Boyd & Ellison (2007), Jones et al. (2008), Valenzuela et al. (2009), Young (2009), and Shade (2008) in western studies.

While contacts and communication have been found as the common motive to use FB, Saudi students identified it as the third motivator in Al-Otaibi’s research, with more males than females choosing the motive. This is attributed to the cultural and social constraints put on females. In Saudi culture, women are always expected to remain modest, respectful, and seldom engage in social interactions with men (Oshan, 2007). Therefore, maintaining contact and communication with others would not be a priority for Saudi women.

Linked with communication, Al-Saggaf (2011) pointed out that indirect peer pressure, curiosity, and the need to pay attention to friends’ requests to join FB are instrumental in motivating the students to use FB. Curiosity as a motivator leads to “lurking,” or observing others’ actions—such as reading the news feed about what friends are doing or looking at others’ profiles or pictures. Lurking was far more common than posting information or even updating profiles (Pempek et al., 2009), and was reported by Al-Otaibi’s participants as one of the main motivations to use Facebook.

Additionally, the Facebook Groups feature was among the services that motivate Saudi female students to use the site in which they can freely express their diverse political ideas (Al-Saggaf, 2011). This finding contradicts what has been found in the literature in which western students reported rare participation rates in their groups (Pempek et al. (2009) and that they just joined groups as a way of enhancing the appeal of their profiles and increasing social networks rather than making a social statement or leaving an effective difference in the world (Shade, 2008).

The research on motives for Saudi students to join FB reveals the main difference between Saudi use and western use of the site was Al-Otaibi’s (2011) findings that indicated that entertainment is the main motive. This finding contradicts Young’s (2009) results in which “entertainment” was described as a “less important” reason to use Facebook as reported by her western participants.

Finally, gaining knowledge was identified as the last reason to use the site (Al-Otaibi, 2011). However, it has been found that Saudi students acknowledged the educational potential of FB as it can be used as a source of seeking and receiving information that would help them to increase their knowledge and improve their study achievements.

This study will add to the literature by examining the major factors that draw Saudi female students in Australia to Facebook. Given that this group of Saudi students is different from those studying in Saudi Arabia (in terms of distance from their families and easy access to the technologies), it would be interesting to find out what factors motivate their use of FB and whether these factors are any different (or have different priorities) from those identified by Saudi students living and studying in their home country.

In addition, besides looking at the motivators, this study will also look at the barriers to using Facebook by Saudi female students. Indeed, this area has only been studied by Aljasir et al. (2012) who sought to find out why some Saudi college students do not use FB. He found that preference for other modes of communication, lack of interest, lack of time, and lack of access to a computer were the major reasons for not using FB. The study’s participants were students studying in Saudi Arabia. This study will identify the barriers that are specific to Saudi female students in Australia and will identify any similarities or differences in the barriers mentioned by Aljasir et al. (2012).

Privacy and Trust Issues for Facebook users

Despite the high level of trust in Facebook (Dwyer et al., 2007), female Saudi students showed greater concern and anxiety when it comes to privacy regarding personal photos and profile identity due to cultural implications (Al-Saggaf, 2011). Consequently, Saudi female students, who reported posting personal photos and self-disclosure, made their profile more private and to be accessed and viewed only by their friends who they trust and know that they would maintain their privacy (Al-Saggaf, 2011).

Posting Photos

While Tufekci and Spence (n.d.), Shade (2008), and Pempek et al. (2009) found that posting photos was a major activity performed by college students, Saudi females considered photos among their private information and treated them with greater privacy concerns (Al-Saggaf, 2011). Saudi women were aware of the danger of displaying their photos which, if they fall on the wrong hands, could result in serious damage to their family reputation. Even with Western women who may have more freedom to post their photos, tagging photos without their permission was among the negative experiences they had faced. However, the reasons they gave to their dislike of this feature was their appearances (i.e., they do not appear in a good way) rather than a cultural reason as identified by Saudi women.

Profile Identity

While the vast majority of Facebook users seem to provide their fully identifiable names (Gross & Aquisti, 2005), 54.5% of Saudi students – male and female – use pseudonyms (Al-Otaibi, 2011). It can be argued that based on the main motivator to use Facebook is keeping in touch with friends, revealing more personal and accurate information such as real name is understood (Joinson, 2008). The Saudi students in Al-Otaibi’s study use Facebook mainly for entertainment and time passing purposes and thus were more likely to use fake names to protect themselves or have fun (Young & Quan-Haase, 2009).

In Saudi Arabia where freedom of expression is limited and gender communication is prohibited (Al-Saggaf, 2011), the use of fake names can help Saudi students in general and women, in particular, to cross the boundaries of and achieve some sort of gratification or release of their emotions while anonymity guarantees them immunity from social censure or parental displeasure (Al-fawaz, 2012).

Despite the belief that people who show increased privacy concerns will reveal little information, Al-Saggaf’s (2011) – as opposed to Al-Otaibi’s – participants commonly disclosed their identity including personal information such as their cell number. By revealing their cell number, Saudi women were different from western women who are more likely to conceal their personally identifiable information related to physical address or cell phone numbers (Gross & Aqusiti, 2005; Tufekci & Spence, n.d.; Shade, 2008, Young & Hasse, 2009).

One explanation could be that Saudi women showed greater awareness of their privacy settings such as blocking others from seeing their information. Additionally, Saudi women are more likely to reveal information to their friends when they trust them, and the majority of Saudi women have existing offline relationships with their Facebook friends (Al-Saggaf, 2011). As indicated by Pempek et al. (2009), the potential audience for their profiles was identified to affect their information revelation behavior.

This study will add to the literature by examining the privacy concerns and information revelation behavior (amount and accuracy) of Saudi female students in Australia. Given that these students are away from home, the study will examine whether their information revelation behavior differs from their counterparts in Saudi Arabia or whether their culture remains a strong influence despite the geographical distance.

Positive and Negative Impacts of Facebook Usage

Al-Otaibi (2011) found that the positive effects identified by his participants outnumber the negative ones. Among the various positive effects of Facebook, the participants mentioned that the site helps them strengthen their social cohesion, create freedom of self-expression, and enhance educational attainment (Al-Otaibi, 2011). Other common positive effects were an increase in the person’s self-esteem and social capital (Ellison et al, 2007).

Additionally, intensive use of Facebook can increase the users’ civic and political engagements (Valenzuela et al., 2009). This benefit was expressed by Saudi women (Al-Saggaf, 2011) who found Facebook as an avenue from which they can engage with each other in some serious discussions such as public affairs, for instance, women’s right to drive cars in Saudi Arabia.

On the other hand, Facebook users reported several negative effects. The majority of Facebook users, regardless of their gender or culture, found a major disadvantage to being the amount of time they spent on Facebook (Al-Otaibi, 2011; Al-Saggaf, 2011, Young, 2009; Shade, 2008), which sometimes resulted in neglecting their families and studies (Al-Saggaf, 2011) or psychological isolation (Al-Otaibi, 2011). In contrast to western students who belong to an individualistic culture (Kim, et al. 2011), Saudi students belong to a collectivistic culture characterized by family commitment (Oshan, 2007).

As such, Saudis are expected to keep in touch with their family by visiting them and spending as much time as they can with them (Al-Saggaf, 2004). As a result of these cultural differences, Saudi students reported that the time they spent on Facebook detracted from the time these individuals spent with their families (Al-Saggaf, 2011). Al-Otaibi’s (2011) participants reported that Facebook could violate the Saudi Arabian social norms or traditions.

Some Facebook users admitted that they became Facebook addicts which negatively affected their academic lives (Al-Saggaf, 2011). In terms of the effect of Facebook use on academic achievements, Kirschner and Karpinski (2010) and Pempek et al. (2009) found a significant negative relationship between Facebook use and academic performance. This was emphasized by Al-Saggaf’s (2011) participants who admitted that they became Facebook addicts which negatively affected their academic lives (Al-Saggaf, 2011). Ellison et al. (2007), on the other hand, found no relationship between low grades and the use of Facebook.

This study will also add to the literature by identifying the positive and negative effects of using FB on Saudi female students studying in Australia. Are the positive effects more than the negative effects or vice versa? Specifically, the study will examine the effects of FB on the students’ social lives, time management, and academics.

Research Gap

Based on the reviewed literature, it has been found that all of the research has been done either on college students from developed countries or on Saudi students who study in Saudi Arabia and no research has been done to investigate the use of SNSs by international Saudi women in Australia. It could be argued that Saudi female students in Australia may have different experiences than their counterparts in Saudi Arabia due to the immediate exposure to such technologies as well as being away from some of the Saudi cultural issues – this is a key issue in the current research will address.

The current research aims to fill the literature gap and examine the international Saudi women’s use of SNSs which are to some extent used in most of the Australian universities as part of their strategies to enhance the students’ educational experience. Additionally, the current research aims to understand the cultural constraints Saudi females face in their Facebook use, even in the west. Female Saudi students using Facebook in Australia are a complex group; they are from a gender-segregated society using an international communication tool in a liberal society. This research will investigate the use of Facebook by women from culturally conservative Saudi Arabia in the west and will try to understand how their use of the SNS differs from their use in Saudi Arabia and by their western counterparts. The study will examine the phenomenon by employing lenses from the proposed Technology Appropriation Model.

Whereas the motivators for using Facebook have been extensively studied, only one study (Aljasir et al., 2012) bothered to look at the reasons why Saudi students may not use Facebook. This study will add to this literature by also looking at some of the reasons why international Saudi female students may be discouraged from using FB.

Moreover, the studies reviewed above are limited in the sense that those that used college students as participants only focused on undergraduate students. This study will deviate from this norm by using both undergraduate and graduate students. It is also the expectation of the researcher that differences in demographic factors may have an effect on the motivation for and use of Facebook among Saudi female students studying abroad. Taking into consideration all these factors would help to address the research questions particularly in the context of the Saudi cultural values, beliefs, and practices.

Theoretical Model

A review of the SNSs literature revealed that the majority of the studies, which concentrate on the examination of the motives to use SNSs by college students, were conducted using the Gratifications and Uses theory (Joinson, 2008; Pempek et al, 2009; Kim et al, 2011; Al-Otaibi, 2011; Raacke & Bonds-Raacke, 2008). However, understanding the motives to use the site would not be enough as students’ uses and experiences change over time (Lampe et al., 2008), and what has been considered

initially when they adopt the technology as appropriate may change over time to be disappropriated (Caroll et al., 2002). Consequently, the current study will use the Technology Appropriation Model which allows the researchers to identify not only the various motives that may initially attract the students to use SNSs but also how the students shape and adapt SNSs to meet their needs through the appropriation process which can result into their daily integration of the site. The reason for using the TAM, therefore, is to narrow the literature gap that exists in the utilization of this model to understand technology appropriation among different groups. Moreover, using the TAM will provide more information by going beyond the “why” of technology appropriation and addressing the “how” as well.

The use of TAM would help the researcher to identify the factors that draw international Saudi female students to Facebook, what factors may discourage them from using the site, the reasons as to why they use FB, and how their use of FB evolves and circumstances. The following diagram represents the Technology Appropriation Model, which identifies three sets of factors that influence the use of any technology.

Methodology

This chapter provides an overview of the methods employed to investigate the use of Social networking sites (SNSs) by Saudi female students in Australia. First, justification for the use of a qualitative approach is discussed. Then, a comprehensive description of the data collection method is provided.

Research Approach

Based on Neuman’s (2006) classification of research, the current research should be considered an exploratory study because it is designed to investigate the use of SNSs in a context that has not been heavily investigated (i.e., international Saudi female students use of and attitude towards SNSs). It is also descriptive since the study attempts to describe “how” international Saudi female students in Australia use SNSs and whether there is any difference between their experiences when they were in their home country (i.e., Saudi Arabia) and abroad. Consequently, to achieve the study’s objectives and answer the research questions, this study’s approach was qualitative and utilized in-depth interviews to collect information (Neuman, 2006).

By adopting the in-depth interview methodology, the researchers would be able to gain insight into the feelings, beliefs, and thoughts of the participants. This approach also allows the researchers to deeply examine the phenomenon in its natural settings and through the inter-subjective meanings expressed by the participants under investigation; such meanings are formed through interaction with others and through historical and cultural norms that operate within their lives (Creswell, 2007).

Data Collection Method

To obtain rich data on the Facebook use of Saudi female students in Australia, this study is framed based on the interpretive (i.e., constructive) paradigm tradition. The interpretive paradigm, which is the basis for our study, is concerned with understanding the phenomenon (i.e., FB use in this case) from the perception of the participants under investigation and through the use of the qualitative methods, such as interviews and observations, which is assumed to help the researchers understand the phenomenon in details (Neuman, 2006). Consequently, this study involved five semi-structured individuals in-depth interviews, all of which were held in Melbourne.

The interviews were made up of open-ended questions designed to provide respondents with an opportunity to express their opinions about the phenomenon under investigation. The interview questions were designed to get participants to share a variety of information relevant to the thesis. The questions ranged from general questions on the students’ experience with SNSs to more in-depth questions related to their use of and motives to use Facebook in particular. Issues discussed in the interviews include their current use of SNSs; when, why, and where they started using these sites with a focus on FB; their attitudes toward and perceptions of these sites; the positive and negative effects of their FB use; and any changes in their use of Facebook in Saudi Arabia versus in Australia. The interviews also concentrated on privacy or security concerns and awareness.

Sample

Given the nature of the current study which requires an in-depth discussion as well as the time limit to conduct the study, data were collected only from five Saudi female students who are currently pursuing their high education degrees at different universities in Melbourne and were willing to voluntarily participate in the study. Participants were recruited based on having an account on Facebook or any other SNSs. The demographic information about the participants is cataloged in the following table:

Table 4: Demographic Information of Participants in the Study.

In fact, given the small sample size, collecting data from a wide variety of backgrounds was important to ensure a range of different opinions. Consequently, as seen in the table, respondents were recruited to be from varying age groups, marital status, areas of study, and native regions in order to collect opinions that will most likely reflect the larger population. Students come from either the socially conservative Riyadh province or the more liberal Makkah province and may thus have different attitudes or experiences towards the use of SNSs. However, it is crucial to note that all of the study’s single interviewees were natives of the Makkah province because the researcher found it very difficult to find single participants from Riyadh.

This difficulty in finding single females from Riyadh could be related to the more restrictions facing females in terms of studying overseas as compared to their counterparts who come from Makkah province. In fact, the Makkah province is considered to be one of the most multicultural and diverse cities in the Muslim world due to the millions of Muslims who visit the sacred city of Makkah(i.e., also known as Mecca, the capital city of Makkah province) every year. Some of these pilgrims come from diverse cultural backgrounds, such as Asian and European who then migrated and settled in the province. Consequently, despite the undeniable fact that Saudi culture and traditions are applied in all families in Saudi society, the level of restrictions imposed by Saudi families on their daughter may differ based on the region to which they belong.

Data Collection Procedure

Upon getting approval from the ethics committee to conduct the study, invitation emails were sent to a number of Saudi females who were among the researcher’s personal contact and are believed to have the ability to contribute to the current study(i.e., they were chosen based on a purposive sampling strategy (Neuman, 2006)). The email provided the participants with a brief description of the nature and aim of the study (i.e., a pilot study intended to examine the use of SNSs by Saudi women in Australia). The participants were given the freedom to choose a time and place suitable for the interview. After few weeks, was able to gain consent for participation from only 5 of the invited students.

Upon arriving at the meeting avenue, the participants were given a plain language statement that described the participants’ confidentiality, anonymity, and their rights, such as their right not to answer a question or to stop the interview or leave at any time they wished.

They were also asked to sign a consent form. Once the potential interviewees signed the informed consent form, all participants were asked to answer a one page questionnaire that ascertained their demographic characteristics including age, educational level, native region in Saudi Arabia, and whether they had heard about SNSs. After that, all participants were asked to answer a number of audio-taped semi-structured questions in order to give them the chance to freely discuss the questions they were asked. Each one-on-one interview was intended to last between 45 to 60 minutes.

However, some of the interviews took more than 60 minutes due to the time spent on translating some of the questions for the participants who didn’t speak English well. Even though all of the participants are bilingual students, some of them still have difficulty with the English language and found it difficult to deeply express their experiences in English. Consequently, they were allowed to describe their experiences in their own language (i.e., Arabic) in order to allow them to provide a detailed and clear explanation and description of their experiences.

Data Analysis

Following each interview, the recordings were transcribed word-for-word from the audio tape and translated when required. After that, the transcripts were sent back to the interviewees to make sure that the transcribed answers represent exactly what they intended to say. Then, the transcribed data were analyzed and coded using the content analysis approach. The process of coding the transcribed data consisted of three phases: open, axial, and selective and was guided by the concepts from the Technology Appropriation Model (TAM) in order to gain a deep insight into the adoption and appropriation of SNSs among Saudi female students.

In the coding process, the researchers looked for words or phrases that referred to the concepts or themes represented in the Technology Appropriation Model. Each time a new theme was discovered, it was given a code and category labels. For each theme, we assigned an abbreviated code of a one-to three-word label based on a template provided by Neuman (2006).

The results had more than 30 codes or themes. After that, the number of the themes was reduced by grouping all interrelated themes into one core category or theme. For example, themes such as ease of use, features, familiarity, and expected usefulness were identified and grouped together in one main theme called “Attractors.” At the end of the coding process, we were able to identify the following themes: attractors (A), appropriation criteria (APC) and Reinforces (R), all of which were derived from the technology appropriation model (Carroll et al., 2002).

The analysis of these themes helped us to examine whether the students identified Facebook as an appropriated technology. In addition, another core theme was also identified and coded as Facebook Use (FU), which includes other sub-divided themes, such as Time Commitment, Facebook Purposes, Facebook Activities, and Facebook Privacy. Each of these subdivided themes consists also of other related themes identified in the initial stage of coding. Such themes help us to understand the way Saudi female students use and experience FB. Following the analysis of the data, the results were compared to both anticipated findings and statistics from other studies in the literature in order to find commonalities and distinctiveness in the data.

References

Acquisti, A., & Gross, R. (2006). Imagined Communities: Awareness, Information Sharing, and Privacy on the facebook. 1-22.

Al-Fawaz , N. (2012) Facebook profiles reveal young women’s obsession to post pictures of body parts. Web.

Al Hazmi, A., & Nyland, B. (2011). Saudi International Students in Australia and Intercultural Engagement: A Study of Transitioning From a Gender Segregated Culture to a Mixed Gender Environment. ISANA International Education Association Inc.

Aljasir, S., A. Woodcock, et al. (2012). Facebook Non-users in Saudi Arabia: Why Do Some Saudi College Students Not Use Facebook? International Conference on Management, Applied and Social Sciences. Dubai.

Al-Kahtani, N.K., Ryan, J. C., & Jefferson, T, I. (2006). How Saudi female Faculty Perceive Internet Technology usage and Potential. Information Knowledge Systems Management, 5, 227-243.

Al-Otaibi, A. (2010). Digital Divide in Saudi Arabia: Inequality of Usage. Working Paper (September, 2010: MSC, information Systems: University of Sheffield), 1-85.

Alqarni, I. (2011). Middle East Students Studying in Australia- The Saudi Arabian Students’ Example. Canberra, Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission.

Al-Saggaf, Y. (2004). “The effect of online community on offline community in Saudi Arabia.” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 16(0).

Al-Saggaf, Y. (2011). Saudi Females on Facebook: An Ethnographic Study. International Journal of Emerging Technologies and society.

Australian Education International. (2011). Research snapshot: international student numbers. Web.

Carrol, J. Howard, S. Peck, J. & Murphy, J., 2003. From adoption to use: The process of appropriating a mobile phone. AJIS, 10(2), pp. 38-48.

Carrol, J. Howard, S. Vetere, F. Peck, J. & Murphy, J., 2001. Identity, power and fragmentation in cyberspace: Technology appropriation by young people. AISeL, pp. 1-9.

Carrol, J. Howard, S. Vetere, F. Peck, J. & Murphy, J., 2002. Just what do the youth of today want? Technology appropriation by young people. IEEE, pp. 1-9.

CRESWELL, J. W. (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches, Sage Publications, Inc.

Dwyer, C., Hiltz, S., & Passerini, K. (2007). Trust and Privacy Concern within Social Networking Sites: A Comparison of Facebook and MySpace. Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS): Proceedings, 1-13.

Ellison, N. B., & Steinfield, et al. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143-1168.

Fallon, F., & Bycroft, D. (2009). Developing Materials for Homestays and Students from Saudi Arabia. Paper presented at the ISANA international education association 20 th international conference. Web.

Gray, K., S., & Chang, et al. (2010). Use of social web technologies by international and domestic undergraduate students: implications for internationalising learning and teaching in Australian universities. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 19(1), 31-46.

Hargittai, E. (2007). “Whose space? Differences among users and non‐users of social network sites.” Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication 13(1): 276-297.

Joinson, A. (2008). ‘Looking at’, ‘Looking up’ or ‘Keeping up with’ People? Motives and Uses of Facebook. Proceedings • Online Social Networks: CHI 2008, 1027-1036.

Jones, H. and H. Soltren (2005). “Facebook: Threats to privacy.” Social Science Research: 1-76.

Kennedy, G., B. Dalgarno, et al. (2007). The net generation are not big users of Web 2.0 technologies: Preliminary findings.

Kennedy, G. E., & Judd, T. S. (2010). Beyond Google and The “Satisficing” Searching Of Digital Natives. n.a: 119.

Kim, Y., Sohn, D., & Choi, S. M. (2010). Cultural Differences in Motivations for Using social network Sites: A Comparative Study of American and Korean College Students. Journal of Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 365-372.

Kirschner, P.A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook and Academic Performance. Working Paper: Centre for Learning Sciences and Technologies (CELSTEC), 1-39.

Lampe, C., Ellison, N., & Steinfield, C. (2006). A Face(book) in the Crowd: Social Searching vs. Social Browsing. Conference paper: ACM 1-58113-000-0/00/0004. 1-4.

Lampe, C. A. C., N. Ellison, et al. (2007). A familiar face (book): profile elements as signals in an online social network, ACM.

Lampe, C., Ellison, N., & Steinfield, C. (2008). Changes in Use and perception of Facebook. CSCW journal, 721-730.

Midgley, W. (2009). When we are at Uni our minds are at home: Saudi students worrying about wives. Paper presented at the ISANA international education association 20 th international conference. Web.

Ministry of Higher Education (2010). King Abdullah Scholarship Program to continue for five years to come. Ministry Deputy for Scholarship Affairs in a statement. Web.

Muscanell, N. and R. Guadagno (2012). “Make new friends or keep the old: Gender and personality differences in social networking use.” Computers in Human Behavior 28: 107-112.

Neuman, LW 2006, Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, Pearson Education, University of Wisconsin, Whitewater.

Oshan, M. (2007). Saudi women and the internet: gender and culture issues. Loughborough UniversityDoctor of Philosophy 403.

Pempek, T. A., Yermolayeva, Y. A., & Calvert, S. (2009). College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 227–238.

Scholarship,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13, (1), 210-230.

Shade, L. R. (2008). Internet Social Networking in Young Women’s Everyday Lives: Some Insights from Focus Groups. Our Schools, Our Selves, 17, 65-73.

Shaheen, A. (2010). “Facebook draws Saudi women fans“. Gulf News. Web.

Shaw, D. (2009). Bridging differences: Saudi Arabian students reflect on their educational experiences and share success strategies.

Tufekci, Z. & Spence, K. Social Network Sites: A gendered Inflection Point in The Increasingly Web? American Sociological Association.

Valenzuela, S., Park, N,. & Kee, K. F. (2009). Is there Social Capital in a Social Network Site?: Facebook Use and College Students’ life Satisfaction, Trust and Participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14, 875-901.

Young, K. (2009). “Online social networking: An Australian perspective.” International Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society 7(1): 39–57.