An oligopoly is a kind of market structure wherein a few sellers (oligopolists) control the proceedings in an industry or a certain market segment. The term is derived from the Greek word oligo meaning ‘few’ and the word opoly is like in monopoly or duopoly. Since there are only a few economic players in such a market structure, each oligopolist usually pays a great deal of careful attention to the activities of the other market participants. The tactical decisions of a certain company influence, and also get influenced by, the actions of other oligopolists (Luo & Seung, pp. 141-155). The strategic planning processes carried out by various companies in such a market scenario always entail taking into consideration the possible rejoinders of the other key market players. Consequently, oligopolistic economies or market segments are always considered to possess inherent high-risk probabilities for collusion (Vandenbosch and Weinberg, pp. 224-249).

The instantiation of an oligopolistic market structure is a widespread phenomenon. In terms of a quantitative portrayal of an oligopoly, the four-firm concentration ratio is commonly made use of to describe their nature. This assessment denotes the market share of each of the four most dominating companies in a market in terms of a percentage. Competition in an oligopoly can bring about a wide diversity of varied upshots. Under certain circumstances, the market participants may adopt a restrictive trade approach (collusion, market sharing, etc.) to inflate prices and similarly confine production volumes to that occurring in a monopoly. In cases wherein a formal agreement about such collusion exists, a situation which is known as a cartel arises. Nevertheless, a formal agreement need not exist in terms of the collision occurrence (Selmer & de Leon, pp. 321-338). Under different circumstances, competition amongst participants in an oligopolistic economy may be cutthroat, with comparatively low costs and a high rate of production being the market parameters. This may indirectly be advantageous to the markets as such conditions tend to perfect competition. The investigation into the details of product differentiation in oligopolistic markets reveals that extreme levels of differentiation may arise to cope with competitive factors (Pinheiro and Bates, p. 167).

A lot of major strategic choices companies make entail discrete decisions like making a decision about the site for a new business facility, deciding on how to position a particular product in the product space, or on provisos stipulated in a service contract. Such decisions are rather intricate and characteristically involve the deliberation over several demands, price, and other competitive issues. (Cooper, 303-325) Analysis of such discrete choices poses a challenge for the reason that they are either influenced or affect the decisions made by other market players. The evaluation of the nature of oligopolistic businesses is founded on game theory. The companies attempt to predict how their competitors may respond in case they adopt a particular approach about their pricing policy (Verbeek, pp. 45-48).

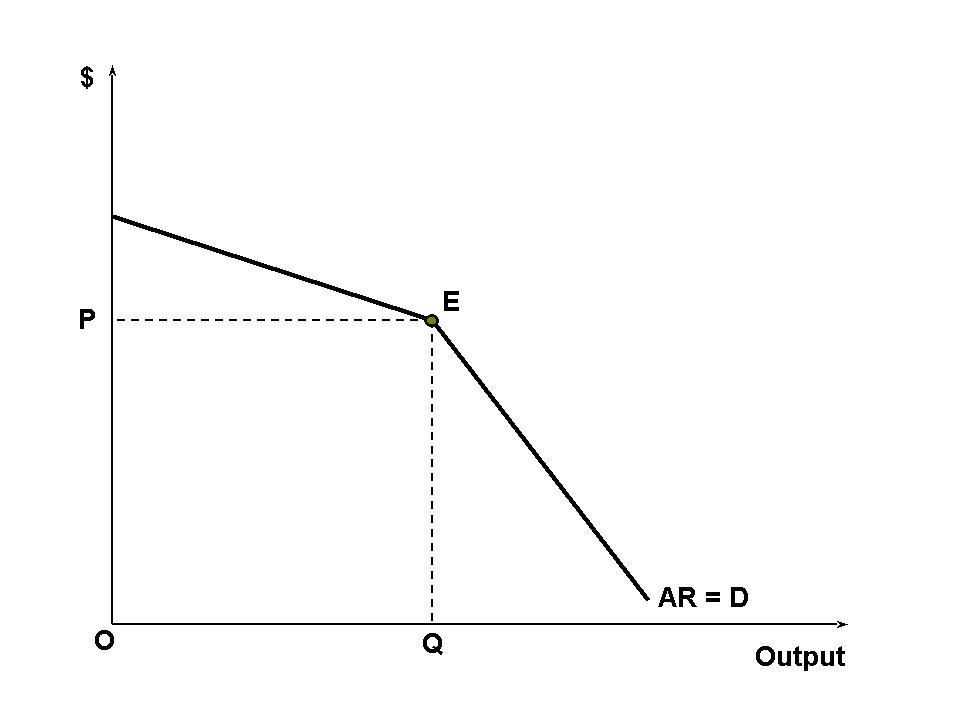

The explanation for the kink in the demand curve is that in an oligopolistic competitive environment, companies are not likely to increase their prices since a price rise would undoubtedly lose them, several consumers, as rivals would normally disregard that price rise to win over a significant market share on account of a relatively lower price offering. Nevertheless, even a hefty price cut is likely to yield only a handful of customers since such a measure would induce a price war with other competitors. Thus, the curve is more elastic in terms of price rises and significantly less in the case of price decreases (Neven and Thisse, p. 127).

As a result of the severe price competitiveness induced by this ‘sticky’ demand curve, companies generally use non-price competition to facilitate the yielding of better revenue figures and greater market share. Such non-price competitive aspects include advertising, greater product differentiation, and brand proliferation (Worthy, pp. 345-350).

In this paper, we choose to analyze Wal-Mart in an oligopolistic environment as it does not operate in a monopolistic arena since other companies exist which are fiercely competing with it for market share and revenues. A monopolistic company usually gains both short-range as well as long-term returns from the market by setting high prices for its offerings. In contrast, Wal-Mart’s pricing strategy makes sure that its price offerings are the most attractive in the markets (Bradley, pp. 49-67). This designates an oligopolistic character of companies such as Wal-Mart which focus on pushing competitors away from the market by setting up a tight competitive environment with trifling gains. With efficient inventory management, compressed wages for the workforce, larger employee strength, and demanding cost cutbacks from suppliers, Wal-Mart makes certain that the average cost is kept as low as possible in comparison to other market rivals (Moorthy, pp. 141-168).

The economic theory of contestable markets sets down an outline that helps one to comprehend the effect of Wal-Mart’s strategy on the economy. The fundamental proposal of this theory suggests that a firm’s decisiveness is largely affected by prospective competition on account of new market entrants as well as existent competition put up by already established market players. The static economic theory of oligopoly markets, suggests that companies decide on price and production volumes in a manner that facilitates the maximization of profits rooted in the anticipated reaction of other market players (Zeithaml, pp. 362-375).

As per static economic models, oligopoly pricing strategies and monopolistic profits may continue without prompting entry. However, according to the economic theory of contestable markets, a company operating in an oligopolistic environment is required to expect that monopolistic yields might trigger the entry of new entities into the market. (Heskett, 78) In case there is a lack of barriers to entry, new players are bound to make an entry into the market provided that monopolistic profits are being yielded in the markets. In the contestable market structure, oligopolistic businesses may enforce two rather different obstacles for the new entrants into the markets (Ramlall, pp. 51-64). A barrier to entry might manifest due to the competitive advantage that already existing companies enjoy as compared to prospective entrants. Simulated barriers to entry might arise if existing companies are capable of employing their political influences to enforce legal or additional noneconomic barriers to entry for new entrants. In addition, they manipulate their pricing and production strategies to interrupt or put off new entries (Summers, pp. 14-19).

There are quite a few potential bases for competitive advantage for existing companies as compared to potential competitors. It may be due to the already incurred and stabilized capital and infrastructural costs. New entrants, in contrast, have to invest in capital equipment in addition to accounting for variable costs on market entry. In addition, already existing firms may draw on their leverage to compress remunerations and hence reduce their labor expenses as compared with significant labor overheads incurred by new entrants that have to provide competitive compensation packages (Slack and Lewis, p. 44).

Multi-brand companies in an oligopoly often seek new beneficial product positioning schemes and experiment with already present brand portfolios repositioning in addition to pricing. An oligopolistic company maximizes the shared profits covering its brand portfolio, and each one of its brands not only contends with the brand lines of other players but also supports (and is supported by) other brand lines belonging to the same firm. Customers generally evaluate products in perceptual terms whereas the companies fabricate them in a physical space. Typically the customer translates correctly weighted physical features into personal perceptual attributes – an issue that drives demand, and expenses. These projected demand and costs deliverables then give rise to a system to recognize product line revenue-maximizing physical positioning and repositioning policies, which explain competitive price responses (Schroeder, pp. 105-117).

A contestable economic markets structure facilitates investigation about numerous divisive issues concerning Wal-Mart’s strategy concerning retailing markets. Till the very recent past, it had been complicated to investigate such issues thoroughly due to the composite character of the competitive contestable markets. Nevertheless, the latest research techniques have been successful in analyzing the dynamic relations shared by Wal-Mart and other players, not only in the retailing context but also in the general economic scenario (Schmidt, p. 78).

To comprehend how a solitary company like Wal-Mart affects the economy, one has to resort to a counterfactual hypothesis. In this case, the hypothesis looks into a scenario where the economy might have operated devoid of any contribution of the firm over a particular time. This framework must subsequently account for the dynamic modifications that might have been triggered by companies in the nonexistence of Wal-Mart. In this paper, we extensively refer to the Global Insight study which made use of the aforementioned hypothesis and employed a general equilibrium framework to model how the U.S. economy might have operated in case Wal-Mart was nonexistent during the period ranging from 1985 to 2004. This initiative also takes account of the dynamic modifications that might have ensued in retailing as well as in the general economic context. The influence of Wal-Mart is implicated through alterations in national productivity, product prices, remunerations, customer purchasing capability, employment rates, and inflation-attuned earning levels (González-Benito, pp. 87-102).

An explanation/assessment of the real-world strategy

A. Wal-Mart’s Market Share of the Retailing Industry

Undoubtedly, Wal-Mart has undergone a rapid development and growth phase, gaining a significant share of the retailing markets based in the United States. The Wal-Mart division controls large-scaled supermarket procedures across the nation, boasting of a market share of a staggering 20% in the supermarket sector worth $479 billion. Wal-Mart has in addition expanded insistently to penetrate overseas retailing markets as well. Latest joint venture initiatives and takeovers in countries like Brazil, Japan, Central America, U.K, and other key countries have helped Wal-Mart emerge as a key market entity in overseas and domestic markets alike (Bissell, p. 335).

B. Price Competition

The findings of The Global Insight research initiative pointed out that the speedy growth of Wal-Mart in the retailing sector was principally the consequence of fierce price competition. Several prior types of research have documented that the firm drastically cut down consumer prices, and the Global Insight study corroborated these assertions.

The effect of Wal-Mart over the duration ranging from 1985 to 2004 was a cumulative drop of 9.1% in terms of food-at-home prices, a 4.2% drop in prices of commodities and goods, and a 3.1% fall in consumer prices on the whole as computed by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Wal-Mart was successful in assertively cut back on prices on account of dynamic competition. The dynamic competition was triggered using high scaled capital investment in product distribution and inventory management expenses, reduced importation prices, and superior productivity of supply chain activities (Shaked and Sutton, pp. 3-13).

In addition to cost savings on account of capital investments and reduced importation costs, further residual cost savings due to Wal-Mart’s influence on total factor output needs to be mentioned. This rise in total factor productivity is consequential of enhanced technological and prolific approaches of the firm (Carl & Hal, p. 229).

In the context of contestability in the retailing sector, it was a possibility that already existent firms had a significant competitive advantage concerning Wal-Mart’s position in retail sectors during the initial phases of this duration. Nevertheless, the barriers to entry that might have arisen for Wal-Mart were crumpled due to the dynamic competition presented by Wal-Mart. In light of the prevalent market position of Wal-Mart, it might be argued that Wal-Mart has of late acquired a status wherein it can exercise such market leverage to holdup or put off new entry to the markets. However, in that case, Wal-Mart’s influence in cutting down market prices would have been less dynamic since its market share grew over some time. It has been documented that Wal-Mart played a principal part in price falls all through the aforementioned period (Tirole, p. 28).

C. Wage Compression

In light of the prevailing status of Wal-Mart in the retailing sector, it may also be argued that Wal-Mart is capable of utilizing the market influence to compress wages. Wage compression might lead to lower labor expenses for Wal-Mart as compared to rivals in retailing. Analysis of a significantly sized sample of Wal-Mart data for workforce wages categorized by organizational position and site in comparison to the remuneration data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) revealed that there is practically no substantiation of Wal-Mart paying notably lower wages and their remuneration structure is proportionate with retail sector averages for the employees analyzed.

However, there is a certain section of workers in the retail markets that receive salaries appreciably higher than the compensation paid to other Wal-Mart recruits. This employees section, grocery personnel operating under a union in major cities, has earnings that are 20–40% higher than similar groups of employees working in Wal-Mart. However, the higher salaries for unionized employees translate into inflated prices in those grocery sections (Bresnahan, pp. 457-482).

D. Profit Rates

If Wal-Mart used its market influence to a setback or prevent new market entry and increased competition, this would be reflected in superior profit records. As per various statistical data, over the aforementioned time duration Wal-Mart underwent speedy growth in terms of sales and overall income; yet, profit margins on sales have continued to hover around the 3.32–3.59% mark.

As per the contestable markets economic theory, the market authority would be manifested in the form of profit rates that are superior to the industry averages. When the profit rates of Wal-Mart are compared with other businesses in the retailing sector the data reveals that the firm’s profit rates are very much similar to that of its market rivals. As compared with its closest challenger, Costco, Wal-Mart’s revenues per share are a little lower, whilst yield rates are comparatively better. Factors like return on equity and pre-tax margin rates are appreciably higher than that of other market players (Greene, p. 256).

Once a retailing firm achieves a predominant authority in the market, it starts manipulating a major part of the yields of a lot of its suppliers. Consequently, such firms can at times use more control in terms of products positioning and brand image than even the producer. (Werther & David Chandler, p. 332). In an oligopoly firms try to take advantage of economies of scale. Big retailers reduce costs by acquiring larger quantities at once. They market and distribute these articles resourcefully to numerous strategically placed outlets and stores to optimize transportation and other overheads. Pure magnitude symbolizes the single largest resource lead which market giants like Wal-Mart have (Miguel, pp. 311-321). Utilizing scale economies, large retailers usually set prices that cannot be contended with by petite competitors. Thus, most undersized competitors find it hard to cope with large retailers solely on price in an oligopoly (Kotler, p. 276). Typically, large retailers deal with a wide range of products. Putting up varied products for sales significantly amplifies store traffic. However, product lines for general commodity retailers like Wal-Mart are not as diversified as compared to their specialized competitors. In the case of general commodity retailers, only those products that exhibit substantial sales volume are carried forward, inducing greater levels of economies of scale (Doraszelski and Draganska, pp. 125-149).

Wal-Mart’s influence and authority are directly and broadly acknowledged in the oligopolistic markets. With its sheer size and capital resources, Wal-Mart can continue to run even an under-performing outlet in the long term while entering a new region. Efficient distribution strategies and greater supply chain productivity allow the firm to set remarkably low price offerings that are too tough for competitors to contend with (Elsdon, pp. 39-47). Its comparatively wide product range–particularly in superstores wherein both groceries and general goods are made available–creates substantially large store traffic and enables a convenient shopping experience for the customers. In addition, its cost-control-oriented organizational approach, which incorporates a dependency on economical, part-time labor strategy, keeps costs lows are allowed the firm to position its products accordingly (Gabszewicz and Thisse, pp. 340-359).

Works Cited

- Bissell, B, Resistance Change, Auckland: Ebsco publishing, 2006.

- Bradley, Thomas L. ‘Cultural dimensions of China: Implications for international companies in a changing economy’. Thunderbird International Business Review 41.1, (2006): 49-67

- Bresnahan, T.F. “Competition and collusion in the American automobile industry: the 1955 price war”. Journal of Industrial Economics 35.4 (2004): 457-482.

- Carl Shapiro, Hal R. Varian. Information rules: a strategic guide to the network economy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1998.

- Cooper, Danielle. ‘Understanding multinational organizations in China’. Journal of Organizational Behavior 28.3 (2007): 303-325

- Doraszelski, U. and Draganska, M. “Market segmentation strategies of multiproduct firms”. The Journal of Industrial Economics 54.2 (2008): 125-149.

- Elsdon, R. “Creating Value and Enhancing Retention through Market Development: The Sun Microsystems Experience”. Human Resource Planning. 22.2(2004):39-47.

- Gabszewicz, J.J. and Thisse, J.-F. “Price competition, quality and income disparities”. Journal of Economic Theory 20.3 (2006): 340-359.

- González-Benito, J. “A review of determinant factors of motivation proactivity” Business Strategy and the Environment 15.2 (2007): 87-102.

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis. (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003.

- Heskett, Jack. Market Design: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning and Control. NJ, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1984.

- Luo, Yadong & Seung Ho Park. ‘Strategic alignment and performance of market-seeking MNCs in China’. Strategic Management Journal 22.2 (2006): 141-155

- Miguel, Cunha. “Ecocentric management: an update.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 15.6, (2007): 311-321.

- Moorthy, K.S. “Product and price competition in a duopoly”. Marketing Science 7.2 (2001): 141-168.

- Neven, D. and Thisse, J.F., On quality and variety competition. In: Gabszewicz, J.J., Richard, J.-F., Wolsey, L.A. (Eds.), Economic Decision Making: Games, Econometrics and Optimization. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 2005.

- Pinheiro, J. and Bates, D. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-Plus. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2000.

- Ramlall, S.J. “Measuring Human Resource Management’s Effectiveness in Improving Performance”. Human Resource Planning. 26(2006):51-64.

- Schroeder, Roger G. “A resource-based view of manufacturing strategy and the relationship to manufacturing performance”. Strategic Management Journal 23.2 (2002): 105-117.

- Selmer, Jan & Corinna de Leon. ‘China: Organizational acculturation in foreign subsidiaries’. The International Executive 35.4 (2004): 321-338

- Slack, Nigel, and Michael Lewis. Operations Management: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Summers, S.B. “Strategic Skills Analysis for Selection and Development”. Human Resource Planning. 20.3(2003): 14-19.

- Schmidt, S.J. Econometrics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

- Shaked, A. and Sutton, J. “Relaxing price competition through product differentiation”. Review of Economic Studies 49.1 (2006): 3-13.

- Tirole, J., The Theory of Industrial Organization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

- Vandenbosch, M.B. and Weinberg, C.B. “Product and price competition in a two-dimensional vertical differentiation model”. Marketing Science14.2 (2007): 224-249.

- Verbeek, M. A Guide to Modern Econometrics. (2nd ed.). NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2004.

- Wauthy, X. “Quality choice in models of vertical differentiation”. Journal of Industrial Economics 44.3 (2007): 345-353.

- Werther, William B & David Chandler; 2006; Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders. New York: SAGE, 2006.

- Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A. and Malhotra, A. “Service quality delivery through Web sites: a critical review of extant knowledge”. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30.4 (2004): 362-375.